It’s not exactly news to hear that the current Tory government are a threat to the rights and lives of LGBTQ+ people. Last week, the UK’s purportedly-objective Equality and Human Rights Commission was accused by staff of having a culture of transphobia, just after it suggested investigating whether trans people should be included within the long-promised conversion therapy ban. Meanwhile, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recently deemed the UK a country with “extensive and often virulent attacks on the rights of LGBT+ people” in the past few years (Russia, Poland, Hungary and Turkey were also put on this list).

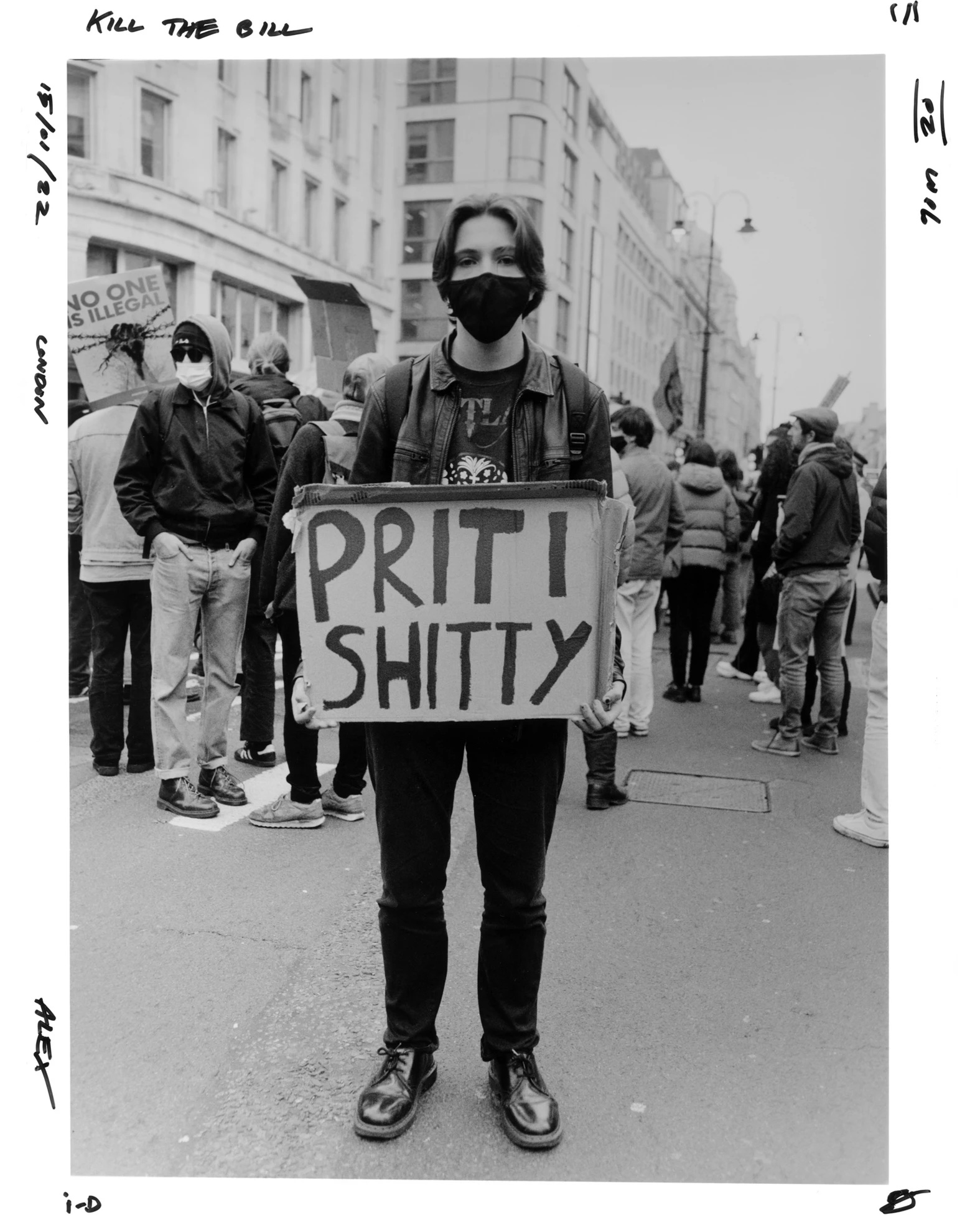

But there are also ways in which the UK government is introducing policies that affect the rights of queer and trans people in more insidious ways. Home Secretary Priti Patel’s Nationality and Borders Bill, currently being debated within the House of Lords, has received much criticism for its racist and cruel policies that could see people stripped of their nationality, creating tiers of citizenship and punishing refugees, despite seeking asylum being a legal right. The UN has expressed concerns that the bill even goes against international law.

For Rainbow Migration, a charity supporting LGBTQ+ people through the UK’s asylum and immigration system, the bill poses a serious threat to those currently in the process of gaining asylum, as well as those who look to seek it in the future. “This bill will make it extremely difficult for any LGBTQ+ person, who’s afraid of being hurt, or possibly even killed in their country of origin, to get long term protection in the UK,” says Leila Zadeh, executive director of the charity.

Rainbow Migration notes a couple of ways in which this bill would put queer and trans refugees in stressful, even dangerous situations, and are currently working to have certain clauses of the bill removed. Of all aspects of the contemptible bill, the section most worrying is Clause 31, which will raise the “standard of proof” needed for people seeking asylum to show they have a characteristic that puts them at risk of persecution within their home country. “With the current ‘standard of proof’ in UK law already in place, many people [seeking asylum] are often disbelieved as is by this government,” Leila says. “How do you prove your sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression or sex characteristics? It’s a very difficult thing to do.”

It’s not clear exactly what evidence the government expect people seeking asylum to provide that proves they are LGBTQ+, but in a letter to the House of Lords, Rainbow Migration has outlined how the increased difficulty may “potentially jeopardise the lives of people who are fleeing homophobic, biphobic and transphobic persecution.” After all, many will be fleeing from countries where they would not be able to begin medically transitioning or get married to prove they are in a same-sex relationship and to attempt to do so might put them in harm’s way. For many LGBTQ+ people, the only evidence they have of their identity is their own personal account.

Rainbow Migration report that under the current system, almost half of Home Office refusals of LGBTQ+ asylum claims are later successfully challenged upon appeal. When the current standard of proof is clearly rather ineffective, already meaning a large number of LGBTQ+ individuals are being disbelieved and left to fend for themselves in dangerous circumstances, increasing the level of proof will only increase the number of people failed by the system.

The bill will also put in place deadlines (the time limit as yet undecided) for when you would need to provide evidence, with anything submitted after this date potentially ignored. “That will cause problems for those whose evidence might be a letter from a partner, former partner or friend in their country of origin,” Leila says. “That can take quite a lot of time to establish contact and ask somebody, particularly an ex, to write a statement confirming you were in a relationship.” There’s also the risk that a person won’t want to provide written evidence out of fear, and Leila says conversations around this can all take quite a while.

“I was one of the lucky ones able to fly out from my country, and even I did not manage to get all my documents that I needed,” says Bahiru, a 36-year-old gay man who was exiled from Ethiopia in 2016. Rainbow Migration helped him seek asylum in the UK at the time and now, he is currently undergoing the process of gaining permanent residency. “There are people who crossed bodies of water or were trafficked over, and we’re expecting them to meet deadlines?” To him, clauses like these in the bill echo a blind spot within the lawmakers about the lives of queer people of colour in particular. “Whoever is writing this is either ignorant of class and race… or they all have heteronormative ways of thinking,” Bahiru adds. It’s probably both.

Bahiru points out that for many people across the world, “to even be suspected of [being LGBTQ+] would destroy the relations you have with your family. Even if you called them once you got to the UK, there is no way they would accommodate your request to send over documents.” Bahiru and fellow exiled Ethiopians have founded House of Guramayle, a digital safe space for queer people from the Horn of Africa.

There are other aspects of the bill that Rainbow Migration argues will seriously affect LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum, even if the dangers don’t seem so obvious in the bill’s wording. The bill will create categories of refugees, and those who don’t claim asylum immediately upon arrival in the country face being considered less credible and therefore placed in a ‘lower-class’ category. “The problem with this is we see many people who don’t know you can get refugee status because you’re LGBTQ+,” Leila points out, stating most people think asylum is for those fleeing war or under threat for political reasons. “Many LGBTQ+ people fleeing persecution will just up and leave or will be already in this country [for example, on a visa], will see things at home have got worse, and then will just stay on here and so won’t claim asylum straight away. Under this bill, they will be put into group two and may only be granted temporary protection.”

That temporary protection they receive is something else that is new under this bill. Currently, people seeking asylum have five years “leave to remain” within the UK before they can apply to settle here permanently. Those in group two with temporary protection will be reassessed within five years whether they would still be persecuted within their home country, and potentially sent back if the Home Office deems it safe. “How can you rebuild your life with the knowledge hanging over your head that in a few years time, they might look at removing you to your country of origin once again?” Leila asks. “People will worry about every action they take. If they start transitioning or enter into a relationship, will that put them more at risk if, in say three years time, the government wants to send them back?” During this period, those in group two will also have restricted access to certain rights such as family reunion, and bringing over partners or children.

There’s also the problem of what the Home Office deems safe. Likely, this will be based on if the legal status of LGBTQ+ people within a country has changed, and if so, people seeking asylum from there might be more likely to be sent back. The problem is that it can take a society much longer to change its perspective, and many LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum would still be at risk back home, even if they are no longer criminals under the law. Clause 28 of the bill also plans to house refugees offshore while their asylum claims are being processed. Though denied by the country, Sky News reported that Ghana was one of the countries being considered for this, a place where same-sex relationships are still criminalised and LGBTQ+ individuals are sometimes targeted by the police. “That would be a terrifying situation for an LGBTQ+ person who’s fled persecution in another country but then finds that the UK government has placed them in Ghana.”

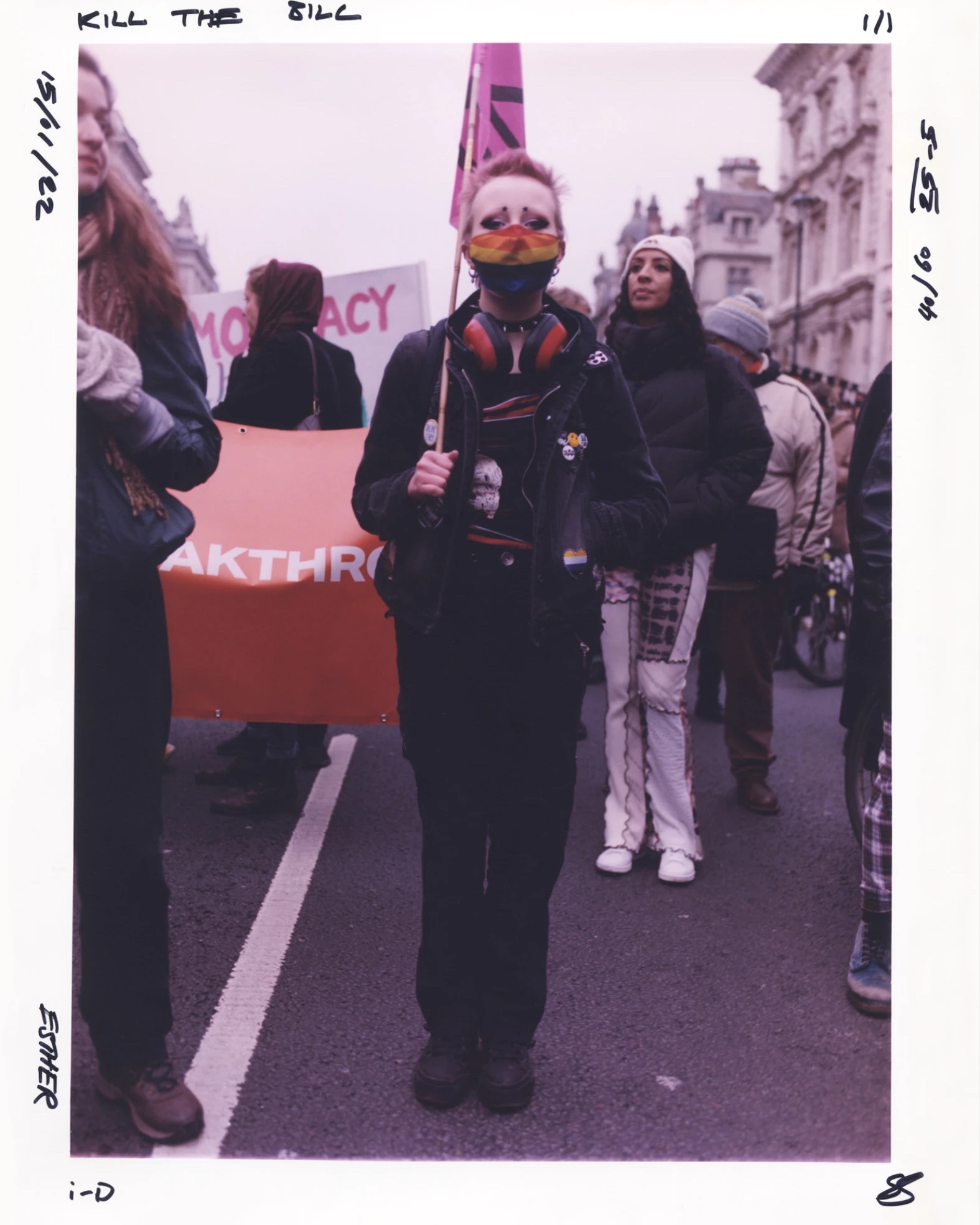

After elements of the equally-fascist Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill were rejected in January by the House of Lords, Rainbow Migration holds out hope that the allies they have within parliament will push back against the Home Office’s bill. For those looking to help, Leila encourages donations to Rainbow Migration and to sign up to their newsletter and follow their social media, where they will be sharing campaign actions. “This bill will mean people will be stuck in the system for far longer than they are now as they fight attempts to remove them to their country of origin,” Leila says. “They’ll continue to live in poverty, and so our work is going to be more crucial than ever.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on politics and the LGBTQ+ community.