The Venice Biennale is an international art exhibition that takes place every other year, and began in 1895. This week it’s 56th edition opened, titled All the Worlds Futures. Curated by Okwui Enwezor. All the Worlds Futures is an apt and coherent framework for such a gigantic event in the art calendar, especially one that’s built around each country occupying a pavilion – especially as the Biennale often ends up as a form of cultural state marketing. In a fairly strong move, All the Worlds Futures attempts to eek something more than this out of the Biennale. Enwezor says that the theme is directly examining “the ruptures that surround and abound around every corner of the global landscape today. How can the current disquiet of our time be properly grasped, made comprehensible, examined, and articulated?”

Walking along the side of the Arsenale, Venice’s medieval, industrial shipyard where part of the Biennale resides, one sees the work that will probably get the most views during over the course of the Biennale – which runs until November 2015. Out of Bounds, by Ibrahim Mahama, a young Ghanaian artist, consists of “coal sacks, metal tags and jute ropes on coal sacks” and covers the two walls that flank the most walked path around the side of the Arsenale – the well-trodden path takes visitors to toilets, restaurants, more art, etc. The piece is extremely post-apocalyptic, resembling Waterworld. Its doom laden, the threat of something impending, the sacks reach the heights of the walls and steeply look down on you. They are shorn, they smell of damp – you don’t know if it’s from the buildings they wrap, the bags themselves, or the general smell of this city-in-the-sea.

Mahama’s work questions the conditions of supply and demand within African economies. These bags were originally used for cocoa, and then reused for coal. They are marked with their country of origin or their owner’s names, they’ve been patched and re-patched, just as the artist himself does as he works them into his large site-specific installations. The questioning of value is continued by the location of this work in the Arsenale (outside and likely to be damaged as it’s worn by the weather over the coming months), as it is when the artist has previously exhibited the works – back in the markets they have come from as well as galleries. The values of specific things are always derived from their contexts.

This work epitomises the strength of this year’s Biennale and a lot (not all) of the work that is part of it – something not so happy, a knowing reference to the world outside of its art. The fact that you can feel a real critical edge this year does cut into the competing nationalisms that the Biennale fosters; a petty “our art is better is than your art” style competition, mirrored by the global billionaires who roll up in ever bigger, ever more vulgar and expensive super yachts.

The old empires have the oldest and grandest pavilions in the Giardini, and lots of countries don’t have pavilions in the Giardini at all – culturally exiled to the Arsenale, and dotted around the city. These hierarchies are predicated on the ways that nations are strung together within global capitalism, and this nod to material in art – as in relationship with – the goods circulating African markets, begins a conversation on these imbalances of power.

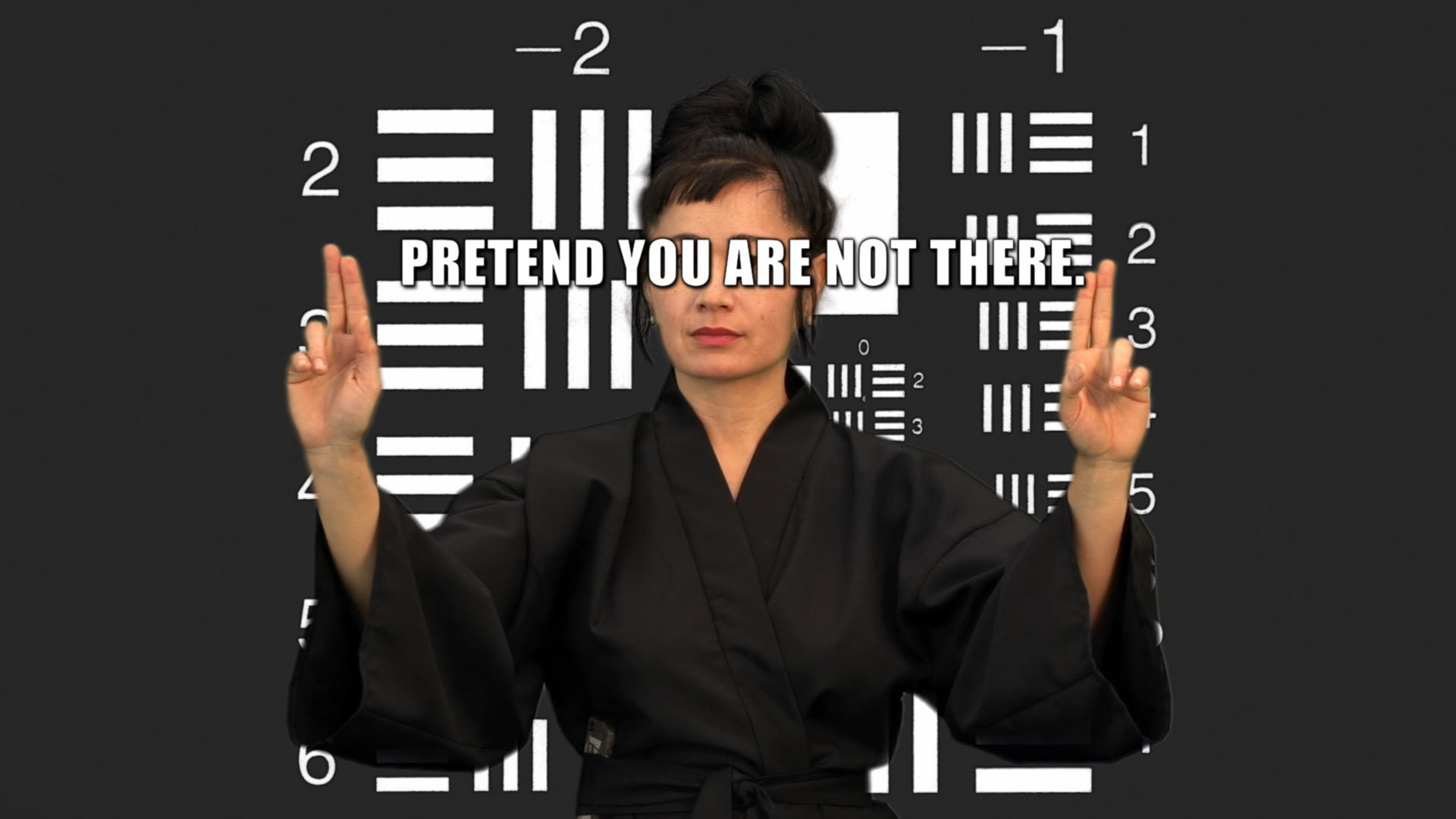

This theme is continued, yet attacked in an entirely different way, by Hito Steyerl’s outstanding video piece in the German Pavillion in the Giardini (a group show, entitled Fabrik, featuring the work of Olaf Nicolai, Tobias Zielony, Jasmina Metwaly/Philip Rizk and Hito Steyerl), in which one character ‘from’ the Deutsche Bank states they “did not flatten Greece and Portugal”. Steyerl’s work, entitled Factory of the Sun is a 23-minute video installation that catapults us into a near future (part video game, part reality) we follow photons, or ‘orphans of the enemy’ – as protagonist-revolutionaries that epitomise the classic symbol of sunlight as a part of progress – threatened by drones and the Deutsche bank, dancing as a last form of resistance. The video is a mix of green-screen acting and outstanding CGI close to Hollywood films or Role Playing Games – spheres of light, explosions, gunshots, all flare up on the screen within the dark room marked out as its cube by thin blue lines in grid form all along the wall and ceiling. We watch the film in sunloungers and are too embedded in the desire and capture of light.

Aside from Mahama, other highlights of the Arsenale include Helen Marten, Gedi Sibony, Harun Farocki, Sonia Boyce and Maja Bajevic, and a video by Coco Fusco. Fusco’s video focuses on Herbeto Padilla, a Cuban poet, and the ‘Padilla affair’ that he was the centre of when he was imprisoned by the Castro regime in 1971 for speaking out against it – often through his poetry. His incarceration prompted a letter from the international left-wing intelligentsia (such as Jean Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag and others). He was eventually released, but essentially silenced. Fusco asks, what about his local literary community, what about Padilla himself – to what extent do we not look at what is in front of us?

Notable spots outside the Giardini and Arsenale include the Research Pavilion by the University of the Arts, Helsinki; Simon Denny’s Secret Power, an NSA-inspired installation for New Zealand at the Marciana Library; The Internet Saga, a two-part exhibition of Jonas Mekas’ works; and the Antarctic Pavilion. The Antarctic Pavilion is a provocation to the Biennale’s formation via nation states – no-one technically owns the Antarctic, yet the most dominant countries still have processes of occupation, be that exploration, business interests, or science. The Antarctic pavilion was initiated by the artist Alexander Ponomarev and speaks not only of the questions surrounding ‘nation’, but also of the future of one area being at the hands of as well as profoundly affecting, all the world’s futures, or, the future of the rest of the planet.