This story originally appeared in United States of i-D, a series in celebration of diverse communities, scenes and subcultures across America.

Between Liberty City and Little Haiti, just before midnight, a cacophonous rave remix of Khia’s “My Neck, My Back” breaks the quiet lull of the Miami winter. Outside the Psycho Circus rave, a femme with a full beat and a rainbow afro holds court at the door. They sit on a red couch laughing next to a handsome masculine figure dolled-up in a clown nose, a Victorian collar and a leather harness over their muscular chest.

Inside the cramped rave space, angel wings, clown wigs, highlighter-colored platforms and broken fishnets abound. The air reeks of weed and tobacco, and everybody can take it in because there are no masks in sight save for the two on my face. The center of the packed dance floor has a makeshift rainbow tent framed by smoke and balloons that pop intermittently as the party rages. On the floor are half-empty cups, crushed joints, cigarette butts and discarded whip-it canisters the ravers are inhaling through balloons.

Afro-Puerto Rican DJ Marceline Steel, a core member of local trans, femme and queer-led rave collective Internet Friends, is on the decks — and their set doesn’t miss. Tonight, they’re serving distorted circus music, hard industrial beats and throwing in the occasional surprise. An interpolation of Paul Anka’s doo-wop classic “Put Your Head On My Shoulder”. An agitated, sped-up version of industrial producer Tzusing’s “4 Floors of Whores”. Chopped-up audio of a carnival announcer’s classic tagline, a haunting echo of a voice promising that “you won’t believe your eyes.”

In the midst of the ongoing pandemic, these words ring true. That said, the scene inside the warehouse comes as no surprise: the party never stopped in Miami. Over the summer, the city had so many Covid-19 cases that it held the unsavory honor of being the pandemic’s epicenter in the US, surpassing New York City and Los Angeles. When it came to staying in to stop the spread of the virus, a lot of young people didn’t quite get the message or care to hear it.

But the Psycho Circus scene in this little pocket of the 305, between two predominantly Black neighborhoods, is a far cry from the bottle service and lavish decadence of South Beach. For the Miami club kids that converge in these spaces, raving is worth risking Covid-19. The underground organizers running the show meet their chosen family and make their living at these parties, something that was seriously threatened by the pandemic. With mass events out of the question, organizers with less money than the big clubs — the queer exiles that built their own table after the establishment refused to give them a seat — had to keep the party going, just a little differently.

After a year of virtual raves members of Internet Friends, including Marceline, Summer aka Cowboy Killer, and co-founders Gami and Keanu Orange, were clamoring for their community. At the start of 2021, with vaccinations underway and “safer partying” becoming a possibility, Internet Friends quietly returned with unofficial raves held in small spaces. Albeit not official Internet Friends functions due to the very real public health risks the parties pose, they maintain the queer underground rave energy of past larger parties and add a layer of intrigue, with party locations and flyers passed out via DM and word-of-mouth. It’s a speakeasy for the coronavirus era: talk to the right people or message the right account, and the map to queer rave utopia is yours.

“Raving is a form of therapy, a necessity for some people,” Marceline tells me in the parking lot of Versailles, an iconic Cuban restaurant in Little Havana. “It’s an escape, it’s a fantasy world —”

“It’s a church,” adds Keanu. “We’ve had a lot of people coming to us recently talking about how their family was [now] vaccinated, which was their first concern [with] going out. That’s why they’re going out now.”

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that the pandemic created two cities within Miami. In one, the coronavirus left morgues so packed it takes months to return ashes to mourning loved ones. In the other, boats blaring Bad Bunny’s “Safaera” were still racing down Biscayne Bay even as a strict lockdown was imposed last March. Chalk it up to the work-remote outsiders and spring breakers who flocked to South Beach to flout Covid guidelines, or the blasé attitude toward the pandemic among Floridians even before Governor Ron DeSantis irresponsibly and preemptively lifted restrictions. As far as nightlife goes, this drew the “typical” Miami clubgoer back to South Beach: rich, largely-white, straight and more concerned with bottle service than dancing the night away.

For Internet Friends, curating diverse queer underground spaces takes on a very different meaning. Partying is an interruption of the mainstream, an assembling of a fringe community. The collective — originally founded by Gami, Keanu, Skyler Schubert and the late Nick Gogan — started up in 2016 and quickly graduated from house parties and smaller warehouse venues to residencies at bigger clubs and music festivals. Driven by a commitment to diversity and a ‘fuck you’ to the gate-keeping and toxic masculinity that rules Miami nightlife, Gami — a Colombian trans femme DJ and producer soon to launch a radio station with Club Space — took it upon herself to become the change she wanted to see in a party scene without any queer femmes at the forefront.

“The Miami nightlife scene is very… straight,” Gami says dryly. “‘Rave’ is becoming a mainstream word that’s being thrown around at EDM-type events. To me, rave means truly underground music that isn’t as popular. It’s more about small communities in different places of the world.”

Warehouse raves and South Beach clubs aside, Miami’s nightlife has always been a haven for reggaeton, dembow, bomba and the umbrella of Latinx music some critics are now calling El Movimiento. The 305 has been indelibly influenced by the Cuban and Haitian immigrants that have come to start new lives, as well as pockets of Venezuelans, Colombians, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and communities from across the South American and Caribbean diaspora. One of the few North American cities where one can live comfortably without speaking a word of English, it’s only natural that the familiar drone of tun tu-tun tu-tun is a part of Miami’s landscape. With the prevalence of perreo, however, comes the ever-present issue of machismo within Latinx culture across the board. In a male-dominated and sexist scene, where are the parties run by femmes and queer people that want to throw it back without fear of being harassed (or worse) for merely existing?

Enter Out of Service, a Latinx femme-run collective that ran El Perreo, an inclusive rager that only played old-school reggaeton, until the pandemic shut them down. Comprised of four self-described perras — Nathalie Perdomo (the Mindfulness and Inclusivity Perra), Sabrina Diaz (the Political Education Perra), NYC-based Jesica Gutierrez (the Community Empowerment Perra) and founder Daniela Molina (the Head Perra in Charge) — El Perreo, much like Internet Friends, was born out of need for a safe space.

The collective formed when Daniela and Nathalie were coming back from a lackluster party blasting reggaeton classics in the car. Realizing the vibe on the drive home was better than the actual event they were coming from, Daniela assembled her perras and started brainstorming what would become one of Miami’s few inclusive perreo parties. At El Perreo, women, femmes, queer people and even those sober can grind and sweat to Daddy Yankee, Plan B and Tego Calderón without having to worry about the sexist expectations associated with nightlife spaces in Miami. Growing up in this city, where perreo intenso and grinding trains in middle school are the standard, coming-of-age with hypersexual expectations goes hand-in-hand with the actual pleasure of dancing. Since reggaeton was really only played at expensive clubs on South Beach, Out of Service’s parties offered an alternative curated specifically for the kids who grew up on the genre, but existed outside of its mainstream audience for years.

“It’s something that didn’t exist at the time,” Daniela says over Zoom. “I realized that we’ve all had such a similar experience growing up in Miami. Our first parties were in middle school, listening to reggaeton, crybabying, grinding… it started out of pure joy. It wasn’t until [the party] was created and we experienced it for the first time that we realized what had happened. When you step into El Perreo, it feels so much safer than any other party in Miami. We felt liberated, and it feels like a responsibility to continue being mindful, inclusive and empowering.”

The El Perreo parties made it a point to address several toxic aspects of nightlife in Miami, from the expectation to drink to the expectation for women to look a certain way. Since going virtual in March 2020, Out of Service has grown outside Miami, becoming a digital haven for young Latinx immigrants across the diaspora who may not have a safe space within reach. Aside from online parties, the collective has also shifted their energies to hosting Zoom workshops on the Black history of reggaeton and perreo masterclasses. These classes double as mutual-aid efforts with Out of Service redistributing class dues to activist groups in South America and the Caribbean, such as Puerto Rico’s Colectivo Feminista.

“The way that reggaeton started [is rooted in] patriarchy,” Sabrina, who leads workshops deconstructing the white male domination of reggaeton, explains. “That continues to be where the machismo comes from, because reggaeton has been consistently from the lens of men, and now it’s [through] the lens of white men, which is one of the reasons I feel like currently [the genre] is finding wide acceptance.”

The reflections on anti-Blackness in the Latinx community and in reggaeton as a genre span further back than last summer’s uprising. Contemporary reggaeton megastars like Bad Bunny and J Balvin had to publicly own up to and address their privilege as white-passing Latinxs thriving in a genre popularized by Black artists. In Miami, where the added layer of US exceptionalism comes into play, the conversation about the way Black and Brown people have been marginalized cross-culturally can be seen in reggaeton’s popular artists of the moment. Latinx identity, especially in the US, is often shaped by whiteness. The racial diversity of people all over South America and the Caribbean is boiled down to the oversimplified definition of “Latinidad”, effectively erasing Afro-Latinx individuals. When it comes to reggaeton as a genre, this gives white or white-passing artists palatable to the mainstream industry the upper hand.

“We are white Latinxs in the US celebrating this genre of music that we did not create,” Daniela says. “We’re not Black, we’re not from Panama, we’re not from Puerto Rico. I felt like if we were going to benefit from this movement, we wanted to give back. Fans of reggaeton can be very toxic, and there’s a very thin line between these people and ‘classic Miami nightlife.’ It was back in May or June [during] the Black Lives Matter protests that a lot of clubs here in Miami were being held accountable for the toxicity and racism that exists. I hope that when we open back up, those things can start to change.”

These efforts to diversify the scene are among the many ripple effects of 2020’s reckoning with racial justice. Queer nightlife has always had radical under and overtones, but the personal and the political are entwined when it comes to Internet Friends. Before they were organizing parties, Marceline organized the biggest Black Lives Matter protest in Miami last June, one that saw the shutdown of the I-95 highway. They disseminated the flyer via Internet Friend’s socials and built a team via Twitter.

One also has to take into account that DIY nightlife and the subculture surrounding it, even in our current context, goes deeper than flouting public health concerns. In Miami, the underground raves and reggaeton parties worth their salt are run by communities opposed to the white cis-heterosexual powers-that-be. For Black, Brown, femme, trans, non-binary and queer party organizers, nightlife means creating a space that exists outside the bounds of a society built to actively work against them.

“My main issue is we really didn’t fuck with how all of these lineups had no Black people on them, no trans people on them, no femmes… there was no representation,” Marceline says. “Since we started our own safe space where we go out of our way to book Black people, there’s more Black people at the club and so many queer people I’ve never met before Covid. It feels safe.”

“After SOPHIE’S death and [Nick Gogan’s], it made me realize more and more that nightlife and raving is essential to many queer bodies,” Gami says in a follow-up interview, after a positive coronavirus test kept them off the dance floor for a bit (she has since fully recovered). “It’s so crucial to our sanity and mental health. We have all of our chosen family in these spaces.”

There will always be work to do to diversify nightlife, the music that drives people to the dance floor and the people running the parties. But the efforts of collectives like Internet Friends and Out of Service, the birthing and subsequent thriving of these spaces, speaks to a zeitgeist that yearns for a party where everyone can take part. As Western countries with resources emerge from a year-long public health disaster, while the rest of the world holds its breath, the hope of queer party organizers is that we return to nightlife spaces kinder and more open.

In Miami, where the toxic South Beach party scene will always dominate the collective imagination, it’s vital to nightlife’s survival that we listen to what the pioneers of the queer underground are bravely proposing. It goes further than the bottles popping and forgetting your worries on the dance floor. It’s about being brave enough to imagine and materialize a euphoric, more welcoming era of Miami nightlife.

“Every rave utopia is different; they’re little cities where people make their own laws and core ideals and fantasies,” Gami says. “It’s truly a utopian fantasy, once you’re really involved in it.”

Listen to a special mix that Marceline Steel of Internet Friends made for i-D here.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more culture. Tune into United States of i-D here.

Credits

Photography Fernando Manuel.

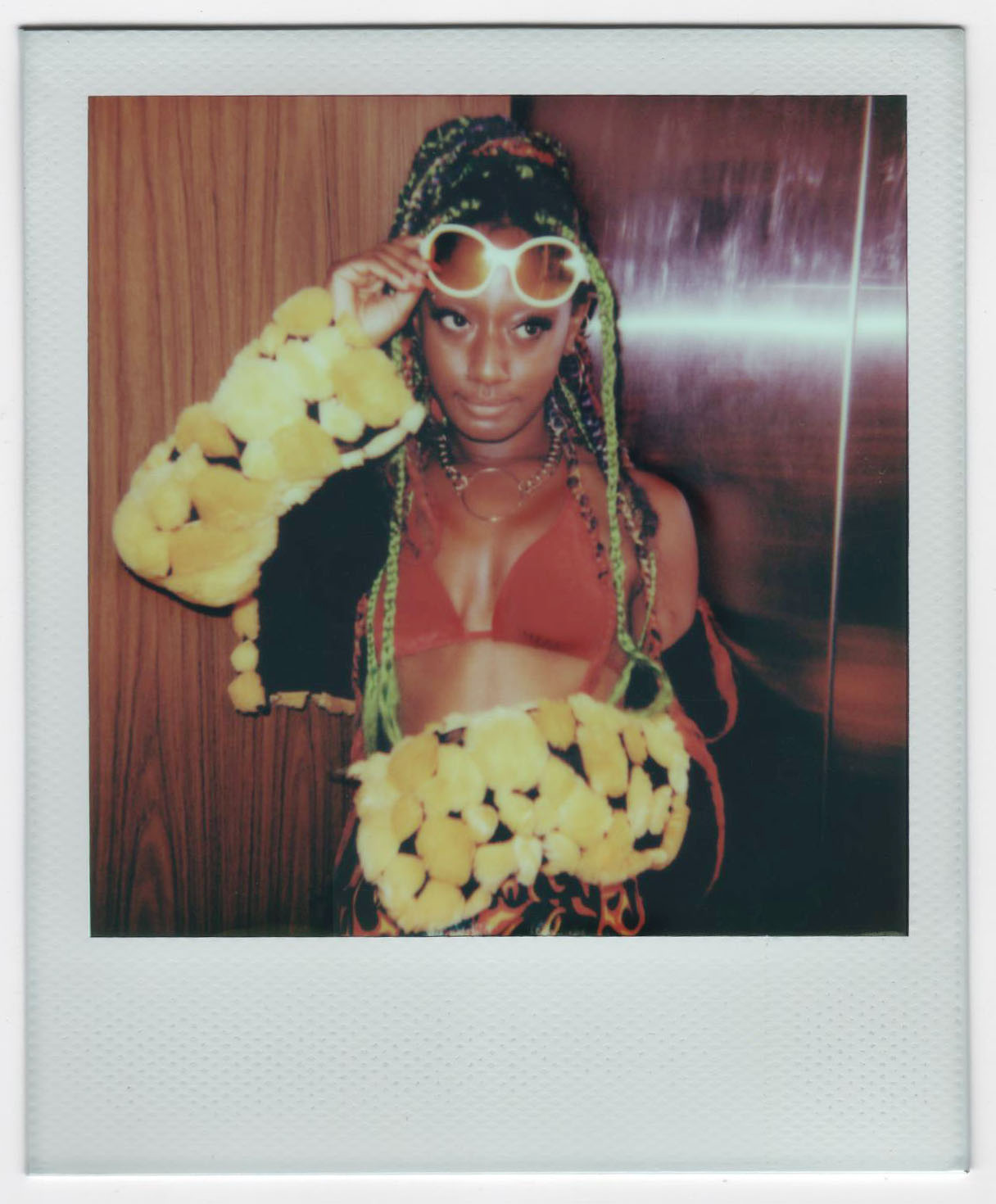

Polaroids by Atika Chadha

Photo and Lighting Assistant Isabella Osorio