In 2021, I decided to re-frame the purpose of my life by opting for hedonism. My year was spent ordering a second glass of wine and kissing people in public. For the first time in my life, I stopped worrying about “bettering” myself and instead centred pleasure. This pursuit was the most fulfilling and natural I’d ever encountered.

After all, pleasure is a biological necessity. In his book The Pleasure Center, psychologist Dr. Morten Kringelbach defines it as “a way of fulfilling the evolutionary imperatives of survival and procreation.” Pleasure is also dependent on the delay of desire. In other words, pleasure is heightened when you want something, and need to work or wait to achieve it. Distinct from joy or happiness, it’s a larger, longer experience stemming from actualisation, not output.

After my year of hedonism, I sought to live a balanced life where some form of pleasure remained a goal. Framing the completion of a simple task — be it sending an email I’d been putting off or cooking a meal — as an opportunity for pleasure helped make my life more enjoyable. But as I slowed down and focused on what was pleasurable, the world around me seemed to be shirking it. Something new was trending, popping my contentment: discipline.

Motivational speeches by toxic “alpha-male” “influencers” like Andrew Tate, shouting about the gospel of discipline were increasingly trending on Instagram and TikTok. Spliced over videos of bench presses, 10-hour study sessions and vegetable-forward meal preps, before-and-after weight loss videos started trending once more, after a dip in popularity during the height of the body positivity movement. Discipline, in the toxic masculine sense, now had a visual accompaniment. It was no longer about the commitment to work towards a personal goal. Millions of videos exhibiting “discipline,” through the framing of a thin or musical physique, or wealth, made discipline a core value.

The co-opting of discipline to demonstrate external worth has reached its clear nexus. In an age obsessed with the façade of it, a peculiar phenomenon emerges: the rise of Ozempic, also known as Saxenda, a drug which suppresses pleasure for the sake of output. As a weight-loss aid, Ozempic is effective and speedy. As a measure of our values, however, it’s concerning.

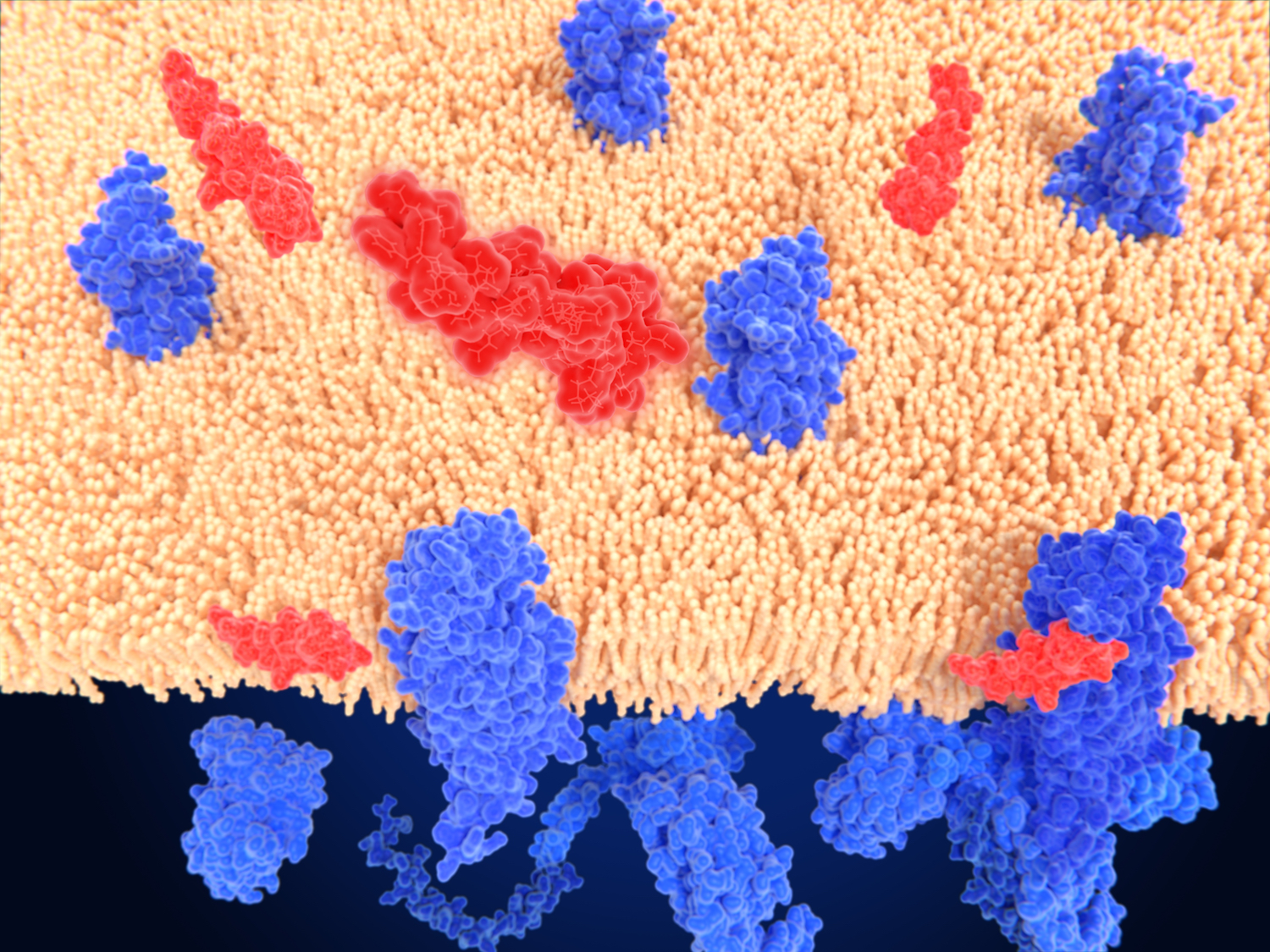

At this point, most know that Ozempic works via semaglutide, which functions by dulling the brain’s pleasure centre via its dopamine pathways, reducing serotonin and other chemicals during all pleasurable activities, not just eating. Ozempic does not “melt” fat, as is often assumed, but disincentivizes the body to eat, causing rapid weight loss. Because we now conflate thinness with personal discipline, we have popularised a drug that makes the body eliminates desire, and in turn reduces the feelings of pleasure one can experience by giving into it. While Ozempic is a medical necessity for many, its commonplace usage for basic weight loss purposes among those who don’t need it tells us a lot about where our culture currently stands.

In an interview with Wired, a researcher who helped pioneer Ozempic, Dr. Jens Holst, said that, for Ozempic users, “once you’ve been on this for a year or two, life is so miserably boring that you can’t stand it any longer.” In many cultural criticisms of the drug, individuals note the collapse of the self love or body positive moment, and fear our regression from the acceptance of all bodies back towards the hierarchical celebration of thin ones.

But perhaps the rise of Ozempic is about more than our relationship to our bodies, but our relationship to completion over creation. Increasingly, output is more important than experience. In other words, we value a results-driven world, rather than a pleasure-driven one. This is the central tenet of Ozempic, but it has also become the central tenet of our culture at large. Nowhere is this more evident than in the arts, where artists, filmmakers, and writers are fighting against another results-driven technological advancement: Artificial Intelligence.

It’s near impossible to scroll through any section of the internet without seeing AI-created content, be it filters which “scan” the face of the user to turn them into anything from a 50s yearbook photo to a viking, to movies replicating the aesthetics of filmmakers like Wes Anderson. These types of computer animated effects or films could take months to make if created by human animators or VFX artists. With AI programs, these pages can produce dozens of videos a day. Its increasingly ubiquitous accessibility disincentivises even the smallest inklings of creative curiosity, begging the question: what is the purpose of art if we don’t enjoy making it?

Being creative, or more specifically creating art, is one of the most accessible pleasure centres of contemporary life. It reduces stress and increases focus, and encapsulates the most important element of pleasure: gratification after a delayed desire or working conditions. To make art is to make something of value out of nothing, which gives people a feeling not only of pleasure, but of worth.

AI has its benefits for content creators, of course. It reduces costs, increases output and provides creators the mental space to increase ideation. But all of these things contribute to the de-valuation of art, turning it into something purely decorative rather than an essential part of the human experience.

There’s plenty of mediocre art made by humans. This assessment is subjective but universal. But mediocre, or even actively bad, human-made art still serves an essential purpose. In the race to demonstrate our self-discipline, to show our worth in a world which cares only about what we appear to have achieved as opposed to what we are seeking to achieve, we have lost the pleasure of looking. If life is about finding ourselves, why are we rushing to do that? If healthy, moderation-based eating is what will fulfil you, why skip to the end, dulling the pleasure we get from it? If we want more art in the world, why not invest in artists and art programs, allowing the human mind to create and expand?

Dulling our ability to feel pleasure, either medically or by valuing the output of “content” over art led by curiosity, only creates an environment in which no one is incentivised to do anything. We are racing to the end point of our desires, only to find that there’s nothing worth finding.

With the technology and access many of us have, we are closer to a pleasure-centred life than any iteration of life before us. Why shirk this opportunity to build a life where the pleasure of living — of making art, of eating food, of working out for the joy of achieving something — is more valued than the pleasure of having achieved something with minimal to no effort.

My year of hedonism was not a sustainable project by any means. After only a few months I reached homeostasis, a balance of pleasure and, yes, discipline. But I learned more about myself and my community that year than any other year of my adulthood. I challenge everyone to make 2024 their year of pleasure, to lean into the parts of pleasure-seeking which are about overcoming a challenge, and to focus on increasing our pleasure centres, not shrinking them.