Pakistani artist Misha Japanwala’s work reclaims an Urdu term that is loaded, pejorative, and capable of crushing a person’s spirit. Beghairati Ki Nishaani: Trace of Shamelessness (on view in New York City at Hannah Traore Gallery (through July 30th) counteracts the force of shame by celebrating diverse bodies in her hometown of Karachi.

Misha began creating sculptural garments and body casts in bronze, copper and gold metal coatings at Parsons School of Design, starting on her own body. As she began sharing her work online, some reacted with ire: “people think my work is so disgusting, and so offensive, and, by way of my work, me,” she reflects during a Zoom call. “Just seeing that [word beghairati] come up again and again and again really made me think about this word and what it means… As an artist, it’s like, Hey, look at look at my work and look at what I have to say, so you’re opening yourself up to that vulnerability.” But she willfully rejected the venom slung her way and its sexist, dismissive implications. “At my core, I know that what I have to say through my work is important. And the documentation of our bodies as they are is necessary. And if that makes me shameless, if that makes me a beghairati, then that is one of the most beautiful words in the Urdu vocabulary to me.”

The NYC gallery show encompasses three series, all underpinned by the same philosophy of inclusivity and boldness. “Shamelessness and the way the patriarchy uses it to wield its power doesn’t affect just women. It affects all kinds of marginalized communities. In Pakistan, this includes queer and trans Pakistanis… it would be nonsensical to create this body of work about beghairati and shamelessness and not have and not have them be part of it.” It’s all the more resonant given that in May, the Federal Shariat Court ruled that certain sections of Pakistan’s transgender law — notably the right to a self-perceived gender identity — do not comply with Islamic principles.

For her first series, Misha cast bodies of friends — mostly artists — whom she qualified as “warriors of shamelessness.” It’s an homage to her Karachi community, to those who deserve to be taking up physical space via a celebration of pendulous breasts and yawning bellybuttons. Her second series is called “Hands Of A Revolution,” an ongoing commemoration from the wrist down that honors the Karachi journalists, educators, photographers, and other intrepid figures bettering society at their own risk — including a controversial anonymous female comedian who satirizes Pakistani stereotypes.

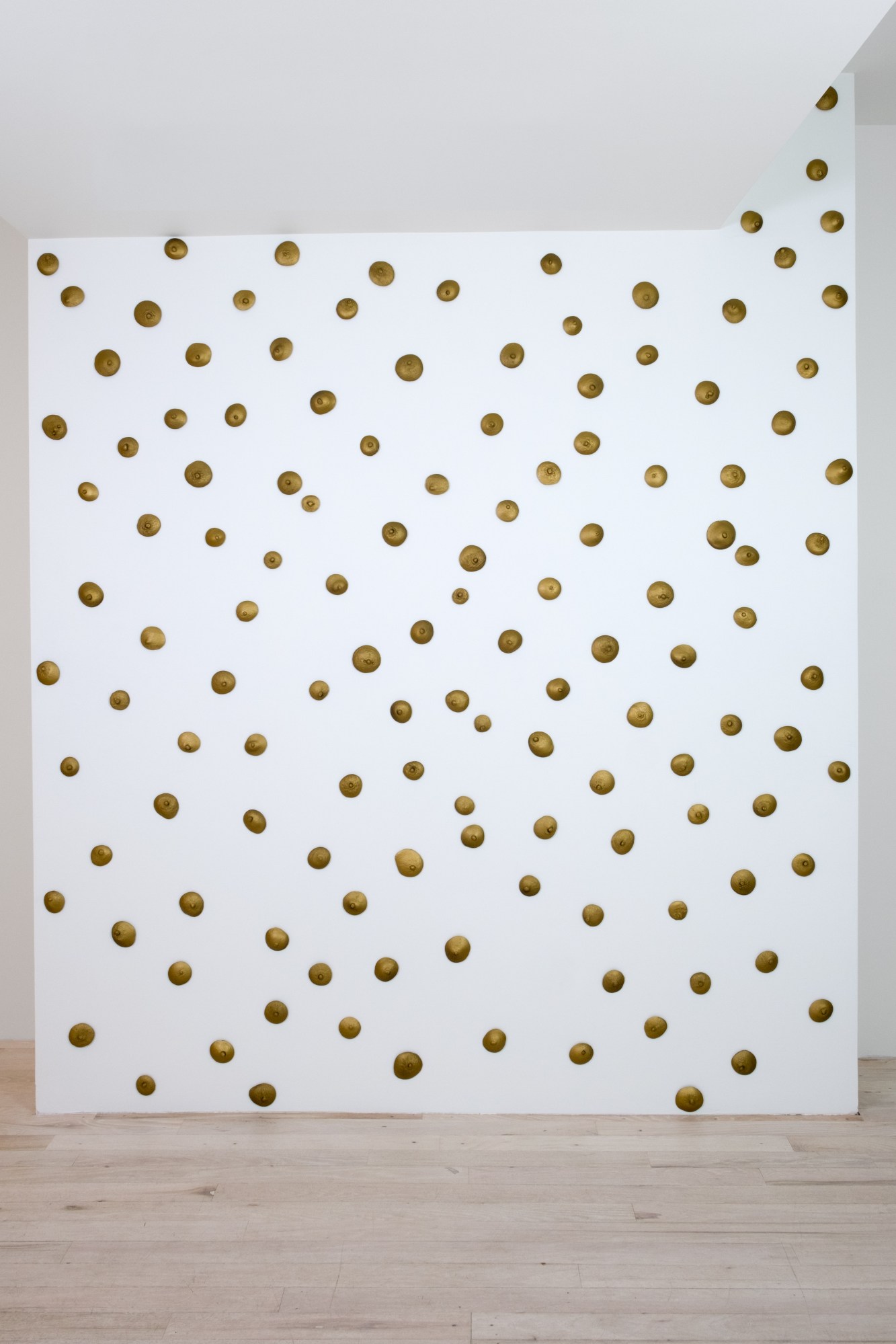

The final strand is as simple as it is powerful: nipples. “I was like, you know, I’m here with my materials, and it would be cool to get some nipples. So I posted an open call,” Misha notes. “I said, anyone over the age of 18, if you’re in Karachi, and you want to have your nipple molded, I will keep your identity anonymous so that you feel safe… you’ll be done in under 30 minutes, and I would love to have you.” She thought a few friends would humor her, but “I was just really overwhelmed by the response… I wasn’t even able to schedule everyone who said they wanted to be part of it. But it was very important for me to say yes to as many people as I could, because it takes a lot as a person in Pakistan to be like, Hey, I’m gonna show up to this stranger’s house, and take off my clothes and let them mold my nipple — who even knows what she’s going to do with it? That was really meaningful for me that people placed that kind of trust in me, and my work.”

In the end, she molded over 70 people’s nipples in back-to-back sessions. “And it’s just all ages, all kinds of nipples in terms of the shape and texture, which was so beautiful and wonderful to see.” It was all the more intimate via the meaningful conversations that sprang up during the process, with people disclosing their complex relationships to their bodies. “Some were like, if I told my parents I was coming here, I probably wouldn’t have even been allowed.” Misha calls this “quiet shamelessness.”

“They just did it so that they could have that experience and know that their nipple is existing in the gallery. I think it’s so beautiful, right? That it’s just for that person, and no one else.” She made connected collages of “nipple clusters” that, to her, evoke barnacles and fossils. She intends to continue the anonymous nipple series beyond Karachi: “just open up the studio and have open calls for nipples and have people come in and be part of this.”

Taken altogether, Misha’s work is rooted in body adornment. At the gallery, the series function as standalone artworks, but ultimately, Misha is shifting the parameters between art and fashion. The notion of wearability comes into play, as the armor-like casts are handmade in very thin layers. (Lupita Nyong’o made a statement on the Tony Awards red carpet in a custom breastplate piece by Misha.) “The fashion industry is very much rooted in what is trendy. Trends are not authentic. And my work comes from a very honest, and very vulnerable part of me,” Misha clarifies. She realized early on in her fashion school education that the industry wasn’t for her: “I’m not creating this work to be made every two-and-a-half months, pre-spring, pre-fall…” Moreover, the fashion narrative doesn’t align with her work. “I’ve been included in a couple articles in the past of, you know, trend roundup: breastplates are in fashion right now! It kind of makes me shudder when I read something like that. Because, for me, what my work is, it’s really a documentation — with this collection specifically — of marginalized people in Karachi, and in Pakistan, and not a trend.”

That said, she loves having the work photographed for editorials, because “having it be on the body and having real Pakistani bodies with their pores and their stretch marks and their texture, existing in high fashion spaces is really important for me. So much of the conversation in the past has been: how can we do everything possible to make sure that this is not present?” She adds: “I hope to continue doing this work for as long as I’m able to because of how important I think it is for our real bodies to exist as artwork and as historical records.”

Place is an important vector in thinking about her work. Misha was shaped by her upbringing in Pakistan, but studying in the US allowed her to take a step back and critically think about identity issues that transcend any one place. “I just want someone out there to look at [the work] and say, Yes, I understand it deeply. And it made me feel something. All kinds of people in Pakistan deeply appreciate my work, which I’m so grateful for, but to have people here [in the US] appreciate the work as well who aren’t Pakistani — that has been such a beautiful thing in and of itself, because the starting point of the work is very based in my identity as a Pakistani. But it’s something that I want to share with everyone, regardless of their heritage, or where they come from.”

Misha makes work in Pakistan, but exhibiting it there requires more circumspection. “I could put on a breastplate and go out onto the street and have someone take a photograph of me [in the US] and people would look at me like I was crazy, probably, but you know, I wouldn’t feel unsafe for doing that. But definitely, my work existing in public spaces in Pakistan — me or someone else wearing the work? I’d worry about the safety aspect.”

Because so many people react fiercely to her work, and to vivacious embodiment in general, she feels she has to justify herself to those who fume: How dare she be making the work she makes! “It would be wonderful to exist, and to just make the work because I fucking want to, and for no other reason, you know?” she says. “But we’re not there yet.”

Beghairati Ki Nishaani: Trace of Shamelessness is on view in New York City at Hannah Traore Gallery through July 30th.

Credits

Images courtesy of Hannnah Traore Gallery; Photography Aleena Naqvi