Philipp Ebeling grew up in a small town of 2,000 people in Germany. When he first arrived in London at age 19, he recalls how amazed he was at the size and scale of the city, and eventually made it his home. Now, almost two decades later, he’s turned his love of the city in a new photobook, London Ends, a document of the city’s fringes.

London Ends — despite being a visual masterpiece stuffed full of amazing sights, scenes, and people — is also part of a new narrative of London. Gentrification, rising house prices, and increased costs of living have pushed the “center” ever outwards. The fringes are becoming increasingly important: diverse, multiplicitous, full of unexpected clashes. They’re real, unvarnished, devoid of tourists and landmarks. They’re spaces of communities and residents, an uneasy balance between the forgotten and the future.

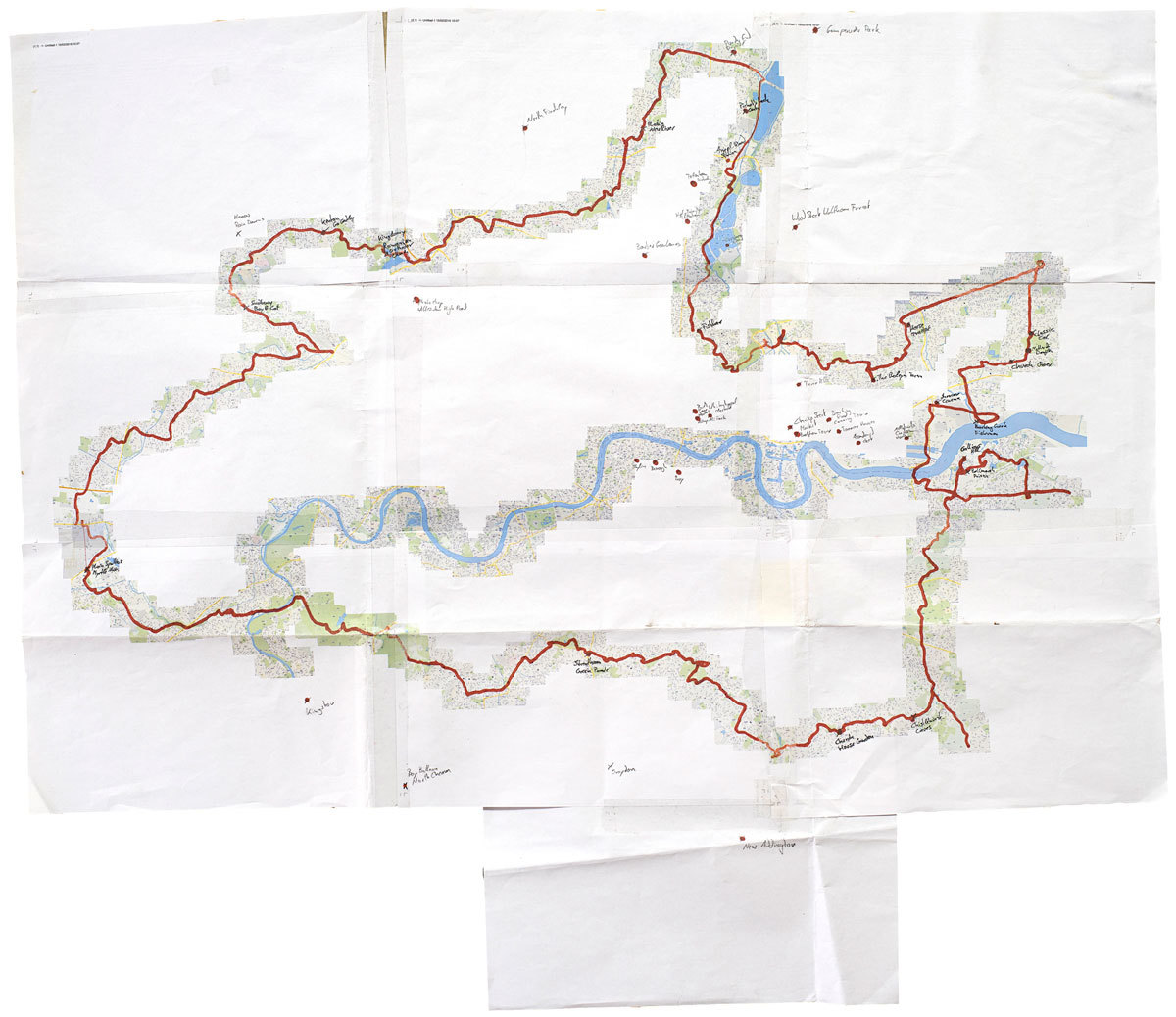

London Ends is a document of all this. Having photographed the city and its inhabitants for years, Philipp decided to set off on a 10 day long, 155 mile walk around London, a journey to capture and document the new center of the city.

Congratulations on the book, it looks really great. What were your first impressions of London when you arrived here from Germany?

London Ends was born from many years of not only living in London, but also photographing it. I came to London when I was 19, all those years ago, and I remember being amazed and overwhelmed. I grew up in a small village in Germany of 2,000 people. I went traveling and ended up in London almost by accident. I fell in love with the place, and decided to stay. For awhile I was just exploring the city, getting lost, finding everything incredible. I wasn’t really taking pictures at the time. I started photographing London almost by accident; one day there was a big snow storm outside my house in Whitechapel which I shot. The pictures ended up in the paper, and from that I started getting jobs photographing random bits of London.

I started to realize that there’s quite a common narrative to all these fringes, these bits of London; they’re constantly changing, they’re slightly overlooked, they’re a little rundown. They’re not quite suburbs but they’re not quite inner city areas either. From thinking about what these places have in common, and finding that narrative arc, I decided to walk around London.

Not growing up in London, coming here as an outsider, has it affected the way you work?

I find it hard it to be a complete outsider and do meaningful work, because I feel like I’m intruding. I need that knowledge of the place, otherwise I feel like I’m imposing my story on it. I need to know places. My first book, for instance, was about the town I grew up in. It’s about finding a middle ground between insider and outsider. I know London quite well, which I find helps for making pictures, but at the same time to make the pictures interesting you always to have find some sort of distance, some sort of angle.

What do you hope the book says about these areas?

My feeling is that there’s been a shift in the narrative of these areas as they become more important. The pressure on housing in London and the way the city is growing means the center of the city, which used to be the countercultural center as well, has become too expensive. People don’t really live there anymore. I’m not too political about this, this is what happens in cities now, it’s partly out of our control. But it does mean the narrative of London is changing, and this work, hopefully, is part of that.

How did you approach it aesthetically?

I try to start with the idea of people in a space, it’s never about a straight forward portrait though. Even if I approach someone and ask to take their picture, it’s more about how they interact with their environment. Then as I came to put the book together, I ended up adding more landscapes in, and I never intended to do landscapes. But it’s a different way of documenting the city.

What were the inspirations for the project, specifically the walk?

Well Ian Sinclair is one. He walked the M25 of course, and I’ve been to many of the places he mentions in that book, but especially the way he uses the M25 as a narrative device to talk about all those areas. Although I find his writing a bit hard to get through, but maybe that’s just because I’m a foreigner.

What about the walk specifically? How did you formulate it.

I made it up as I went along really. I knew the areas I wanted to go through; to the Olympic Park, to Romford, I wanted to cross the Thames at the foot tunnel, which I’d never been to before, I knew I wanted to go to the Thamesmead Estate, where Stanley Kubrick filmed A Clockwork Orange. The place where all the plane-spotters hang out near Heathrow. It’s a very London space, that one.

Then also, we had to plan were we would stay each night, because we wanted to stay with families as we made our way around the city. So that also dictated, to a degree, the route.

What was the walk itself like? Was was the most surprising encounter you had?

On the second day it was raining so hard, there’s a picture in the book I took then, of a dressed-up horse in a horse box covered in Indian-style dress, for an Indian wedding. I sprinted across the road, to take shelter near the horse box. And there was a white man from Essex, who was the horse handler. That felt very typically London to me, that exchange.

Then a little later that day, we were walking, and it was still raining, and we came across this white tent, and it turned out, it was the Indian wedding going on. So we came in and took shelter there. We ended up on stage with this 11- or 12-year-old child, we realized it wasn’t a wedding, but a coming of age ceremony, sort of like a Bah Mitzvah. But what a trip, all these things rubbing up against each other. It’s beautiful that aspect of London. And then it turned that all these guests, also spoke German.

One thing that’s really interesting are the way you combine the pictures with your own words and observations. What drew you to that?

After I finished the walk, I ended up, naturally, feeling like I should’ve taken pictures of some things, or better pictures of others, so I decided to just try and write an account of the walk. I’ve never worked with words before, but I found it interesting, if difficult. Words can be strong, and bring their own associations and meanings, in way pictures don’t. The only thing I tried to avoid was using the words to be illustrative of the pictures actually in the book. I enjoyed the challenge.

What specific images are particularly fond of? Or encapsulate the feeling of the project?

There’s one that’s a good introduction to the book, with the motorway in the background, a train station, a woman with a pink handbag who looks very misplaced in the landscape. That very much sums it up.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography © Philipp Ebeling