The last 11 months have been incredibly hard and isolating for so many of us. Though few would need convincing of this fact, a survey conducted by YoungMinds at the end of last year found a staggering 67% of people aged 13 to 25 felt the pandemic will have a long-term negative effect on their mental health.

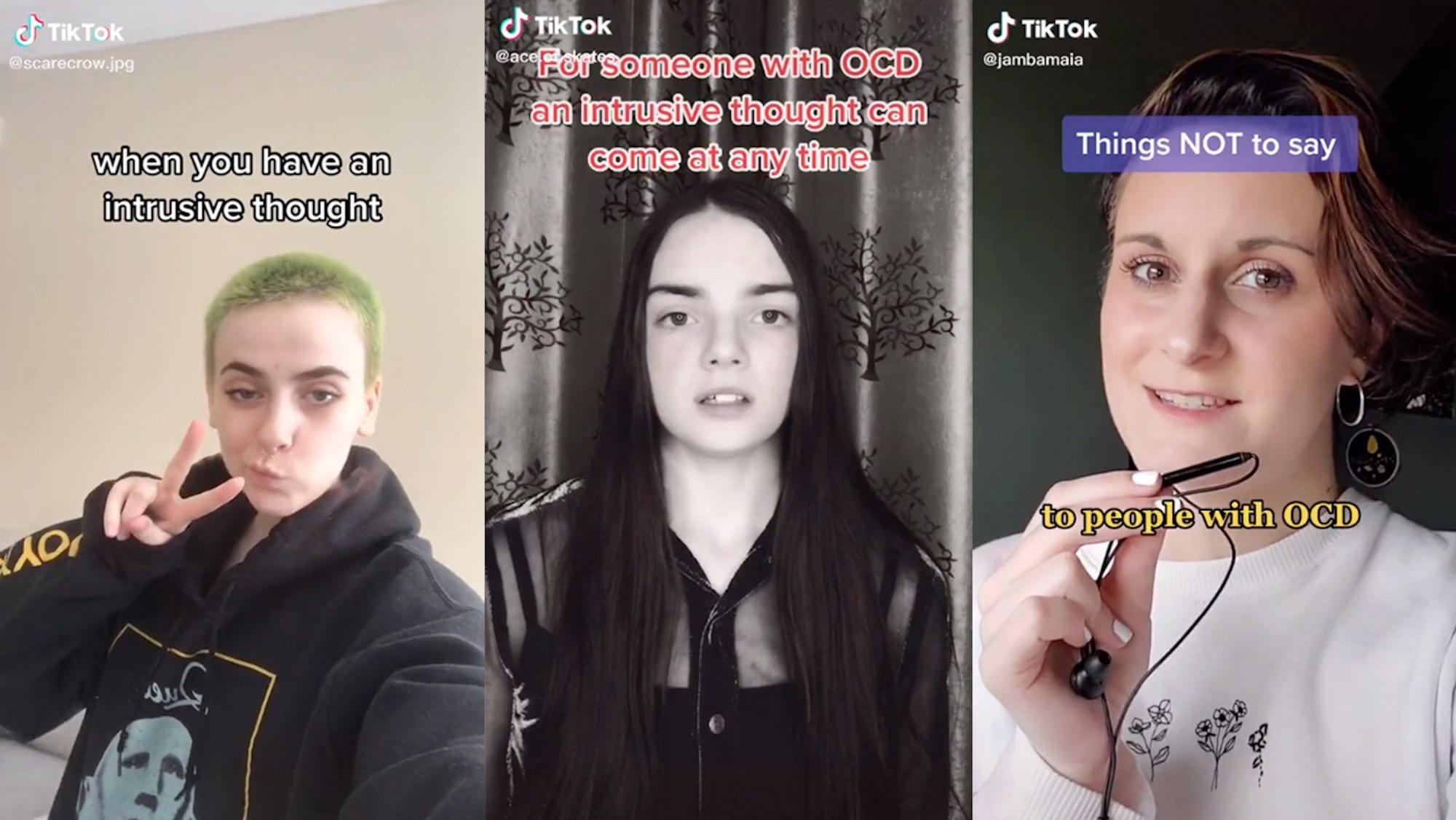

Throughout lockdown, discussions about mental health have become a central feature on TikTok, with many, including therapists, gravitating to the platform to find and offer support and solidarity with those trying to cope with symptoms made worse by isolation. This is particularly true for those of us living with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). At the time of writing, TikTok’s #OCD hashtag stands at around 650 million views.

Everyone knows it by name, but there are so many common misconceptions about OCD. It’s become shorthand for describing someone who is tidy, clean or well organised. Anyone who watched the high school musical drama Glee in the late 2010s might remember teacher Emma Pillsbury, who regularly performed her cleanliness compulsions — such as cleaning her food — with a large smile across her face. More recently, celebrities have self-diagnosed as having OCD, like Khloe Kardashian, who refers to her cleanliness as ‘KHLO-CD’. The reality is, of course, far more complex than these depictions. Defined by the NHS as “a mental health condition where you have recurring thoughts and repetitive behaviours that you cannot control,” for many with OCD, there is actually no fixation with cleanliness, or any outward sign of suffering. Instead, it is a daily battle inside one’s head.

Ainslie, an 18-year-old better known on TikTok as @ace.of.skates, first started talking about OCD in her videos in April of last year, around the beginning of the first lockdown. She wanted to give people a glimpse into what it is like to live with the condition each day, and dispel some of the myths and misunderstandings around it. “The term ‘OCD’ is often taken completely out of context,” she says. “People are always saying, ‘I’m so OCD!’ or ‘I’m a little OCD today’.”

For Ainslie, her OCD manifests in feeling a need to complete a series of compulsions before she can start her day, all of which she details in her most-watched TikTok video. Before she gets out of bed she must blink, rub her eyes and then her eyebrows eight times each. Sitting on the edge of the bed, she then taps each foot onto the floor, before stomping on the ground a further eight times. Finally, she must clench and unclench her fists and stroke her cat before she can start her day. These repetitive behaviours – the ‘compulsive’ aspect of the anxiety disorder, are repeated until Ainslie feels she has done it ‘right’, often taking up to half an hour a day.

Compulsions like this are performed in order to temporarily relieve or neutralise unpleasant feelings of dread and panic. This could be counting, hand-washing, cleaning, tapping or needing reassurance. But many people’s obsessions involve the presence of unwanted thoughts, images or memories that immediately trigger anxiety. Fear of contamination, as we well know, is one, but many are plagued by a fear of hurting someone, or themselves, or the existence of unwanted sexual or violent thoughts in their mind.

These are actually entirely normal thoughts that run, in various forms, through the minds of everyone. The difference with OCD sufferers is that a particular thought, one that provokes an overwhelming sense of anxiety, will play on a loop, like the brain is stuck. The compulsions temporarily stop the loop, but in the long run they actually intensify the anxiety, making the obsessions worse.

Maia Kinney-Petrucha, 25, from New York, is a self-described “intrusive thot”, who was diagnosed with severe OCD at four years old. “All my life I struggled to find ways of explaining what was going on in my head,” she says. “It wasn’t until I found other folks who suffered with OCD that I became more open to talking about my experience.” The pandemic inspired Maia to start creating content in a similar vein to Ainslie via her TikTok @jambamaia, in order to dispel some of the common mistakes people make about the condition. “I knew people like me must have been struggling, because suddenly there was a very real contamination threat,” she says. “I started with one simple TikTok about the misconceptions of what OCD is and it got a lot of traction.”

My own OCD centres around a fear of bad things happening to those who I love, so COVID has really exacerbated my worries, and the extra time at home has increased how long I am stuck in patterns of negative thinking and behaviour. Watching people on TikTok speak so candidly about their experiences, feels like a weight has been lifted off my shoulders. I no longer feel as alone or as burdened by shame. This has allowed me to seek professional help after hiding my OCD for 15 years.

Clinical psychologist and OCD specialist, Dr Tatyana Mestechkina, believes that these kinds of online communities can be extremely valuable. “When people are open about their experiences, they can start to accept their condition and work on overcoming shame,” she says. “These online spaces can allow people to feel validated, understood and less alone.”

However, TikTok videos about mental health issues do have the potential to be harmful. “It can perpetuate misinformation, minimise the condition, and trigger others with OCD, even becoming a source of unhelpful reassurance which can exacerbate OCD symptoms,” she says. “There is also a risk that people may turn to these videos as a way of compulsively checking their progress against others, which can further fuel the condition.”

The #OCD thread certainly has the capacity to platform inaccurate and misleading content. One particularly successful thread of videos sees users line up aesthetically pleasing items in a perfect row, or hoover perfect vacuum lines into the carpet, or colour coordinate their food, and caption them ‘cured’ in relation to supposed OCD. “OCD is not an adjective,’ Dr Mestechkina warns. “If people misuse it in TikTok videos to refer to tendencies of being clean or organised, it can be very invalidating to people who experience great pain from it.”

OCD specialist Dr Lauren McMeikan believes TikTok has the ability to bring levity and humour to a very challenging subject, but has noticed a spread of misinformation about OCD across social media platforms. “I’ve seen uncredentialed OCD coaches tout ‘cures’ for OCD and, even recently, someone suggested that heavy metals can cause OCD. Unfortunately, anyone can get a following, even if they aren’t qualified.”

It is crucial to be aware that TikTok users are rarely trained experts. No matter how relatable their content, it is particularly important to be wary about taking advice–in regard to medication and therapy–as professional expertise will always be the most valuable.

Ultimately the best spaces for these discussions, whether on TikTok or other platforms, are ones that are moderated by someone who has expertise in OCD. Dr McMeikan advises to be aware that TikTok – or any social media – is not a stand-alone resource. She suggests it is used in conjunction with other recovery support like books, articles by specialists, support groups and therapy. For me, seeing that there are others out there who really understand what I’m going through has helped me feel less alone. Alongside professional help, a virtual OCD community has been an important step towards finding the courage to tell my friends and family what I have been going through.