According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the word of 2025 was “parasocial.” Over at the OED, it was “rage bait.” Merriam-Webster, meanwhile, chose “slop.” But if all of these descriptors capture how we all lived very online in 2025, it feels like the literal wordsmiths are missing a trick. The word that feels heavy in rotation this year? “Performative.”

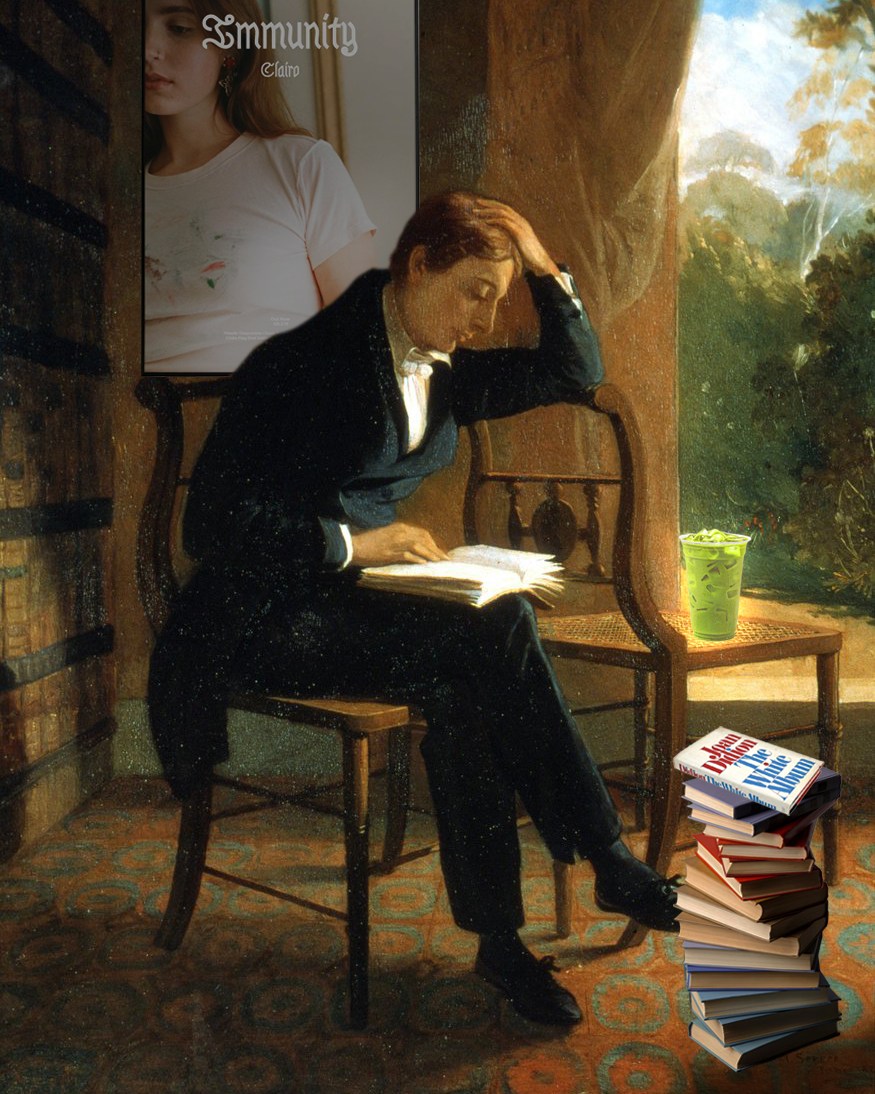

Google searches for “performative” increased throughout the year, peaking in September and again in November. That may be down to the way the word has been paired with others to create online archetypes. Take the problematic favorite, the performative male, out to get women by pretending to love Sade and loudly proclaiming his feminist views on TikTok. Or “performative reading,” a very real phenomenon in a post-BookTok world. It isn’t just an online term, either. “Performative” has become part of group chats and IRL conversations too, more often than not accompanied by an eye roll.

Perhaps “performative” resonates because it works as a shortcut. It describes a world where we curate everything we do in order to post it on social media, while also being hyper-aware that everyone else is doing exactly the same thing. Calling something “performative” is often accurate, but it’s also a little judgmental.

J’Nae Phillips, who writes the Fashion Tingz Substack about online and offline trends, has noticed the uptick. “It’s now used to call out behavior that feels calculated, insincere, or optimized for an audience,” she says. “As more of life is documented or broadcast online, people seem increasingly quick to label something as performative if it appears curated rather than authentic.”

Curated rather than authentic is, of course, a familiar state for most of us. Who doesn’t have 12 shots of their dinner, book stack, sunset, or cat sitting in their camera roll, all in pursuit of the perfect but not-too-perfect image for Stories?

Tony Thorne, founder of the Slang and New Language Archive at King’s College London, says the rise of “performative” is a perfect example of how language reflects how we live. “It’s what they call a paradigm shift, when something suddenly becomes crucial or all-pervasive,” he says, noting that his “online all the time” 18-year-old daughter, Daisy, uses the term often. “I think that’s what’s happening. We’ve reached a tipping point where being online and offline has really merged.”

As with most words, Thorne says, the meaning of “performative” has changed over time. In the 1950s, linguists used it to describe “performative speech acts,” moments when language itself carries special weight, such as saying “I do” at a wedding. Later, the word became associated with the performing arts. Its meaning began to shift again in the mid-1990s, arguably alongside the rise of the World Wide Web. After a brief stint in corporate culture in the 2000s, when “performative” could be used as a kind of bro-to-bro compliment after nailing a presentation, the word settled into its current meaning.

Phillips believes the term’s popularity now signals a “cultural shift toward meta-awareness.” “People aren’t just posting, they’re analyzing how everyone posts, and why,” she says. “The word has become a shorthand for our collective skepticism about authenticity in digital spaces.”

Those digital spaces are also changing how we speak. Thorne, possibly the most online baby boomer ever, argues that the dominance of internet language over the past few years proves the point. “Slang used to come from gangs, school playgrounds, or groups like soldiers or taxi drivers,” he says. “Now a lot of slang isn’t coming from the street. It’s created, curated, and disseminated by people looking for influence and attention. For me, it’s fascinating.”

Phillips suggests several other online favorites as contenders for word of the year, from “delulu” to “situationship” to “NPC,” short for non-player character, used to describe people whose behavior seems scripted or unoriginal. “These words thrive for the same reason ‘performative’ does,” she says. “They help people describe the emotional and social complexities of living life half-online, half-offline.”

Perhaps “performative” rises to the top because it aligns with a hypocrisy we’ve grown used to. It describes attention-seeking behavior, but using the word, and the judgment it carries, can be attention-seeking too. As a cultural descriptor, Phillips says, it captures “the anxiety around authenticity in a hyper-visible, algorithmically shaped world.”

And even if it isn’t officially the word of the year, “performative” sits neatly alongside the ones that are, particularly “rage bait.” Thorne notes that the term overlaps with what is sometimes called “performative cruelty,” a strategy used by figures like Donald Trump and political movements such as Reform online. “It’s toxicity where you’re only trying to provoke and condemn and incite and hurt and frighten,” he says.

Ultimately, Thorne emphasizes that all of these words, from “rage bait” to “slop” to “performative,” matter. “Older people often look at words of the year and say, ‘Oh, there’s another silly, exotic, alien term,’” he says. “But these words actually mean something quite important. They’re very resonant.”

Everything Is Performative Now

A year ago, “performative” was mostly attached to specific archetypes or habits. Now it’s become cultural shorthand.

Loading