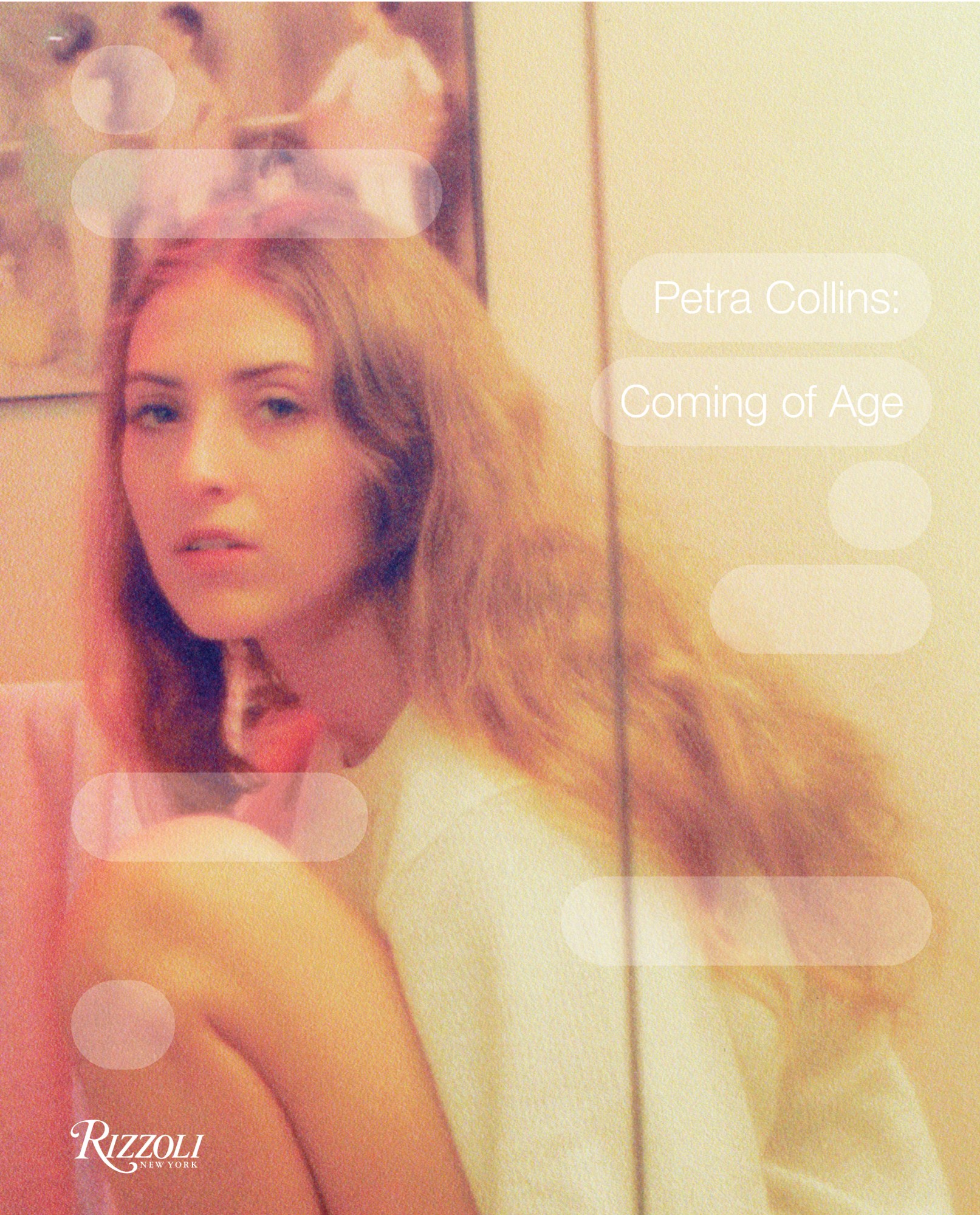

We’re at Dimes, and Petra Collins is devouring a bagel. It’s unseasonably freezing outside and we’re both wearing puffers. On the table between us is Coming of Age, her new book with Rizzoli, which traces her own coming of age as a photographer while also addressing the topic at large. It is destined to become a classic, like something Francesca Woodman might have published if she’d had good meds and good Internet.

“This book is extremely personal, but I hope when you look at it you can see yourself in it, too,” Petra writes in the introduction. She’s a brilliant, direct writer, despite the dyslexia that made school difficult for her. It’s all part of communicating to the hundreds of thousands of people — many of them young girls — who follow her.

The first photographs in the book were taken when Petra was just 15 and reeling from the knee surgery that ended her ballet aspirations. “That to me was so devastating because I was my body and having that taken away from me was an awful experience, but because of that I ended up picking up a camera,” she says. Flipping through the early photos, Petra says, “I actually really miss this darkness. The light was more transitional.” Now she’s known for a vibrantly saturated color palette.

Growing up, her main interest was film, but photography “was the easiest thing as a young woman.” The movies that obsessed her then and now are visible in every picture she takes, with their cinematic crops on moments that are both painful and pretty. She’s always liked horror films that happen in the suburbs, “where it’s a safe place but really not,” which should tell you a lot about her worldview. The deceptively ornamental Czech new wave film Daisies is another influence. If you’ve been taking Petra’s photos at face value, you haven’t been looking closely enough.

Petra has always been suspicious of the superficial. She was a ballerina, and then it ended. She grew up in a beautiful house in the suburbs, and then her family lost it in a difficult time. But even when she was still living in Toronto’s suburban idyll, she saw the pathos in perfection. “We lived in this cul-de-sac and I couldn’t walk anywhere alone, so it was this place of such isolation but zero freedom,” she remembers. In that bubble, she took pictures of her friends and her sister, fervent images of girls contained in bedrooms and backyards and school hallways.

“I always wanted to make things that were beautiful to look at but maybe a little violent or scary or not very digestible,” she says. That explains pictures like a cheerleader bathing in a red substance that might be blood; a close-up of a wet t-shirt that implicates the male gaze; a series of extreme zooms on girls in mental distress.

A recurring Petra signature is the closeness of her crop, as close as an arm is for a selfie. She doesn’t feel any distance from her subjects, she tells me: “Photography is so intimate and personal for me.” When she took one of those first photos, of a group of girls talking on a bed, she felt an immediate sense of how her closeness to subjects could be powerful. “The conversation was very dark and it was about boys and their bodies and I was really taking that on and when I got the photos back they were not what I expected at all,” she remembers. “That’s when I realized how powerful I could be behind the camera and how powerful the camera could be to me.”

That kind of deep empathy can be exhausting. “After I shoot I like to be by myself and stay super silent because I love it so much and it’s something that comes from my gut,” she says, gesturing to her stomach like the dancer she was. When I mention that it sounds like being a therapist she agrees: “I guess it is like either going to therapy or being a therapist, but it’s like my whole body and mind just want to go to sleep.”

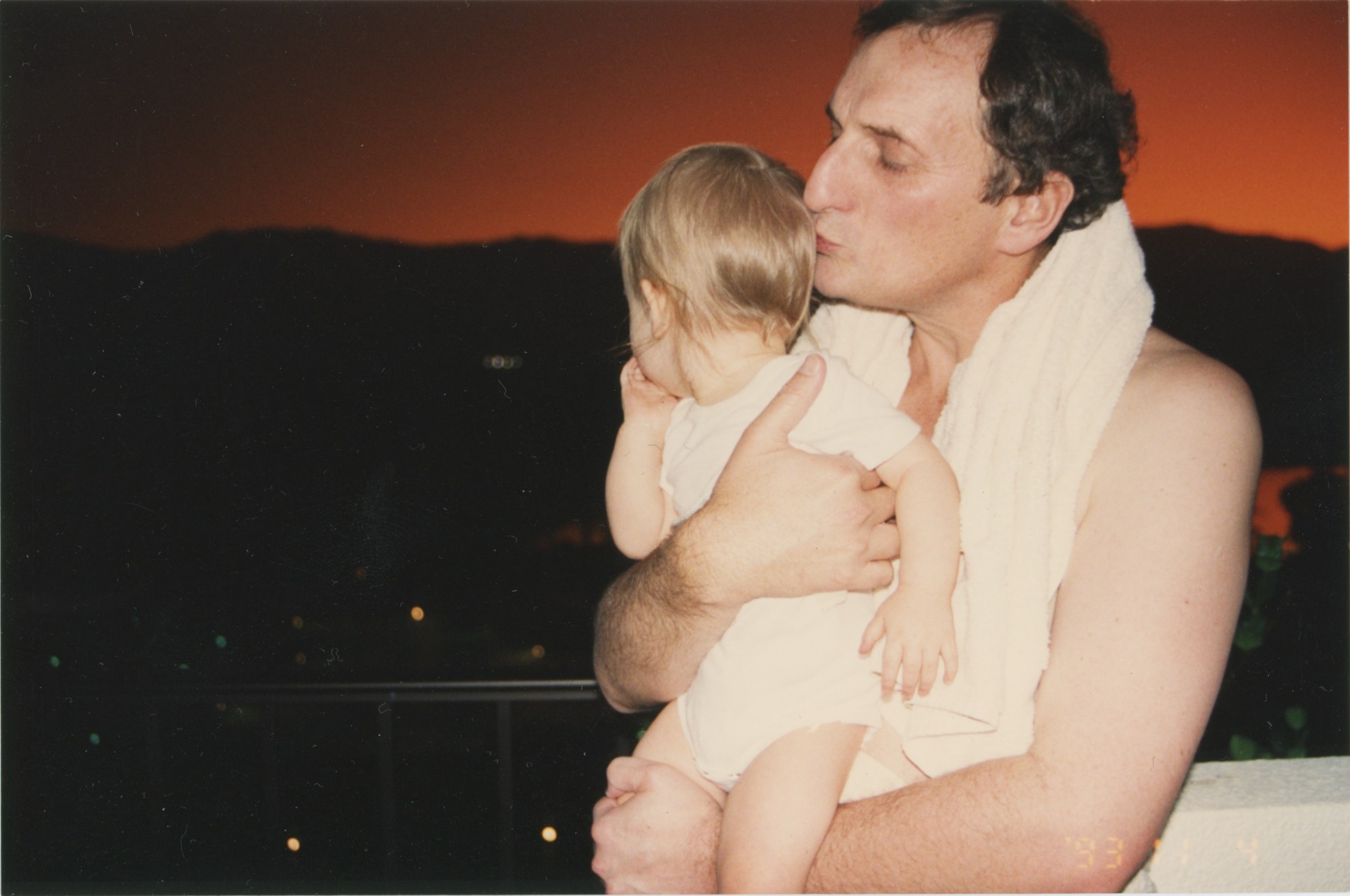

She’s been exploring the depths of emotion recently with Selena Gomez, another artist who is familiar with what the world expects from talented young women. There’s a true kinship there, and the pair has been reading up on film theory with the idea of doing a feature together. For her music video for Selena’s song “Fetish,” Petra was inspired by the breakdown scene from the 1981 film Possession. “She basically ends up fully losing it but it’s this crazy primal experience and it was so powerful for me to watch,” she says. “I feel like it’s powerful to see someone who also struggles and has problems. You need that sadness and anger to be happy.” And we need female artists to explore that kind of dimensionality from within. The scrapbooked style of the book lets Petra open up her world. There are handwritten letters from young girls, scanned Polaroids, and most tellingly, family photos. In one picture, Petra and her sister stare intently into a dollhouse. In several, Petra’s back is to the camera. Even as a kid, there was that tension between being a subject and being an observer.

Her art is about crystallizing that observational power. But people are interested in Petra as a subject, too. She’s appeared in Gucci perfume ads, and on magazine covers. She also went on one of Ryan McGinley’s legendary road trips, where she seems to have recaptured some of the confidence that ballet and adolescence stripped away. “That was one of the most important trips of my life because I was in a very bad place and also I have serious body dysmorphia,” she says now. “There’s not anything that’s sexual about his photos, we’re just parts of nature doing the craziest things. That was so powerful for me because I’d never been shot like that or seen like that.”

So is Petra still coming of age? “Yeah, one, hundred percent,” she says. “I’m still learning to process the damage that I’ve done to my body and others have done to my body. I’m changing and learning every day but I don’t feel like it’s done, I still have a lot of work to do.”