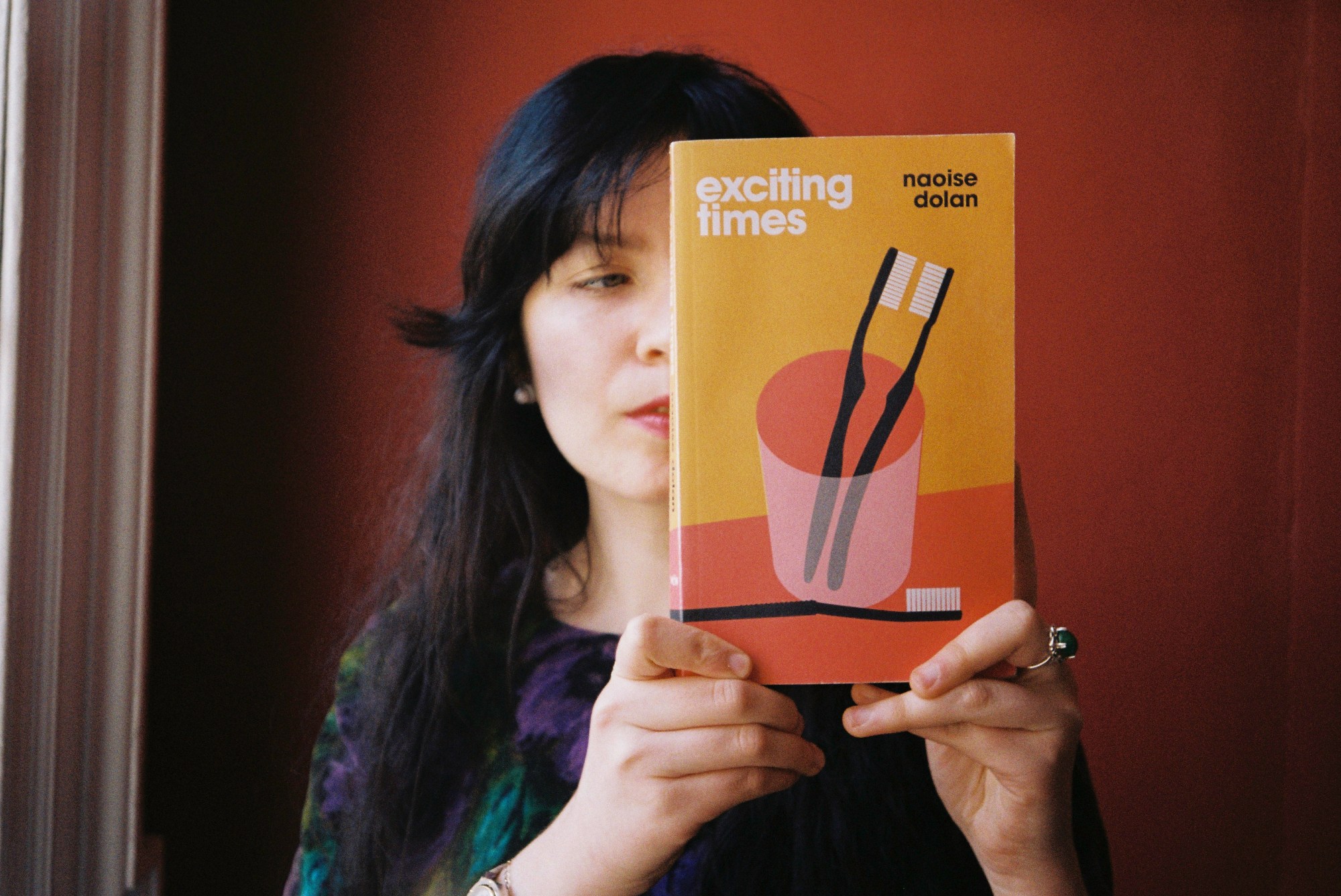

Naoise Dolan is fast becoming a big deal. Conveniently, she already dresses the part. Before our meeting in Outhouse queer library in her hometown of Dublin, Naoise warns she will be “serving a look”. She manifests in copper green and royal purple velvet, delivering on the promise. “A major new voice” and “shockingly good”, pledge the endorsements on her book jacket. She delivers on those promises too.

Naoise is only 27, but her debut novel Exciting Times is being published this week to critical acclaim. The novel at its heart is a love triangle, well worn in literature from Wuthering Heights to the Twilight saga. But if you think you’re already an expert in that romantic geometry, don’t be so sure.

Naoise’s story is of a socialist English teacher, Ava, lost in Hong Kong, and living in the penthouse apartment of the rich banker she’s fucking, Julian. All the while she flirts closer and closer to Edith, the mysterious woman she maybe might love. Her prose is a swirl of class and romantic anxieties bent back on themselves, then pinned to the wall and examined surgically. She writes in the literary style of a generation whose communication is all virtual and textual, and therefore subject to continuous revision and cataloguing in real time. As the author herself explains it: “The level of analysis and responsiveness that’s required on Twitter is probably greater than if you’re just sitting in the pub having pints.” The result is a style that’s anxious yet precise.

Naoise brilliantly twists language around the thread of Ava’s desires and fears, using each English lesson as an expository joke on the protagonist. When investigating the grammar of the subjunctive in her classroom, she teases: “You didn’t say: ‘What if I was attracted to her’. You said: ‘What if I were’.” Naoise toys with linguistics, not just to tease Ava’s romantic awakening, but also to decolonise the text itself as it’s unfolding on the page. Ava’s Irishness and the Hong Kong setting mean the legacy of colonialism is always threading its way through the story, but Naoise rips the stitches out as she goes. It’s refreshing how she drops brazenly specific and politically loaded Irish terms like ‘the eighth’ and ‘Bloody Sunday’ without pausing to explain for an international audience. “I didn’t want to preemptively infantilise the British reader”, she tells me. She pauses and grins mischievously. “Though there’s plenty of justification for doing that”.

The women in the novel signal their queerness not with rings of keys but with sly Insta story views and loaded instant messages. Ava assigns Edith’s Instagram as much intellectual weight as if it were itself a language: “Her posts were like clues; here is some Edith, and some more over here, and an entire Edith somewhere beyond the squares”. Naoise expertly captures the subterranean self-awareness of queerness before it dares to reveal itself, and delivers it all with the irony of the extremely online. You find yourself screaming at the page, wondering why a character who can outthink everyone in the room seems determined not to acknowledge the love in front of them.

“As a queer person, I think you’ve got such an uneven skillset where cognitively you’re very good at discussing relationships — through supporting your straight friends in their various moments of melt — but your own experience is lagging, because of not having your own queer relationships acknowledged”, she says. “In terms of emotional stages, we’re often doing the shit straight people did five years ago, but with a cognitive understanding that’s five years ahead. So I think that’s why we’re so lacerating to ourselves”.

The way Ava’s inner monologue constantly second guesses its own self-deceptions in the novel is not just inspired by the experience of wrestling with latent queerness, but is a reflection of the economic anxiety our generation feels as a whole. Exciting Times is as much a study of the parasitical nature of class as it is of blooming queer desire. When Ava stresses about losing her relationship with Julian, not because she would miss him but because she would no longer be able to stay in his gorgeous apartment, one can’t help the mind tracking to a certain Bong Joon-Ho film. Naoise herself points to this as another motivation for Ava’s racing, self-critical inner monologue.

“For our generation, there’s this material need to be more conscious of the implications of everything we do because we don’t have the security nets the generation above us had. Our survival instincts often don’t know when it is the case that we have those material needs, and when it’s just oat milk vs. almond milk. That same racing cognitive process just attaches in places where it’s not relevant. And that’s how you develop anxiety, kids!” she jokes.

Between writing the novel and having it published, Naoise discovered she was autistic. She says she’s not entirely sure how much of her idiosyncratic style comes from internet culture and economic precarity, and how much just comes from her social masking as an autistic person, constantly having to second guess her social performance to appeal to people. “I didn’t consciously know I was autistic when I wrote the book, so I think a lot of it is just the level of cognition required for me in any human interaction,“ she explains. “I’m a lot more reliant on direct communication, and friends are like ‘Oh, but that feels rude to me’. I’m like, ‘Okay, but the constant passive aggression I have to do to communicate with you feels rude to me!’”.

Where the protagonist of Exciting Times is often deliciously unprincipled, the author herself is steadfast. She committed last year to sail-railing (using only ferries and trains instead of airplanes), in order to combat the outsized carbon footprint of air travel. The only reason I’m able to interview her is because she cancelled her sabbatical in Paris to stay home and vote in the Irish election. “I was always like that with any social issue once I learned about it as a kid,“ she says. “I went vegetarian at eight. This is an aspect of my politics where my autism is really useful to know about. There’s that lack of a filtering mechanism. It’s not something I’d want to pathologise but it’s also not something I’d praise myself for.”

Naoise’s uncompromising ethical stances and witty Twitter-ing mean she’s already becoming a role model for people concerned with climate science and other issues. But how does one stay positive under seemingly endless centre-right political rule? “I’m loath to say ‘let’s all do what we can’, because the way that gets misrepresented by neoliberal politicians is, ‘get a keepcup and everything will be fine’”, she eyerolls. “I think acknowledging the level of cognitive dissonance we all need to live today is important — otherwise we wouldn’t be able to do anything in this hellscape”.

“For example, I find it completely infuriating how much effort I put in to save a relatively small amount of carbon dioxide, when the policymakers who could save a much higher amount through climate justice measures, don’t”, Naoise continues. “But I take that fury and use it, instead of saying ‘fuck it I won’t do anything’”.

“Accepting that something won’t be a complete solution and still doing it, is actually something that can be really politically animating”, she concludes brightly. The optimistic closer feels appropriate. With Naoise Dolan on the literary scene, there are exciting times ahead.

Credits

Photography Donal Talbot