How do you write about punk and avoid the cliches? What testament will do justice to the energy of the music, the spit-flecked rage, the nihilistic destroy everything impetus? Is it possible for those of us who weren’t there to understand the apocalyptic, comet-like impact it had on youth culture? Punk destroyed everything and then rebuilt everything.

Punk’s position then: a reaction to the state of the world as it was in the late 70s as society felt on the verge collapse, a society with Thatcher lurking around the corner. Punk’s position now? A spirit that still lives on? As necessary as ever? Or is punk now a museum piece, stuck in aspic, irrelevant? That’s the dilemma punk finds itself in, 40 years on, as controversial as ever. This is the landscape that Derek Ridgers’ new book, Punk London 1977, drops into.

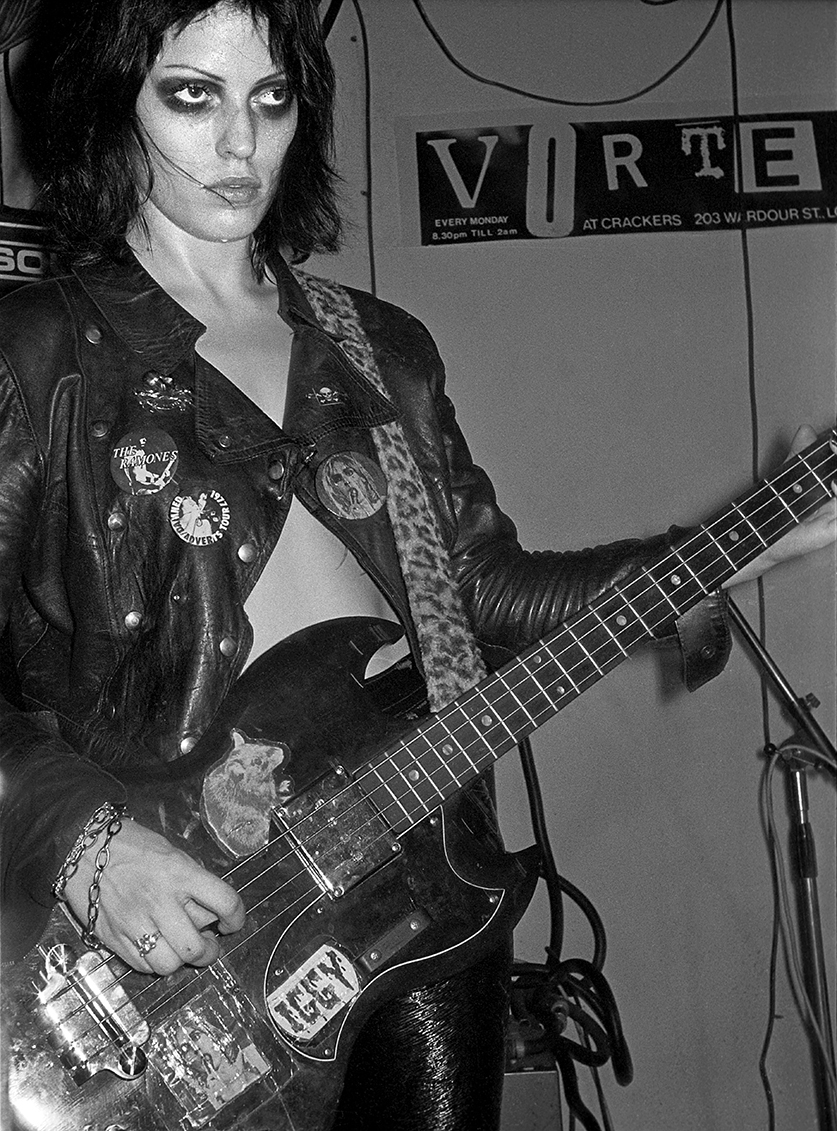

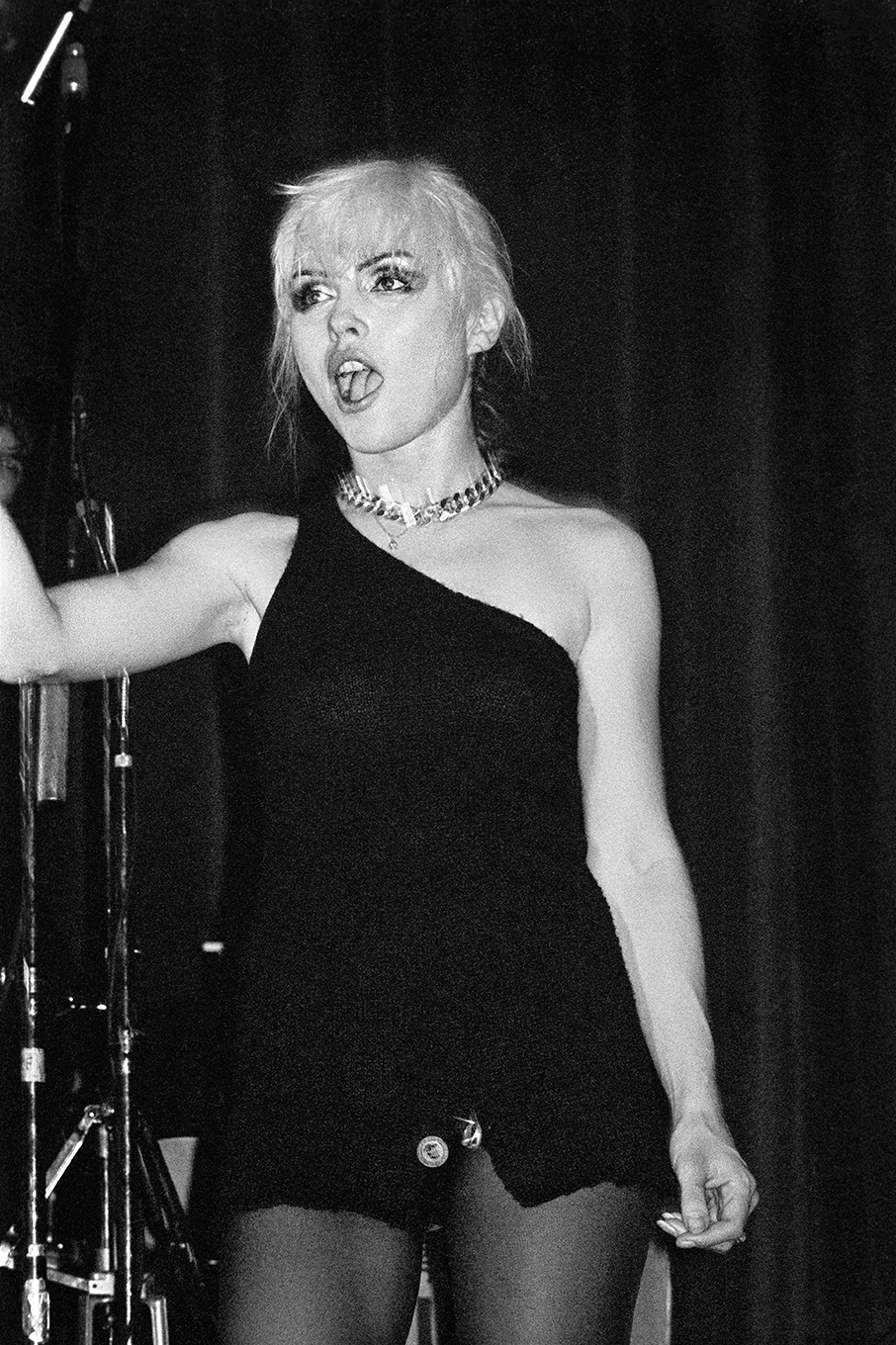

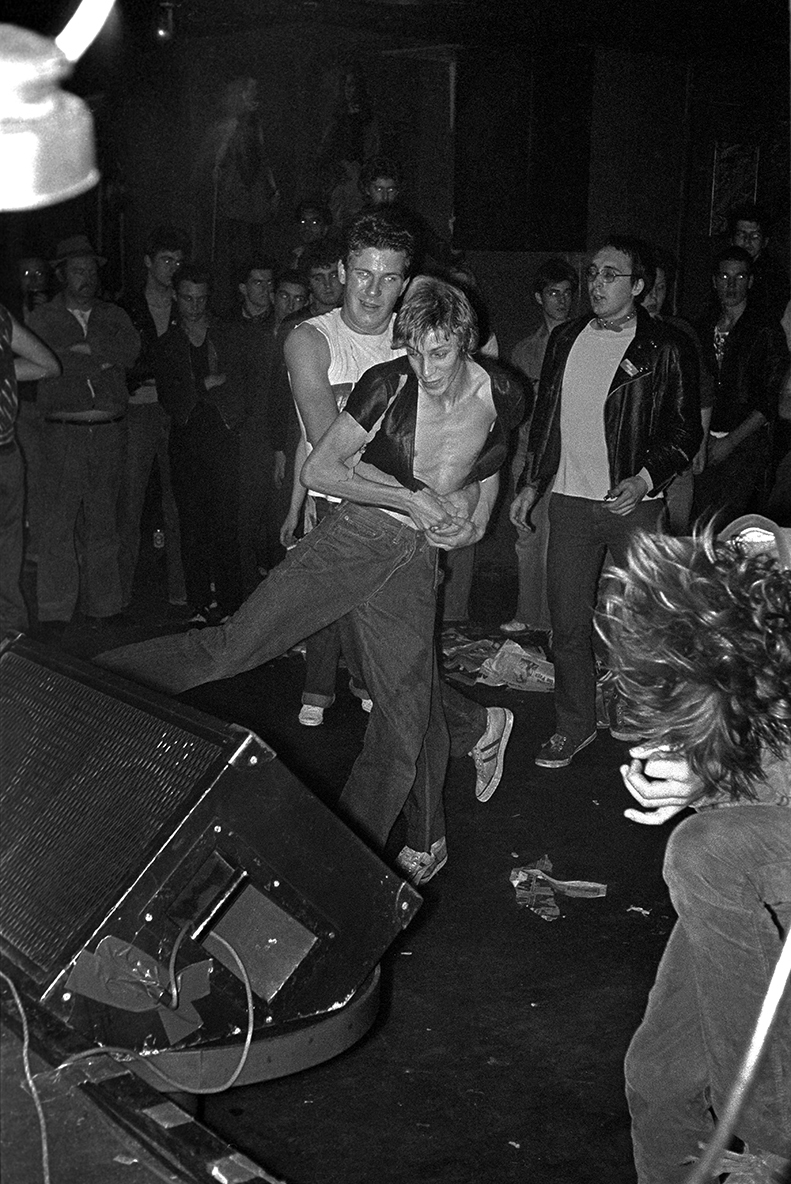

Ridgers’ photographs stand as an incontestable monument to the vitality, originality, and spirit of London’s iconoclastic subcultures, safety pins, swastikas and bondage gear. He captured the explosion of fashion that followed the punk big bang of 1977; he shot skinheads and New Romantics, mods and rockers, street kids and club stars — immortalizing and defining youth culture, imbuing it with timeless gravity.

Punk changed everything, even Derek himself. In 1977 he was a cardigan-wearing art director at a West End ad agency and part-time photographer, a generation older than the iconoclastic kids who made punk happen. He travelled down to the opening of the Roxy and fell into documenting the cultural explosion underway at the venue.

Between the official opening on New Year’s Day 77 and its closure in April 78, the Covent Garden venue played host to just about everyone: The Clash, Sex Pistols, The Buzzcocks, The Damned, Wire, Siouxie Sioux. Ridgers was there, turning his camera on the audience, documenting their new vision of contemporary culture, before it turned into stereotypes.

To celebrate punk’s 40th birthday, Derek has, for the first time since 1978, opened up his archive of images shot at the Roxy and Vortex, to coincide with the Punk London anniversary. We sat down with the iconic photographer to talk about punk then, punk now, and Joe Corre’s bonfire of the punk vanities.

Are you bored of talking about punk yet?

No, not at all. I haven’t spoken about punk much and the truth is, although I was there, I was a complete outsider. Getty has a photograph of me at the Roxy; I was dressed as I would have been at my office job — in that hot, loud, sweaty, heaving punk club I’m wearing a v-neck cardigan. My whole life has been from the perspective of someone who wears a v-neck cardigan in inappropriate places. Often intentionally.

Do you think we place too much emotional attachment to the moment punk was created?

Well, a certain generation does. It was a defining cultural moment for a generation, a real seismic shift artistically. It didn’t have the same effect with the cool kids of my generation because we had the Summer of Love and we can remember when bands like Pink Floyd and Jefferson Airplane were cutting edge — all the stuff that punk was supposed to be against.

Is it possible for those who didn’t go through it to comprehend punk’s impact on pop culture?

Most probably not, but then why should they? Every generation has their own obsessions and moral panics.

Do the images instantly transport you back to the time?

No, not really, to be honest. I think I was too old by then for photographs of that time to have that effect. Besides, I’ve been living with these images for 40 years now; these images have become my everyday reality.

Did punk change you?

Immediately before and during punk I was working as an art director in a West End ad agency. I carried on afterwards for a bit, too, but the early success of my photographs — they were shown at the ICA in 1978 — gave me the first glimmer of an idea that I could actually give up being an art director and become a professional photographer. Punk gave me opportunities both socially and vocationally to make some big changes in my life. It still took me a few years to achieve, but the seeds were sown by punk.

In 1977 I had a young family and we lived on a shabby council estate. My family was being subjected to quite a lot of harassment by some of the local kids. I thought of a slightly devious way to stop it. I got to know and befriend a couple of the lads the younger ones looked up to. Basically nice kids but both a little yobbish. And just slightly older than the ones who were causing my family problems.

I didn’t ask for their help though, I just got friendly with them. I gave them some punk t-shirts and got their names onto the guest list for a gig in Uxbridge by the band Penetration. A gang of skinheads turned up, attacked the band and there was a mini riot. I was right in the middle of it and nearly got my legs broken. The lads I’d taken to the gig were really quite scared.

After that, my new friends didn’t want to go to any more punk gigs. But for some reason the harassment stopped overnight.

Who was the most important band, for you, to come out of the punk scene?

That’s an easy one. The Sex Pistols. Without them, would any of it ever have happened? I doubt it. And musically, the Clash in 1977 were one of the greatest live bands I’ve ever seen. As a live act, they went rapidly downhill after 1977 but when they were great; there has never been a band that had such a ferocious commitment on stage.

Why do you think punk was so shocking in 1977?

It was shocking because it was supposed to be. Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s designs for their Seditionaries shop intentionally used shocking images to outrage middle England. And they succeeded.

Did it feel political?

Not really because, after all is said and done, this is about clothing and pop music isn’t it? But it certainly wound up a few politicians. Most notably the London Councillor Bernard Brook Partridge, who was quoted as saying “The Sex Pistols would be vastly improved by sudden death. I would like to see someone dig a huge hole and bury the lot of them in it.” Whatever happened to him, eh?

What’s your opinion on Joe Corre burning his collection of punk memorabilia?

I’m bemused but aside from that, I’m not sure my position really entitles me to have an opinion about this, does it? At the time I was on the stood on the sidelines, simply watching and my perspective remains essentially the same. Punk meant something once, in the context of the time, but other than historically, it doesn’t really mean the same thing now. So I would say this to Joe Corre: punk is alive and well but it isn’t your punk any more. It belongs to the world now.

Does punk still have a place in contemporary culture?

In the UK — aside from the revivalist bands that come along from time to time to play loud, quick, three-chord punk music — it’s really just a fashion thing now. And, in all honesty, why shouldn’t it be?

In the rest of the world, it’s seen totally differently. It’s a lifestyle. You get Japanese punks and Los Punks in East LA. It’s global thing now. Some of them, maybe even most of them, won’t have a clue about Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. Many of them have mohicans — which no one ever had in 76/77 — and that’s fine too. Wasn’t one of the original punk principles that there were no rules? A lot of people get on their high horse and say “this is punk” and “this isn’t punk” but everything evolves.

If punk means something to young kids these days and it gives them enough focus to get up off their arses and do something, who really cares if it adheres to a set of somewhat nebulous principles largely forgotten before they were born?

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography Derek Ridgers