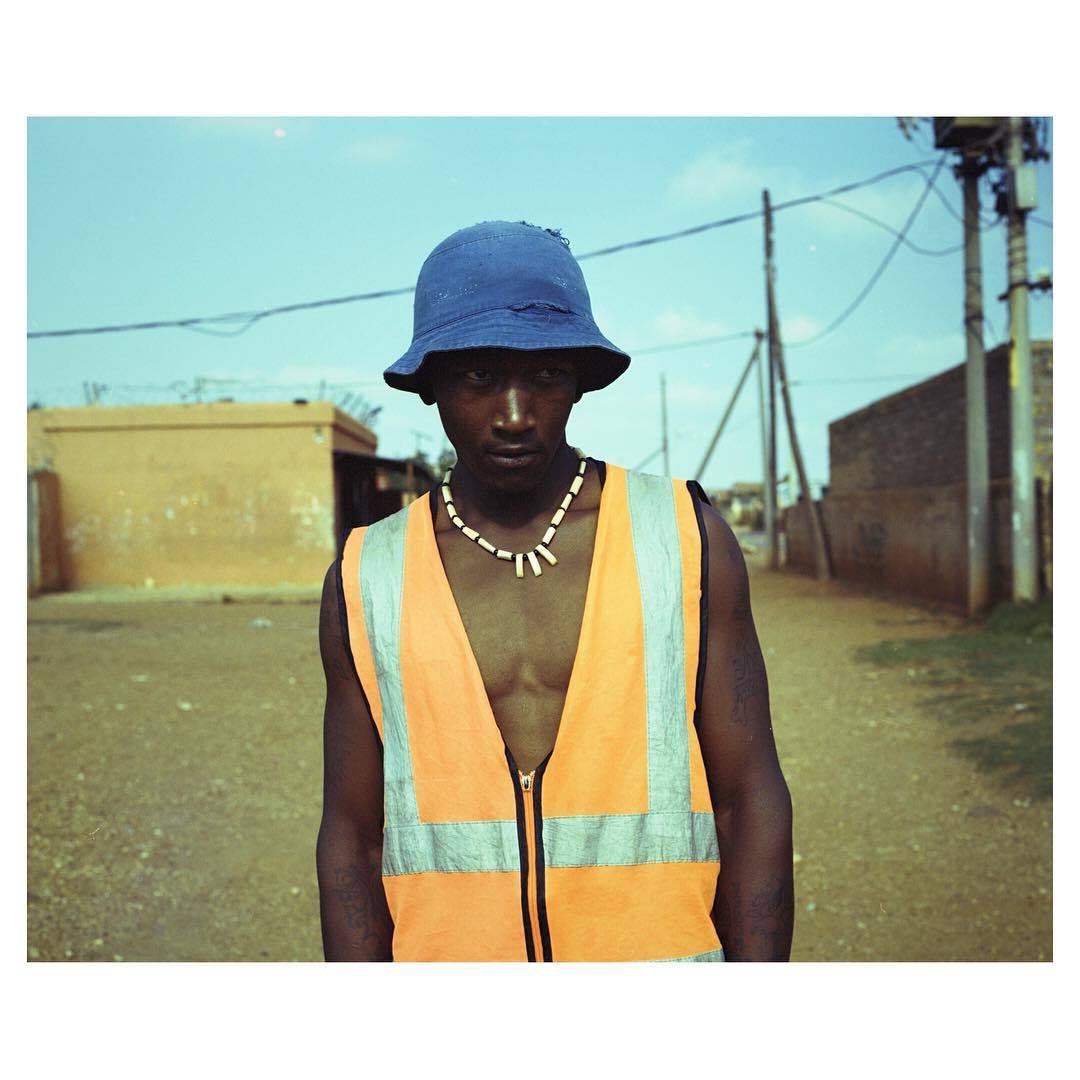

South African photographer Andile Buka uses his work to take a second look at himself and his home. The Johannesburg local has examined everything from gentrification to gender, always trying to inhabit a different point of view. His 2015 photo book Crossing Strangers began as an experiment in seeing his hometown in a disparate way. Photographing familiar streets, he asked himself what others see and what they miss. He bypassed areas that clog the news, to capture the spaces people forget.

Working with fellow creative Tumisang on Femme — a series examining the shifting identities of African women — he takes the same approach to his own gender and privilege. Revisiting his domestic creative landscape with a female counterpart, Buka acknowledges the challenges she faces that he never needs to consider.

Your recent book Crossing Strangers was very much about your hometown Johannesburg. How does the city influence you and your work?

The energy of Johannesburg forces you to get up and go hustle. Hustle can mean whatever, depending on your profession or your goal. For me particularly, when it comes to photography, I’m driven and inspired by the city. The energy is a positive one. The youth are at the forefront of wanting to change the stuff they’re not happy with and create best Johannesburg they can. I like working in the midst of that kind of liveliness and power.

What does the title mean?

The “strangers” in the title are both people and places. Sometimes I had encountered them before, but through the process of taking the pictures, I experienced them differently. I would see places and people at different times of day, in different moods, in different weather, and this would change how I saw them. They became “strange” to me once again.

Did looking at Johannesburg with the intention of making this book change how you saw it?

To be honest, creating a book was absolutely not the intention when I started out. I think partly that taking pictures of Orange Farm started because of how I saw the place. When you hear about the townships around Johannesburg, mainly it’s Soweto and Alexandra that are referenced. There is very little documentation of Orange Farm. It felt strange and sad to think that I wouldn’t have a record of it, so I started the documentation myself.

Through that process I started to notice new things about this place that I had lived in for years, but myself had overlooked. I had always found my surroundings intriguing and under-investigated. I wanted to try to understand visually, ‘What is this?’ questioning my own feelings when I looked around me. Taking the photos didn’t abate my curiosity about my home, but stirred it.

You mention that Johannesburg is full of contradictions. What do you mean by that?

Although I don’t show gentrification in the images, it underscored everything in the city. The spaces that I photographed in 2014 and 2015, some of them look completely different now — which tells you how rapidly the city is changing.

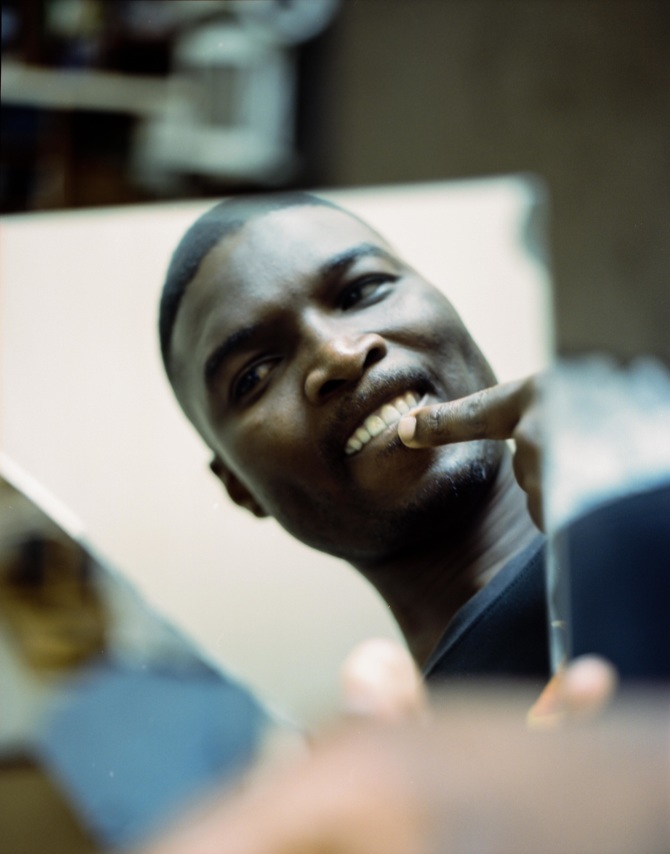

It seems like a lot of your work explores identity. I was interested in your series Femme looking at sexuality and African women. What were the Western depictions of sensuality you were trying to challenge?

The Femme project was a collaboration; I was approached by a friend and fellow creative, Tumisang. She was frustrated by the depiction of African women, not only in Western magazines, but also those that we receive locally. She wanted a vulnerable and honest depiction of herself in this state as a representation of women like her, and it was my job to facilitate. Tumi directed, designed, and wrote the project, also choosing the final shots. Before doing anything else, before picking up the camera, I just needed to listen, which I think was an important revelation.

This is obviously a very female-centric issue. How do you feel your gender impacted the project?

I think as a man it is important to check oneself often. I question myself frequently, ‘How do I unlearn everything that I have been taught as a man?’ I’m often not sure what the right thing to do is, and I think I am still figuring that out. I am aware of the fact that I am privileged to navigate Johannesburg with the freedom that my female counterparts don’t have, which from a practical perspective facilitated this project.

One’s experience of gender informs everything one does, and it can be difficult to unravel those threads. I think that when it comes to photography, listening to the experiences of women in the industry is hugely important. Sometimes the kind of degradation they go through is overt, like on street shoots where there are male passer bys touching themselves in front of the models. Sometimes it’s subtle — the way that a woman on set is spoken to by a male colleague. I’m still learning to be aware of my gender and to notice how it impacts my work, but I hope that I can keep learning and being vigilant.

These tend to be subjects unpacked by other women. Why did you want to look into it?

The Femme project landed in my lap, so to speak. It was borne out of a prior friendship and personal relationship. It seemed interesting because it was something that I wasn’t considering.

I think that it’s not only women who need to work on this subject. As men we actually need to engage and participate, no matter how uncomfortable or difficult those conversations are. It helps us understand what our counterparts are going through, what challenges they are experiencing. The more we engage, the more we talk about these topics — and even more importantly, listen — the better we understand what the next person might be going through.

What are the ongoing questions you set out to address?

Identity, identity, identity. I can’t stress that enough. There is a lot I want to explore — my family lineage, my past, current situations I’m faced with, being a Black man in this part of history.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

Photography Andile Buka