So you want to be a fashion designer? Warning: The old roadmap is useless. Runway show first, get stocked in prestigious stores second, then wait for a quorum of important people in superior eyewear to declare you’ve “arrived.” It’s time to fold that into an origami swan and let it drift down the Thames. London Fashion Week just wrapped, Milan’s rolling on, and the once-straight line to success has unraveled into a gorgeous, unruly spaghetti. Or, as Kim Kardashian once tweeted: “They can steal your recipe, but the sauce won’t taste the same.”

Independent designers are no longer asking how to join the system. They’re deciding when (and if) the system is useful. The runway is now just a tool, not a sacrament. Scaling the business to be a global behemoth is optional. Intimacy can be a clever strategy. The new KPIs? Control, cash flow, community. Oh, and clothes people actually want to buy. Duh.

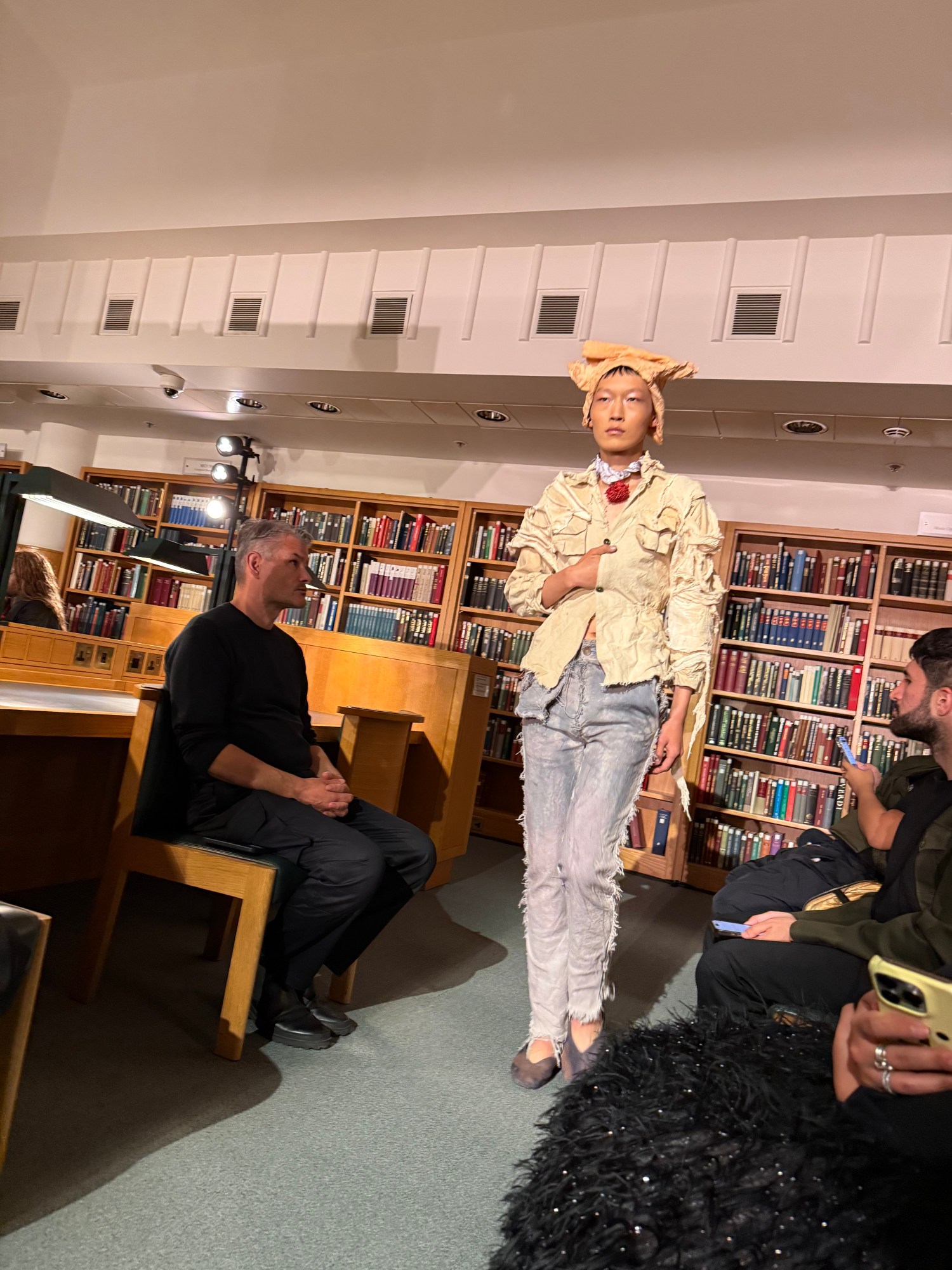

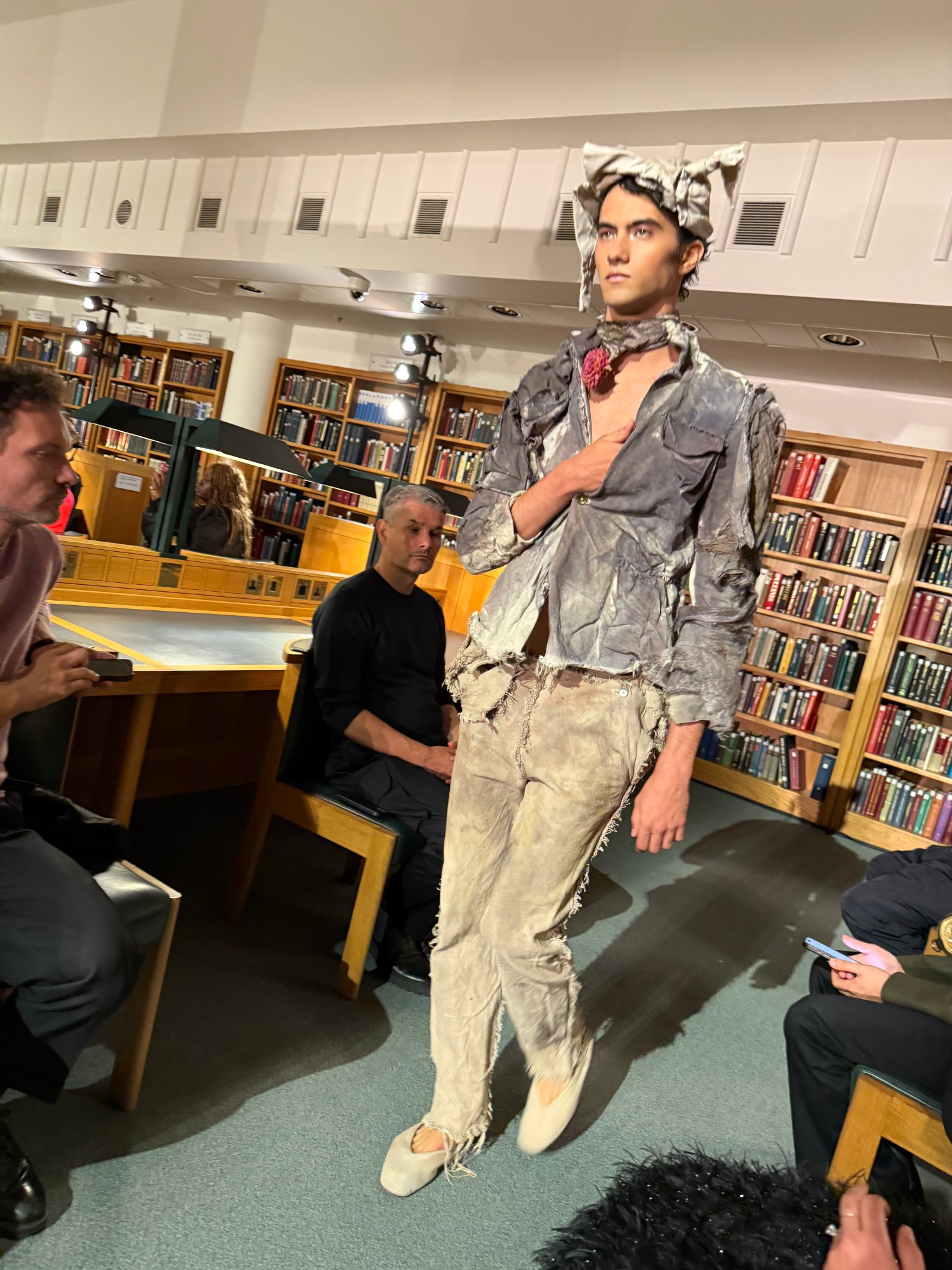

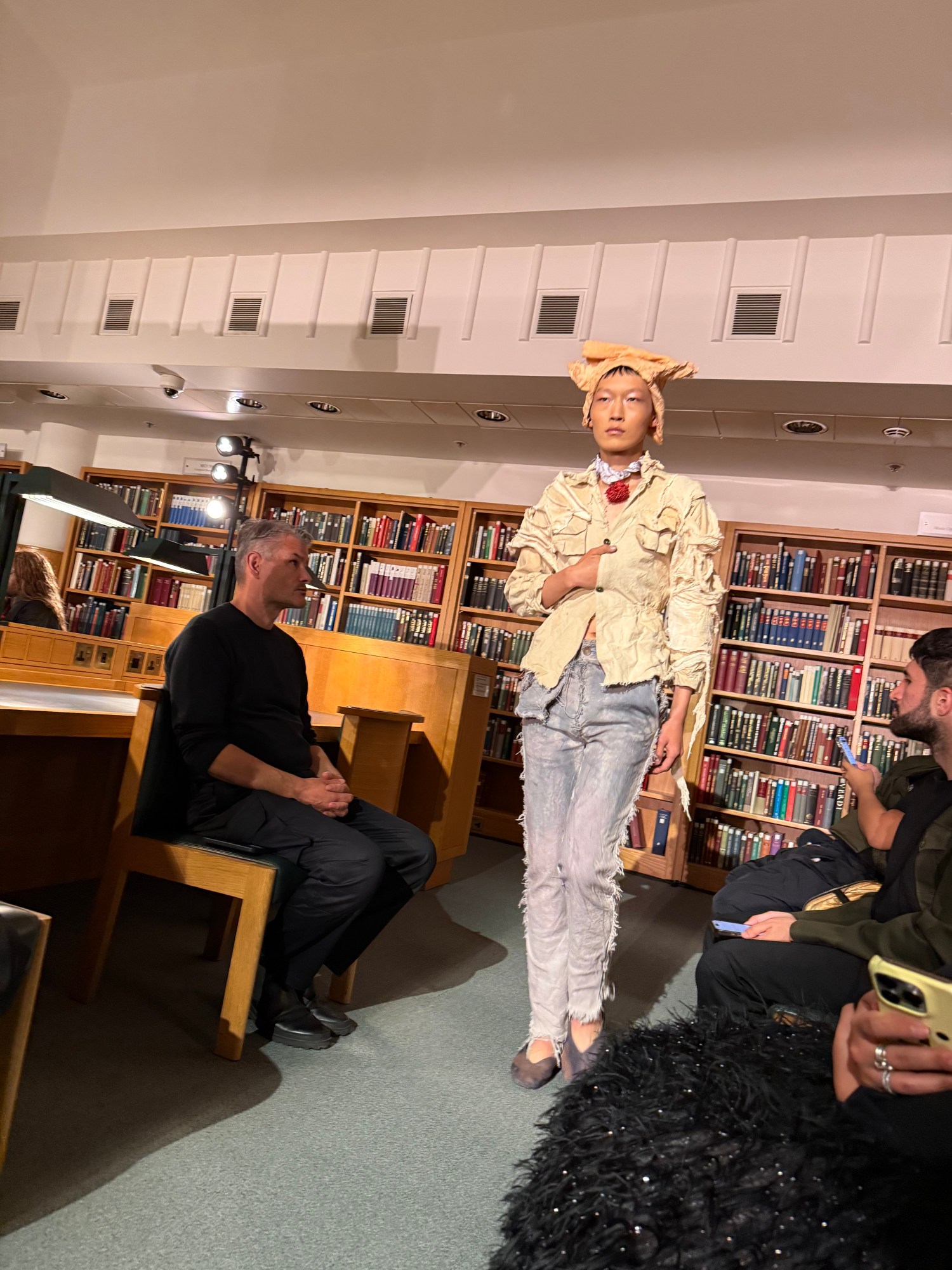

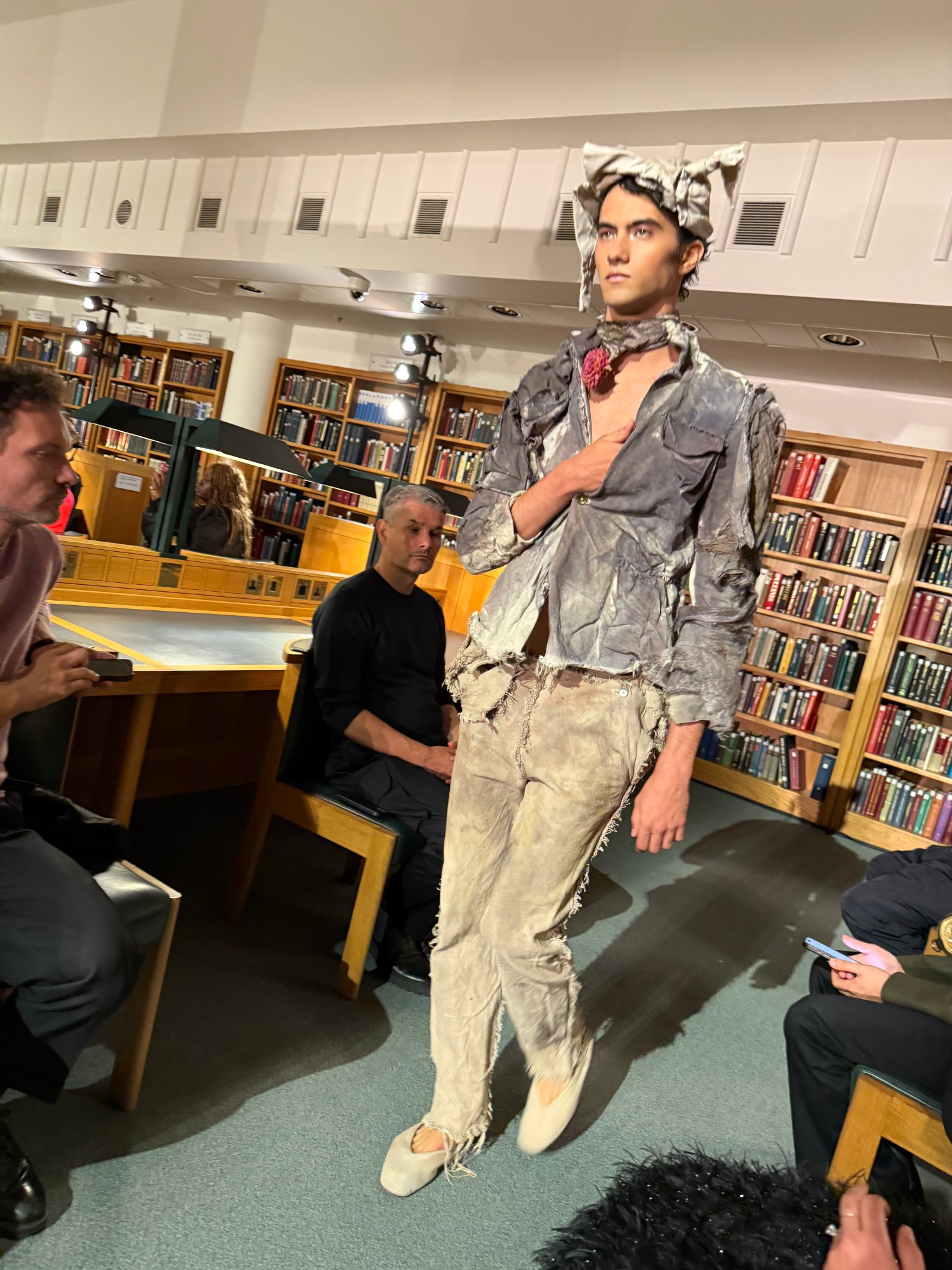

Oscar Ouyang is the tempo shift. He sold his eponymous brand for seasons at Dover Street Market and H.Lorenzo before stepping onto the official London schedule. Why now? “It’s our fourth season, and I’m confident enough to build the team around me,” he tells me at a casting. “Designers always have a story—and an ego—to be heard. Now I feel ready to share the universe.” He refuses the old pressure. “There’s never just one path. Sometimes you don’t need a show. It’s not for everyone.”

That pragmatism echoes in Talia Byre’s slow-burn approach. She didn’t rush into big runway moments; she built a world people could live with for six months at a time. “Most of it was necessity,” she says of salon-scale presentations. She kept to that format for 2 years, until her first show in 2022. “We moved closer to DTC, so we needed enough elevated imagery to last a season. We didn’t have the budget for a massive show, so it was more important to connect.”

And on the supposed treadmill: “Once you start showing, then you feel like you have to every time—that’s the trap. But you really don’t.” If she upshifts, it’s because surprise is a tactic, not a tradition. “You have to keep people on their toes. When you do it, it should feel exciting.” This season, her biggest show yet, the guest list was capped around 80 people by choice: “Tiny for most people, but it makes you work harder. Curated. Who needs to be there?”

Byre’s community-building is grounded and authentic. “It starts from within the studio. How you treat the team—they’re an extension of you. A lot of the people on the press or VIP list already buy from the brand. That feels real.” The moral: Virality isn’t loyalty, proximity isn’t community. Relationships are.

Meanwhile, Jake Burt—co-creative director of Stefan Cooke and the force behind his own label and store, Jake’s—has reverse-engineered the presentation economy. Stefan Cooke paused shows, pivoted to lookbooks and “funny, off-hand events,” and the connection to shoppers and fans got warmer, not weaker. “Shows? Sometimes I love them, sometimes I don’t,” he says. “Lookbooks let us chase the perfect fashion image.”The brand’s Spring 2026 launch at a bookshop with beers and buds spilling out into Cecil Court changed the air: “It relaxes your audience.”

And good vibes switch on the sales brain too: “Can you make a profit, have good cash flow, and do people buy the clothes? Cut out every middleman you possibly can.” His MBA curriculum for new designers is deliciously unromantic: “See how quickly you can sell clothes to people.” Jake’s shop model—ring the doorbell, peruse the rack, have a conversation—delivers both profit and proof of concept. “I watch people try things on. It’s someone deciding whether to spend £500 on a Saturday. Invaluable.”

But of course, he misses the theater. “Shows are weirdly archaic, but I’m addicted to them,” he laughs, remembering the rush of controlling the Stefan Cooke soundtrack. “The music is what I miss most.” His compromise fantasy: “Huge parties every season—fuck a show.”

If all that sounds like missing a little dramaaaaa, Torishéju Dumi restores a sense of cinema, without the dogma. Fresh off the LVMH Savoir-Faire Prize (where she nabbed €200,000), she’s clear-eyed about structure and magic. “Mentorship is imperative,” she says. “I’ve been learning as I go. It helps me think faster.” She’s been a one-woman operation—patterns, production, distribution—so her new funds go first to scaffolding. “A pattern cutter on commission. A technician. I have so many ideas; this helps me work efficiently.”

Cadence, for her, is both creative and financial discipline. “I show once a year,” she says—by necessity and by choice. The off-season becomes focus: “Create a capsule of key pieces—ten jackets and coats—and build a world around that.” As for the runway—she has a show coming up in Paris this season—her stance is clear: “If you intensely feel there’s a message you want to share with the world, do a show. There’s nothing like it. It’s like being a movie director. It inspires people to dream. Shows should never, ever die.” Then the boundary we all need taped above the cutting table: “I’m not going to stress myself. It’s fucking clothes. Life’s too short. I’m breathing and drinking water.”

In Paris, Abra’s Abraham Ortuño Pérez treats the official calendar as recognition, but not a revolution. “Nothing really changed,” he says of moving from off-schedule to on. “It’s amazing to have that validation, but what matters most is control.” And control this season meant rejecting the runway altogether. In a season stacked with debuts—Matthieu Blazy at Chanel, Duran Lantink at Jean Paul Gaultier, Jonathan Anderson’s first womenswear for Dior—he chose a presentation format instead. “The schedule is impossible,” he explains. “I wanted people to actually touch the clothes, see the details—and I have full control of what comes out. I’ve never loved runway images—there’s always something that looks wrong.”

That clear-headedness extends to product. “Offer a product people are dying for,” he says, citing the now-ubiquitous sneaker-ballerina hybrid, born in his studio and quickly imitated by bigger brands. Desire is design, and defensible IP. Nor does he believe every collection requires a stage: “A brand doesn’t have to present every season.” Abra remains deliberately small, a nine-person team split between Madrid and Paris. “We’re a small family company, and that makes me happy.”

Line up their answers and the “new rules” resolve into questions that force clarity:

- Do you actually need a runway right now—or a room, a camera, and the right 80 people? (Talia Byre.)

- Are you designing for a 20-second runway impression or for the Saturday customer in the fitting room? (Jake Burt.)

- Is your show a message you’re finally ready to send, not a ritual you’re told to perform? (Oscar Ouyang.)

- Can you architect a year like a film studio: one big release, one focused side project, one coherent message? (Torishéju.)

- Are you in control of the format, the images, and a hero product that’s distinctly yours? (Abra.)

Underneath, it’s about math and manners. Cash flow over clout. Margins over mythology. Treat your team like your first audience. Build a community that shows up with wallets, not just Wi-Fi. If legacy retail is wobbling (sorry to Ssense) and calendars are congested, the independent answer isn’t to cosplay scale—it’s to right-size ambition to what you can own and what your customer can feel.

Is the runway obsolete? Hardly. London made the counterargument. Simone Rocha, Ashley Williams, Dilara Fındıkoğlu, and Chopova Lowena delivered shows that felt necessary, not perfunctory—statements only a runway could hold. And notably, the city’s most resonant stages belonged to women, a sharp break from the male-dominated musical chairs elsewhere.

What’s changed is literacy. The show is now one dialect in a larger language. Some seasons you orchestrate a symphony; others, you drop a cut-glass EP. Either way, the task is the same. Release something people want to live in. In the end, that’s the only metric that matters.