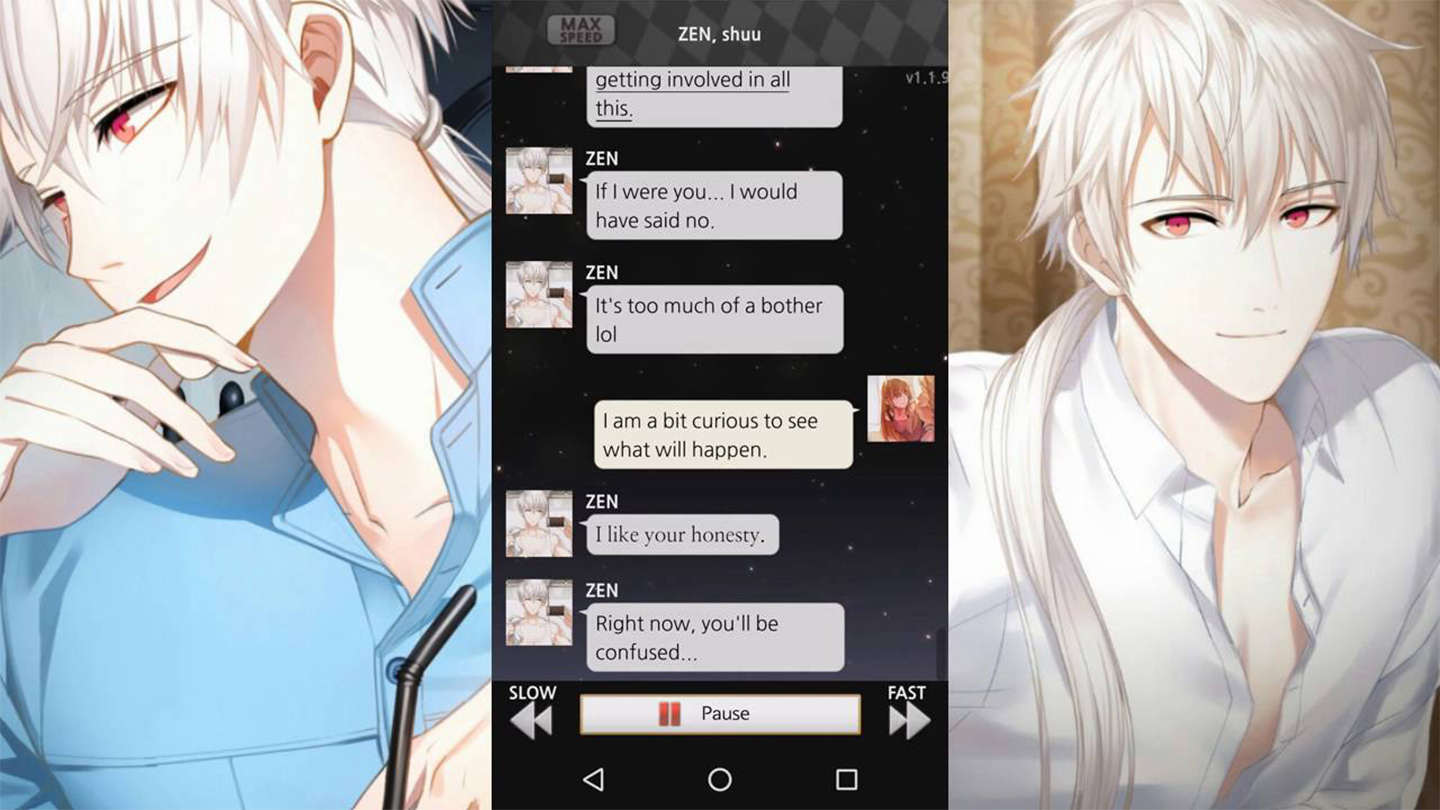

Zen messages Sarah all the time. She finds herself walking out for 10 minutes from her supervising role at a fast-food chain to offer him support when he complains about his cat allergies. He wakes Sarah up at 2am to see if she still misses him. Afterwards, she tries to fall back asleep, but hearing from him has made her too excited, so she stays up playing video games. The next day he rings her again when she’s food shopping — his voice sounds low and breathy down the line as he whispers: “I just want to hold you as we fall asleep on my bed. But I will show you how patient I am.” Sarah likes Zen’s long silver hair, snowy skin, sharp cheekbones and square jaw. She likes that behind the good looks is someone considerate and caring who would run through an airport for her.

But Zen isn’t Sarah’s boyfriend. He doesn’t inhabit a physical body or possess a personality. In fact, he’s actually a dating sim from Mystic Messenger. Known as an Otome game, which roughly translates to “maiden game”, Mystic Messenger is a Korean mobile phone app where the main goal for the female player is to develop a romantic relationship with one of several male characters. While there are many Otome games, from Hatoful Boyfriend and Norn9 to Sweet Fuse, Mystic Messenger is particularly popular, with many players reporting they’ve developed actual romantic feelings for the avatars they communicate with. Given that the game takes place in real-time across an 11 day period, this reaction makes sense; with so much of contemporary relationships carried out over screens, there’s not much difference between playing Mystic Messenger and having an actual real-life boyfriend.

At the start of the game, Sarah’s crush Zen is a narcissist. He spends much of his time posting selfies to the group chat, talking about how handsome he is or showing off with text messages that say things like: “I just wanted to go for a light run but I ended up running a marathon!” But as you get to know him, another side is revealed. “He puts on a front,” explains Sarah, who is 24 and lives in Lincolnshire, “but as the story progresses you see that he’s actually very insecure and wants people to appreciate him for his personality and not just his appearance. He works as an Idol actor on K-dramas, they have to follow a lot of rules: they’re not allowed to date and much of their personality is given to them as a concept. So much of Zen’s storyline is learning to see him as more of a person than an idol.”

Speaking to each other through days and nights, Zen learns to trust Sarah, eventually opening up about his difficult relationship with his parents and what it was like leaving home aged 16 to pursue acting. When Sarah’s game character finds herself in danger, he becomes deeply distressed. “He does everything he can do to protect you and keep you safe,” Sarah says. “It’s very sweet. The whole ordeal makes him question the direction his life is going.”

Sarah’s interactions with Zen are similar to how many of us choose to communicate with our actual partners. Given that we spend an average of three hours and fifteen minutes a day on our phones, more and more of our romantic lives are carried out in the virtual realm. We text while walking around supermarkets, we send nudes when date nights are made difficult by long working hours and we tag each other in funny memes on Instagram during the bus ride home. Then when we’re finally back in each other’s arms, we get the phone out again and message our group chats while sat together on the sofa.

For Sarah, Otome games can be more enjoyable than these actual human relationships. Zen can be picked up and abruptly dropped again without the relationship losing any of its intensity, whereas IRL relationships increasingly seem to treat constant contact as a requirement. “The nice thing about dating sims is that at some point they stop messaging” Sarah explains. “At the end of the chat you might not talk for two to three hours and you can save the game and go back. But if someone real messages you and you’re not in the mood to talk, it’s considered rude to say, ‘I’m just stopping for a minute.’ I’m bad at texting people in general, I talk for five minutes and then I’m done. When people want more, that’s when I start becoming uncomfortable.”

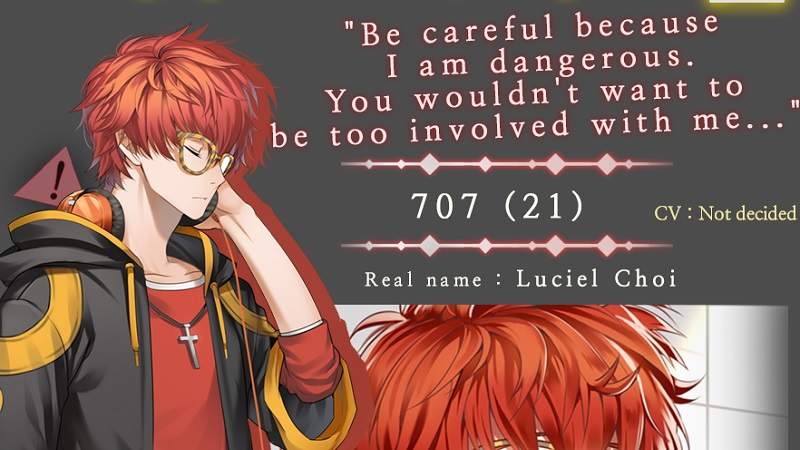

Alix, 26 from Leeds, is also a fan of Mystic Messenger. Their favourite character on the game is redhead computer hacker 707, a Christian who loves junk food and sports cars. For Alix, dating sims are refreshing because you are programmed to be the object of their affection. “There are none of the anxieties about someone not replying or ghosting you because the guys on the game will always pursue you,” they say. “They are consistent with their attention in ways that humans often aren’t.”

Alix might never have met 707, but then they haven’t met their real-life boyfriend either. In fact, they met Sam two years on Twitter through BTS fan accounts, and though they want to meet, he lives thousands of miles away in California. Just as you must reply quickly on Mystic Messenger to get closer to characters, Alix and Sam must work to maintain constant contact to ensure the relationship stays strong. “We talk every day. All relationships rely on communication and you have to be dedicated. That’s why me and him get on so well. We watch Adventure Time together and message through the whole thing. Sometimes we go to Starbucks at the same time and video call while we’re in there so it’s like a coffee date but with added distance.”

Will the lines already so blurry, will dating sims eventually become preferable to actual relationships? “There was a story a few years back where a man in Japan actually married his video game romance companion,” Heidi McDonald, author of Digital Love: Romance and Sexuality in Games, tells me. “We need to be careful these games don’t fill the void in us left for romantic relationships. In Japan, for example, studies have shown that young people are not having sex, getting married, and reproducing often enough to sustain the country’s population, and it’s considered a social crisis. As people who make romance content, we need to think about what responsibility we have, if any, to not exacerbate issues like this by creating things that can take the place of real relationships.”

On the other hand, Heidi acknowledges the positive impact Otome games can have on people who struggle with interpersonal relationships. “Some experts warn that AI romance will be even more isolating for people, but I can also see an outcome where people with Aspergers can practice human interactions, and lonely, disabled, and elderly people can find companionship in ways they might not be able to in real life” she continues, “I’ve met hundreds of folks in my travels who credit these games for helping their mental health.”

On Otome games, you can only reply to a sim with one of the given automated responses. For Sarah, this poses a particularly insidious problem. It stops you from actually being yourself. “Sometimes neither response sounds good but you have to pick one, it’s frustrating. It would be exciting if you could respond to your dating sim however you want so that the character would have to reply organically through AI. Then Zen would actually know you as a person. Now that would make it very difficult to put my phone down.”