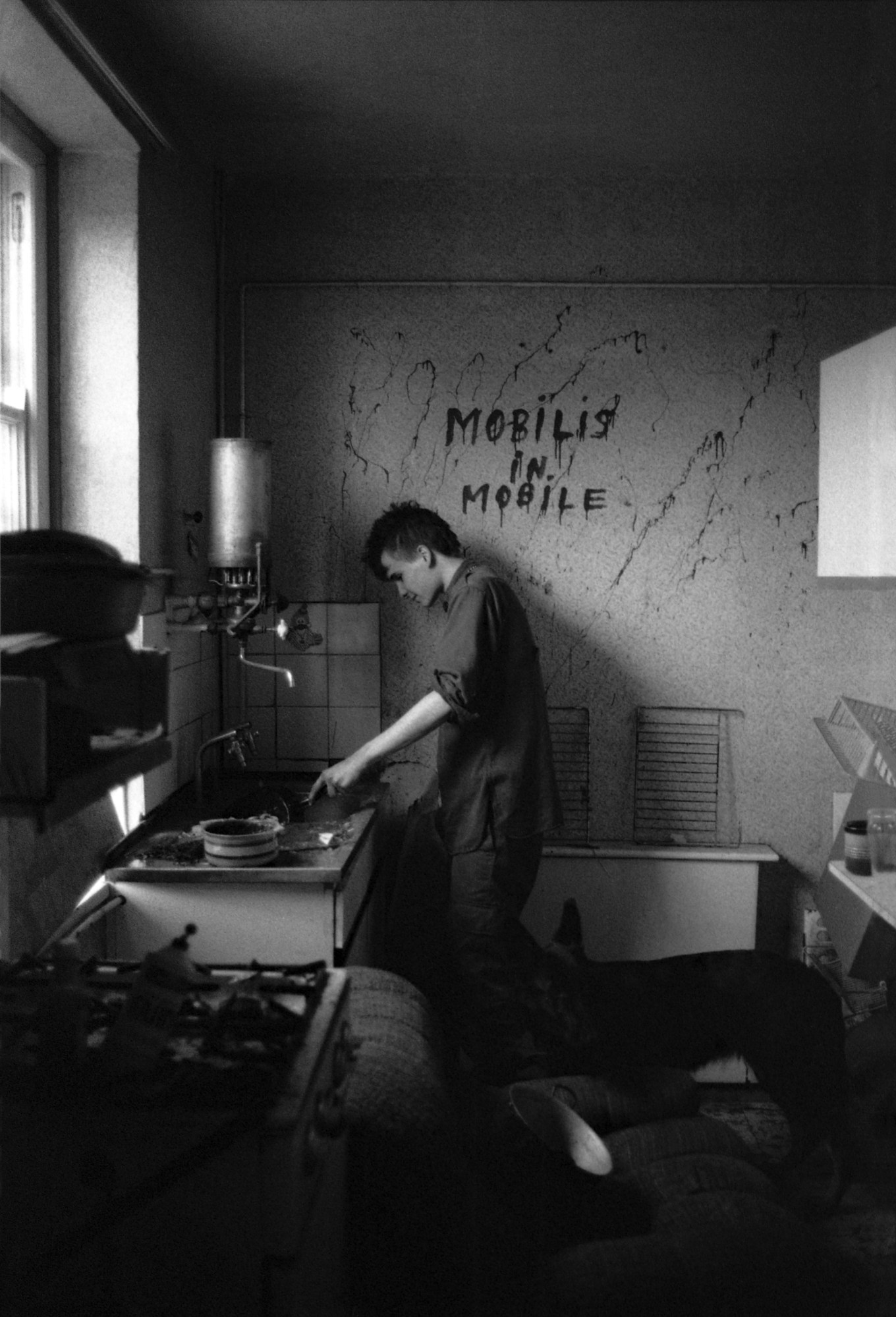

Nick Waplington’s new book, Anaglypta – designed by Jonny Lu Studio –begins with black-and-white photos he made at school and processed and printed in its darkroom. “Often badly developed, these images tell a story of a child looking for something of his own, something to grab hold of and keep close,” he says. “These early photographs defined where the book went next.”

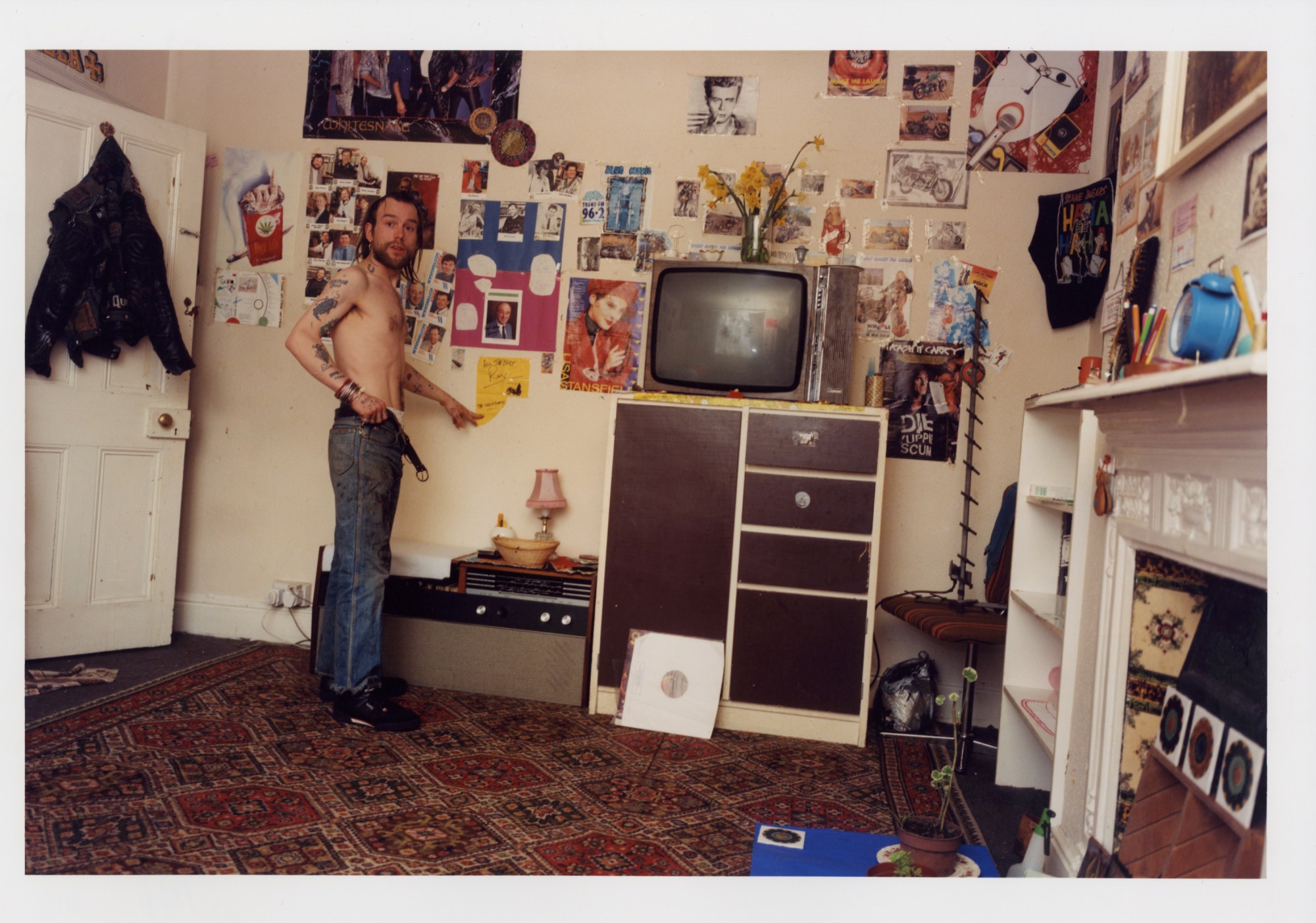

Choosing to stick with images related to protest and music, plus a few self-portrait-based projects, the book meanders through Nick’s archive from the 1980s all the way up to 2020. “These were pictures I took when I wasn’t working on book and exhibition projects — evenings and weekends, out with friends and enjoying life.” Set against a backdrop of unrest and revolt, the threads that tie Britain together across four decades seem unchanging.

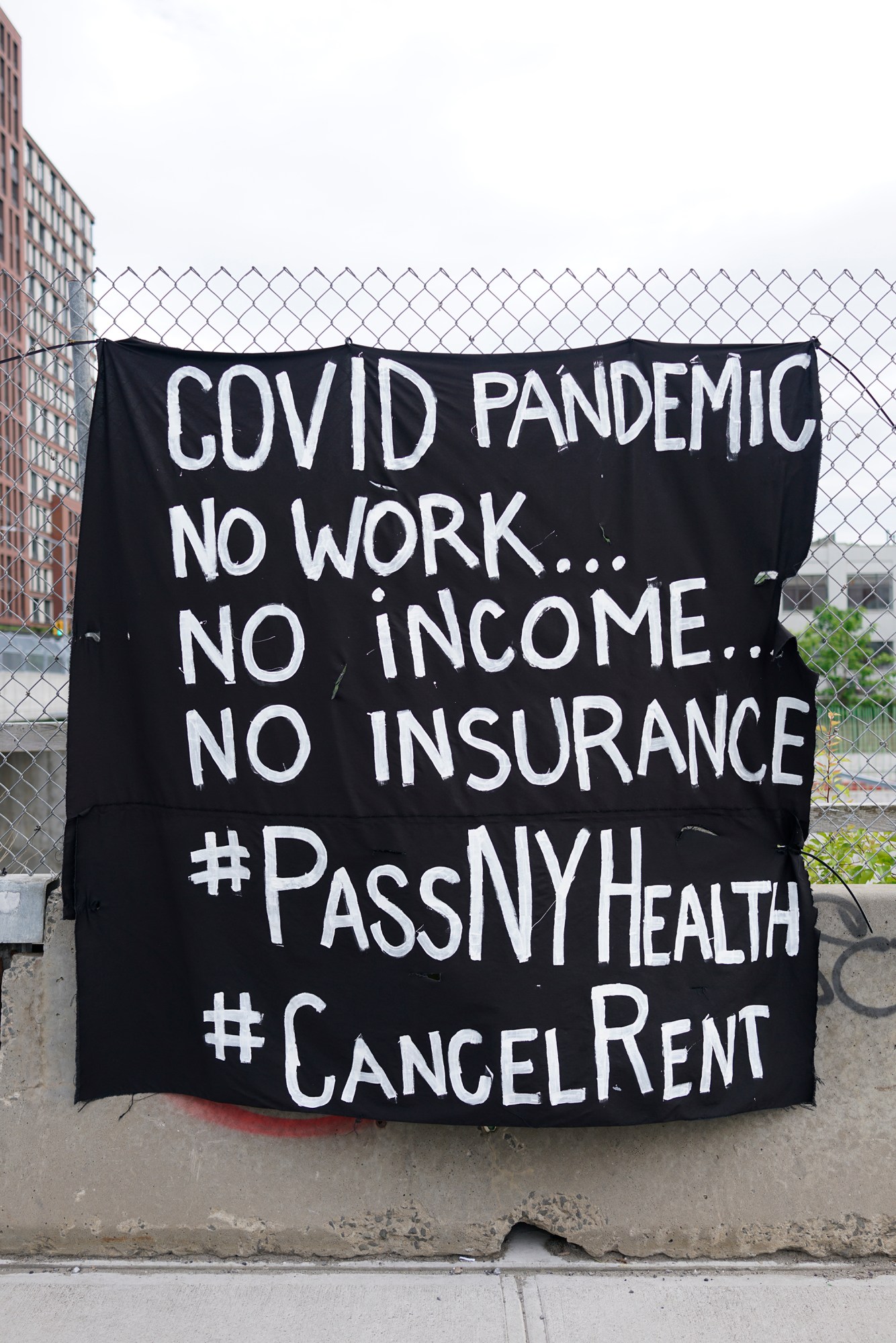

The era of 1980-2020 takes in huge social, political and environmental upheaval – but this shows no sign of slowing down. What compelled you to stop and look back now?

The pandemic provided me with a moment to look beyond my structured photography projects and painting practice and delve into my archive. It occurred to me that we are 40 years from the election of Ronald Reagan and the beginning of Neoliberalism. This form of capitalism has now reached its logical conclusion with the emergence of populist strong men leaders such as Putin and Trump. I know this is simplifying things a little, but it gave me a foundation to look back at my visual diary images from this volatile and expansive period. It gave me a chance to create a work about my existence during this time, or at least part of it as I feel there is the possibility for further volumes dealing with other parts of my life. I now have a very large picture archive to work from, luckily.

1980 was the year i-D was born and underground culture and nightlife thrived. Do you see any signs of a similar creative rebellion in our current, conservative climate?

Well, I see my 15-year-old son on Snapchat seeking out parties and things to do at the weekend against the backdrop of COVID-19 — this is a form of resistance I guess. But we live in frightening times and I really do not see things getting better anytime soon. Like most ordinary people, I feel a sense of futility and helplessness against the extreme wealth which seems intent on destroying humanity’s place on the planet. Maybe the end of mankind would be a good thing for the continued existence of life on the planet. We certainly seem to be heading in that direction. I lay in bed at night wondering why I am still making art, what is the point, but then you’re in the existential territory of wondering what is the point to anything, and I don’t want to go there.

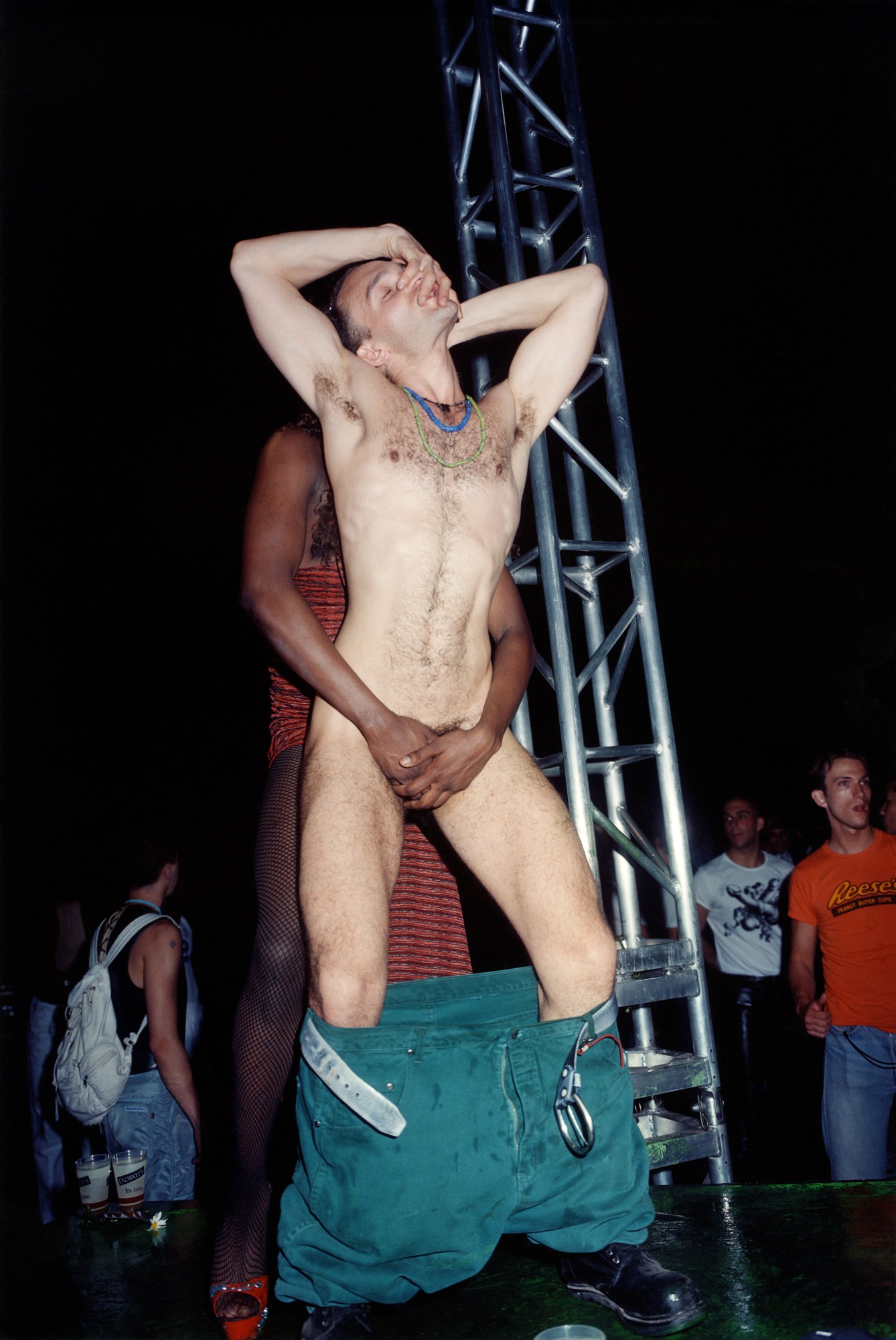

Seana Gavin and Vinca Peterson have also looked back fondly at illegal rave culture of the 90s recently in new published works. It feels particularly pertinent with similar parties in forests and warehouses surging in popularity in the last couple of months. Were you ever consciously documenting it?

I was never an outdoor raves person. I went to a few and took my camera, but as soon as the sun came up I found them very depressing. I liked music in an urban setting. Small dark and sweaty clubs were my thing, places I could go and dance and be back in the studio working in the morning. I especially liked The Milk Bar in London and Save the Robots in New York, these were places full of fun and energy. I’d get on the night bus home and feel elated and ready for the next day.

At the book’s opening you’ve only just picked up a camera and begun shooting. Do you think you’re still motivated by the same impulses now as you were then?

I haven’t lost my wonderment and sense of fun with art. Every day is still exciting to me and I am always looking forward to the next day’s work. I will always take a camera with me on my travels of course. It is a joy of a life for sure and I don’t take it for granted. Even if no one ever sees what I am making again I don’t care — I will just carry on.

Beyond the equipment and budgets, what’s changed most about your photography?

In general terms social media and the emergence of identity politics has brought massive changes to everyone’s practice, even mine. I’ve got an Instagram, and have published a few small zines — but at the same time I’ve been painting every day, which is a kind of slow process that works against the instantaneous social media environment, you can see my paintings on my Instagram. I recently completed a studio based project The Cave which combined my photography and painting. The modus operandi that has always worked best for me is to start a work without knowing where it’s going. From that moment of chance comes rigour as I develop things both conceptually and materially and hopefully I will end up with new work that pushes my practice forward.

And finally, the name?

Lucky Jim, who is near the beginning of the book, liked to stare at the geometric patterns of Anaglypta ceilings when he was tripping off the solvent in glue.

‘Anaglypta 1980-2020’ by Nick Waplington is made up of 512 previously unpublished photographs, made over three continents and four decades. Purchase via Jesus Blue.

Credits

All images courtesy Nick Waplington/Jesus Blue