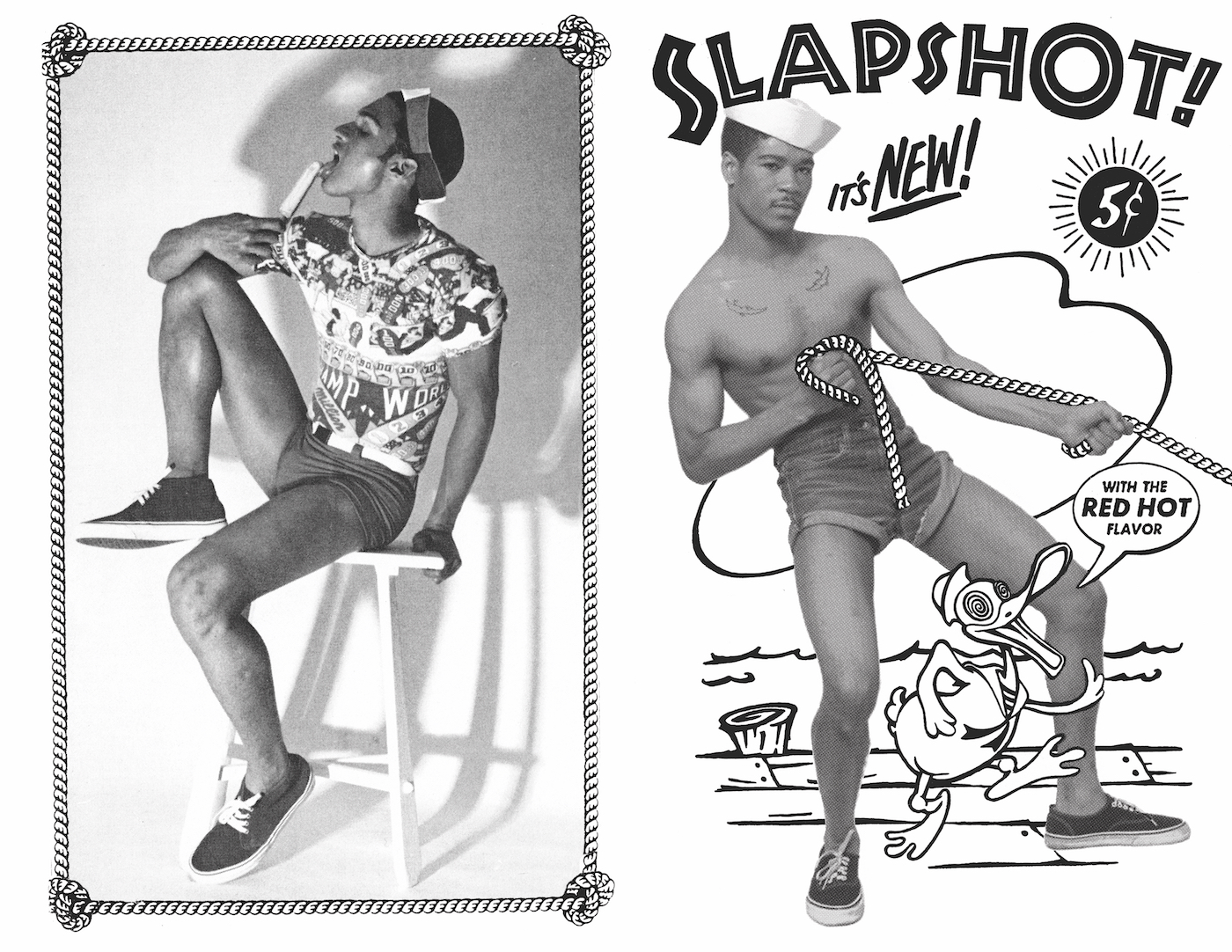

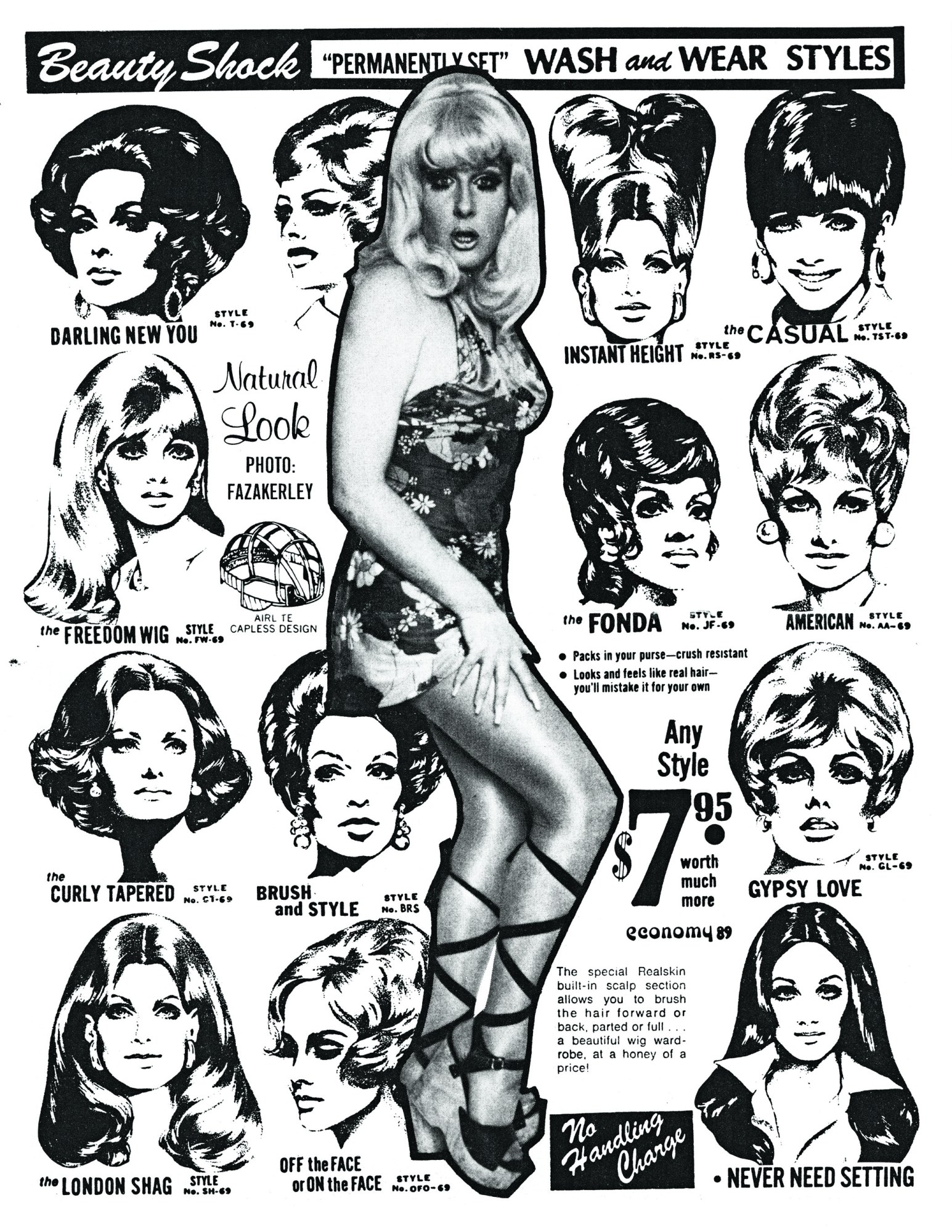

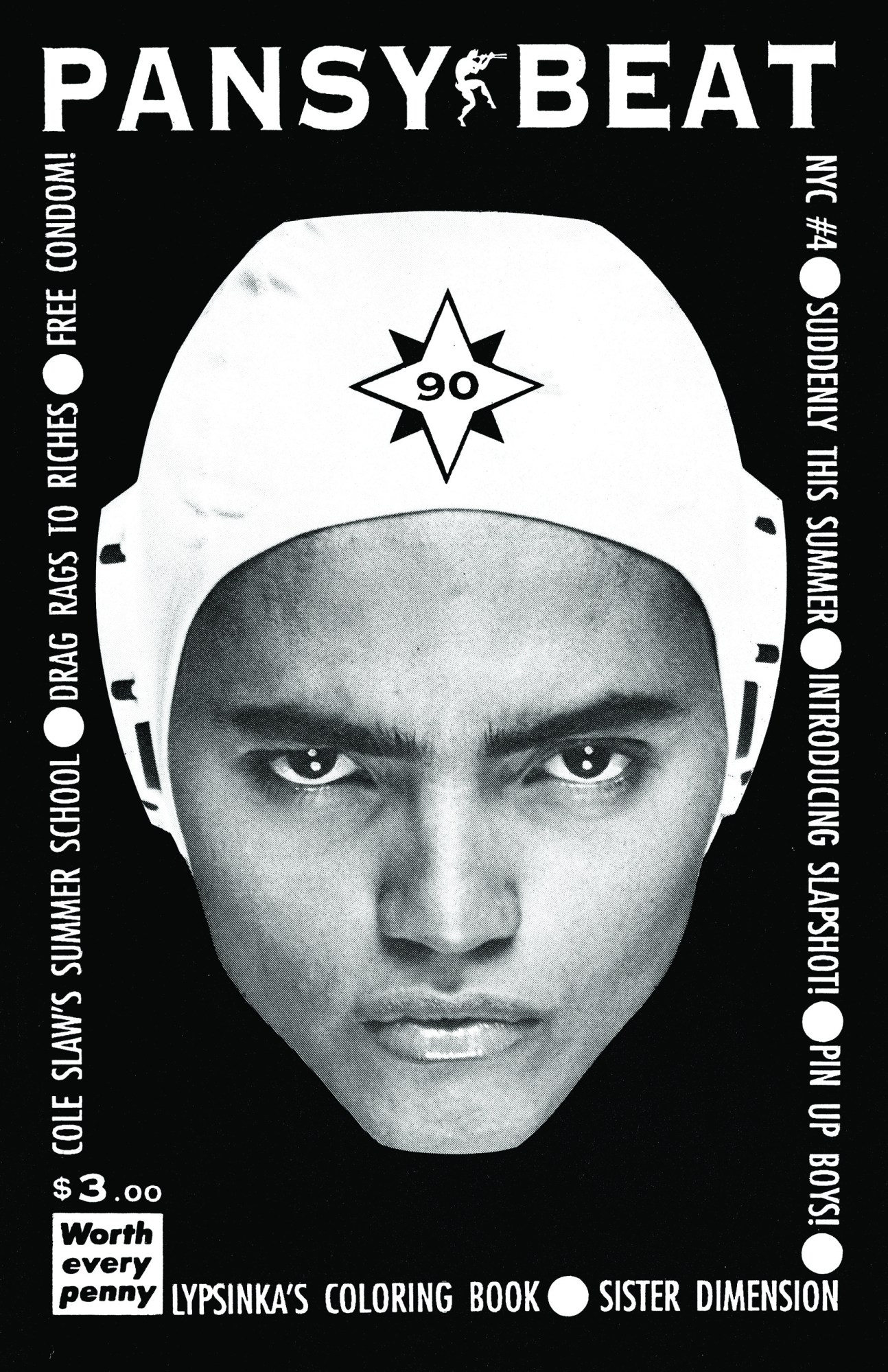

Flipping through the pages of the short-lived East Village quarterly zine Pansy Beat (1989-1990) offers a brilliant glimpse at the joy — and concerns — of queer artists living in the midst of the AIDS crisis. It combats the impression that being queer in NYC in the late 80s was an experience solely defined by illness and death. There was celebration, too: gender-bending club boys wearing heavy eyeliner, underground parties, local queer-owned bookstores. Pansy Beat highlighted this thriving culture, both through its content and ads for emerging “metrosexual” brands and cabaret shows. The zine featured profiles of prominent downtown characters like the iconic drag queen Lady Bunny, in-depth articles on niche topics like the history of false eyelashes, and PSAs about safe sex. Pansy Beat represents a time when queer culture was off-the-wall, subversive, and still evolving.

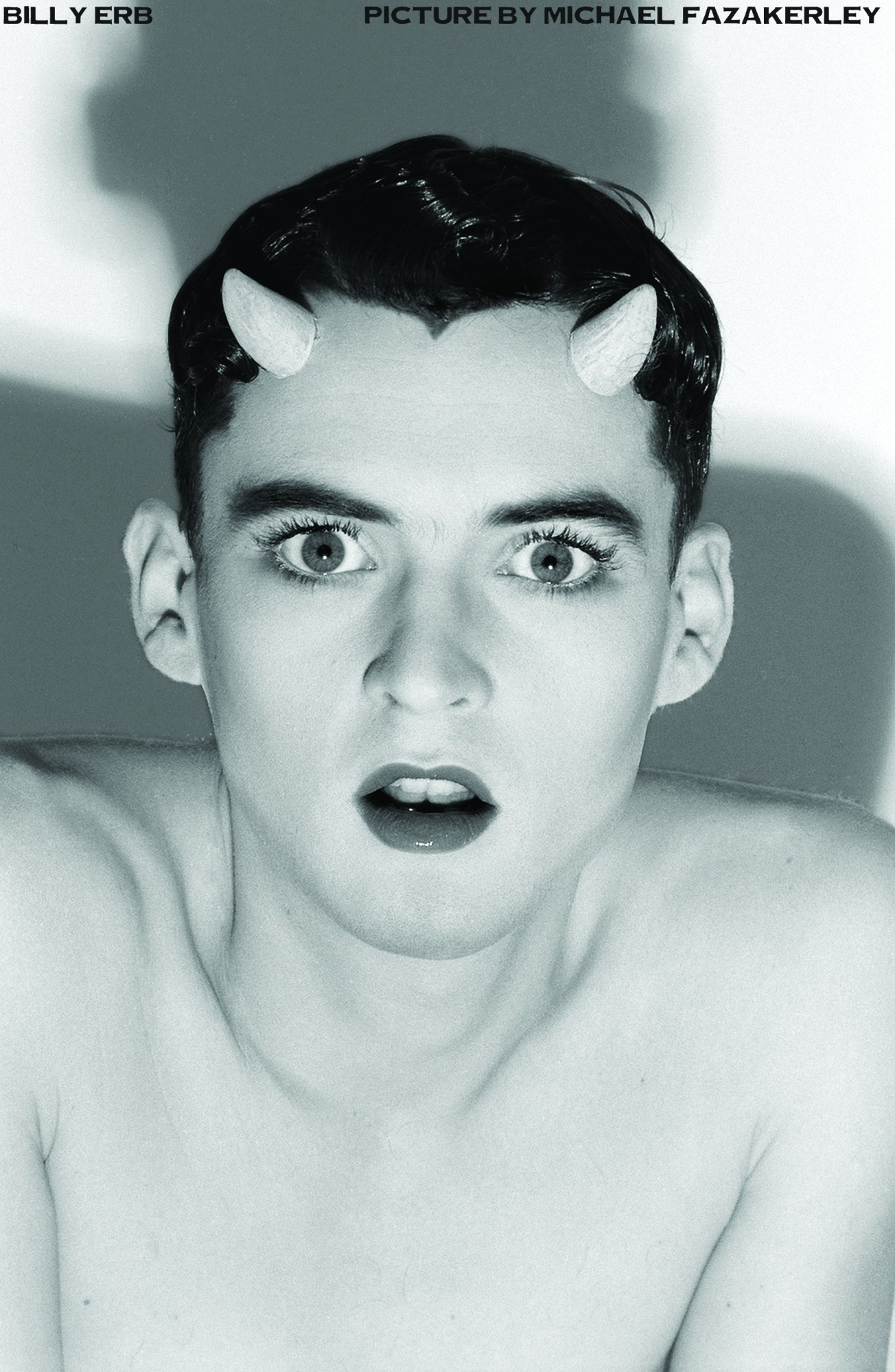

“It was a place to put everything we loved,” Pansy Beat founder and editor Michael Economy tells i-D. “There was so much going on in the East Village at the time — Lady Bunny, the ACT UP movement, the drag performance/art scene.” Pansy Beat was a group effort, Michael says. Collaborating with his friends, the then 29-year-old would stage elaborate photoshoots inside his apartment. “I would feature people I was intrigued by,” he says, explaining how the zine’s timeless glamor shots came together. “For example, I put Billy Erb, who was a pre-club kid, on the cover when I saw him with this third eye on his head and wearing a cape and sky-high boots. I went up to him and said, Who are you!?”

Michael had to put Pansy Beat on permanent hiatus when he ran out of funds in 1990 and had no choice but to get a “real job.” But the zine inspired other queer publications to spring up. One year after Pansy Beat closed, HX — which featured listings of gay clubs and interviews with go-go boys and drag queens — arrived on the scene. A friend once told Michael that during the early years of OUT magazine, editors would refer to old copies of Pansy for inspiration.

Michael recently collaborated with artist Jan Wandrag to release a collector’s edition box set of Pansy Beat’s too-short print run. Here, he talks to i-D about the practicalities of putting together a seminal queer zine with no budget and the influence of the AIDS crisis on his life and work.

How did Pansy Beat get started?

We were kind of inspired by Linda Simpson’s zine My Comrade. I heard about it when I moved back to the East Village after living in Tokyo for a year. I was hanging out with my two friends and they were just catching me up on the East Village news. A lot of them were asking me what I was going to do next. Then, one of them grabbed the copy of My Comrade I was holding out of my hands and said, I know what you’re gonna do. You’re gonna make a zine and put me on the cover! And that was the match that started the fire.

The zine is filled with insider East Village knowledge and niche topics. There’s a critical essay about Judy Garland’s later years and a history of false eyelashes. How did you approach curating your stories?

In the beginning, I just got my friends involved and asked them to contribute. I told everyone they had to sell at least one ad. Because even though printing costs were so low back then, we still didn’t have enough money to print as many copies as we wanted. I was pretty much the publisher, editor, and creative director. Before Pansy Beat, I worked at Paper for two years during their very beginning — so I got a lot of experience from that. I remember, I was friends with the designer André Walker and he introduced me to Kim Hastreiter [co-founder and co-Editor in Chief of Paper]. It was great prep. We would walk around the East Village and hand out copies of Paper‘s first issues.

And I saw there were actual condoms placed inside the zines, to promote safe sex. How did the AIDS crisis influence Pansy Beat ’s content?

Yes! The New York Board of Health reached out to us about the condoms. My friend and contributor Terry, who went by the name Coleslaw, facilitated that. When we got the box of condoms, I thought, Why don’t we use double-stick tape and put them in the magazine?

In terms of AIDS, Glenn Belverio mainly wrote the political content for the zine. Other than that, our main intention was to be really — I don’t know how to say it any other way — but just “unashamed sissy shit.” We weren’t really trying to be political. We just wanted to hold up the people we knew in the neighborhood and loved.

But surely AIDS must have touched your life in a personal way?

Yes. Honestly, it’s taken me 27 years for me look back on all the friends I’ve lost and how everyone I know also lost friends. Downtown Manhattan was really a ground zero for AIDS. And sometimes I think the general population doesn’t really understand that. Now, I look back on it and see it in a way I never saw it before. It informed so much of the way me and my friends were in the world.

How does it feel to look back on those years? Did you ever imagine the zine would still be culturally significant almost three decades later?

To me, it’s not so much nostalgia as it is this thing I did with my friends. The zine took so much work and it really did take over my life for a year and a half. Then it just ended. (Because I got evicted from my rent control apartment and had to get a real job!) Looking back, I felt like it deserved to be put back in the world again for a new generation of people. Because, culturally, there is a bit of hole regarding what happened during those years in the queer scene. Because so many people passed away from AIDS. And there were so many people not around to help grow the culture — influential artists like Keith Haring passing away during their prime. So things really did go in a different direction.