Daniel Jack Lyons: From rising stars to industry heavyweights, i-D meets the photographers offering unique perspectives on the world around them.

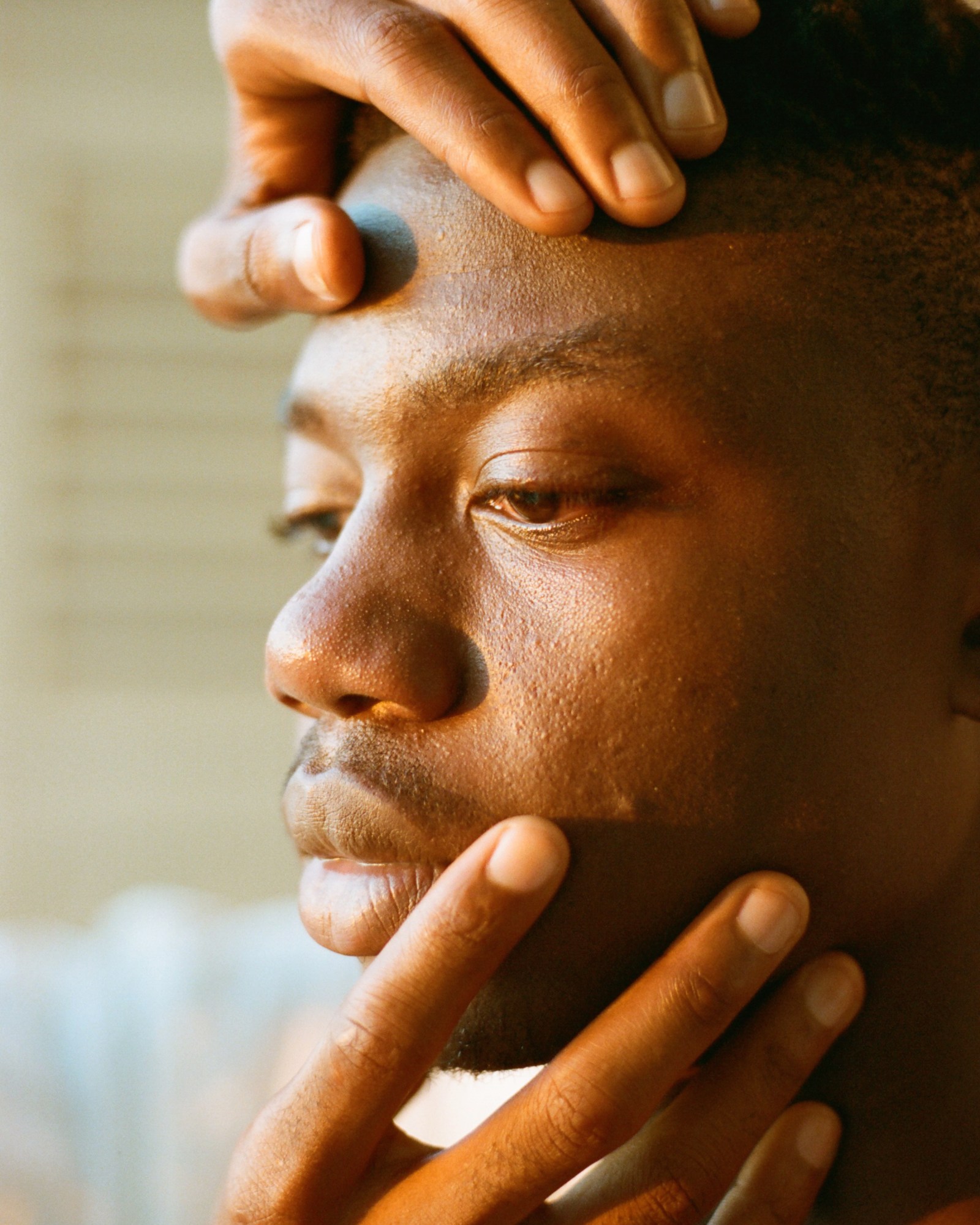

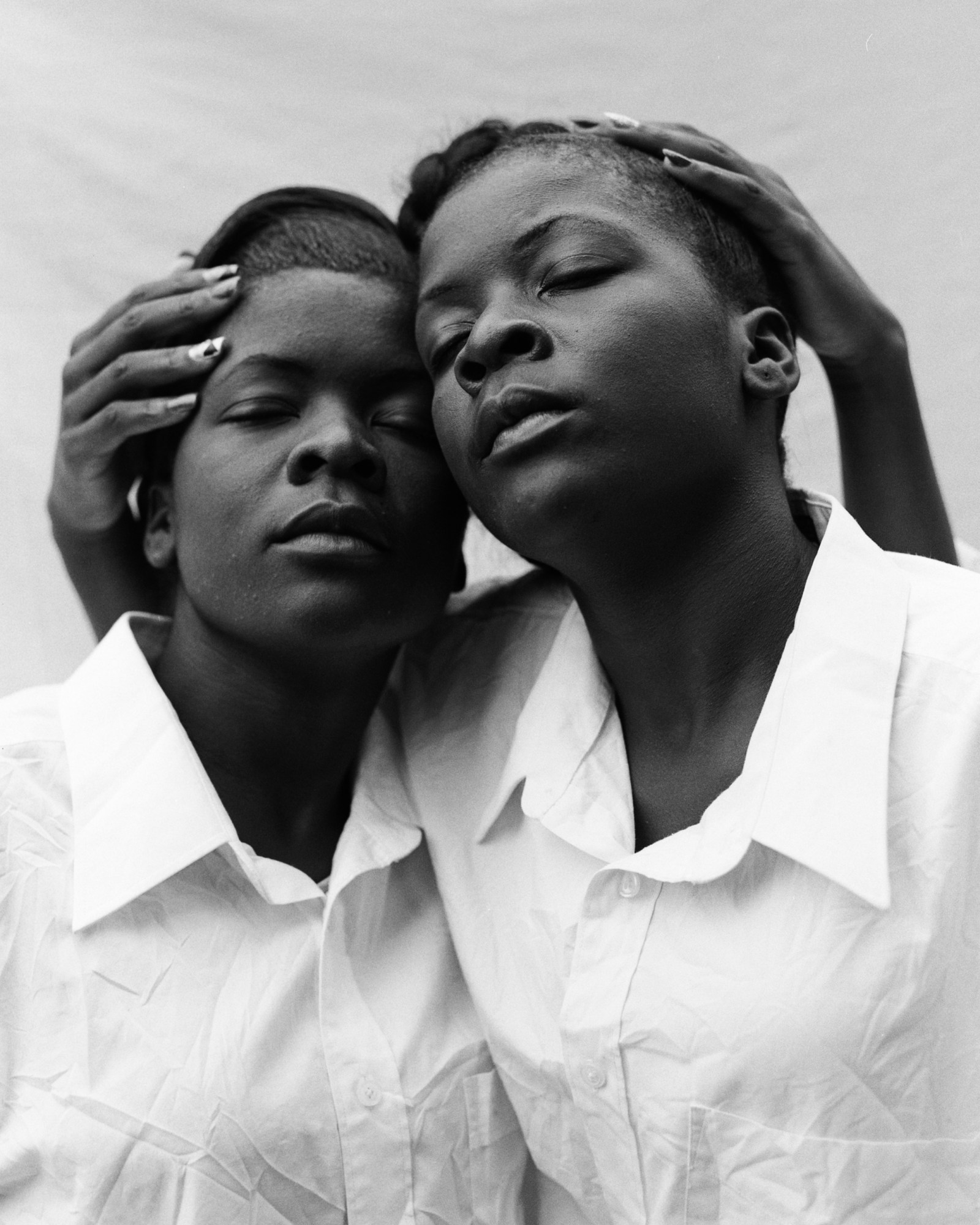

Photographer Daniel Jack Lyons uses his camera to find moments of equanimity in often fraught situations. From his portraits of Mozambique’s vilified LGBT+ community to his images of displaced Ukranian youth throughout the Russian military occupation, Daniel’s work confronts you with the reality of a situation without undermining its subjects or the story behind it; always framed powerfully — an individual against a backdrop of persecution.

Raised on surfing, skating and punk rock in a typical southern California beach town, Daniel’s been taking photos since his early teens. “I played in a couple of terrible punk bands, and photography was a natural way for me to document my friends, he says. “It was also an excuse to spend long periods of time in the dark room, which at that age was like a sanctuary to me.”

On leaving school, Daniel began studying photography and sculpture at university on an arts scholarship, but coming out as gay midway through his course, his interests began veering towards social and critical history instead. “I changed my major to social and behavioural sciences and lost the scholarship. But photography continued to play an integral role in my life even though, from then on, it remained outside of my studies.” His work has since navigated the intersection of these two ideas.

You’re also a qualitative researcher and photographer. Can you talk a bit about how you bring these two practises together in your work and what you set out to achieve?

I have a masters in Medical Anthropology and consult with human rights agencies to design qualitative research programs, which in many ways informs my photographic practice more than anything else. The participatory and ethnographic nature of the projects that I have worked on have shaped the way I approach photography as a collaborative endeavour. I spend a good amount of time with people before taking out my camera. That said, the individuals and subject matter that I choose to photograph are usually kept separate from my work as a human rights consultant.

I always hope to capture a feeling that is authentic to the individual in the photo, a sincere moment or an intimate exchange. I’m very present when shooting, and for that reason my relationship with the participant is extremely important.

The LGBTQ community in Mozambique has been a particular focus of yours and your project Hotel Luso shows a real connection to its subjects. How did you come to know the communities you shot?

I lived in Mozambique for four years, from 2005-2009. And since then, I have gone back frequently for work and personal projects. In the last five years I have averaged more than a quarter of my year there. Over the last decade I have formed friendships with people who are like family to me, many of whom are part of the LGBT community. For several years there were frequent discussions among friends about creating a project that would increase the visibility of LGBT Mozambicans. Currently there are no public spaces for queer people in Mozambique — no gay bars, no pride events. Hotel Luso became a symbol of that isolation, and an opportunity to reclaim, and queerify a space, if only for fleeting moments. That series was a collective effort from everyone involved, and was ultimately an opportunity to collaborate with friends on a project aimed at decreasing stigma in Mozambique.

How do you define appropriate boundaries in these very sensitive environments when you are ultimately a passing visitor in a delicate situation?

I treat each project as a collaboration with the individuals and communities that I am working with. In that sense, my participants define those boundaries for me. I just returned from Brazil where I have been shooting a series on indigenous youth culture in the Amazon. Everyone I photographed in the series either approached me, invited me to their home or played a role in deciding how and where they wanted to be photographed. Speaking Portuguese definitely helped in that context — a lot of time was spent hanging out before even loading film into my camera.

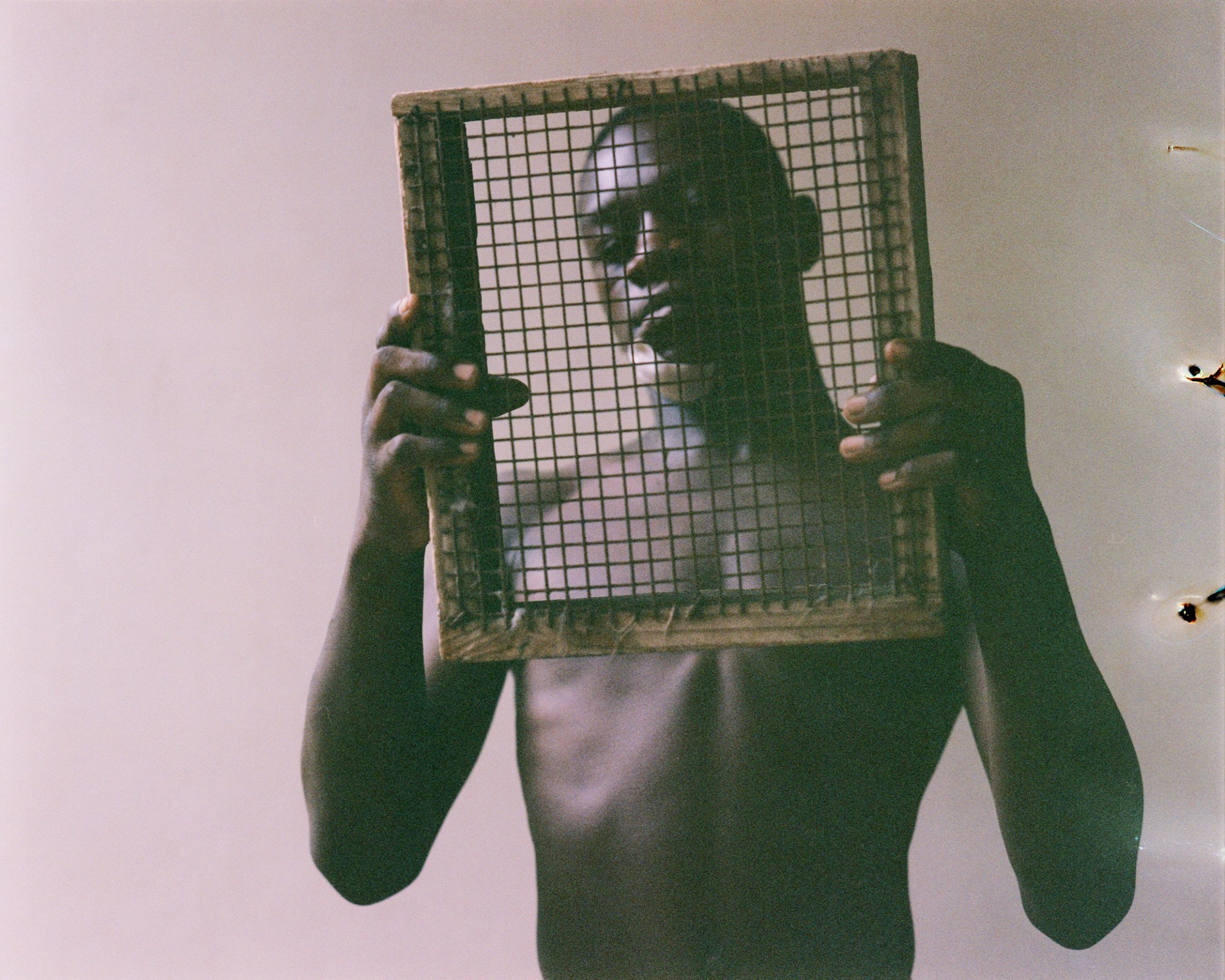

Similarly with MAHOTAS — shot in a psychiatric ward in a Mozambique hospital — how did you develop relationships with the subjects? Each subject masks their face with an item of significance to them. Was the symbolic item a way of diffusing some of the tension and creating a more natural dynamic?

My work with MAHOTAS began as a photography workshop that I taught in a psychiatric clinic for both staff and residents. As I got to know the residents, I expressed an interest in creating a series of portraits with them. Together we discussed what that might look like, and what they were interested in conveying. Each resident in the clinic has a job, a form of occupational therapy that ranges from animal husbandry to artisanal crafting. The residents were proud of their work, and wanted to display that. At the same time, I had some ethical reservations due to many of the resident’s cognitive disabilities, which made it questionable whether they really understood what it would mean to have a photo of them published or exhibited. And since mental health is highly stigmatised in Mozambique, I wanted to be extra cautious of compromising them in any way. So we came up with the idea that each resident would bring an item that symbolised their work in the clinic, and I used that item to obscure their identity in the photo, as a way of protecting them.

With Displaced Youth — shot in Ukraine during the Russian military invasion — what did you want to convey about the situation your subjects were in through your images?

It came about from a combination of working in displacement camps in eastern Ukraine, and making friends in Kyiv, all of whom were artists or musicians and all of whom had their own stories of displacement. At that time, most of the photographs documenting displacement there and in Crimea focused on the aftermath of violence. But the desires and dreams of my Ukrainian friends were not so different from those of friends at home. I wanted to create a series to remind us that any country can, at once, be a site of conflict and also a place where young people have few obligations or cares beyond the yearnings of being young. I wanted people outside of Ukraine to relate to the photos, and take an interest in their stories, not because of a noticeable difference, but rather due to a sense of similarity.

How do you strike a balance between showing the stark reality of your subjects whilst retaining their power and not framing them as vulnerable?

I am perpetually inspired by people’s resilience in the face of harrowing obstacles. I think everyone, no matter the country or culture, has a story of struggle that they have overcome in some way. I always try to shoot from a perspective that celebrates that vitality in a positive light.

Do you remember the first time a photographer’s work had a profound effect upon you?

I remember the first time I saw the work of Nan Goldin — it blew me away. I couldn’t get those photos out of my head! And I’m sure, on some level, it had an effect on my approach to documentary work.

How do you balance creativity and commerciality?

By critically questioning the ethical integrity of each project, regardless of how commercial or non-commercial it is.

What makes a compelling, emotive photo?

I’m not sure I can say! Compelling and emotive photos are like magic to me — trying to define it can be a bit of a mystery, but I always know it when I see it.

Credits

Photography Daniel Jack Lyons