At the entrance to this year’s edition of Frieze London a street vendor stands selling souvenirs and bags. Another is walking around the fair, upon his back is a an advertising hoarding, “where we’re going we don’t need roads” it reads. A woman dressed in a Pikachu onesie is handing out flyers. These living sculptures are the work of Lloyd Corporation and they are magnificent. Their work at Carlos/Ishikawa’s booth is set up to look like an internet cafe, plastered with signs and ephemera from across the world; one of those giant Sports Direct mugs rubs up against Bollywood DVDs next a keyboard, on one of the computer monitors, a subtitled grainy newsreel of Putin meeting middle eastern political leaders plays on loop. Lloyd Corporation’s work is a grotesque, amplified take on a universal architecture of marginalised spaces of the kind frequented by the marginalised; the immigrants, the poor, the very same people who have to be out selling dodgy souvenirs, or who have to find work as walking advertisements in order to make ends meet. It’s a giddily successful, if eerie and uncanny, intervention into the architecture of Frieze, a comment on the global capitalism that Frieze is such an emblematic part of. It’s not particularly beautiful work, in fact it’s brutal, aggressive incongruousness makes it stands out from the sea of booths.

It’s sometimes hard to work out what the point of Frieze is as someone who isn’t an art collector. It’s not really the easiest place to see or appreciate art, there’s so much to see, and 90% of it is ruthlessly stripped of context. So when something slips in amongst the stalls, like the work of Lloyd Corporation, that works to turn the heady commercialism and rampant capitalism the art fair thrives on into its very concept, then it’s all the better. A reminder of the point of Frieze for someone who isn’t an art collector. There’s plenty being displayed by the young galleries this year that makes the trip to the fair worthwhile. In fact it’s where the real gold lies.

Now in its 14th year as a fair — and also celebrating the 25th birthday of Frieze, the magazine — it has throughout its history ruthlessly positioned itself not just as simply a trade fair but as a kind of cultural barometer for the art world in general. This leads to those spectacular booths that seemed designed to steal attention and grab column inches instead of sell art. Though of course standing out is quite a good tactic for selling art, especially if you have a load of beautiful, expensive paintings you can whip out of storage at a moment’s notice. Though noticeably only Hauser & Wirth have gone this route this year; they’ve crafted an atelier of objects, arranged to resemble something like a millionaire’s Muji stocked with work by everyone from Mark Wallinger to Martin Creed, Louise Bourgeois to Isa Genzken. It’s a staggering constellation of work of course, and plays up (or plays on) the shoppy nature of the fair.

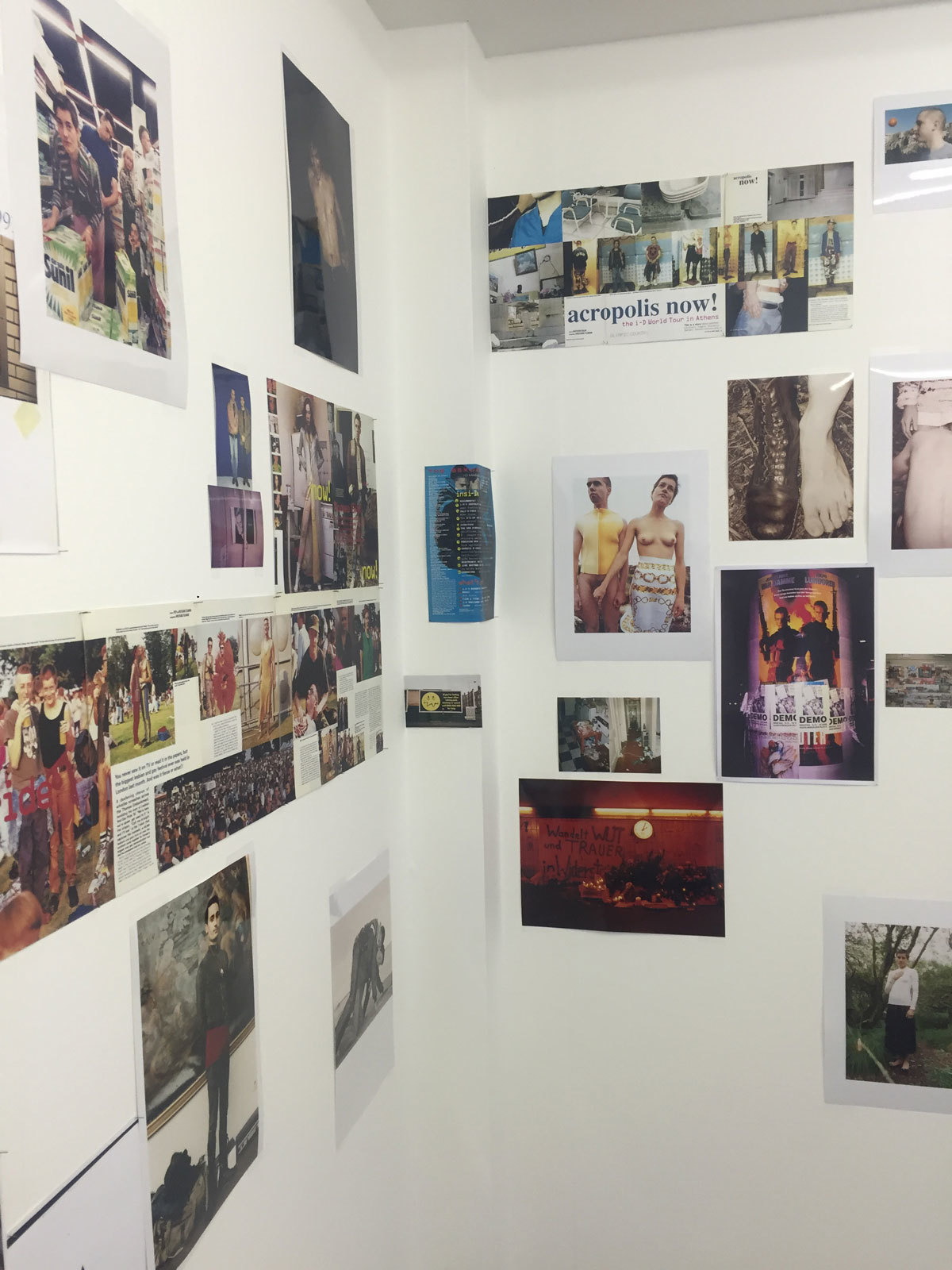

The Nineties is a new section, developed to celebrate Frieze’s 25th year, and seems to reach towards a suggestion of the fair’s place as a place to see and appreciate, not just buy, art. It reconstructs a series of iconic works and exhibitions from the early part of the decade in the fair. It’s of obvious interest, but it’s hard to work out what the point of it all really is. Is it for sale? Is it for the casual viewer? The curious? A stake for relevancy? There’s great work to be seen though, sometimes that’s enough. The undoubtable highlight being a reconstruction of Wolfgang Tillmans’ first ever exhibition, hosted in Daniel Bucholz’s Cologne gallery in 1993. The display here features many of the photographer’s iconic early images, including pages ripped from old copies i-D featuring work he did for us on rave, Berlin, and Shabba Ranks, as well as some of his early fashion work, and his instantly recognisable snapshots of friends that are now etched into our collective consciousness. It was an incredibly important exhibition for Wolfgang, the way it mixed “art” images with pages ripped straight from magazines, images hung in an un-hierarchical manner across the space. It was bold and new and fresh, and time hasn’t dulled the sense of joy in seeing it.

Across from Wolfgang’s section, is the work of Pierre Joseph, whose work involves small gestures and enigmatic scenarios being undertaken by a range of costumes performers. Characters to Be Reactivated is a series of tableaux vivants constructed between 1991 and 96, and features a sweeping Cinderella, a leper hidden under a blanket, and an American policeman handing out printed manifestos calling for fictional characters to revolt against their creators; “WE NEED MEANING” it states at the manifestoes end. The rest of section is fleshed out by the restaging of Massimo De Carlo’s Aperto 93 exhibition, which launched the careers of the likes of Carsten Holler, Mauricio Cattelan, and Rirkrit Tiravanija. And Richard Billingham’s 1996 Ray’s A Laugh, a series of emotive, shocking, honest, and beautiful images of his family, that would, alongside Wolfgang, help define photography in the 90s.

Apart from Hauser & Wirth, at the biggest galleries at Frieze this year it felt like there was a kind of paring back of the ridiculous OTT in favour of restraint, or whatever passes for restraint amongst the global art world. White Cube’s booth is stuffed with old Damien Hirsts and a beautiful new Tracey Emin painting. Lisson, apart from a massive Anish Kapoor mirror sculpture, have even elected to show John Akomfrah’s work from last summer’s Venice Biennale, any chance to rewatch it is a pleasure. Spruth Magers have got a series of rather chaste nude drawings and some large pastel-shaded aluminium paintings by Gary Hume alongside a selection of Cindy Sherman works. Zwirner have a booth full of Kerry James Marshall’s paintings, which are incredible. There’s a James Turrell light piece in a little tucked away corner behind Kayne Griffin Corcoran’s booth, that promises much, but its possibility of something spiritual is stripped away by the context of the fair. The Gagosian have given over their whole booth to the quiet sculptural ceramics of potter Edmund de Waal, another work, ostensibly beautiful, whose contemplative properties, like Turrell’s, are nulled by the bustle of Frieze. So maybe bigger and bolder and brighter is actually, really better. What’s the point of the fair as a non-collector? Well, it’s to be wowed.

There were of course booths that did totally work. Simon Lee presented the paintings of Hans-Peter Feldman, whose appropriation and interventions in classical portrait paintings are a total joy. Hans-Peter spent time sourcing 19th century portraits at auction and subtly modifying them; make the sitters cross eyed, cutting out faces, painting red noses onto dogs, tanlines onto nudes arranged on a maze of stands for you to weave through. Pilar Corrias unite Philippe Parreno’s bright orange floating balloons with a video installation of work by Shazia Sikander, in a booth that feels like an enchanted grotto.

If much of the main section felt restrained, it was left to the fringes and Frieze Focus to provide the excitement. Specifically London’s young galleries, who presented much of the fair’s best and most engaging work.

Arcadia Missa, who last year showed work by Amalia Ulman as part of Frieze Live, this year return with a group booth featuring the work of Jesse Darling, Dean Blunt and Hannah Quilan and Rosie Hastings. Jesse’s sculpture is the stand out though, and maybe the stand out work of the fair itself, a towering army of typical school chairs perching and huddling together on elongated legs. They are menacing and terrifying and awe inspiring. The Sunday Painter, like Arcadia Missa based in Peckham, and who last year won plaudits from everyone with Samara Scott’s sunken floor pool, this year present the heaviest work ever displayed at Frieze. It’s by Rob Chavasse, and it’s an intrusive, sculptural stack of plasterboard, printed with pixellated dots taken from a still from one of Chavasse’s video works. The dots mesh with the markings on the board to form an image when seen from a distance. The plasterboard is merely on diversion though, for sale yes, but once bought it returns back to the system to end up in someone’s house; as a collector you’re essentially paying for it’s display at the fair. A bold conceptual move for the young gallery, but one that works well, gains attention, and also looks beautiful.

Seventeen Gallery, showing at Frieze for the first time, present a VR work by Jon Rafman, that you can queue up to experience, or, more excitingly, you can just watch the people lost in an Oculus Rift art world. Southard Reid, also showing at Frieze for the first time, have given over their whole booth to Celia Hempton’s beautiful paintings of erect cocks. Celia has also smeared the walls of the booth in shades of cream and beige, that lend the members a delicate, humorous softness. Lambeth’s Chewday’s, another Frieze debutant, have brought together the work of contemporary artist Gabriele Beveridge, and paired her with a selection of neolithic idols. There’s a rather uneasy if inspired juxtaposition between the photographs of beautified faces that make up Gabriele’s work, partly obscured by abstract glass shapes, and the forms and shapes of the ancient sculptures abstracted by erosion and time, and arranged over a glittering lightbox. Notable shout outs to High Art and Societe, from Paris and Berlin respectively, for two excellent booths as well. But the Focus section of the fair this year really showed the astounding depth of talent and potential that litters London’s art scene right now.

Outside the booths it was left to two of the projects to offer the most thrilling moments of the fair, in the form of Frieze Artist Award winner Yuri Pattison, and Julie Verhoeven. Both actively respond to the weirdness of the fair, the fact that it’s a transient, junk space for culture; a contemporary art version of an airport duty free lounge.

Julie Verhoeven has taken over the fair’s toilets and turned them into a candy coloured dreamland; she’s removed the gender signs, carpeted the boys toilets in pink, the girls in blue. This results in quite a few uncomfortable moments, it’s wonderfully confusing, delightfully unsettling. You’re greeted by a sculptural assemblage, and Julie herself working as a toilet attendant. There’s a cardboard cut out of Paris Hilton in a Roman centurion helmet. The bogs themselves are clad in cutesy pink foam covers, they are piping in power ballads. There’s an awkward, funny, frisson of danger about entering; between bodily function and art. Turning humdrum fair space into something magical.

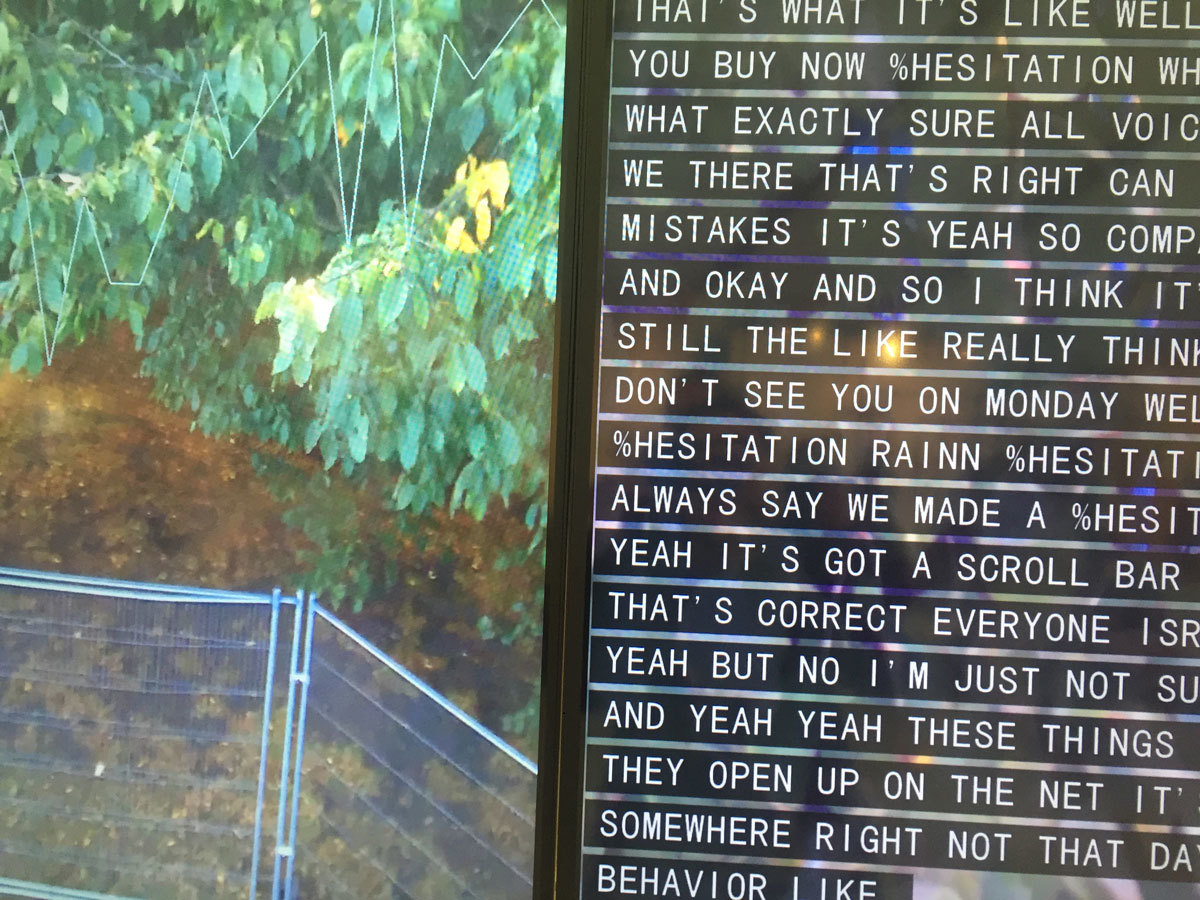

Then Yuri Pattison, who’s created a massive installation of TV screens, called Crisis Trollet, that responds to the conditions fair by beaming in a live feed of the space above the sculpture, and draws on the “internet of things” by collecting data from specific sites within Frieze and feeding it back into the monitors in a live update of fair goers’ behaviour and chatter. It’s hypnotic to watch it in process, there’s a weird disconnect between reality and science-fiction, seeing what’s going on around you through the filtered data bubble, and out-of-body experience. In the way it grapples with the world we live in by imagining the world we are possibly about to live in (big data is coming for us all), it feels like the most relevant, nuanced, and interesting work in the fair.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography courtesy of Linda Nylind/Frieze.