“Maybe if I was high, I’d have a little more wisdom!” Armistead Maupin laughs, as he slouches into a hotel lounge sofa. I’m here to ask the iconic gay author what the future of queer America under Trump’s rule might look like, but he doesn’t seem to think much of his opinion. “I’m not good at spouting that kind of knowledge,” he admits. “You’re doing what Christopher Isherwood would do years ago when I interviewed him: trying to make me sound like old Mr Queer!’”

Armistead Maupin turned 73 this year, but his mellow and wry sense of humour, something that’s imbued his work, shows little sign of fading. He seems to cherish that title he once bestowed upon Isherwood some years ago. After all, thanks to a career spanning three decades that made him a legend of LGBT literature, he’s definitely earned it.

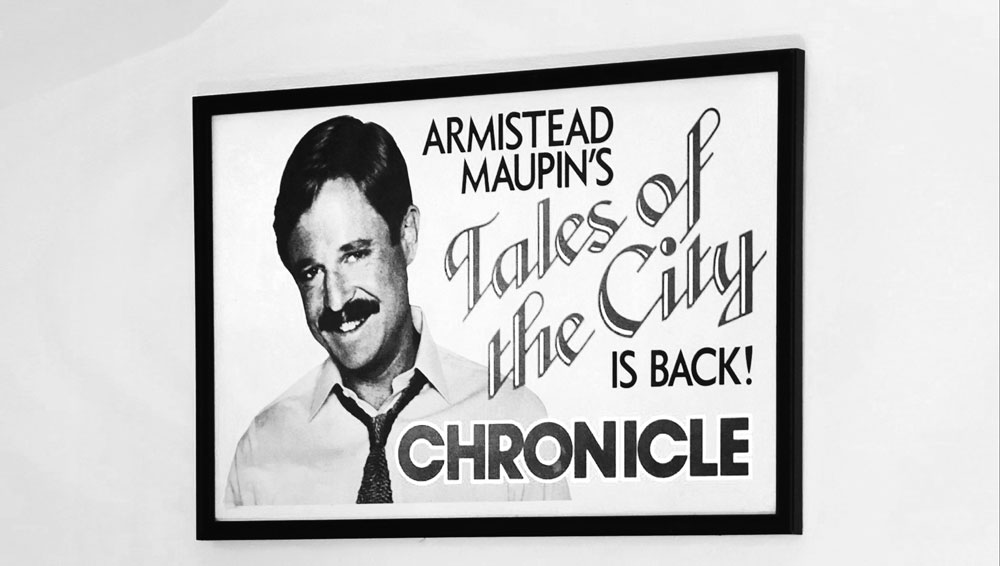

Back in the hot hysteria of 70s California, Armistead started writing Tales of the City: a long-running serial about the soapy, underground activities of the people spending their lives at the fictitious 28 Barbary Lane, San Francisco. Its characters — funny, fresh, and full of various and voracious sexual desires — were reflective of Armistead’s progressive new hometown. Featuring furtive encounters in gay bathhouses and pot-smoking landladies, he managed to hook a whole generation with his stories, unleashing them five days a week on to the readers of the San Francisco Chronicle. Later, they were turned into a series of internationally bestselling books, and fame followed.

“Maybe if I was high, I’d have a little more wisdom!”

Much to his excitement, a new audiences will be meeting the folks at 28 Barbary Lane in 2018, as Tales of the City gets the Netflix treatment, starring a good friend of his, actress Laura Linney. The miniseries will take place in Trump’s America, with a more diverse cast. “But the spirit of the thing is going to be the same,” he reveals. “[That] we’re all in this together, and we all make ourselves faintly ridiculous over love.”

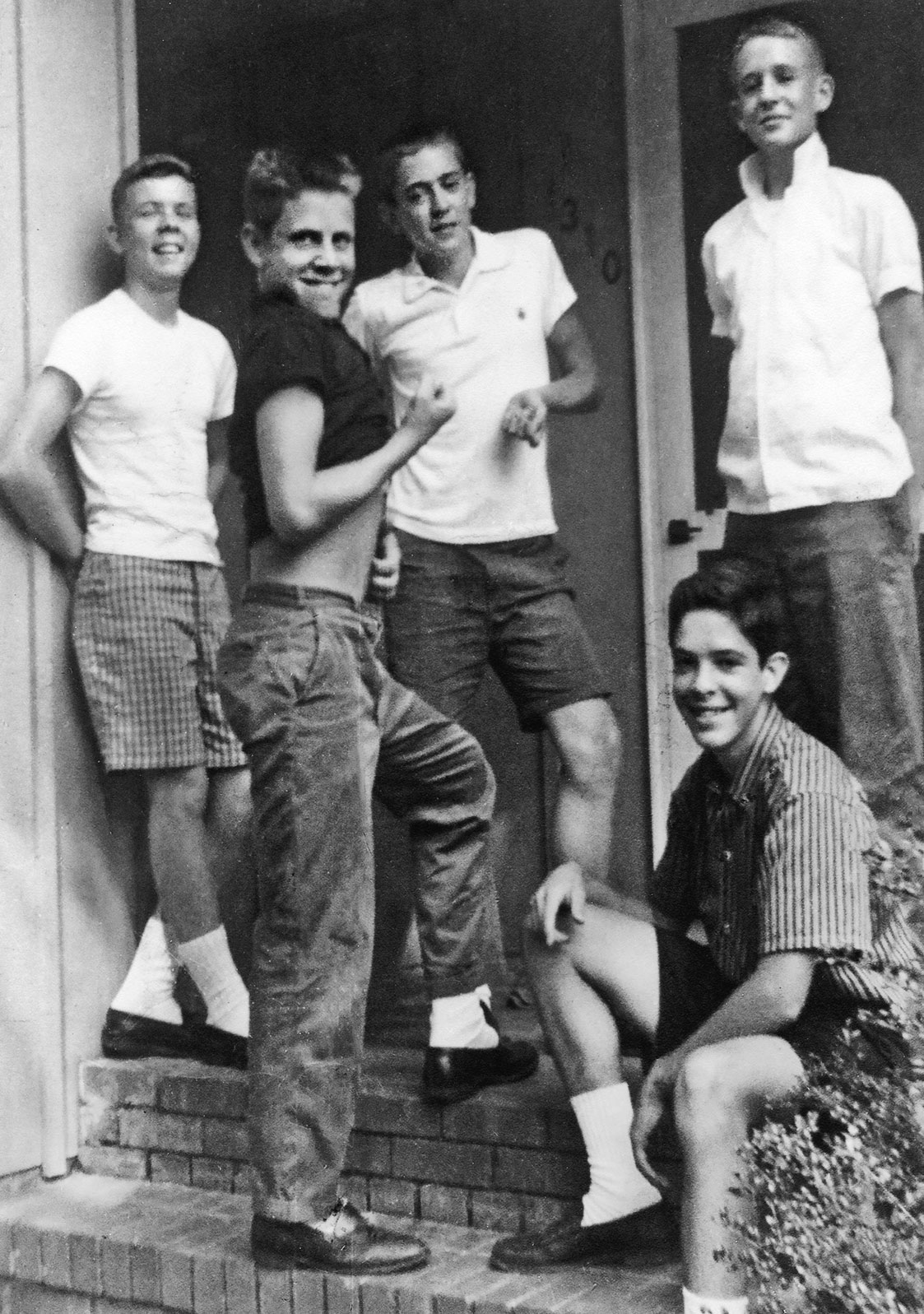

But Armistead’s life hadn’t always been so frothy, fun and fuelled by melodrama. His own struggles as a young gay man, growing up in a stiff and traditional North Carolina town before heading off to fight in the Vietnam War, are chronicled in his long-awaited memoirs Logical Family. Poignant and achingly funny, it captures the eventful life of an author whose pioneering work captured modern sexuality.

Coming out, for Armistead, was something that took time. Fearing his parents’ reaction and having grown up in a such a proudly Conservative American state, he avoided the topic for much of his youth. He finally came out to them in a touching letter wrote from the perspective of Matthew, his Tales of the City protagonist, at the age of 33, having found his safe spot in San Fran. “I’ve always felt that queer happiness begins and ends with coming out,” Armistead begins, on the pressures associated with unveiling your sexuality. “Most of us have to come out all day long, because there’s always someone out there assuming that we’re straight.” So is it easier now for young people to be open about it? “There’s no question,” he believes, “but that doesn’t mean there aren’t still difficulties, [or] bigots you’ll run up against at any given moment. The trick is not to waiver in the face of it.”

Bigots are still one of queer America’s biggest problems. By allowing them to step forward and have their voices heard more freely, Donald Trump has made it problematic to be proud of your heritage. Now, Armistead says, America’s heritage is seen “in a very narrow way” by most of the country. “[They] think of it as saluting the flag, refusing to kneel at a football game or going off to a mindless war. I don’t think it’s anything to aspire to.” But that doesn’t mean the term is lost forever in a cesspit of American history — Armistead gives it more uplifting definition. “What I love about my country is [our] provision of freedom, and the civil rights we’ve fought for over the years,” he says. “To keep fighting for those rights is to be patriotic.”

The battle is ongoing, but there’s still an undeniable sense that things are getting easier for the queer youth as time progresses. We have Armistead and many of his friends — like the late politician Harvey Milk — to thank for that, who campaigned for equality in a time where being gay was still a sociopolitical burden to carry. “I don’t demand appreciation. I know what we did, and I’m confident in that, but I can understand that people who weren’t there [might not] understand what the struggle was,” Armistead says. He, like many others, lived through the Aids crisis of the late 20th century, an event he calls “the worst kind of holocaust” that claimed the lives of some of his closest friends.

“We’re inventive people, and most of us who have finally come to taste complete freedom aren’t going to give that up easily!”

As gay men were being demonised, the community grew closer, banding together to fight back. “There was no greater proof that decent human beings were at the centre of our community,” he says reflectively. “In the same way women rally today, gay men bore up under the worst [circumstances].”

For many, Armistead included, creative outlets act as an escape of sorts, a skill we can owe to our often ostracised and confusing childhoods. “As I say in the book, ‘We’re lone gazelles in the buffalo herd of our closest kin.’ You develop a private, interior life — and that makes artists,” he believes. “We have great power in that we can change the culture, because we can start telling our own stories.”

Creative queer allies with a platform barely existed back then; Armistead was part of a very small pack. The group was so small, in fact, that he would regularly be booked as the headline entertainment on the world’s biggest gay cruise. ‘Who would those guests be today?’ I ask. “The latest winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race,” he responds, “and lots of divas!”

Initially unsure of the drag scene, put off by the awkward incarnations he remembered from his youth, Armistead has changed his mind lately. He’s been meaning to get into Drag Race, since he’s “talked to too many people who find it enormously uplifting and fun” — it also helps that the latest winner Sasha Velour called Tales “the queerest book around.”

Armistead Maupin has seen the LGBT world for what it is, but he’s still enraptured by the fantasy, enchantment, and potential of it too. Despite it all, he remains hopeful for its future. “We’re inventive people, and most of us who have finally come to taste complete freedom aren’t going to give that up easily!” he says. Does he have any advice for the younger generation of queer men and women? “Keep making a noise, [and] keep fighting,” he says. You should trust his judgement. “It’s tiresome,” he admits. “I’ve been doing it for forty years!”

Armistead Maupin’s Logical Family is out now.