This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Out Of Body Issue, no. 367, Spring 2022. Order your copy here.

On an early August morning in Santo Domingo in 2005, I remember packing my bags to go home. I wanted to bring all the small things I had collected over the years: a plush toy, a collage book, some magazine clippings. I had a diary, some pictures and clothes I’d never worn before. That afternoon, my grandma drove me to the airport and checked me in as an unaccompanied minor. I was going home to somewhere I had never been before; I was thirteen years old and on a flight to New York City from the Dominican Republic.

Where are you from? Where are you really from? For the last seventeen years I’ve been faced with these questions. Being biracial, and having spent most of my life abroad (and abroad, like home, is relative), answering this question has always been difficult. Like many of us, the pandemic gave me time to take stock of my identity and how I relate to the Dominican Republic: What if I’d never left? Would I still be an artist today?

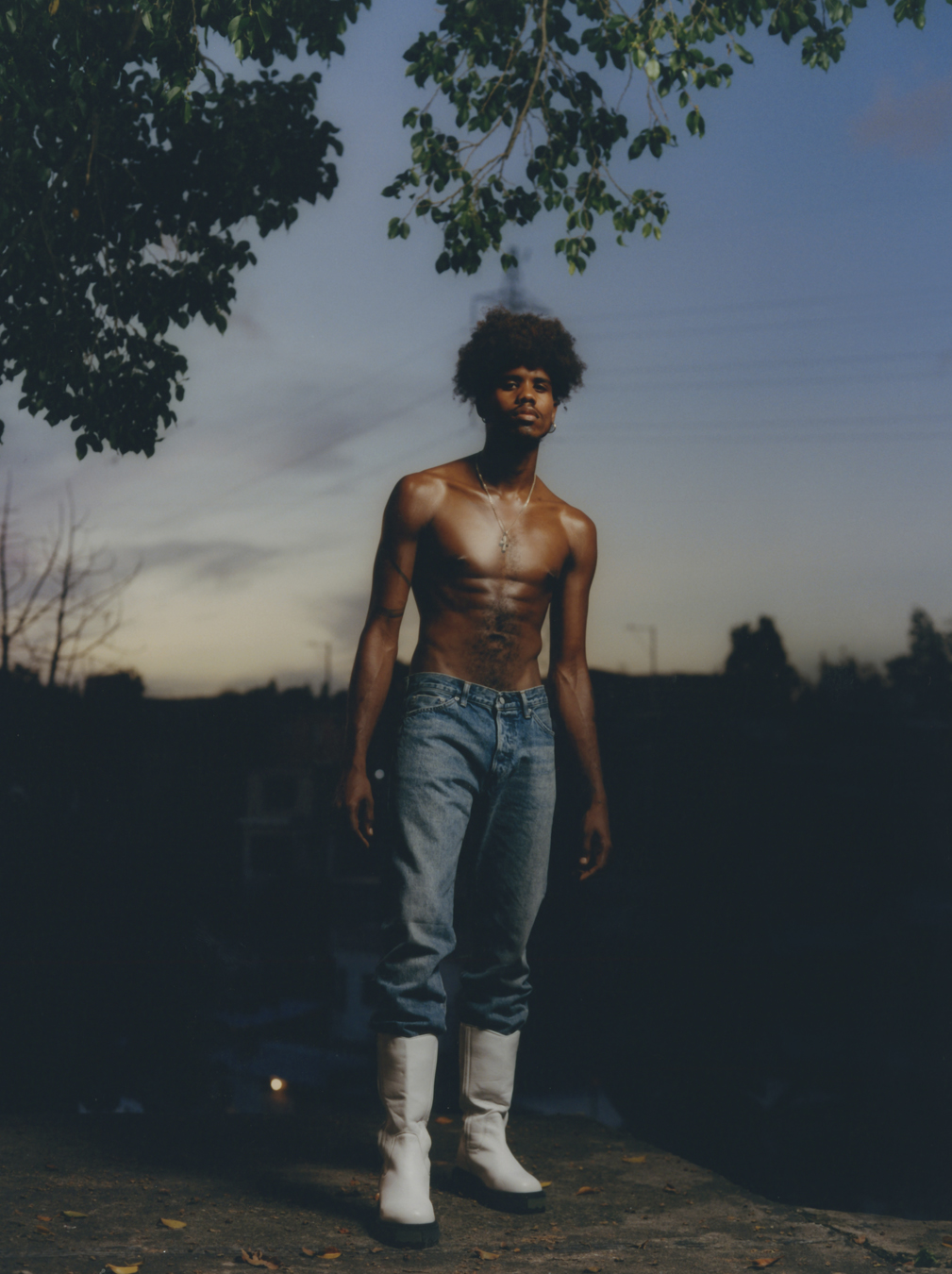

I’ve travelled to the Dominican Republic many times as a grandson, nephew, and cousin, but I’d never returned as a photographer. From the outside, it’s easy to romanticise moving to another country, but the truth is the immigrant experience is complicated and the expectation is to assimilate. To let go of the past and become the new; to learn a new language and a new culture; find new ways to celebrate and create new traditions. Sometimes all we have left are emotional heirlooms.

Since leaving I’ve always had a feeling of missing out and losing touch: of not being Dominican enough. Or Latino enough. Or Black enough. And while it’s painful to constantly shapeshift, a beautiful and often overlooked aspect of migration is the ability to constantly reinvent yourself – to challenge your ideas of identity and the things that represent you to the outside world.

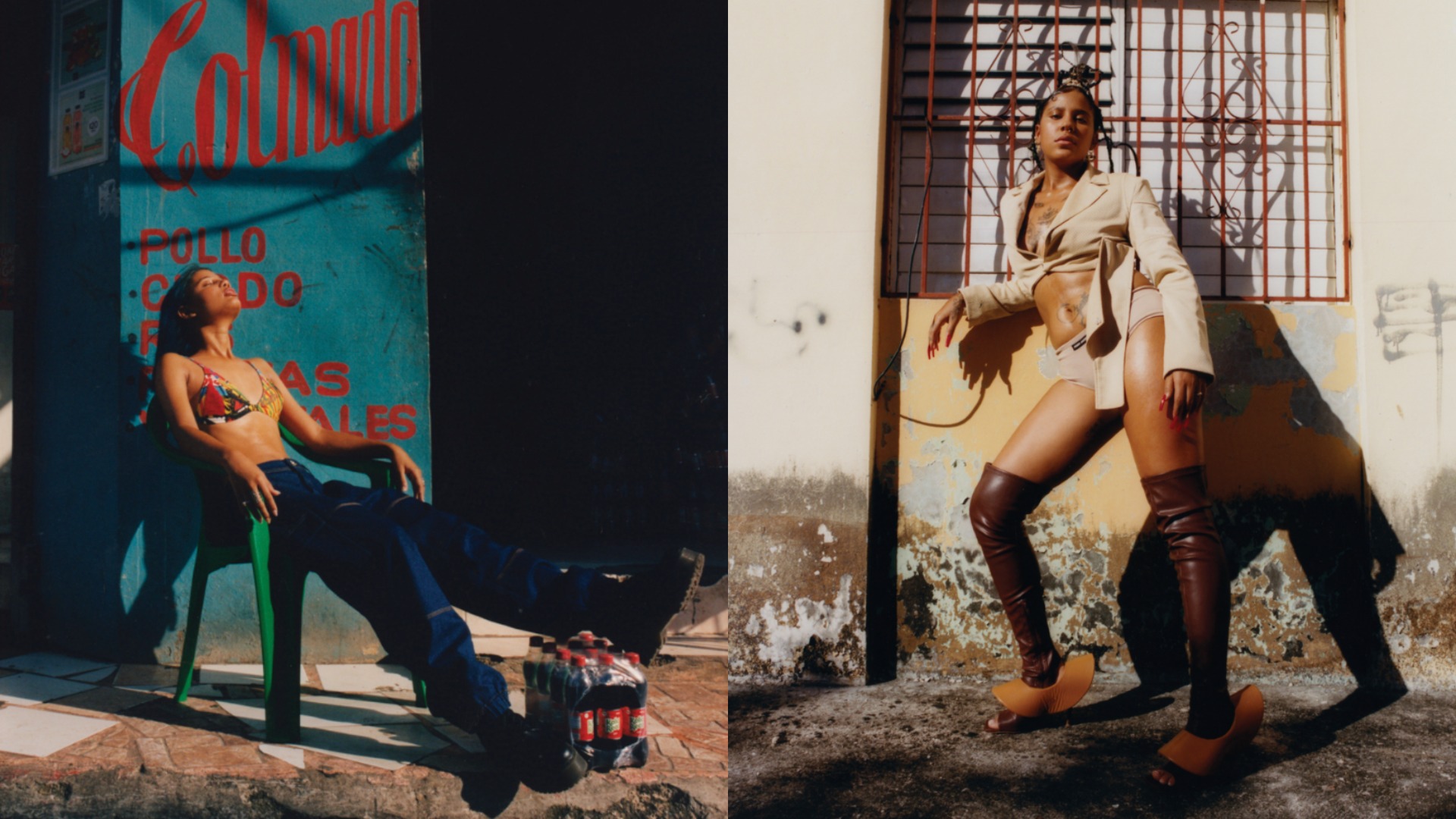

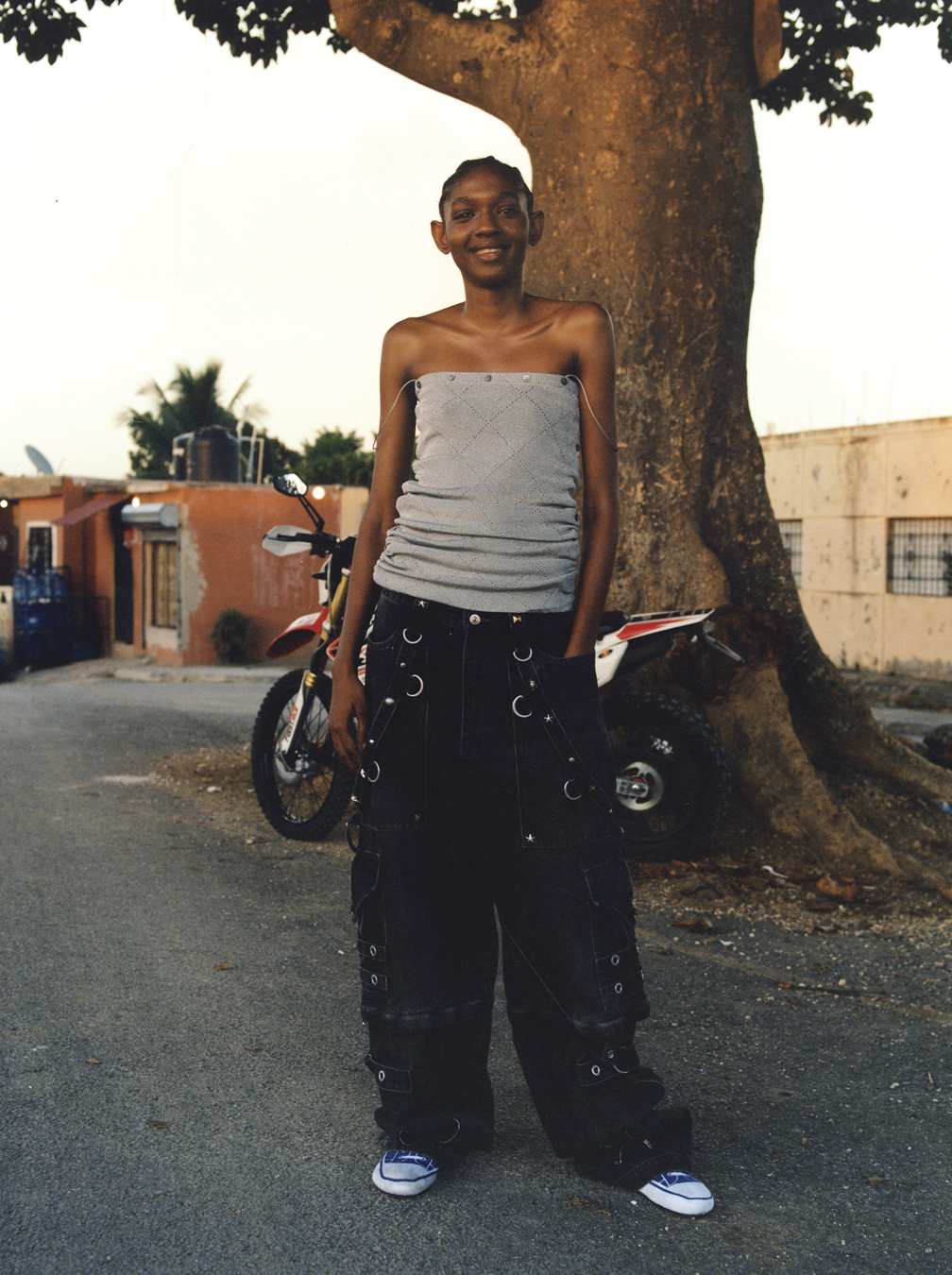

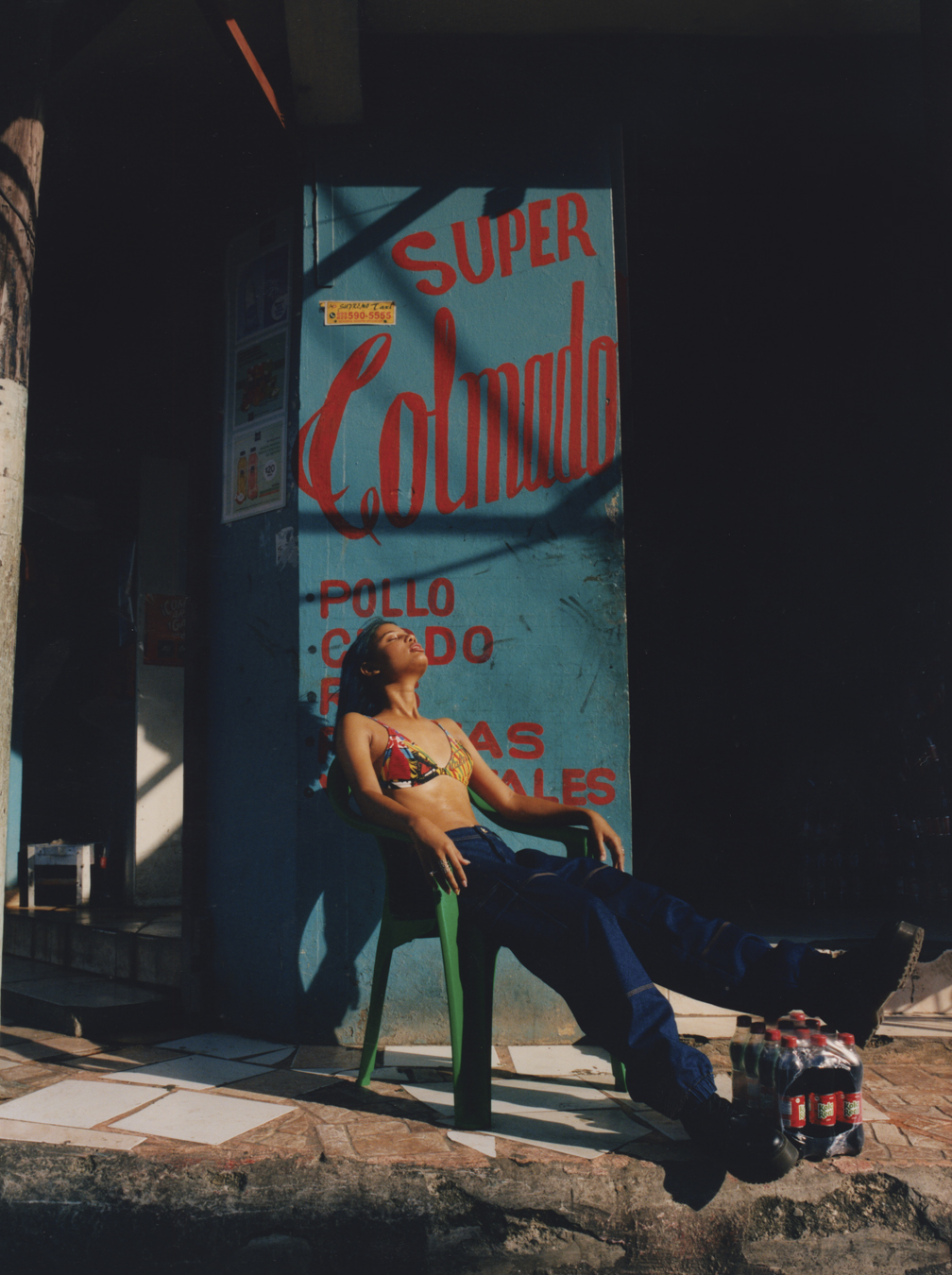

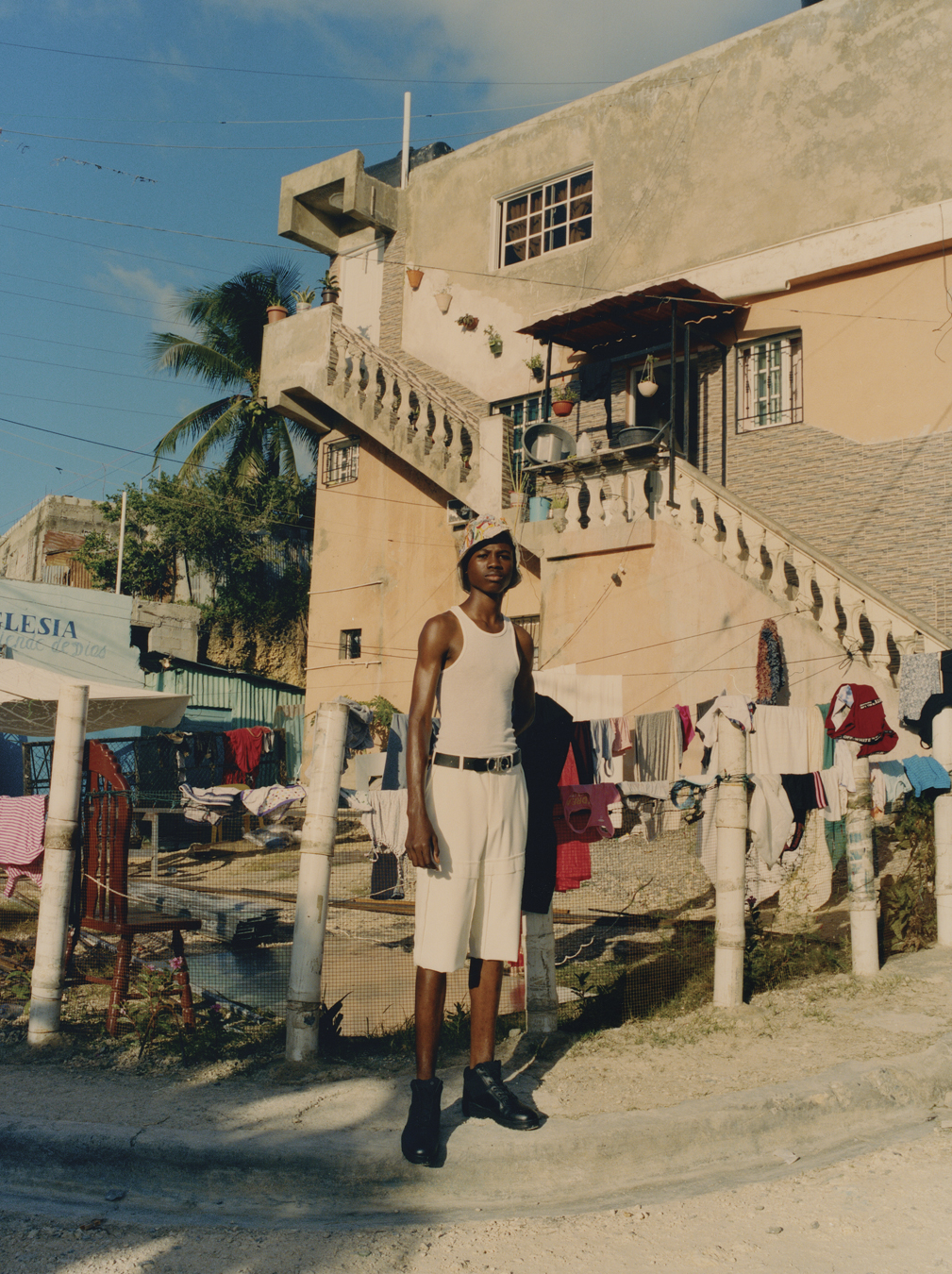

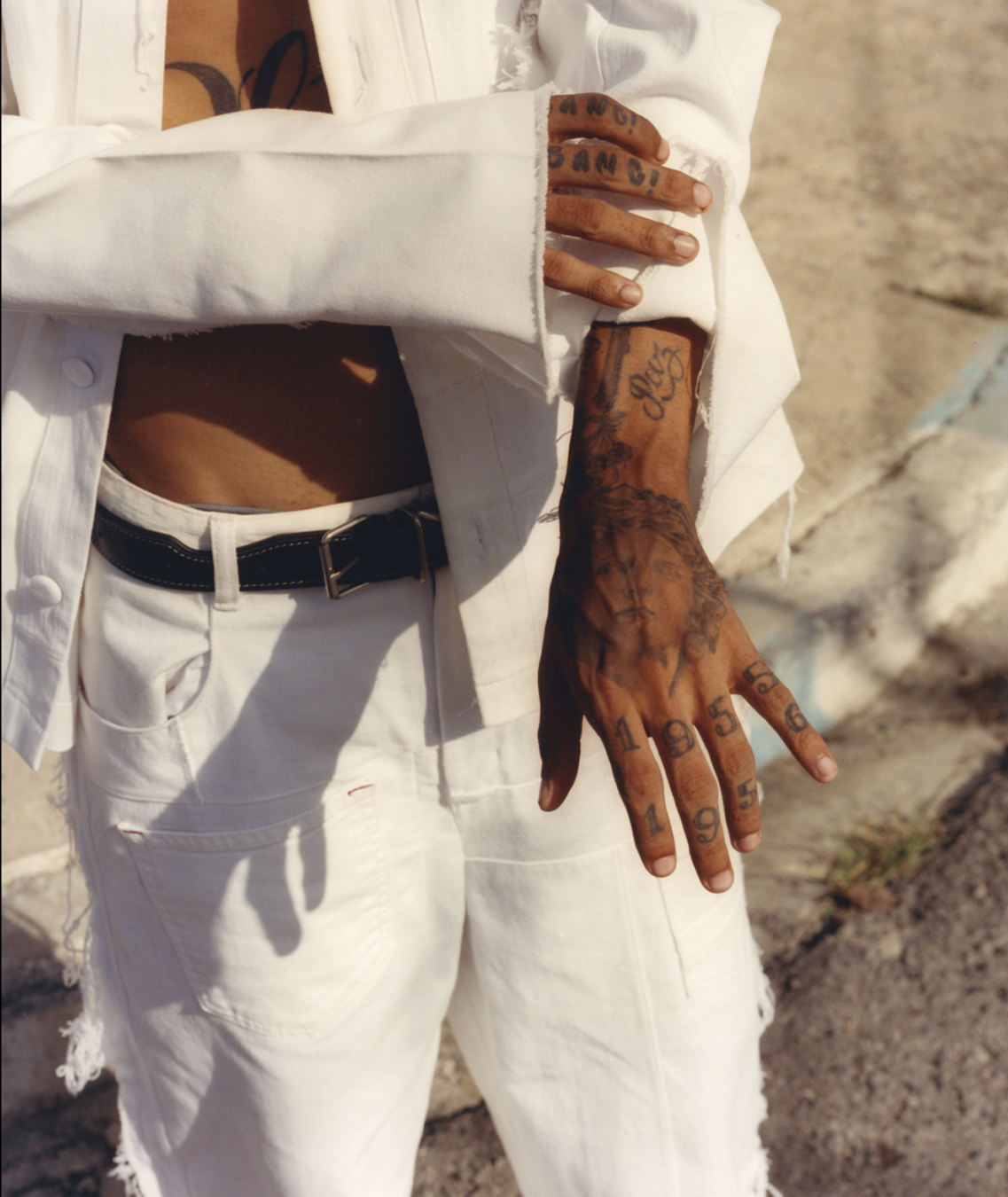

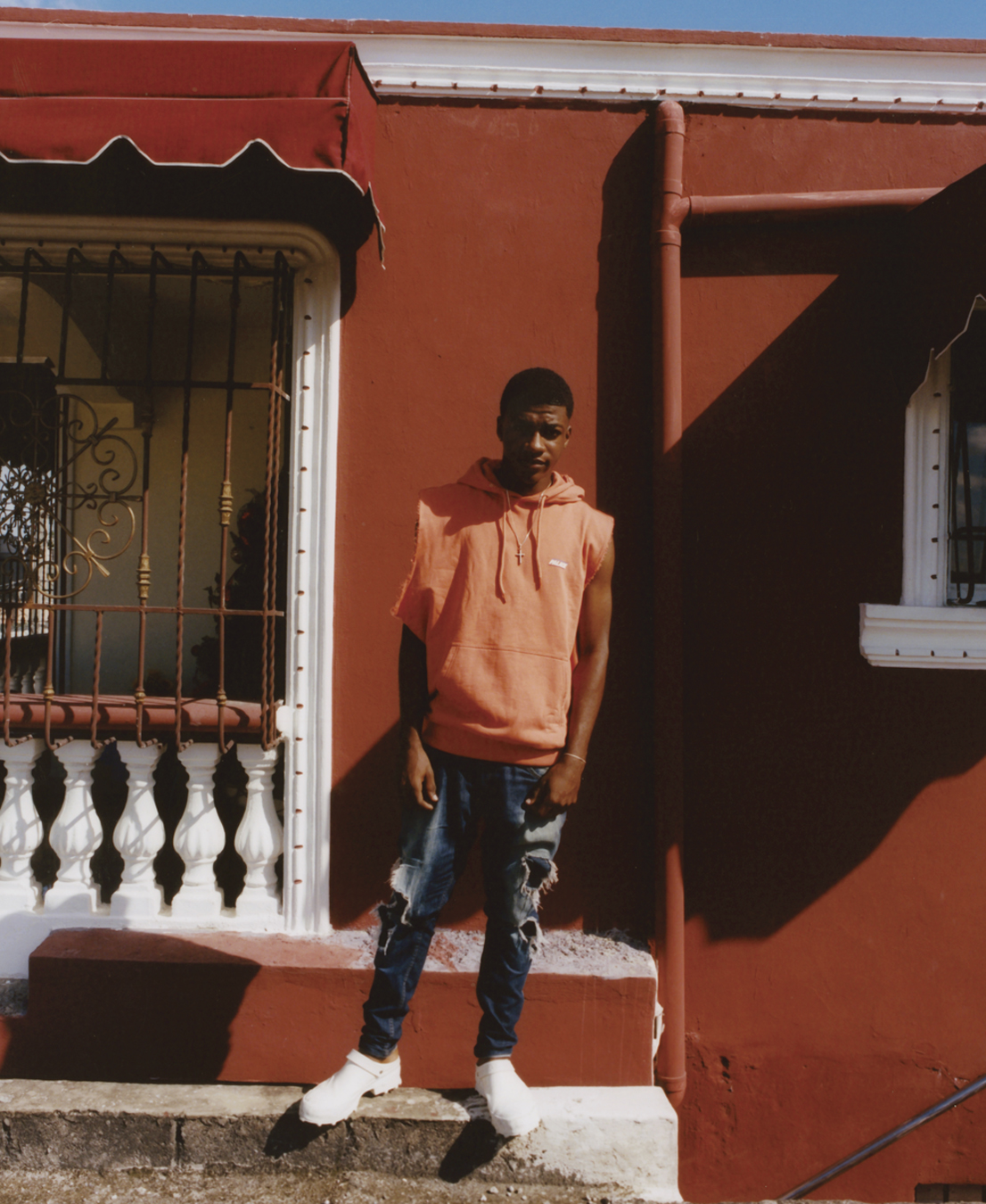

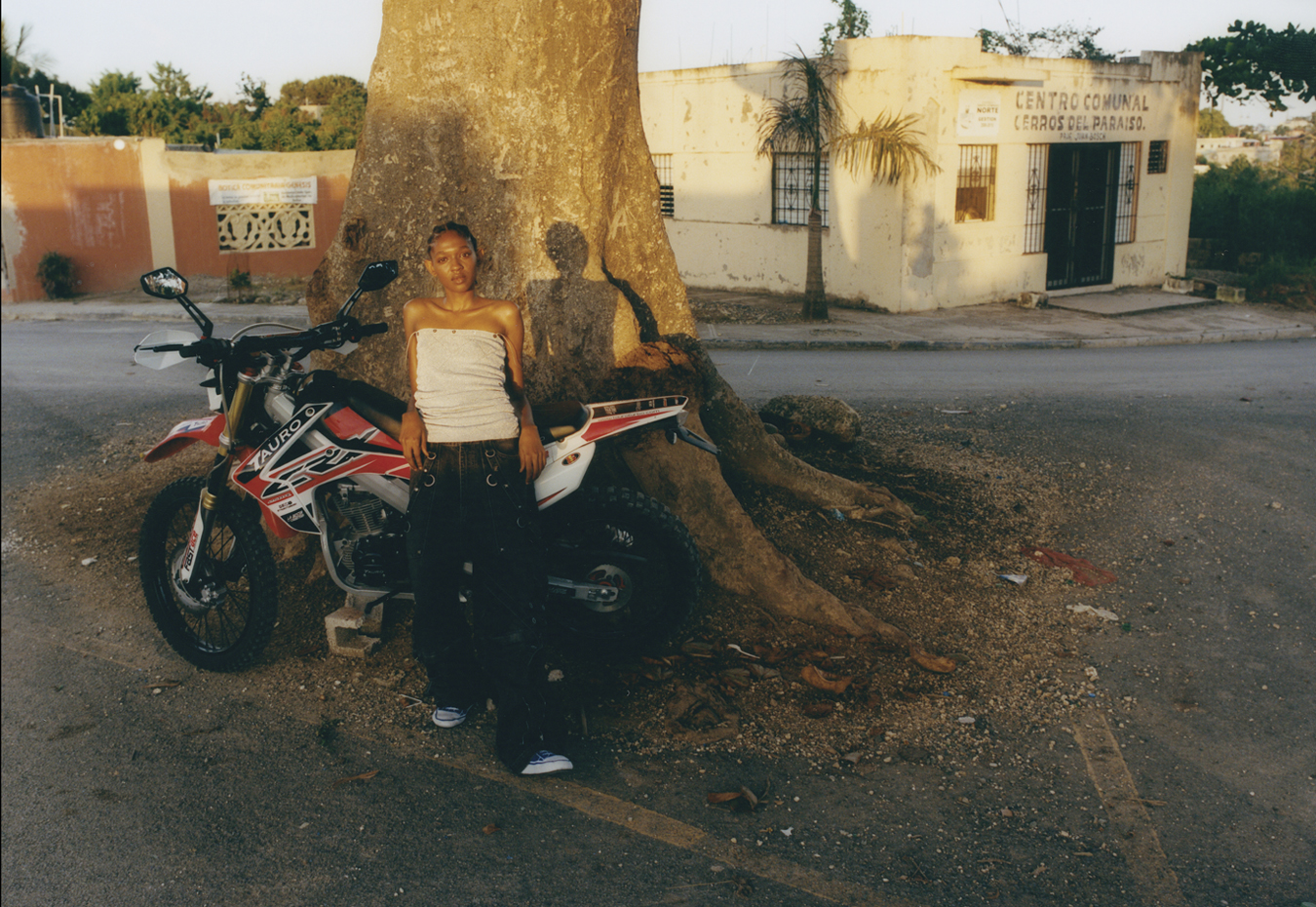

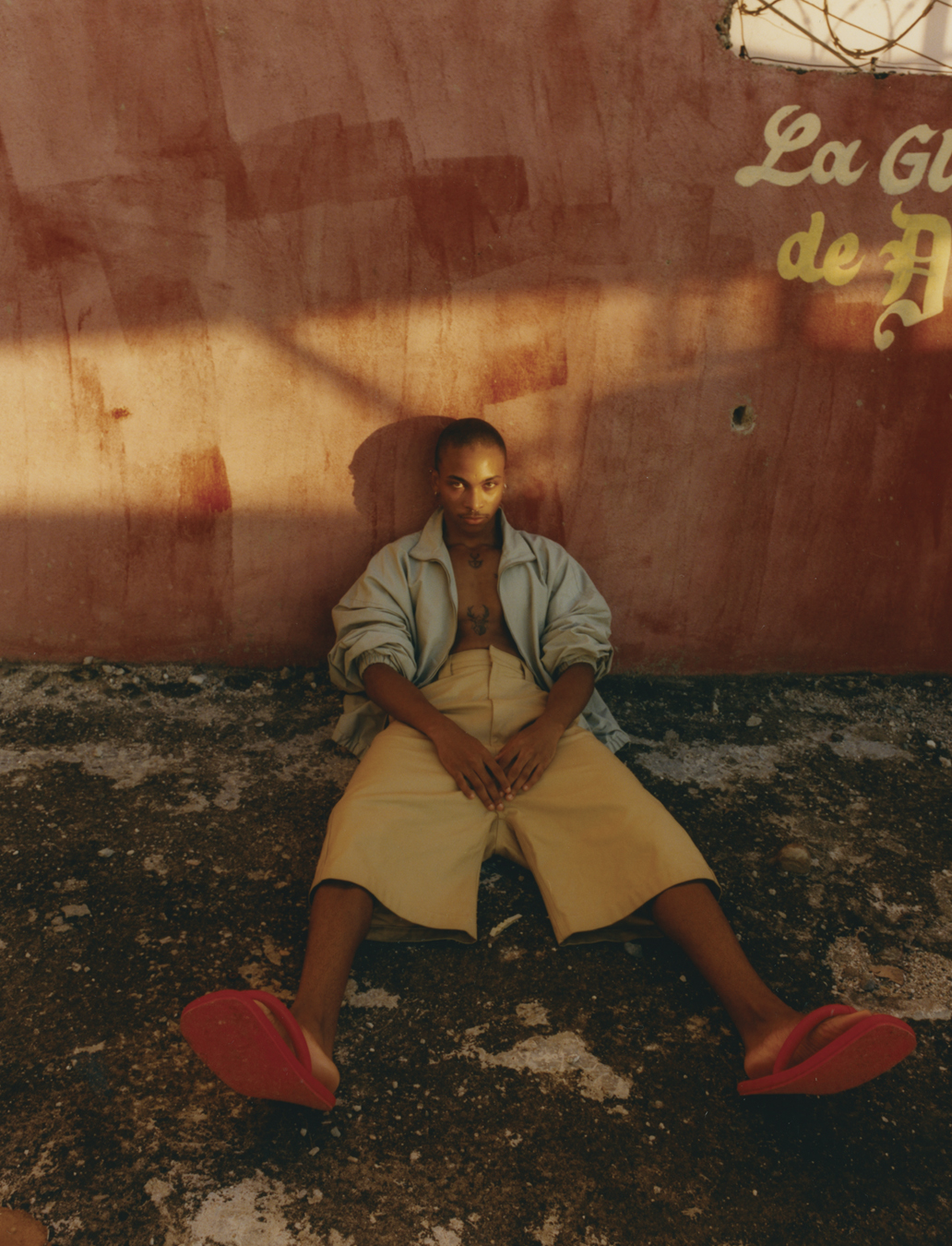

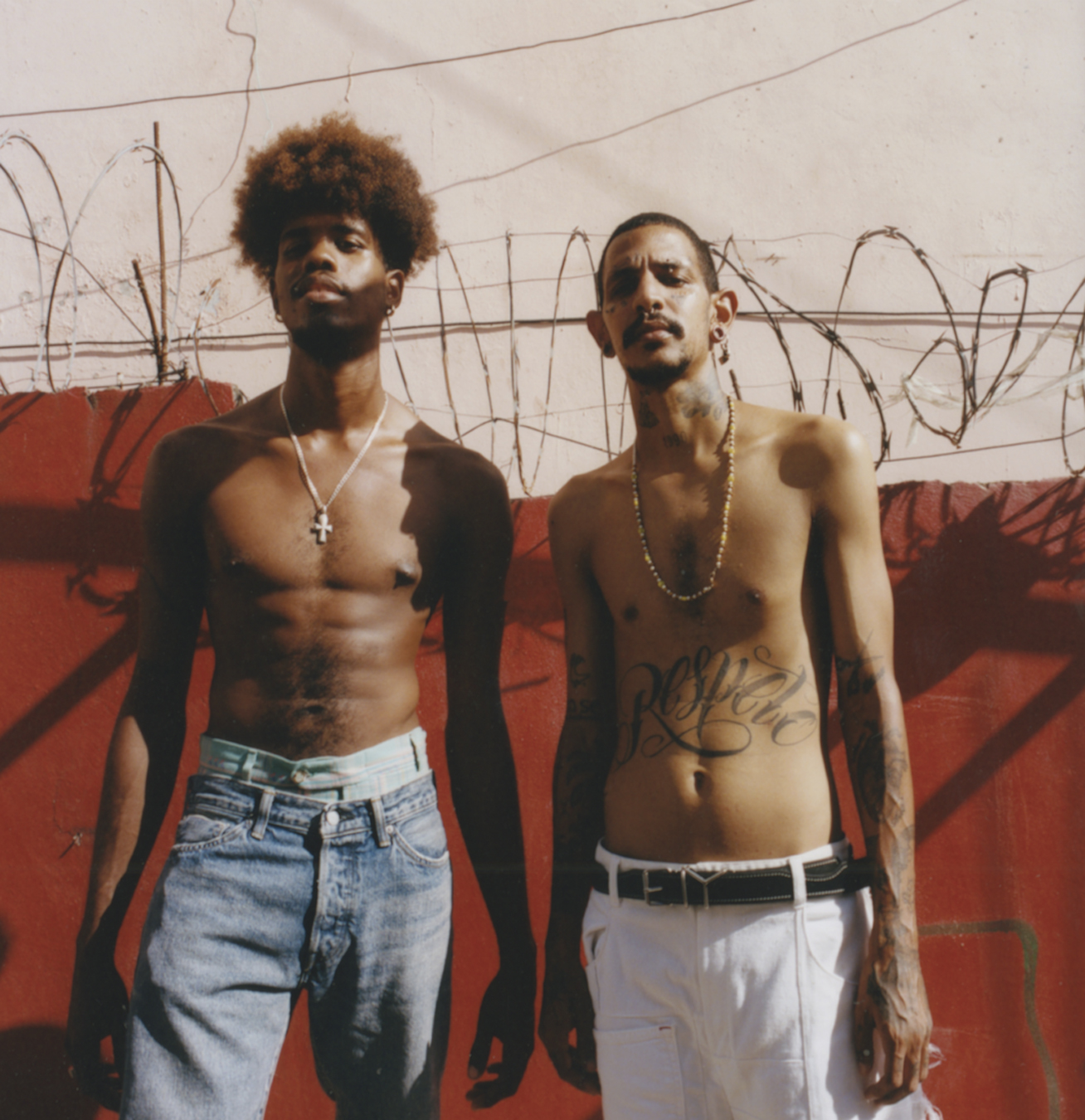

When Milton and I began working on this project we wanted to jettison all the tired cliches of the Caribbean and look at how things have evolved there since I’d been gone, to show the streets as they are: honest, bright and colourful. We wanted to find people like us, a community beyond family.

I started researching the barrios I used to visit as a kid and learned about teteos – clandestine street parties that began after the pandemic. We discovered Tokischa and her music, and I was instantly drawn to her. In many ways we share the same scars, and it’s healing for me to see her shine despite her lived experiences. I feel pride when I see her challenging everything that is expected from a Dominican woman. Tokischa introduced us to a design collective named Tiempo de Zafra, founded by a couple who returned to the Dominican Republic after growing up in the US. Their studio was teeming with artisans of all trades making one-of-a-kind sustainable garments by upcycling second-hand pieces. Several pieces we shot were made by them, and it was there we also met Railin, who ended up doing everyone’s hair for the shoot.

My family was there every step of the way, too. I enlisted my cousin Yanely to produce and help with casting. My cousin Gabriel helped Milton style, my aunts Milagros and Josefina opened their doors so we could have a basecamp, and my uncle Leo drove us around. The day we arrived in the Dominican Republic we took off on motorcycles, to find spots in the neighbourhood where we could shoot and get to know the kids we were photographing, and while riding around it started to pour with rain. In a big city, surrounded by concrete and stone, it’s easy to see the rain as a nuisance, but here it is also re-energising; life falling from the sky.

As a kid I remember spending afternoons during the rainy season waiting for the downpour to come so we could run outside and play in the rain. It felt very healing to be home, to be stuck in the rain again. The following days were arduous and hot because all of our locations were far from the ocean. Yet on the very last day, in true Dominican fashion, we drove to the beach on Sunday and ate delicious fish and swam all afternoon. That evening on the way to the airport, I thought of how rain welcomed us in and the ocean was sending us out, two baptisms of sorts.

Recently on a commercial shoot in California, someone in the team happened to be Dominican and said he’d never seen someone like him be the artist on a shoot. I hope that this moment continues to happen: that more migrant kids have access to the arts. To dream of things less linear, not limited by how they look or where they’re from. I think of my niece who has Chinese, British, and American ancestry, and I see a generation of kids whose “homes” are everywhere. Not limited to where they or their parents were born, but instead defined by communities they build.

Being part of a community goes beyond geography: belonging is a choice. It is about sharing values and being accountable to each other. It’s being open to other people who can make any place feel like home. After seventeen years of travelling back to the Dominican Republic, it wasn’t until I got to make art with my family and friends there that I finally felt like I came home. My sense of belonging was incomplete without the feeling, without the genuine conviction, that they also belong to me.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more.

Credits

Photography Mitch Zachary.

Fashion Milton Dixon III.

Hair Railin Pichardo.

Make-up Marco Castro using Marco Castro.

Photography assistance Alec Vierra.

Production Billy Kiessling.

Production assistance Gabriel Montero Sánchez.

Special thanks to Andrew Gethins, Adam Belhen, Milagros de Oleo, Josefina de Oleo, Leonel Sánchez, Stephanie Rodrigues, Edgar Garrido, Jankovic Feliz and Hostal Riazor.

Casting Yanely Sánchez.

Models Camilla, Frank, Danuska, Christian, Ariel, Leudy, Jabba, Sonnis, Yonathan, Elisabeth, Liliana, Gabriel, Tokischa and Yanely.