Statues are falling, conversations are changing. We’re in the middle of a much anticipated cultural revolution and it’s becoming clear that our perception of the world is beyond faulty. Amid those changes, even the ostensibly progressive creative industries are finally recognising their roles in building a flawed system. The Grammys have finally renamed their ‘Urban Contemporary’ category in an attempt to stop the racial profiling of artists, and even Anna Wintour herself has apologised for the lack of support she has given to Black voices over her 32-year tenure at Vogue.

In place of London Fashion Week Men’s, which was supposed to take place this past weekend, the British Fashion Council organised a three-day digital residency programme which saw designers being given a timeslot to showcase their creative output. Some hosted panel discussions, others streamed films, VR presentations and even live gigs. Keeping the conversation relevant to what’s happening in the real world, many responded to the Black Lives Matter movement, with the BFC’s own programming for #LFWReset focused on amplifying BAME voices.

These are all important gestures of support to creatives that have so often been overlooked, but the obvious question is — what about those that have already fallen victim to a corrupt system? Just like in general educational curricula, the presence of Black folk in fashion literature is sparse and ambiguous, to say the least. “At the Royal College of Art, when we had a brief introduction to the history of fashion, Black designers’ contributions to history were never really mentioned,” remembers Saul Nash, the Hackney-born designer and dancer, and current Fashion East recipient.

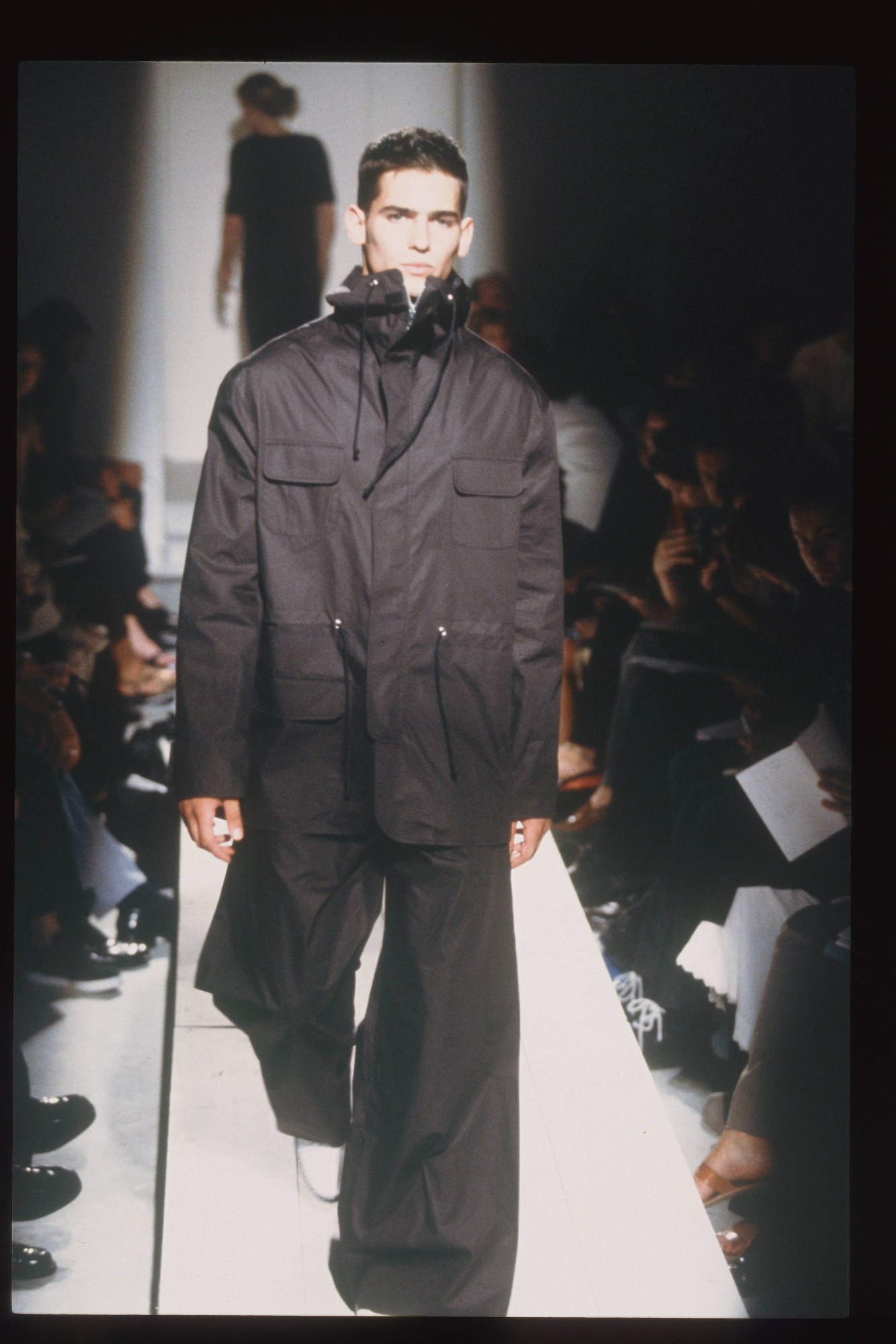

One name that may not have made it onto RCA’s fashion history reading list, but has played a definitive role in establishing London as a major fashion capital is Joe Casely-Hayford. Born in Kent in 1956 into a line of influential Ghanaian creative polymaths, Joe was one of the first Black British fashion designers to attain mainstream success. After graduating from Saint Martin’s School of Art in 1979, he started his career in the early 80s by upcycling surplus military tents into garments, before teaming up with his wife Maria to launch a namesake brand which originally specialised in shirting. His work in both menswear and womenswear earned him multiple nominations at the British Fashion Awards, as well as a broad fanbase that included everyone from Princess Diana to Lou Reed. “A lot of people had the issue that they couldn’t pigeon-hole him, everyone was always quite quick to make assumptions because of the colour of his skin. But his breadth of talent, which extended in so many different ways, made it impossible to define him as just one thing,” explains Charlie Casely-Hayford, Joe’s son who took over their joint business upon his father’s passing in 2019.

Joe was the first-ever designer to design a capsule collection for Topshop back in 1995, and was involved in a whole range of creative ventures including the design of The Barbican’s seminal exhibition on the art of African textiles that same year. A decade later, he became the creative director of the heritage Savile Row tailoring brand Gieves & Hawkes, and in 2009, joined arms with his stylist-designer-model son to launch Casely-Hayford. This new brand brought together Joe’s decades of experience and trailblazing with Charlie’s new perspective, creating a cross-generational approach to a refined wardrobe. “Our collections were an extension of conversations we’ve been having for years, and that’s how we would always design,” says Charlie, whose parents never really encouraged him to work in fashion. “A large part of that was down to the struggles that he had in the industry, he didn’t want his kids to go through the same thing. Still, both my sister [Alice Casely-Hayford, Net-A-Porter & Porter Magazine Content Director] and I ended up in fashion.”

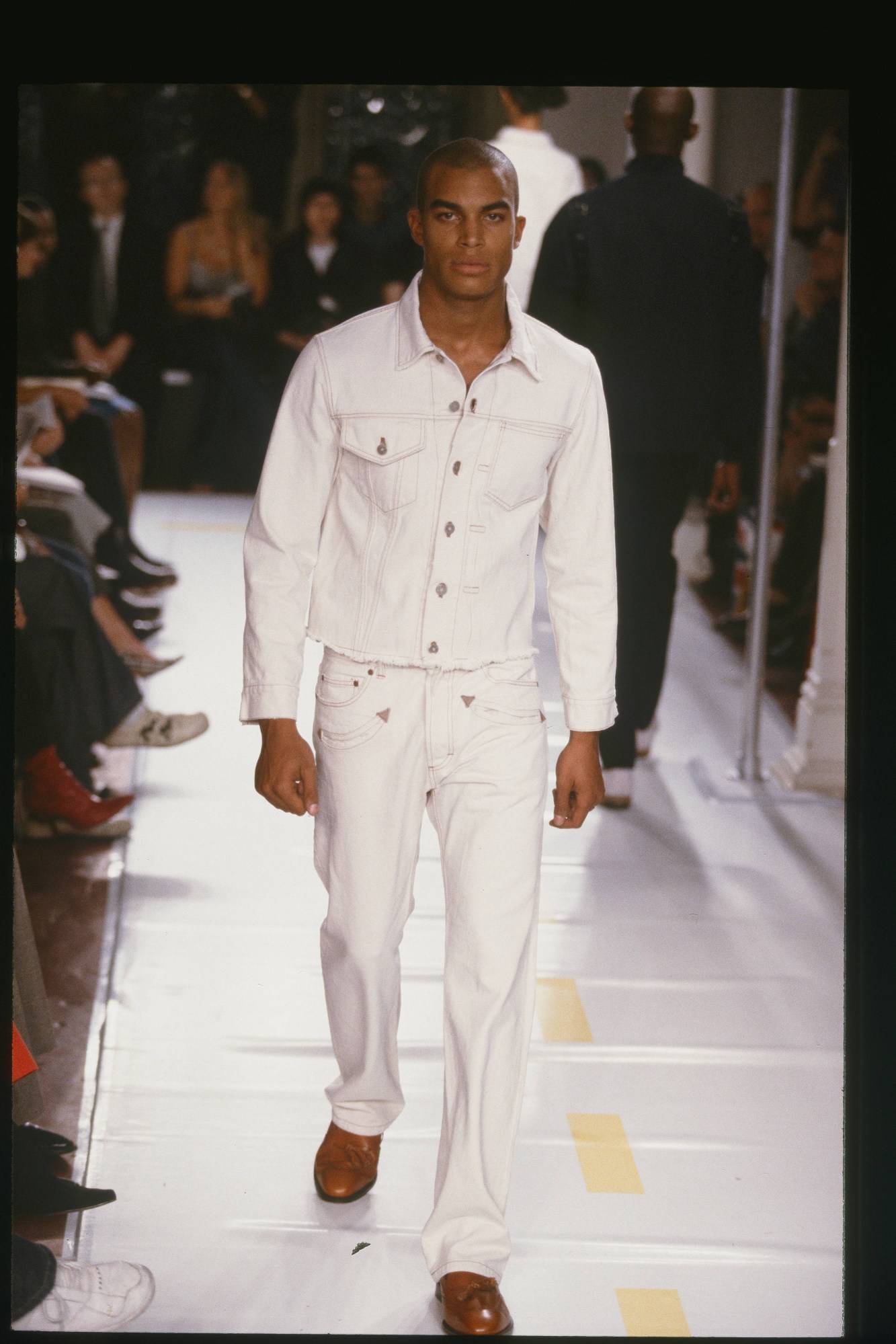

When Louis Vuitton first announced Virgil Abloh as its menswear artistic director, he became the first African-American man to head an LVMH-backed brand. Last year, Rihanna was named the Black woman to launch her own brand with the support of the French conglomerate. But before Virgil and Riri, there was Ozwald Boateng. Appointed as the artistic director of Givenchy’s men’s division in 2003, the London-native self-taught designer of Ghanaian descent became the first-ever Black person to head the design team of a French Maison. His appointment didn’t come out of nowhere, though — for two decades beforehand, Ozwald has steadily built a tailoring empire with his signature vivid colours and decorative fabrics, often paying homage to his heritage by elevating classic tailoring with elements of traditional dress.

He created bespoke costumes for some legendary films and TV show — including some of those outrageous suits Carrie’s BFF Stanford Blatch wore on Sex and The City. Ozwald was a fixture of 00s zeitgeist, but just as he was preparing to take over America, the atmosphere shifted. His vibrant hues and boxy cuts went out of style, swapped out for the outré sex-appeal of exposed chests and slim-fit shirts. The industry quickly forgot about all the barriers he broke. Business declined, global stores were closed, and magazines and newspapers decided to exchange the figure of a confident party boy for an arrogant, out-of-touch man. The Guardian gave his self-produced documentary, A Man’s Story, one star, while GQ put him top of their 2014 Worst Dressed list. That’s nine places above Nigel Farage. Long before the overflowing of kindness, the industry’s message was clear – [read in Heidi Klum’s voice] – one day you’re in and the next day you’re out.

While he may have been absent from recent fashion week schedules, Ozwald’s influence is everywhere. He remains the only Black-owned business on Savile Row, and last year, he hosted a show in New York’s Apollo Theatre in honour of the 100th Anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance.

Indeed, a key issue in the industry remains the lack of a visible presence of Back folk in both business and creative positions in the industry, showing the next generation they too can one day take the helm. This has, however, slowly changed in recent years, as designers like Martine Rose, Nicholas Daley, Wales Bonner and Samuel Ross have picked up the torch and run full-speed ahead into creating successful businesses.

A South Londoner with her HQ in Tottenham, Martine launched her much-loved eponymous label in 2009 and has regularly collaborated with brands like Napapijri and Nike. Over the past decade, she has been a defining figure in developing what some might define as ‘streetwear’ but is in fact just a resolutely contemporary take on ready-to-wear. Proving her influence beyond her own brand, Martine became a menswear consultant for Balenciaga when Demna Gvasalia took over the creative direction, a stint she recently finished after three years.

While the consultant role is one that has increasingly been offered to Black figures in fashion – whether as collaborative artists or members of diversity panels – rarely have they been offered the most lucrative roles.

Dior’s Resort 2020 show in Morocco came under plenty of criticism when they revealed its theme to be “common ground,” presenting ‘luxury interpretations’ of elements of traditional garments from across the African continent. To justify the move, Maria Grazia Chiuri surrounded herself with collaborators who had authority on the subject, including anthropologists, African artists and textile specialists, as well as London-born Grace Wales Bonner. She began her career in 2014 with her CSM graduate collection titled Afrique. An intellectual approach to exploring Black identity in the context of contemporary menswear was quickly defined as her brand’s core and her immaculate execution made her an industry favourite. Since then, she has won just about every fashion prize out there, curated her own exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, and had Meghan Markle wear a custom Grace Wales Bonner design. PS. She’s 29.

Her fellow fashion award darling is Samuel Ross who has had quite an unorthodox experience of getting to the turnover of £12m his brand A-COLD-WALL* hit last year. Originally from Northamptonshire, he studied graphic design and illustration at De Montfort University in Leicester before being taken under Virgil Abloh’s wing, assisting him on Off-White as well as on Kanye West’s Yeezy line. In 2015, he finally launched a brand of his own. “Fortunately, my home fostered an incredibly creative environment, with memories such as building cameras with my father, discussing architecture, Apple products and visiting computer fairs,” Samuel shares.

His conceptual approach to garments as design objects was routinely labelled as ‘streetwear’ from the beginning. While this term first entered the mainstream fashion vernacular in the 90s, its overuse can almost exclusively be traced to Louis Vuitton’s AW17 menswear show which debuted Kim Jones’ infamous Supreme collaboration. In some ways, ‘streetwear’ has become fashion’s version of ‘urban’ — a catch-all term for all non-white style identities. “It’s a coded term, a lazy term. It’s quite tiresome, and illogical too. To be direct, it often reflects a lack of sensitivity and understanding displayed by the author,” Samuel says.

Another designer using their platform to spotlight other Black creatives is Nicholas Daley, who established the multi-sensory potential of garments at his CSM graduate show in 2013. Bringing together the influences his Jamaican father and Scottish mother instilled in him growing up, Nicholas asked legendary musician and artist Don Letts to walk in his graduate show. “He was really interesting, because of the way he blended punk-rock with reggae music,” he says. His shows blend together fashion with live music by performers from Nicholas’ own creative community. “I see fashion as a vehicle for saying so much more. It’s the three Cs — community, craftsmanship and culture — that are the backbone of what my brand is about.”

Proof of recent progress in terms of the representation of Black voices on the fashion week schedule comes in the new wave of emerging menswear designers exploring their multi-cultural backgrounds and complex definitions of British-ness. Priya Ahluwalia consistently merges her dual Indian and Nigerian heritage in both the techniques employed in the production of the garments and their presentation. With a sustainable outlook which includes reworking existing garments and textiles that would otherwise end up in landfill, Priya continues to build the puzzle of her past by creating the fashion of the future. Ahluwalia’s most recent project is a Jalebi, a photography book which captures Britain’s first Punjabi community in Southall through the lens of Laurence Ellis. “The best thing about London is the accessibility – there are so many talented people, as well as suppliers and manufacturers which helps with the process of collaboration,” says Priya.

Also based in South London, Bianca Saunders’ work focuses on introducing subtly feminine elements to templates of Black masculinity, a theme she originally found by looking at ‘yardie’ dancehall culture during her MA at RCA. “It was about the way some Jamaican men choose to groom – from shaping their eyebrows to the upkeep of hair,” she explains. “Appearance was key to presenting themselves.” For Black History Month in November 2019, Bianca curated a show in the stalls of Brixton Village, with some of the photographs by Ronan McKenzie starring her own family wearing Bianca Saunders SS20. Her latest presentation was one of the standout moments of London Fashion Week Men’s AW20, as she staged a presentation in which models danced in her fluid, modern tailoring at 9:30am.

The person behind the choreography was Saul Nash, a close friend of Bianca’s, who himself also creates garments that blend performance and fashion and focuses on the way clothes move. He recognises the big shift in the mentality of the designers which has helped create this network: “We’re now entering a generation where it’s not about elbowing each other to get to the top, but it’s about understanding that we’re all different and trying to understand how we can work together to get through it.”

According to a 2018 report by University of the Arts London, 47% of the students across their five universities (London College of Fashion, Central Saint Martins, Camberwell College of Arts, London College of Communications and Chelsea College of Arts) come from BAME backgrounds. Among them is Cameron Williams, a graduate of this year’s CSM MA class whose final collection stood out for its explicit yet subversive interpretation of his family’s West African heritage. He titled both the outing and his new-found brand Nuba, after “a somewhat derogatory name, given to generalise the Nilotic tribes of the Nuba Mountains of Sudan by Arab traders and settlers throughout history.”

For his graduate collection Cameron drew influence from his ancestry by combining the “indigenous influences of sculptural wrapping and frugal functionality, with the urban streetwear influences of my surroundings.” It’s what he defines as an “ideal of survival fashion.” His plans for the years to come? “Funding is also an important factor for me, which I see becoming more accessible as Black-owned businesses within art and fashion are providing financial grants to others, endorsing the progress of upcoming Black professionals. The aim for the near future is to develop into a cultural entity that promotes a world without tokenism, fetishism or colourism, and changes our approach to the understanding of indigenous cultures.”

Clearly, there are so many changes that still need to be made, but “the sole responsibility [shouldn’t] be on Black-owned brands to make these changes,” Charlie Casely-Hayford says. Instead, we need to “look at structures and how to create a culture of belonging, which means integrating a deeper understanding through the corporate structure — this includes looking at executive boards and people behind the scenes. The idea of just having a Black model just isn’t enough anymore as that won’t make a difference on a deeper level.”

“One thing I have realised recently is how closely my following watches me and absorbs everything I do and say,” Bianca adds. “As designers, we have this platform to reach a very engaged audience of young fans coming through, we have the power to influence for the better.” Hopefully, some of that power will in the future be amplified by those that are already on the top of the pyramid. What’s indisputable in our industry today is the imbalance between the contribution Black fashion designers have made to building contemporary fashion and the attention their work has been given. Instead of just sitting on advisory boards and offering their experiences as consultants, there need to be more Black voices guiding the industry from its highest seats. If it weren’t for those that came before, the fashion landscape we so deeply cherish would be a pale imitation of what it is today.

Credits

All imagery courtesy of the credited designers