Since his first book It’s All Good was published in 2006, Boogie has been granting his audience rare access to a world defined by violence, poverty and disarray. Rarely romanticising the origin of intent behind his work, Boogie’s intimate images often offer a vivid portrait of metropolitan cities around the world. From Brooklyn to Belgrade – where he was born and is currently based – Boogie is a dedicated documentarian of street culture. His sixth photobook A Wha Do Dem due in late September was shot in Kingston, Jamaica and continues to curiously delve deep into a world familiar to few.

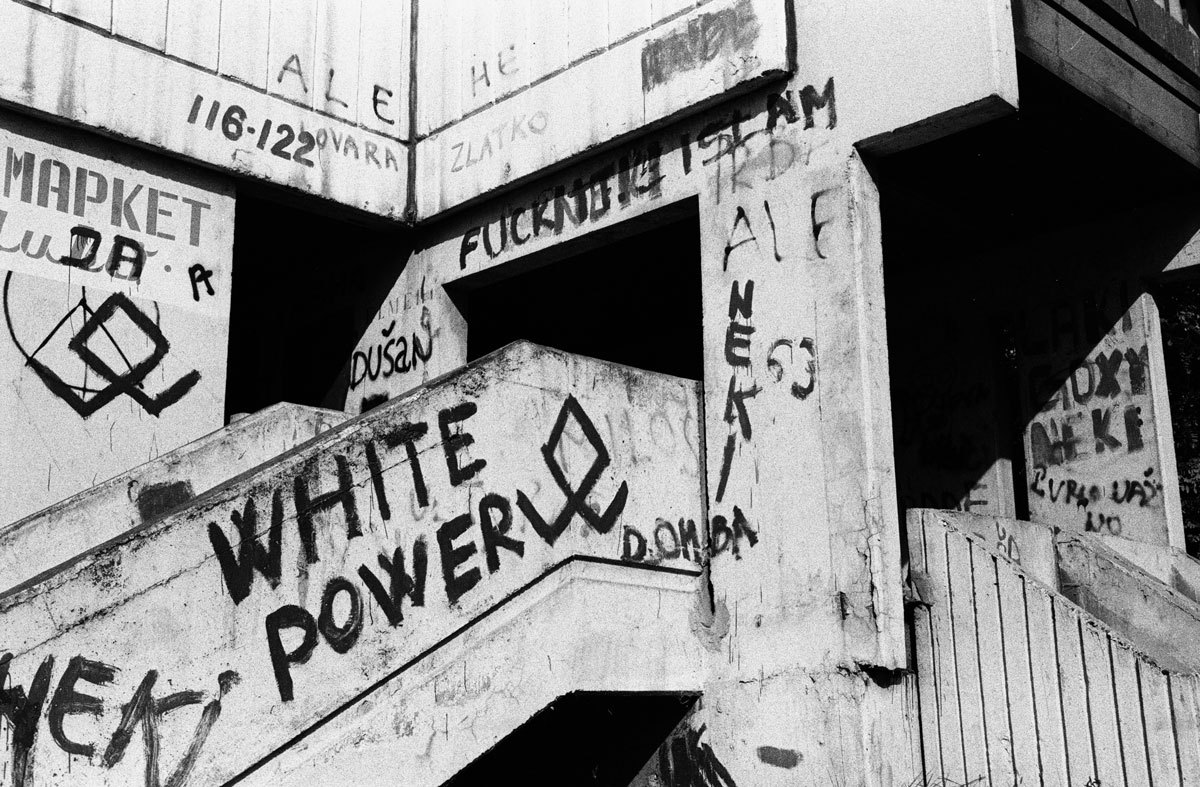

What do you remember most about growing up in Belgrade?

Belgrade made me who I am and influenced my style immensely. I had an amazing childhood: playing outside all the time, no fear, crime rates were low. It was a one-of-a-kind socialist country. Then in 1989, tensions started rising and I did military service. I remember coming back to Belgrade through Croatia and being kind of afraid to speak with a Serbian accent. We weren’t welcome there. A year or so later, the full-blown war started.

Over the years, a consistent theme has developed in your work. What is your main curiosity about street culture and how has it deepened since your first book?

I’m from the streets. Whenever I go to a new city, I want to experience what real people eat and what real people do. It also becomes really addictive, like being in a movie – you experience a reality that not many people have access to. For this past project, I had the opportunity to hang out with the cops and the gangsters. I think it’s important to meet and document both sides in order to really understand it from all angles.

Do you feel like you have to be particularly mindful of exploitation when documenting your subjects?

I don’t really think about it. Photographers who say “I’m trying to make a difference, or trying to change this or that…” We are just photographers. I think the reasons are pretty much selfish, we do it because we like to do it, it’s not about changing the world. I think that’s just bullshit. People try to make it sound so romantic and I’m like, ‘You’re not curing AIDS or fighting a war or saving anyone. You’re just taking pictures.’

How do you feel after, when you’re going through the images you’ve shot?

When you’re behind the camera, it’s almost like you don’t participate, you’re just an observer. After I would get so depressed; it was really hard to process. It doesn’t really hit you right away. I’ve seen people shooting up and smoking crack several times. After the first book, it became hard for me to see ‘normal’ shots around me. It was hard to be inspired by something that wasn’t a gun or a needle or something like that.

Becoming a fly on the wall and gaining the trust of your subjects seems like a job in itself. What’s your approach?

People feel each other’s energy before words are spoken, especially people who are on the edge of society – I think they follow and trust their instincts more than we do. They can tell if you’re real or not. I’ve always had a good relationship with people in the margins of society. If you give respect, you get it back. I’m not fearless at all because I care about what happens to me; I don’t think any image is worth dying for. In the streets, your instincts are your best tool. When my instincts tell me it’s gonna get nasty and I need to go, I go.

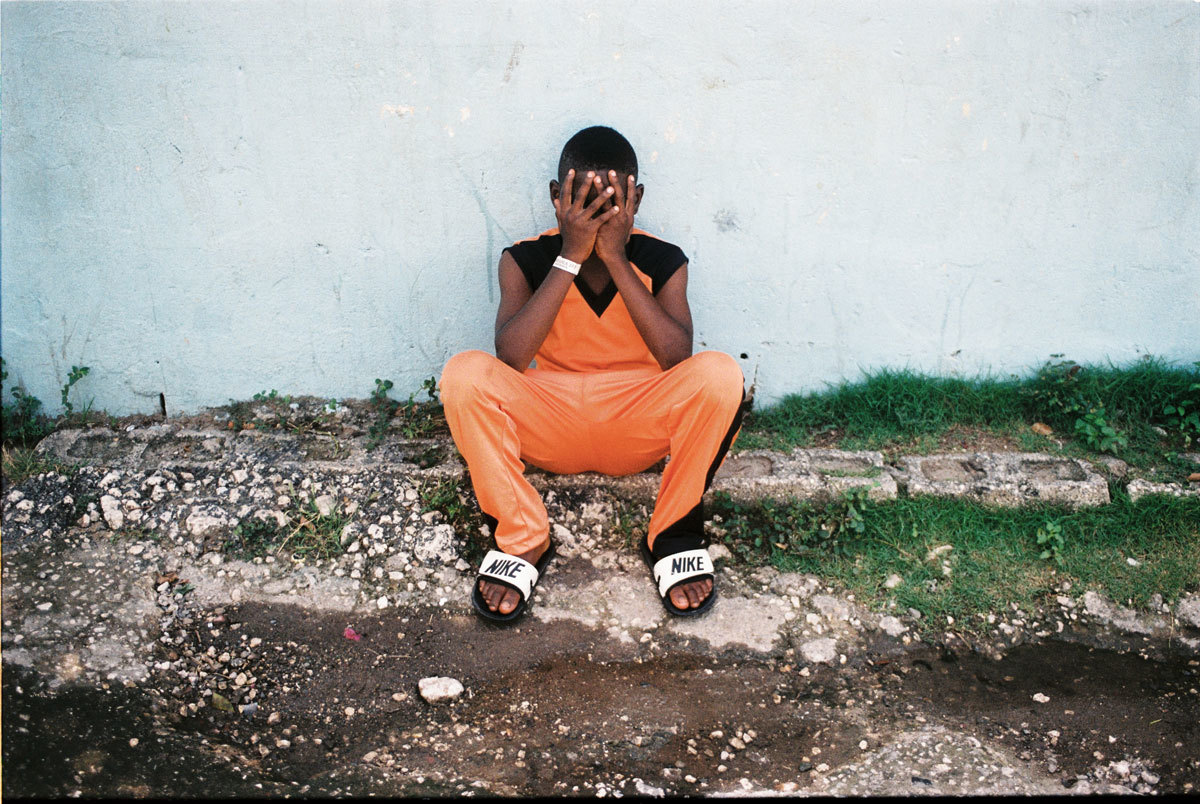

A Wha Do Dem is the title of your new book shot in Kingston, Jamaica. How did it develop?

On the last night of my vacation in Kingston with my wife, I took some pictures of some guys with machine guns who I was introduced to by a friend of a friend. Once the connection had been made, it was up to me to gain their trust, stay there and build something. I flew back to New York and couldn’t stop thinking about it. After two months, I went again. Jamaica is much more intense than anywhere I’ve been. In my other projects, the surface was quiet and normal–you have to seek what you’re looking for. Kingston was crazy, everything was much louder and in your face.

This will be your first publication in color. Jamaica was a great place to explore that…

I felt like it would be really tragic for me to shoot Jamaica in black and white; it was the perfect place to explore a project in color, which I’ve been using more of over the past four years. I was obsessed with the washed out, painted signs there, it’s a big step for me.

What are you excited about working on next?

The DEMONS project I’m working on: wet plate collodion on black plexiglass. It’s the closet thing to art that I’ve done, everything from the process to the final piece. There’s no duplicating of these images – that technique creates something beyond this world. The older, I get the more inspired I become. Maybe in the beginning I was after extreme situations, now I’m not. You don’t need to go to a war zone to find good shots, they’re everywhere. You don’t want to keep shooting the same shit over and over again. If you change as a human being, your work will also.

Credits

Text Zeyna Sy

Photography Boogie