It’s rare an oil painting cuts through the abundance of photos we consume every day. In the glut of memes and videos and all of the loud content vying for our attention, as a visual medium, painting can go largely unappreciated online. Though, as Oscar yi Hou notes, the past two years of lockdown has compelled the art world to look more online, “which I think was a factor in putting my practice onto people’s radar,” he says.

Oscar is an emerging 23-year-old artist from Liverpool, now based in Brooklyn, and his portrait series A sky-licker relation, created over the last two years and presented recently at James Fuentes, is rich in colour and generous in its portrayal of its subjects; rendering each as a character worthy of far more than just a fleeting glance. “The choice to depict someone else is always political,” he says. “For me, it should be an act of respect and a way to honour the fact that you always live your life with other people, among other people. It’s a way to give testament to the shared, social lifeworld we all live in.”

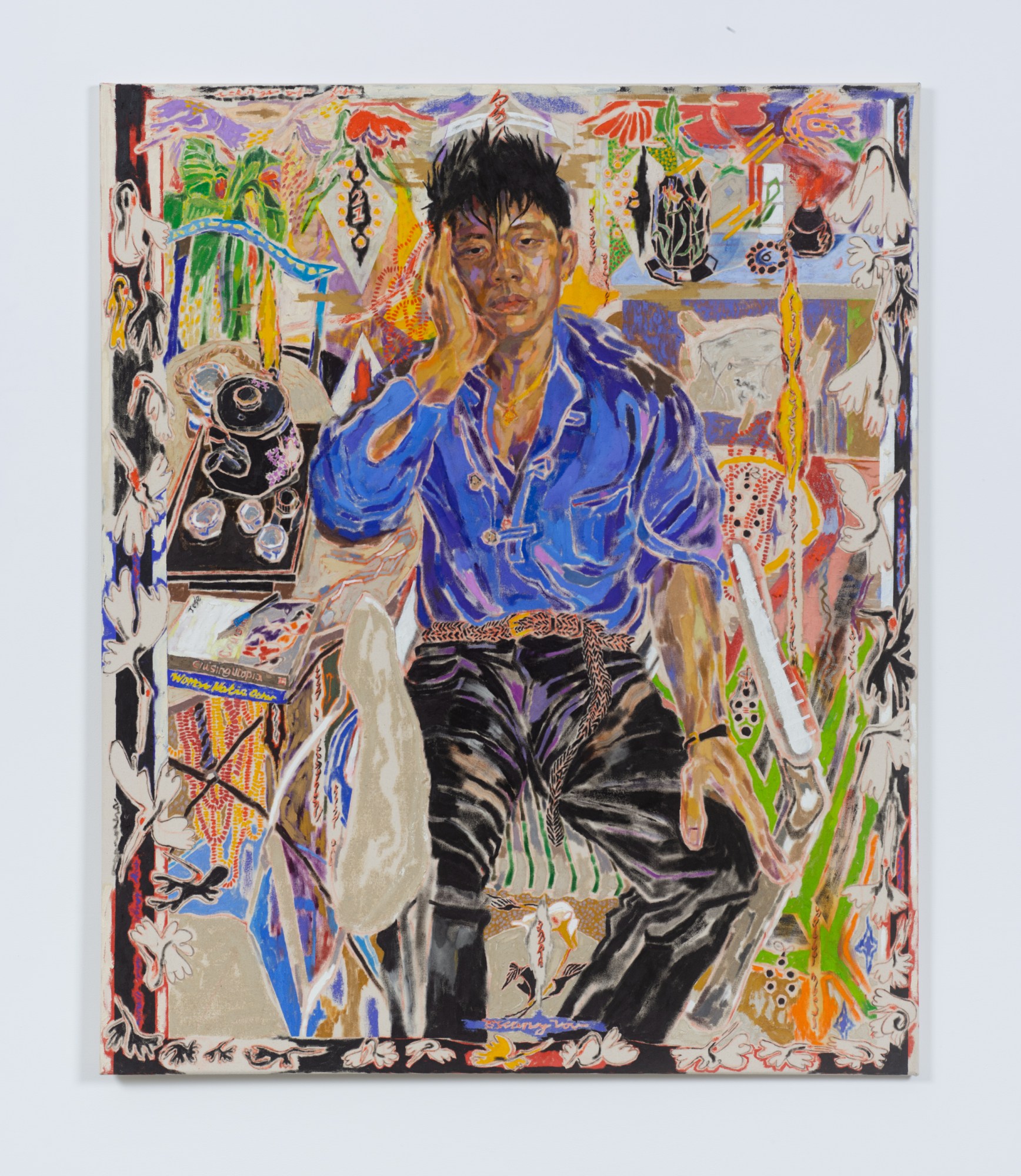

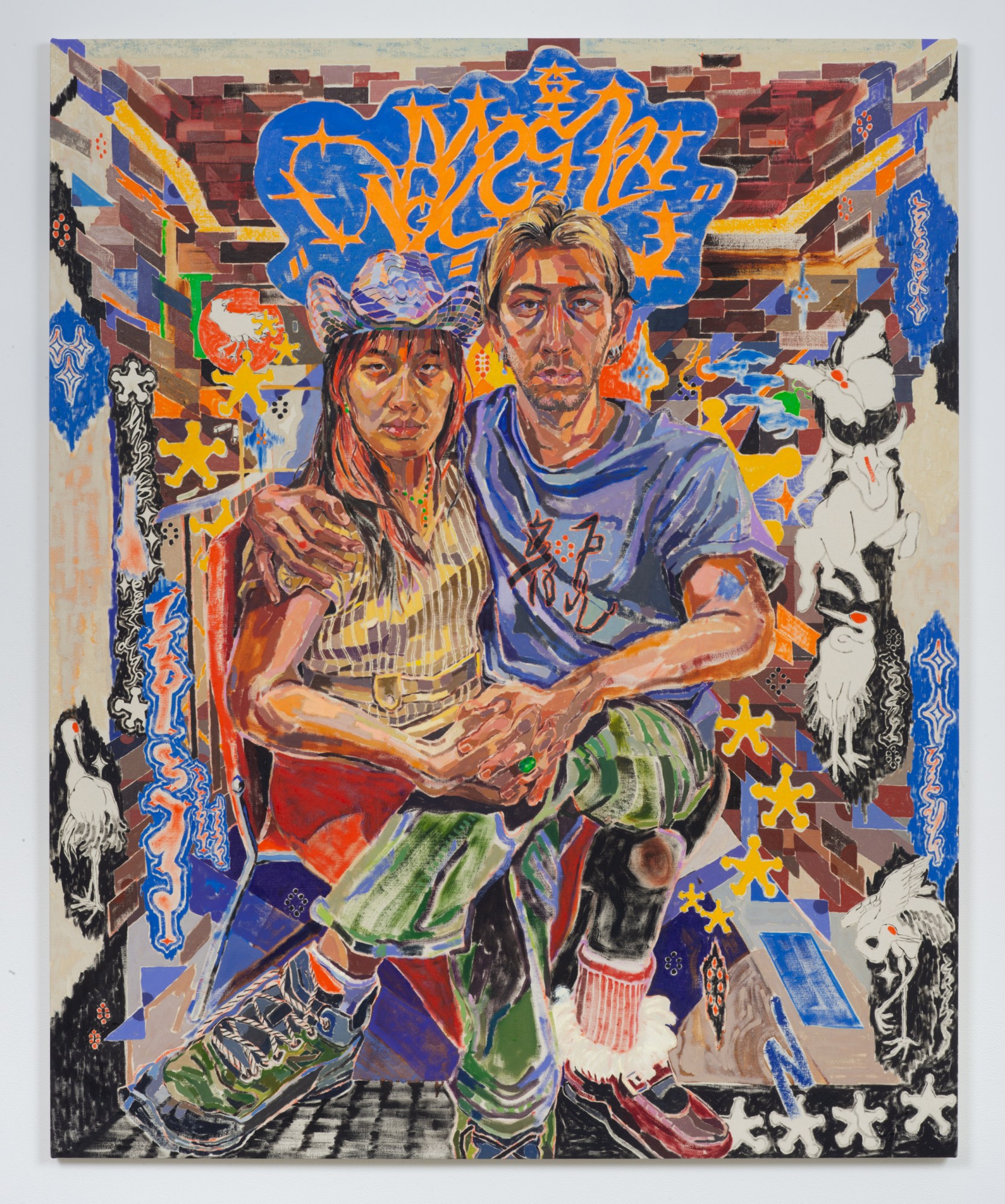

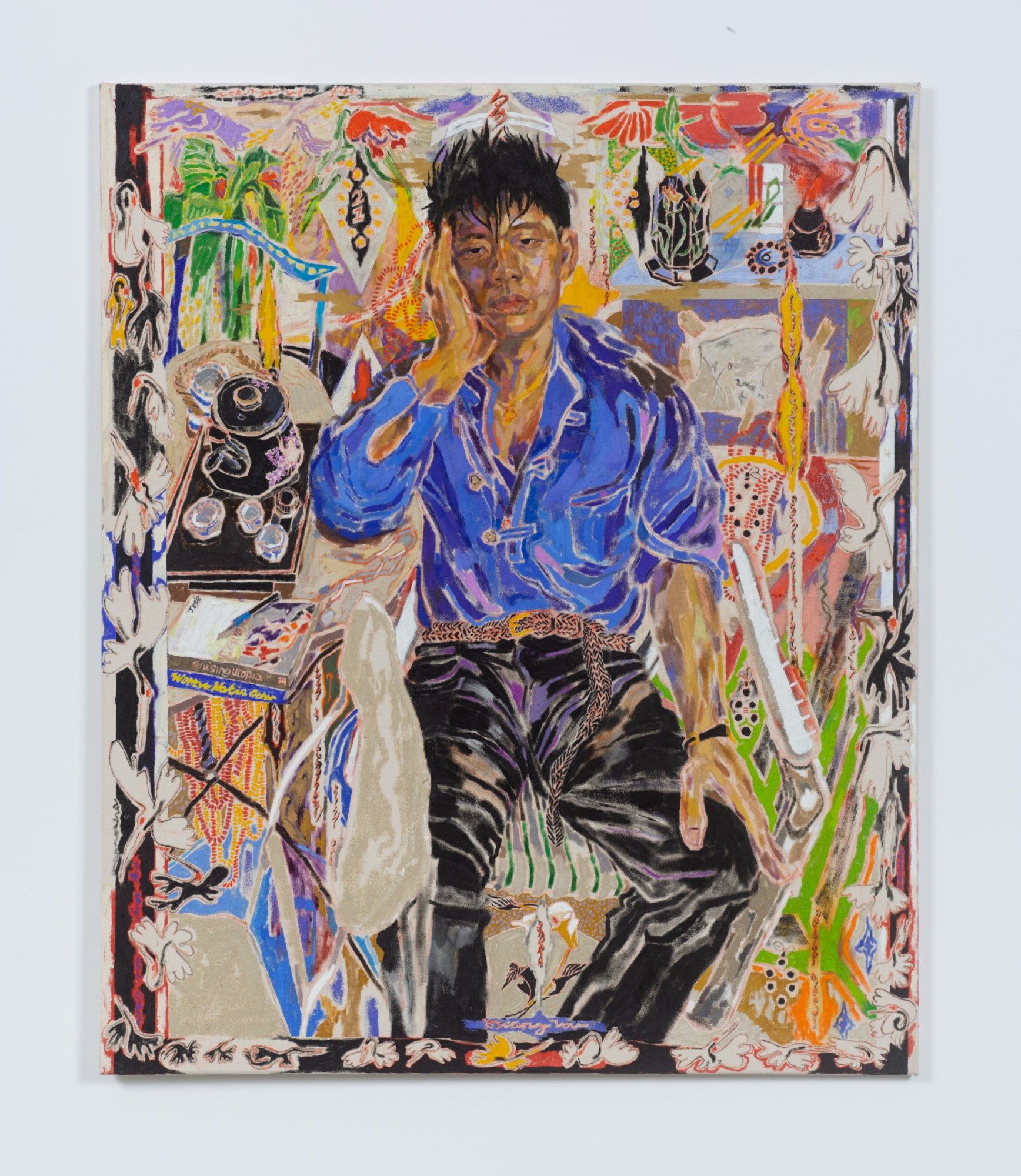

The artist speaks passionately about the bond he forms with his sitters, choosing only to paint portraits of those he has a close relationship with. Framing each against a backdrop rich in symbolism and a kaleidoscopic palette made with layers upon layers of oil paint, each of Oscar’s paintings seems to answer, or at least raise questions about who its subjects truly are, even in the canvases’ most subtle details.

One of the series’ most striking portraits, “Forlorn fire-escape flowers, aka: New York strings of life, 2020“, exemplifies this approach, as well as the mixture of references that go into each painting. Taking its name from the seminal 1987 Detroit techno track “Strings of Life” by Derrick May, Oscar painted it when he was “feeling particularly confined by lockdown and wanting to go dance in a club,” he says. In it, his subject, a young man dressed casually against a swirling backdrop suggestive of a hot summer’s afternoon in the city, holds onto a bunch of flowers and branches, looking – as the name suggests – forlorn, but also regal, in a way oil paint on canvas has done so for centuries.

Amidst the foliage in the subject’s hands sits a bird – or a sky-licker, perhaps, a translated word taken from an Aimé Césaire poem and given to the whole series, a reference to Oscar’s own Chinese given name, 一鸣, meaning a bird’s cry. The bird throughout this work is often a stand-in for himself within the picture, nodding to his own place within this artwork and his subject’s universe.

As he’s awarded the UOVO Prize — a solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, a public installation on the facade of UOVO’s Bushwick Facility, and a $25,000 grant — we chatted to Oscar about these different references, symbols and ideas in his paintings, as well as the story of how he came to create them.

Where does the story of your art begin?

I actually started out drawing a lot of digital fanart with a graphics tablet, specifically of Pokémon. Some of that stuff is probably still floating around the ether. I grew up on the internet and spent my tweens plugged into these relatively wholesome online communities, orbiting Tumblr, chatrooms, and other internet forums, where I’d lie about my age and say I was a teenager (in retrospect, I assume that everyone else was lying too). My parents were also always working in the restaurant, so I was often left to my own devices. I was making art all the time and spending hours on the internet. I’d say that a lot of my basic art education first came from the internet, learning colour theory from sites like DeviantArt.

Once I entered my adolescence, I took Art GCSE and transitioned to physically painting with acrylics. I visited the Tate Liverpool often, and I was introduced to British artists like Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud. I’d learn from them by making studies of their works. On the internet, my interests changed too, and I began to consume countless images of art, photography, films, architecture, etc. I was scrolling through hundreds of beautiful images a day, which I feel really honed an eye for composition and aesthetics. I developed a taste in what I liked and what I didn’t like aesthetically.

I’ve always been interested in people and portraiture. I made many portraits of my friends — for some reason, I always felt like youth was something sacred and slipping away from me, so I always felt inclined to document it. I did a series of paintings of various friends being drunk at house parties. I made these huge photo albums of images I had taken throughout my adolescence, thinking that I would leaf through them in nostalgia one day, though, of course, I haven’t touched them in years. Then I came of age, went to university, and stopped giving a shit about youth!

I actually wanted to go to art school, but in the U.S., they’re incredibly unaffordable for international students. At Columbia, my tuition was basically covered by my financial aid package, so that’s where I ended up going. Ultimately, I’m grateful I got more of a liberal arts education than a specialised art school education — it shaped my art practice for the better.

What did you grow up on beyond art – musically, film, TV-wise?

My parents never really had particular music or film tastes of their own, so it was something I had to find for myself. I was definitely an indie kid growing up, so I grew up on a classic cocktail of indie music and film during the late 00s and 10s. I’d pirate so much film and music. I’d torrent these long-ass playlists from The Pirate Bay to try and discover new bands and sounds.

I was always interested in finding something more than just what was provided to me, and I was consuming so much content. I wasn’t really doing much else besides school, art, and playing video games. This was before Spotify, before content became so formalised, so you really had to venture out into cyberspace and discover things for yourself.

Tell us about “A sky licker relation” – the name and the work that it is composed of?

“A sky-licker relation” was my solo show at James Fuentes last year. “Sky-licker” comes from an English translation of an excerpt of Aimé Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal. I came across it years back when I was reading Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon. I was struck by the poetics of the phrase — you come across the figure of the bird, and metaphors of flight manifest across many different spheres and artforms. I was recently reading Younghill Kang’s fictionalised memoir, East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee — he was an important early Asian American writer — and he uses a beautiful metaphor of an “undying bird” that flies “on and on.” And in one of my favourite collections of poetry, “A Coney Island of the Mind” by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who recently passed last year, there are so many birds — my favourite are his “moonmad swans.”

I’ve always felt a particular affinity for the idea of flight. It’s something I explore within my poetry, too. And throughout my body of work, I use the figure of the bird as a signifier for myself, in reference to my given Chinese name, which comes from an idiom involving a bird’s cry. So, in brief, the title “a sky-licker relation” speaks to how these portraits are all expressions of the relationships that I share with people.

Tell us about the sitters for these pieces, who you chose to paint, and how they interact with the wider iconography and symbolism they’re ensconced within inside the frame?

I wanted to try and be as responsible as possible in my representations of other people. I was driven by questions such as: who gets to represent whom? Who gets to speak on behalf of whom? So, rather than painting a lone subject, which would be to “speak for,” I wanted to instead the depict the relationship that I share with the sitter, which is instead to “speak near” or “speak with.” I was inspired by the thought of filmmakers like Trinh T. Minh-ha. I was also inspired by the poet Frank O’Hara’s manifesto on “Personism,” which is, to summarise, about painting as a form of address to the other.

So in this body of work, I only painted people I had a particular relationship with. You can see this symbolically in my works. There are a variety of symbolic languages I draw from, such as astrology, the zodiac, or any tattoos the subject might have. For example, in “A crane and two sea-goats walk into a bar, aka: Summertime Cosmogony on Old Broadway (2021),” the two subjects depicted are both capricorns. They’re dating, so I depicted them as a two-headed sea-goat. Above, I depicted a crane. The juxtaposition of the goat and crane represents our shared friendship. The motif of three-ness is also seen throughout the piece.

In other pieces, there are fragments of poems that I wrote about the relation I have with the subject.

The portraits feel quite frenetic and loud despite the stillness of the subjects; what’s the process of creating portraits like these, the speed and the precision or the lack of?

I always begin with the eyes — I’m a sucker for eyes. Before that, though, I do a sketch or two and draft up a rough composition for what I want the piece to look like. And I’ll do a drawing with some gouache directly onto the canvas to help guide the work.

I get very single-minded once I start rendering the face. Even though it requires the most work, precision, and thought, I’ll often lose myself and can often complete it within the week. It’s the most fun and is always a joy. I’m always very intentional with which hues to use, and the shape I want each brushstroke to create.

In my day-to-day life, I’m not known to be a very frenetic person, but sometimes within a painting, you have move quick in order to give some weight to the more slow moments.

Overall you presented three solo exhibitions last year, did 2021 feel like something changed in the way you made art or the way it was received? Has the last two years and the disruption shaped you as an artist in any way?

Beginning my career during a pandemic has been a little crazed. It forced me to hustle a lot more. Last year was a ton of work, as I produced those three shows and also completed my final year of undergrad. It’s hard to really delineate the way that these past few years have shaped me as an artist, because the disruption the pandemic wreaked also significantly shaped — and continues to shape — my post-graduation life. The last two years of my degree were over Zoom; I had one of those silly little Zoom graduations. It’s a little sad to think that I don’t really know what young adulthood was like before, because adulthood during a pandemic is all I’ve ever known. I’m fortunate because art-making is a generally solitary affair, and I’m self-employed. My peers and other recent grads have had it far worse. I’m very grateful to be able to do what I do.