Born in Dakar in 1980, Omar Victor Diop went to business school in Paris before moving back to his native Senegal to work as a consultant. He swapped finance for art after his photo series “Le Futur du Beau (The Future of Beauty),” featuring portraits of women in eco-conscious pleated paper capes and water bottle skirts, drew attention at the Rencontres de Bamako in 2011.

His artistic endeavors snowballed from there. For “Project Diaspora” (2014), Diop created a set of portraits inspired by centuries of notable African figures omitted from historical discourse. Based on original engravings and paintings, Diop posed as each selected man, festooning himself with soccer-related accessories to tie in racism past and present. In an earlier series from 2013, collaborating with photographer Antoine Tempé, he re-envisioned movies including Frida, American Beauty, and The Matrix with black protagonists.

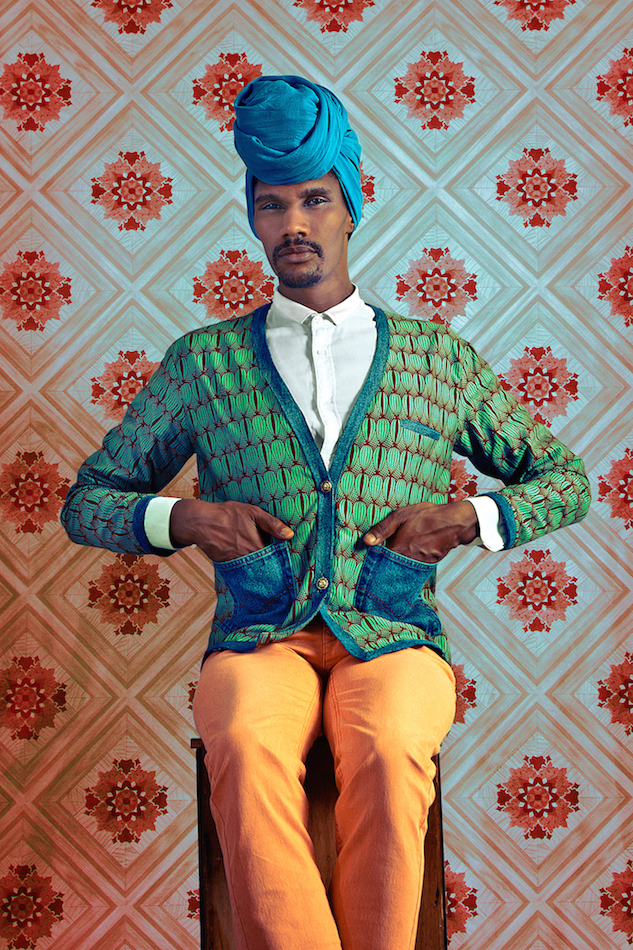

Diop’s latest body of work, “The Studio of Vanities: Staged Portraits of Africa’s Contemporary Urban Scene,” depicts a new generation of African creatives: designers, makeup artists, singers, and ambitious multi-hyphenates. It’s currently on view at Galerie du Jour in Paris, shown alongside black-and-white portraits by iconic studio photographer Malick Sidibé.

What does it mean to share an exhibition with Malick Sidibé?

I was really, really humbled by [the gallerists’] decision to show my work with Malick’s. It’s like showing with Cartier-Bresson or Avedon. He’s had a tremendous influence on photographers of my generation – not only African. I think the first photographer I ever knew was Mama Casset, who photographed my grandfather. We still have her portraits of him in the living room. Being shown with Malick Sidibé is a sort of recognition – but it also adds, let’s say, “positive pressure,” because now I feel I have the responsibility to keep up with the work that he has done.

Judging by the backdrops in “The Studio of Vanities,” you must have an incredible archive of textiles.

My mom has a huge collection, and some of them are more than a hundred years old. They’re passed on from one generation to another. Each fabric in a family is woven for special occasions; those in the family know what it means. So it’s a way for me to give some context to every portrait. Just like colors, patterns can communicate emotions, and an idea of sharpness or poetry or romanticism.

You’ve shown “Diaspora” around the world. How has it been received internationally?

It’s always very unpredictable. When I decided to show the series, I expected it to be huge in the black community of America and Africa, but I wasn’t expecting any interest in Europe because, for a sensitive person, it can look and feel like an accusation. But it’s funny: the reception in France was sometimes even more positive than anywhere else. People really understood what it was about, and people took it as what it was: a contribution to history. I’m not really blaming Europe for the fact that these historical figures that I’m showing were left out; it’s just a fact. Europeans of every generation were fascinated by the stories, and it was a shame that we missed out on them.

What research was involved in that project?

When it comes to facts, the whiter your audience is, the more you need to make sure that whatever you put out there makes sense [laughs]. You don’t want to be destroyed on CNN. It took me about eight months of research to come up with the list of figures that I wanted to pay homage to and celebrate.

“[re-] Mixing Hollywood” also seems like a quest to address the lack of black visibility – but in pop culture.

Since photographer Antoine Tempé and I both love cinema, we thought: how about celebrating the best movies we’ve seen? We had fun throughout the exercise – recreating Breakfast at Tiffany’s in Dakar was great. Later, I did an interview on CNN and one question was about this series. A week after I saw this headline: “Senegalese artists” – and Antoine is American and white, but that was the title – “reinvent Hollywood in black.” Imagine that in the context of Trayvon Martin. The comments section was a war. It was picked up by other international news. It got more and more sensational. Meanwhile, I never had a backlash for “Diaspora,” which is a lot more sensitive because it talks about slavery.

What are you working on currently?

Between April and July, I’ll be in an artist residency in Brooklyn, at Pioneer Works, where I’ll have an open studio during the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair. I’m really attracted to collage, and I think this will be the occasion.

How would you describe your evolution as a photographer?

One thing that I’ve learned is that self-censorship is the biggest threat. The projects that had the biggest success are the ones that I pushed back for years. I didn’t want to take portraits because I didn’t want people to think I was doing Malick Sidibé in color. One thing I’ve decided now is: if I have an idea, I’ll shoot it. I won’t waste any more time trying to figure out how people are going to think.

With “The Studio of Vanities,” even though the style involves many visual references to other generations, I’m trying to capture something that is contemporary. This was just a visual language that I had, and that I use, because it’s my heritage. I’m continuing a conversation.

‘Studio Portrait(s)’ is on show at Galerie du Jour through March 19.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Omar Victor Diop, courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A