Since 8 October, the streets of cities and towns across Nigeria have been filled with young protesters demanding the abolition of the Nigerian police force’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) unit. An undercover force first formed in 1992 with the purpose of tackling rising cases of violent crime — including armed robbery, kidnapping, cultism and other forms of domestic terrorism — in recent times, the group has come to resemble the criminals they were set up to fight.

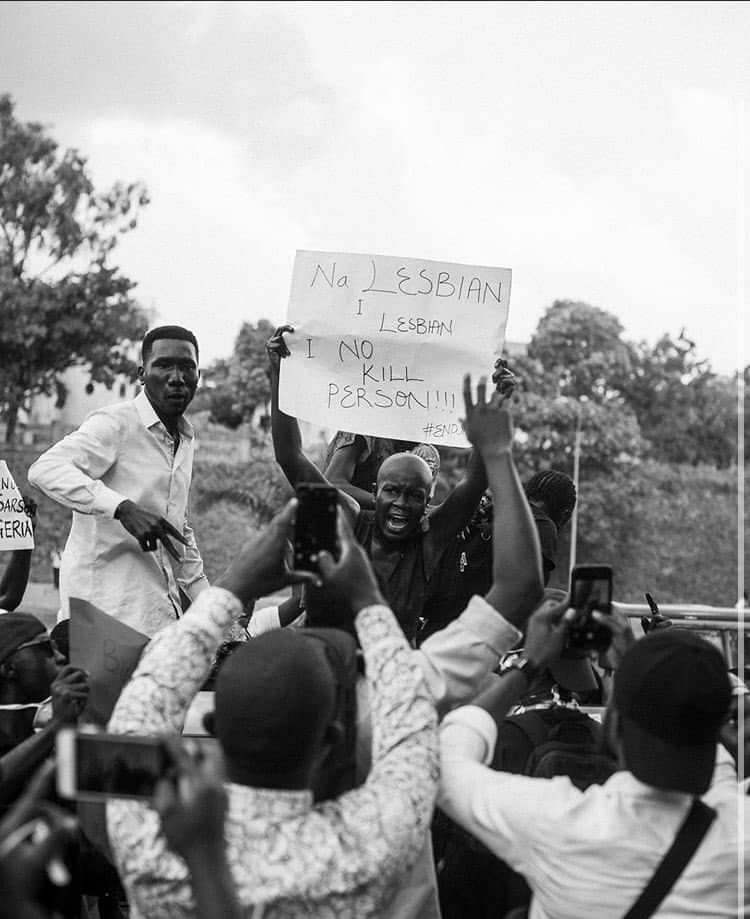

In what is being heralded as one of the most culturally impactful movements in the country’s recent history, Nigerians have mobilised in their hundreds calling for an end to the indiscriminate violence, extortion, arrest, torture and, in the most serious cases, extrajudicial killings they’ve been subject to at the hands of the unit’s members. The overwhelming majority of victims of these crimes have been the nation’s youth, who report reasons for being targetted by SARS officers as absurd as dressing fashionably — sporting dreads or dyed hair, for example — or using an iPhone. Within this demographic, members of Nigeria’s LGBTQ+ community have been especially singled out, often simply for ‘appearing queer’, or expressing a gender identity or presentation not in line with heteronormative social expectation. Still, despite the disproportionate systemic brutality queer Nigerians continue to face, their calls for fellow protesters to recognise their struggle and amplify their voices are largely falling on deaf ears.

Though President Muhammadu Buhari’s announcement on Sunday of his intention to disband SARS, the protests are continuing in response to further injustices. Just three days ago in Lagos, police officers opened fire on peaceful protesters with one person losing their life and many more reported injured. In Abuja, the country’s capital, protesters were met with tear gas attacks and hose-downs. Indeed, these are just new additions to the long list of reports of young Nigerians experiencing brutality from the police force that’s supposed to protect them. According to Amnesty International, 82 cases of police brutality were documented between 2017 and 2020, a figure that only accounts for reported incidents.

It bears noting that Nigerian queer folks aren’t afforded the luxury of reporting crimes perpetrated against them in the first place, due to apathy on the part of the Nigerian police and their enablement of queer-targeted violence. At the height of the protests, a video of a young Nigerian man wagging a finger at a camera and chanting “Queer Lives Matter” began to circulate on Twitter. The video, shot on an open street in Lagos, has since garnered over 10 million views and more than 40k likes. Impressive as its engagement tally may be, what’s more important is the signal that the chant by human rights activist Matthew Blaise sends to fellow #EndSARS protesters, who remain oblivious to the particular ways in which SARS has oppressed members of the Nigerian LGBTQ+ community.

The unit’s actions are, shockingly, legally vindicated. In 2014, the federal government of Nigeria passed the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, a law that not only stops Nigerian LGBTQ+ folks from marrying, but also criminalises the gathering of and affiliation with queer individuals. The result has been an unending wave of institutionalised homophobia, which occasionally manifests in violence.

According to a 2019 survey conducted by The Initiative For Human Rights (TIERs), an NGO dedicated to fighting on the behalf of members of socially marginalised communities, up to 330 human rights violations were reported based on real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. In 2018, 57 young men were arrested at a birthday party, accused of organising a homosexuality initiation event. Two years later and the lives of these men have been irrevocably ruined after being paraded on national television, and they are yet to be acquitted. Despite these grave injustices — including staged sting operations, unsuspecting gay men and women are lured into meeting police officers on dating apps and subsequently attacked or extorted — many often feel unable to report cases of police brutality for fear of further abuse. In 2019, a high-ranking policewoman even made a public announcement telling queer-identifying Nigerians to leave the country or face prosecution.

“As a queer woman in Nigeria, I am targeted by SARS for so many different reasons,” says Uyaiedu Ikpe-Etim, a writer and filmmaker who has attended the protests and openly campaigned as a queer woman against the judicial targeting of queer Nigerians. “I’m sexually harassed almost any night I go out with my friends. My friends who are masculine-presenting women or feminine-presenting men are easy targets, and I’ve had to either witness this firsthand or listen to these stories helplessly. When I go out to protest, it is because of these experiences that are unique to us as queer people.”

For many, protesting alongside other queer women and men provided a rare sense of community. “We were all happy to see each other because everyone likes to pretend we are invisible, but look at us, marching for a country that will fuck us over in an instant!” says Mariam Sule, a writer and entrepreneur.

The invisibility Mariam speaks of remains an issue, with many insisting that there’s a single face to the oppression being rallied against, despite the sizeable number of queer people openly participating in the #EndSARS protest. It’s one that’s male, occasionally female, straight and cisgender. It’s a narrow perspective that excludes marginalised voices from the movement and has resulted in homophobic Nigerians shunning queer voices who speak out online.

“With the buzz [the video] made online, it revealed that there is still a lot of homophobia [in Nigeria]. There were people saying, ‘This is not what the protest is for’ and ‘We are here for #EndSARS not Queer Lives Matter’,” says Timinipre Cole, a lawyer, writer and queer protester. “It made me realise that probably half of the people I protested with would not have been out to protest if SARS targeted just queer folks, it wouldn’t have been their problem. ”

Just yesterday, another queer woman named Amara posted a video on Twitter explaining how other protesters stopped her and her friends from protesting in Abuja. Their placards were torn up and they even experienced physical abuse before another group of other protesters intervened to protect them. While her post has been met with support from fellow queer people and allies, a handful of Nigerians continue to insist that specifying the police brutality on queer Nigerians amounts to a plot to hijack the movement.

Still, Matthew Blaise, who started the #Queerlivesmatter hashtag, using it alongside the #EndSARS hashtag in his video, sees the heightened profile of the plight of queer Nigerians as a step in the right direction towards change, as well as a reminder that queer Nigerians exist and are resilient in their fight for equality. “I feel that a lot of Nigerians know how police brutality affects queer people, but because they are not directly affected or they don’t know any queer person that is affected, they tend to ignore and not talk about it,” they say.

“Now they see people putting their lives at risk to talk about this, we are able to create more awareness around our troubles, while reminding the government that we exist and that the laws put in place to govern queer lives are not okay.” As young Nigerians continue to take to the streets in their fight for justice and meaningful action from their lawmakers, the country’s queer community are ensuring that their voices are heard.