Mustafa was 12-years-old when, as a young poet, he first made the news in his home city of Toronto for a poem he wrote, A Single Rose, addressing inequality. His teenage years were vastly different from those of his peers: at 15, Mustafa wrote and performed a song with Nelly Furtado on Walk the Walk; at 17, he performed at the 2015 Pan Am Games as the official poet laureate of the event, and at 19, he had been co-signed by Drake. By his 20th birthday, he was collaborating with The Weeknd, was appointed to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Youth Advisory Council, and unbeknownst to him, had a Grammy nomination on the horizon. But as Mustafa’s career was blossoming from locally adored poet to a national cultural figure, his city was changing, too – only for the worse.

To understand Mustafa, we must understand the social and political conditions that he’s responding to in his music. For many years, Toronto was an underdog, itching for the access and recognition of its American neighbours. But by the 2010s, artists like Drake and The Weeknd had thrust the city into the global limelight, the city becoming synonymous with the sounds emerging from the underground. At the same time, the city had expanded to become the fourth largest metropolis in North America, but this came with consequences. Gentrification increased, the city’s affordability plummeted, poor neighbourhoods became sought after by developers, and inner-city violence rose exponentially.

The changes in Toronto have been personal for Mustafa. He saw his home neighborhood of Regent Park, Canada’s largest housing project, slowly deteriorate as urban planners and condo developers altered its essence, pushing out the working class and making space for middle-class, predominantly white, professionals. By the summer of 2018, things took another turn for the worse. Toronto saw its highest homicide rates in 27 years as gun violence plagued the city. In June of that year, Mustafa’s childhood friend, rapper Jahvante Sheldon Smart, known by his stage name Smoke Dawg, was killed during a daytime party in downtown Toronto.

“Smokey had a charm that was unmatched; he had this brilliant ability to make you feel loved. In Smokey’s presence, I always felt capable and that I belonged,” says the 24-year-old, sitting on a friend’s backyard porch during a recent late-spring evening in Toronto. Smoke, one of the city’s most revered emerging rappers at the time of his passing, had all eyes and ears on him and his creative collective, Halal Gang, of which Mustafa is now a member. “I remember when I was in Paris with Smokey in 2017 [for Drake’s Boy Meets World tour], and I thought, ‘That’s it! We survived it!’ I thought his death was impossible. It felt impossible. We went on tour, we went to Los Angeles. It felt like he had transcended the struggles back home.”

A few months after Smoke’s passing, while working on the album that would become When Smoke Rises, Mustafa released his first short film, Remember Me, Toronto. The documentary addressed gun violence in Toronto, bringing together artists and figures from rival communities across the city, including Drake, to share how they would want to be remembered. “When I look back to it and listen to the way those people are speaking, it actually eases some of my rage. After looking around, I realised there is no other proof of what we’re struggling with like this film anywhere else. I can’t find that emotion or level of fragility.”

As Mustafa crafted the songs that would result in his debut album When Smoke Rises, he thought of those same artists and communities who appeared in the film, including some he currently has tensions with. The thread running from Remember Me, Toronto to When Smoke Rises is Mustafa’s realisation that grief is a common experience for so many in Toronto and that his work is as much for their hoods as it is for his own. “The government systems dictate how some people are gonna live and some are gonna die,” Mustafa says, making reference to Achille Mbembe’s theory of necropolitics. “It’s so difficult to come to grips with. All the deaths that are happening… there is a greater system at play that leads us to the decisions that we’re making.”

When Smoke Rises is a 24-minute folk album of eight songs, thematically and sonically exploring the five stages of grief. While Mustafa’s music has always been rooted in storytelling, it was artists like Richie Havens, Joni Mitchell, Bill Withers and Neil Young that enabled him to see folk as the preferred medium for his expression. “I always kind of delegated folk music to white communities. Oh, like that’s what they do. But I appreciate it so much. And I knew that it had something in it that I thought was so rich and so powerful: the narrative ability, the songwriting, the poetry of it, you know what I mean?”

The ordering of songs on the album reveals the chaotic order in which we arrive at, and sit with, grief. Anyone who has lost a loved one to murder, a death so sudden, knows that each day invites a different experience of mourning. The first two songs on the album – Mustafa’s first two hits, “Stay Alive” and “Air Forces” – put forward the record’s central theme: the hope and yearning for someone to stay alive, and the paranoia, restlessness, and exhaustion that comes with maintaining that feeling. Separate explores the shock of loss in the beginning; of moving mechanically without being present. (“It feels like [being] underwater,” Mustafa tells me.) The track centers those most pained by premature grief – mothers, and features vocals by Mustafa’s mother. “The mother is the voice that you know and you recall and you remember when somebody dies,” Mustafa says.

After the numbness, comes the rage, one of the most vital and overwhelming components of coming to terms with a sudden loss. On the calm but chilly track, “The Hearse”, Mustafa chose to sample Sudanese songs of burial and war. “Without this song it would not be an honest account of grief,” Mustafa says. “Capo”, is an ode to friends grappling with the undertold act of grieving while incarcerated, and Mustafa wrote a verse specifically for English singer-songwriter Sampha who joins him on the track. In “Ali”, he sings about the loss of his 18-year-old friend in 2017, struck by a bullet on the front steps of his Regent Park home. The song ends with Ali’s voice from a local interview he did at the age of 10. What About Heaven explores the spiritual conflicts of questioning where someone is going in the afterlife, and whether they will be forgiven. “Islam is the way I understand loss,” Mustafa says. “It’s the way I understand where my friends went. It’s the pathway and rulings as to how I can help them, now that they’re gone.” When Smoke Rises concludes with “Come Back”, a plea for a return, or one last chance to see his loved ones who have transitioned. It’s the final stage of grief and often a sentiment that many find hard to let go of. “I wanted to explore my grieving process, my mourning process. How did it feel from beginning to end? That’s why it was structured the way that it is,” Mustafa says.

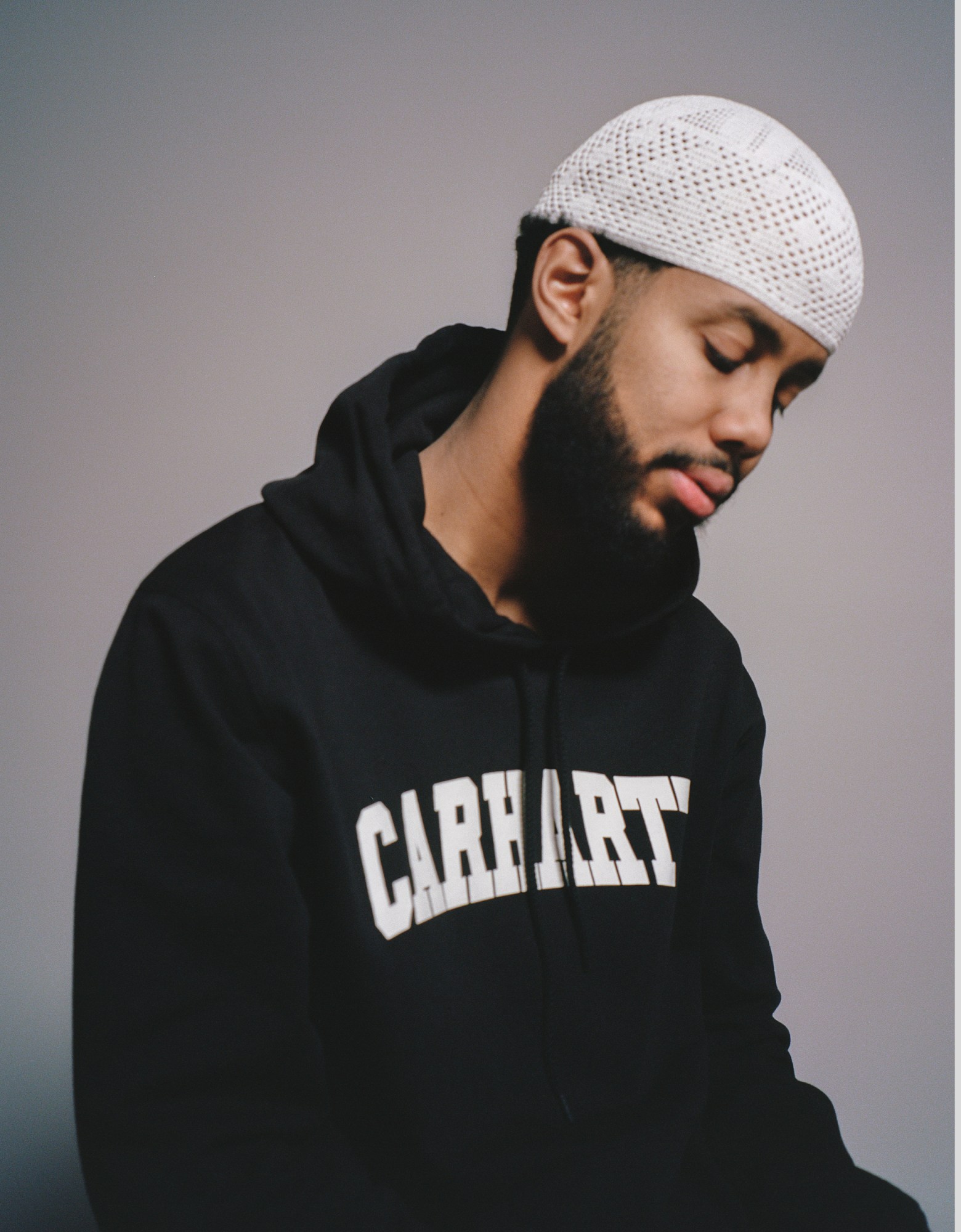

Though creating When Smoke Rises was a way for Mustafa to make sense of his encounters with loss, the decision to make music has always been a spiritual negotiation. For many years, Mustafa grappled with whether making music was the right path for him as a devout Muslim. When he and I first met in 2013, he was a teenage poet transitioning into making music, who always did his best to make time for prayer while we worked. It was obvious what was most important to him: his poetry, his community, and his faith. Mustafa’s devotion to Islam made him vacillate about whether or not music was the right path for him – some see music production as impermissible in Islam. “I don’t want to be the reason that people think that making music is halal and permissible. I don’t want to be implicated under judgment. That’s the truth,” Mustafa tells me. It was his goal to help people, and he considered becoming a doctor to do so. It took him a long time to arrive at a place where he could view music as a similar type of offering, and address whether it compromised his faith as a Muslim. “I would write songs and then I would stop completely. I would attempt to write poetry over instrumental chords, and I would stop that completely. That was my struggle. I couldn’t fully commit.” Mustafa took space from making music to confront these tensions and reached out to leaders in the Muslim community to explore what different Islamic schools of thought had to say about the permissibility of making music.

Smokey encouraged Mustafa to continue making music when he was alive, and the album is a memorial to the singer’s late friend. When asked how he wants Smoke to be remembered, he pauses before looking down, holding back but, eventually, releasing tears. He admits to me that it’s the first time that he’s cried about the heartbreak of losing his childhood friend in almost a year and a half – around the time when the album was in production. “He was a gentle person, and incredibly forgiving. He was an incredible person, outside of my love for him: so considerate, so empathetic,” says Mustafa. But he admits that it wasn’t until Smokey’s passing that he realised how big a heart he had. Smokey was taking care of so many people in Regent, particularly incarcerated folks, and Mustafa was overwhelmed with carrying on that work after he passed. “The difficulty of taking on those tasks by myself, it’s hard.”

When Mustafa completed When Smoke Rises, he had a physical reaction after playing it from beginning to end. “I was throwing up the day I completed the record. I realised [that with] so many of these feelings, I didn’t know I was feeling them at all. I was on autopilot.” Mustafa still struggles with his grief and admits that it’s difficult to listen to the album. He’s unsure of how certain tracks may trigger a feeling he hasn’t come to grips with yet and can count on his one hand how many times he’s revisited certain songs, such as Ali. Yet, while When Smoke Rises offers us the intricacies and cyclical effects mourning has on the individual, Mustafa’s debut album also offers something similar to how he describes Smoke’s character: something gentle, forgiving, and with the brilliant ability to make you feel loved.