In the past year, the history of rave culture has undergone something of a critical rediscovery. The Saatchi Gallery presented Sweet Harmony, a retrospective dedicated to the art that emerged from and dealt with the rave scene; the BBC aired artist Jeremy Deller’s film on Britain’s acid house explosion, Everybody in the Place; and the Tate dedicated a retrospective to Mark Leckey, whose film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore looked at the links that bound together UK club culture from northern soul to house.

This rave renaissance is visible in fashion too — streetwear kings Palace’s collections take inspiration from acid house and its descendants, from jungle to garage to grime. Among more obvious nods such as bucket hats, Reebok Classic collaborations and old-school Volkswagen GTi T-shirts, sit more nuanced references. Avirex jackets like those worn by grime artists in the early 00s, emblazoned bombers reminiscent of 90s rave merch and breakbeat soundtracks all hark back to a different era in fashion and music. No matter that many of Palace’s biggest fans would be nowhere near old enough to have participated in these scenes.

Palace’s penchant for the near past doesn’t demonstrate a lack of originality, but rather an innate skill at weaving historical influences into an idealised version of the present. “For me growing up and skateboarding, it wasn’t cool to be into football, or Air Max, or mosh trousers, there was this whole us and them thing happening,” founder Lev Tanju remembers. “I didn’t like that way of thinking. I like it that in England now people don’t think every skateboarder listens to Blink 182 wearing a chain wallet.”

During the lockdown, Gabriel Pluckrose, aka ‘Nugget’, who heads up the design team at Palace, showcased an illustrious collection of garage and jungle records via Instagram stories. Michael Kopelman, who ran The Hideout, Palace’s first UK stockist, remembers former colleague Gabriel as “swimming” in it. “They are all into their music”, he says. This passion is felt in Palace’s clothing and campaigns, whether that be rave-flyer inspired graphics or the track choices on their skate videos.

For Nathalie Khan, a lecturer in fashion history and theory at Central Saint Martins, Palace’s nods to the past chime with Mark Fisher’s idea of ‘hauntology’. Mark argued that since the millennium, cultural production has slowed down, notably in electronic music. Where jungle music had once felt revolutionary and totally futuristic in the 90s, electronic music since the 00s has not. If anything, for Fisher, electronic music has looked back to its old sonic idiosyncrasies, best highlighted by the static crackles of vinyl records and lo-fi production. “Brands such as Palace celebrate a culture that has come to an impasse, which succumbs to what is already apparent in music and fashion elsewhere: a failure of the future,” Nathalie says. By this reckoning, Palace’s VHS-filmed skate videos or the records sold on their website are spectral hankerings for a moment now passed.

What Nathalie pinpoints is a cultural malaise felt by millennials and gen Z. Our hyperconnected world, with its immediate content and fleeting trends, might be addictive, but it’s also a little empty, leaving space for a longing for something perceived as more authentic. “Today, it is in the hands of those from a pre-digital era to educate a younger audience,” curator Tory Turk says. “Nostalgic references play a huge role in the authentication of subcultures in the post-digital age.” According to this reasoning, Palace’s work is drawing on a rich tapestry of scenes that have come and gone — and is joining together with them in a postmodern collage. Homages to the Moschino two-pieces donned by partiers at UK garage nights, rather than being pastiche, are reminders that subculture relies on its forebears. UK garage followed jungle, which itself followed hardcore in an evolving lineage. In a similar way, Palace follows on from Franco Moschino’s work, joyfully reinterpreting prints, turning to history and designing something modern from old references.

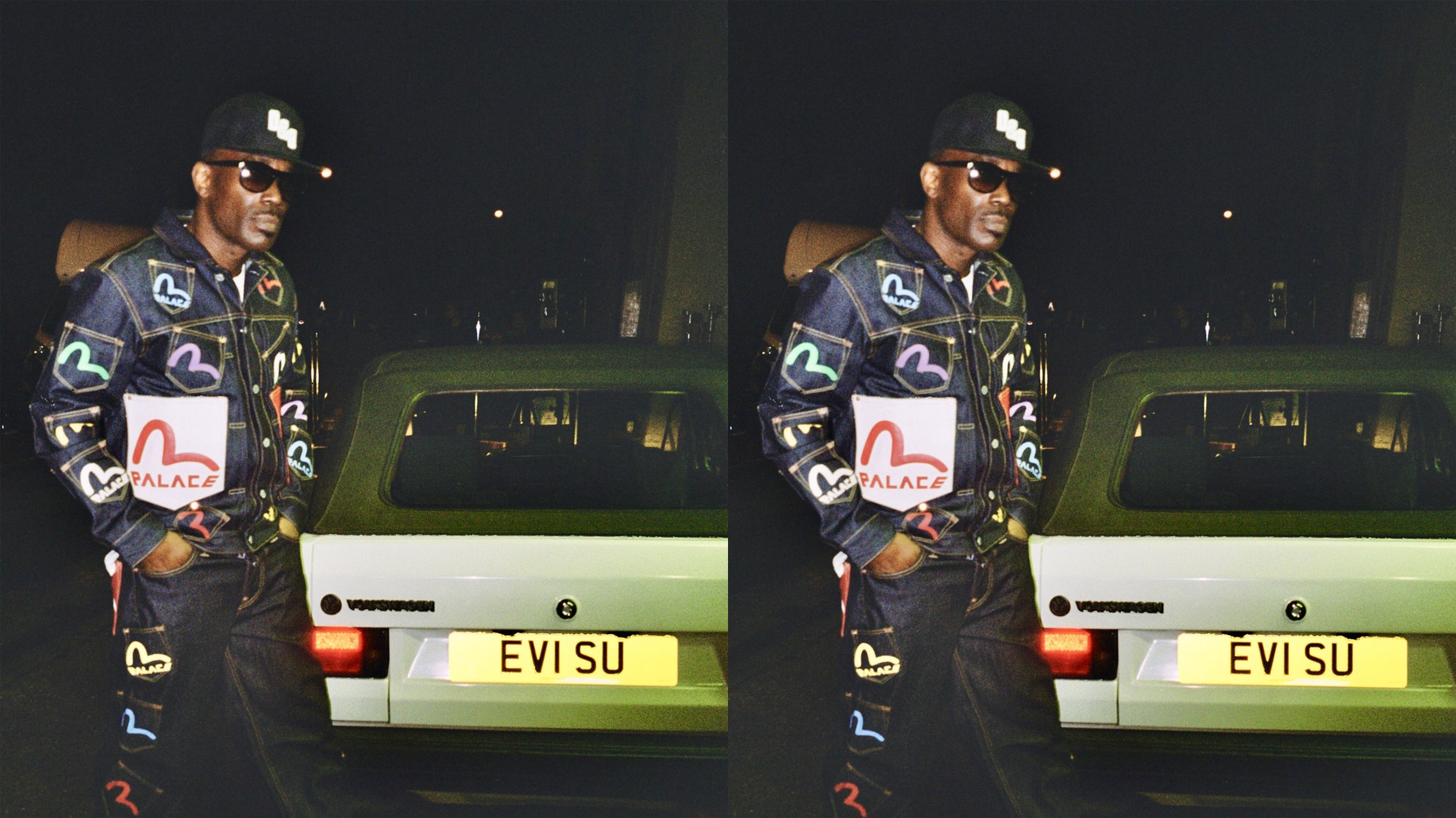

Not that this approach can’t fall flat. “Nowadays, when you see big labels trying to emulate rave fashion, it doesn’t feel genuine, they’ve probably just scrolled past a few Dave Swindells pictures on Pinterest and thought ‘oh let’s try and do that’,” observes 10 Magazine writer Paul Toner. Before releasing their collection with Evisu, Palace teased it on Instagram in a clip heavy with meticulous references confirming that yes, Palace lived this. MC Skibadee freestyling, an old-school car radio tuned into Kool FM and Lucien Clarke requesting “king Rizlas, silver please”.

Palace’s success shows that a brand can achieve mainstream consciousness and retain its underground lustre. After all, they have outfitted Wimbledon tennis players, designed a Juventus football kit and plastered advertisements across London’s taxis, all while paying homage to the niche music and culture they grew up on. Like the pirate radio stations hijacking spots on the airwaves, Palace simply can’t be ignored.

Credits

All images courtesy of Palace