There’s an image towards the middle of Petra Collins’s new book — the latest edition of cult erotic magazine series Baron — that she believes conveys nearly all the different emotions behind the entire book. Her sister, Anna, sits at the wheel of her car driving through their childhood neighbourhood in Toronto, her eyes focused on the road, a silicone casting of Petra’s face resting upon her own. “It’s so unsettling, yet it’s also so beautiful and calm,” Petra says, looking at the image on her laptop and describing it over the phone. “There isn’t anything hectic about it, it’s very serene,” she adds. “I love it because of this calm, which is something that I rarely experience. And it feels very safe to me, because it’s my sister in it, and it’s also me.”

Petra’s edition of Baron, entitled Miért vagy te, ha lehetsz én is?, is her latest in a series of proverbial exorcisms. “A big part of taking photos for me is it’s a form of therapy,” she says. “I have all these things in my head which I need to get out.” Shot over the course of a year, the different casts of her body — courtesy of artist Sarah Sitkin — are placed against backdrops significant to her childhood and adolescence; some in a studio made to look like her childhood bedroom, others in and around Toronto. “The book deals a lot with my body in relation to sexuality, so I sort of placed it in fantasies, or childhood fantasies,” she says. “Nothing really shocks me or shocks anyone these days, but seeing a real cast of my body and different parts about myself for the first time was crazy. You can see every pore, every vein.”

It’s arguably her most ambitious project to date, marking a new era in her already expansive career by framing herself — or at least a silicone rendition of herself — as the subject of her own photos. The name alone, drawing on her family’s Hungarian ancestry and translating as “Why be you, when you can be me?”, immediately singles it out as something more autobiographical. Having spent the last decade capturing the coming of age of her peers with a level of insight only afforded to those maturing at the same pace as their subjects, Petra is now turning her camera onto, and into, herself. As she does, her work edges closer to darker, more surreal places.

“For me, I really don’t even really think I’m capturing the surreal… it feels real,” she says. “I really think that we’re living in a time when you can live in so many different realities.” The tension between the real and the surreal is something Petra has always been fascinated by, and continues to inspire her work. Her work on the pages of Baron sees these ideas reach their climax.

You describe this issue of Baron as investigating “the evolvement of today’s image sharing society and whether this is changing our relationship to ourselves and the world” — can you explain this a bit more?

I’ve been doing photography for a long time, which is crazy. I’m 26 and I started when I was 15. The way that we see and photograph ourselves has changed so much since then, so it’s interesting for me going back to that, because I guess when I started taking photos, I was really obsessed with selfie culture, but it was only just starting up. This was before Facetune or any of those apps, so it was really just everyone discovering how they can insert themselves into this other reality, and I guess create their own sort of landscape. So fast-forwarding to now… I think it’s gotten to an extreme, with our online selves, where we have begun to lose our sense of reality.

Literally nothing is real anymore. You just don’t know… everyone’s Facetuned, everyone’s physically changing their faces. A.I. models exist. I find it funny a lot of times when I’m asked to take photos or shoot campaigns, people are always like, ‘oh can you do something that’s real, we’re want something real and authentic.’ I want to say that nothing is real or authentic anymore. So that’s sort of where my work comes from, that’s my reality.

Tell us about a bit about making moulds of your body. Why did you decide to do this and what did it help you achieve?

I was like, how can I get to another level where I can photograph myself, but also be removed from it? I ended up working with this artist that I love, called Sarah Sitkin. She makes these really beautiful body suits. They really moved me. She casts people in silicone and makes these literal suits that you can put on. I then decided I would make my own body so I could physically remove myself, but also place myself back into places that — in my mind — I needed to go back to. Or like, dreams that I sort of needed to deal with it.

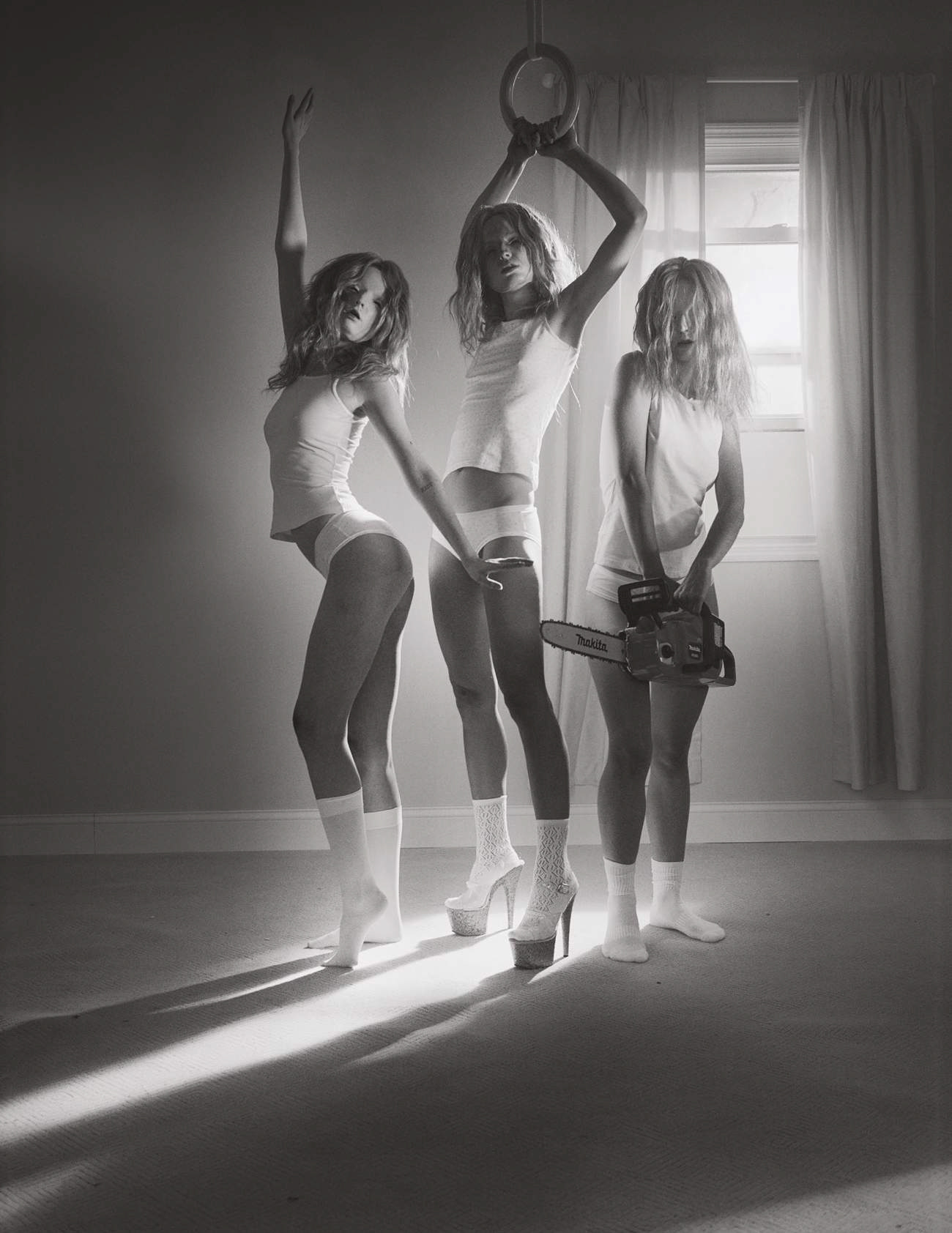

I took my body back to my hometown. Half of it is shot in Toronto, and half of it is shot on set — so the stuff in Toronto is where my sister and dad live, it’s at my old high school, it’s just around places that I grew up. We built the set inspired by my childhood bedroom where I have those three girls wearing my masks — three versions of me — and we ended up taking the set and submerging it in water. The other aspect is that I grew up in the suburbs for a tiny bit, but I’ve always had such a big fantasy around that, as do a lot of people. It’s such a big theme in movies that I love, the emptiness of suburban life.

What was the experience of putting yourself, or a version of yourself, back into those familiar territories?

This is a point I’ve been going back and forth with a lot in some of my newer work. I’ve had a lot of people say it’s very surreal, “you’re working in the surreal now”, but for me it feels like… I don’t know what real is anymore, and I don’t know if any of us knows what real is anymore. I don’t think we can identify what anyone looks like. This is my style of documentary now, because I’m just documenting my mind.

But you’ve never really worked with self-portraiture before…

No, but it’s funny because a lot of people think I do self-portraiture, but I don’t. I’ve never done. For me, I love working with subjects, but it was really fun being able to see myself through the camera.

Is this project a reflection of the direction your work is moving in now, towards a darker place?

For sure. My work has always come out of my pain, and it’s always been a little dark, but I think now — because I am the subject of it, I really get to take liberties. Because when I’m shooting other subjects, obviously I love get dark, but I always want to stay true to their reality, whatever that looks like, so it doesn’t necessarily reflect the darkness that I really want to explore. So, to answer your question, yes! This is sort of a prelude to then me directing horrors, because that is what I’m going to do. It’s my favourite genre, and over the past year I’ve been writing a feature with my writing partner Melissa.

Your sister plays a big role in the images.

My sister is the closest to me, but she’s also the person who grew up with me and we shared a lot of the same — not that we wanted to — the same body dysmorphia. We’re pretty close in age, about two-and-a-half years apart, so we were going through puberty at around the same time and had very similar traumas. I guess we grew up in a household where reality was always in question, we didn’t necessarily know what real was. Both of us are like storykeepers to one another, she validates or just kind of helps me know what was real, and I also do that for her. So, it’s another thing that has kind of been a theme throughout this: reality.

[My parents] struggled with a lot, and reality was kind of always in question. My sister and I growing up under that, growing up questioning what was real and what wasn’t: it was very confusing, but it also, I think, fostered creativity. [My parents] come from really crazy, immigrant backgrounds, where they also didn’t necessarily experience anything that felt true. My mom came from Hungary, she basically came a year before the wall fell, so a big thing for her was… you couldn’t trust anyone, all the phones were tapped… friends would rat friends out, that sort of thing.

What’s changed most in the last decade?

When I first started taking photos, I was really documenting young girls, and for me as a young woman, I was really in it, and I was able to do that. It was also in a time where, yes there was social media, and people did exist on the internet, but it wasn’t at the degree we’re at now. If I approached taking photos the same way I did 10 years ago, it just wouldn’t be the same. It just wouldn’t. Because our internet presence has become almost greater than ourselves… I think there’s a different way to capture to what is real.

Instead of thinking, I’m going to shoot what you’re physically doing, which is very surface, I’m going to shoot what is internal for you, what’s the reality that you see as real. Very rarely are you able to make imagery or take imagery that reflects your inside, or what you’re seeing. I mean, again, going back to the word exorcism, it’s literally the most satisfying thing ever. It’s what every artist via a different medium experiences, when you’re able to get the internal out externally, it’s so gratifying.

Do you still get photographs back from the lab and find yourself surprised at what you were able to do?

Every time. I’m like, ok this is where I’m at, I thought I was somewhere else, but this is where I’m at. It’s shocking every time and it’s so satisfying every time and it’s something that’s never going to be finished. When I was taking these photos, it’s just funny what you end up seeing; it’s never what you thought.

Baron by Petra Collins is available to pre-order now.

Credits

Photography Petra Collins. Courtesy of Baron.