In the early 90s, Studio Ghibli did an experiment – it put together some of its young animators, all in their twenties and thirties, and gave them a chance to make a film all on their own, quickly, cheaply and with quality. Ultimately the project went over budget and over schedule, eventually airing on local television in 1993 and failing to make much of an impact. Until its US release in 2016, it was a rare film for Ghibli aficionados only. The experiment wasn’t repeated, but what resulted from it was Ocean Waves, the queer film Ghibli didn’t know they were making.

As the first film not directed by the studio’s founders, Ocean Waves eschewed the whimsy that was starting to define Ghibli for a more grounded slice of life character drama. As the most modest and least celebrated of the studio’s works, this film explores the love triangle between two teenage boys, best friends Taku and Yutaka, and new girl Rikako. But watching the film, many contemporary and modern fans began to think that were was more than just friendship between the two boys.

Over the course of the film Yutaka and Taku seem to be more interested in each other than in Ocean Waves’s love interest Rikako, who is portrayed as bratty, ambitious and roundly disliked. While Taku appears to keep his distance to Rikako, he values Yutaka over anything else in his animated world. All it takes is for Yutaka to call Taku at work asking him to meet him once his shift is over for him to drop everything and run to his friend: “I just wanted to see you” is all he needs to hear. “I always thought of Yutaka a bit different than my other friends,” Taku admits to himself, and when Yutaka falls in love with this new girl, his feelings of jealousy are very clear: “I felt unreasonably irritated to know that Yutaka was interested in Rikako, I thought she’d never see his real value.”

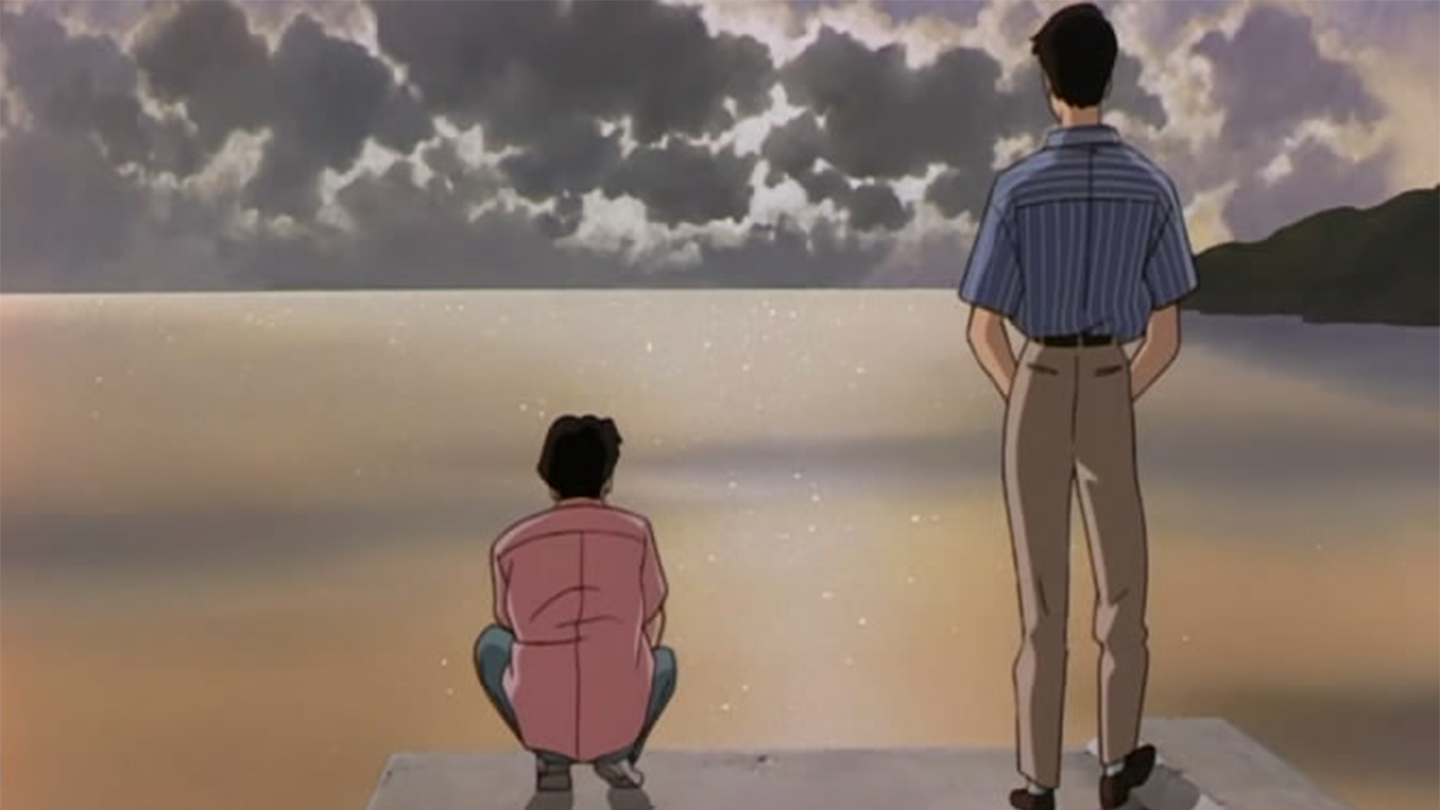

Halfway through the film things get dramatic real quick: after a physical fight over Rikako, the boys fall out, and ultimately never speak again until years later during the highschool reunion that frames the entire film. The pair, now grown adults, meet up and drive around town together, catching up on lost time and reminiscing on where their lives have diverged. The sun is setting, a slow and romantic synth music is playing, the both of them staring into the ocean. “I was angry at the time because I knew you were holding back on my account,” says Yutaka. “I hadn’t noticed until that moment,” he continues, “that you really liked Rikako.”

Unsurprisingly, given the heavy queer undertones of the film, most Ocean Waves fan dislike this decidedly hetero ending. While it was the expected path for cinema, particularly Japanese cinema, in the heteronormative 90s — the film first aired all the way back in 1993 — fans and critics bristled against the ending, and the experiment itself, and even 27 years later, out of all 22 studio Ghibli movies, it’s consistently ranked as one of the worst. Empire puts Ocean Waves at number 22, The New York Times and WIRED at number 20, The Guardian at number 15, and GQ doesn’t consider it at all. Some of the harsher critics called both the characters and the animation lifeless and the film as a whole not especially memorable. With a runtime of just over an hour, the story-telling does feel disjointed at times, with an editing style that much more resembles the jump cuts of a YouTube video than a Studio Ghibli classic, and way too many flashback scenes used for exposition.

The film’s redeeming feature then, is its coded portrayal of a gay character in 90s Japan, and if only Ghibli had embraced Taku’s queerness with open arms, Ocean Waves could have been a banger. But modern fans are attempting to rectify this missed opportunity. In a recent video essay, Youtube user Eliquorice attempts to rewrite history, improving the film retrospectively embracing its queerness. While the vlogger thinks we might mostly be reading into some of the small details, the queerness is imbued into the fabric of the film and in Taku’s personality. “It feels a bit too obvious at times”, Eliquorice says over the phone. “In fact, you only need to really change one thing to make the film work.”

The whole movie is framed by two scenes where Taku sees Rikako at the other end of a train station in Tokyo: at the start of the film he seems startled to see this girl he remembers from his youth and lets her go, while at the end he chases her to profess his love for her. Just flipping the two scenes around, Eliquorice suggests, (and changing Yutaka’s line at the pier that would allow Taku to come our) is all we need to do to turn Ocean Waves into the openly queer film it feels meant to be.

“I think it’s fascinating how you can take the exact same variables and tell a relatively separate and different story,” says Eliquorice. “Every time you are watching something you are automatically doing that, you are putting your interpretation into it. You sort of take it and make it your own thing. There is a point where I feel it doesn’t really matter if this is what the filmmakers wanted to do or not because it’s what came out of it anyway.”

Whether or not Ghibli had planned for Ocean Waves to be seen as a queer film is only speculation. The film they actually made tries to squeeze together a romance in the last 15 minutes. The film that could have been, though, is a daring story of a young boy coming to terms with his feelings and his past, as well as a studio taking a chance on young and ambitious filmmakers to tell the kind of stories that mattered to them and their generation.

Whichever way you see it though, the main theme of Ocean Waves remains the same: it’s all about nostalgia. It’s clear how this team of young animators wanted to make a film that resonated with them and the time of their lives they were in. As they were saying goodbye to their childhood, so did their characters. They are looking back at a time where everything that happens to us seems so meaningful and intense and we feel a lot of turbulent emotions pulling us in all different directions, like ocean waves. But even if it wasn’t meant to be an example of LGBT cinema, the fact that queer audiences see themselves and their teenage years in Ocean Waves is enough to make it a queer film all on its own.