What will the future look like? Refer to many works of speculative fiction – from 1980s cyberpunk classics like William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner to later sci-fi epics like the Wachowskis’ Cloud Atlas (2012) – and it’s likely to be full of cities resembling Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. Roam through these steely, smog-covered cityscapes, and in the neon half-light, you’ll probably encounter robotic citizens devoid of emotion or feeling.

“When I first saw Blade Runner, I thought, that’s not the future, that’s really just Hong Kong,” Ramona Jingru Wang, a Cantonese photographer born and raised in Guangzhou, China, and now based in New York, tells me. “These films use Japanese kanji to make the setting look so dystopian, and that’s kind of how Western media looks at Asian bodies and Asian culture in general. You’re just like a kanji character to them. They use you to make these films look futuristic and dystopian instead of seeing you as a fully-formed individual.”

Present in science fiction and real-world news coverage, this phenomenon of imagining Asia and Asians in hyper-technological terms is known as techno-Orientalism. Akin to Edward Said’s foundational concept of Orientalism, it operates through a process of othering, figuring Asians as distant and enigmatic. However, these “others” are not portrayed as primitive or uncivilised. Instead, they are seen as technologically advanced – threateningly so – and in desperate need of Western heroes to inject them with consciousness, conscience, and humanity.

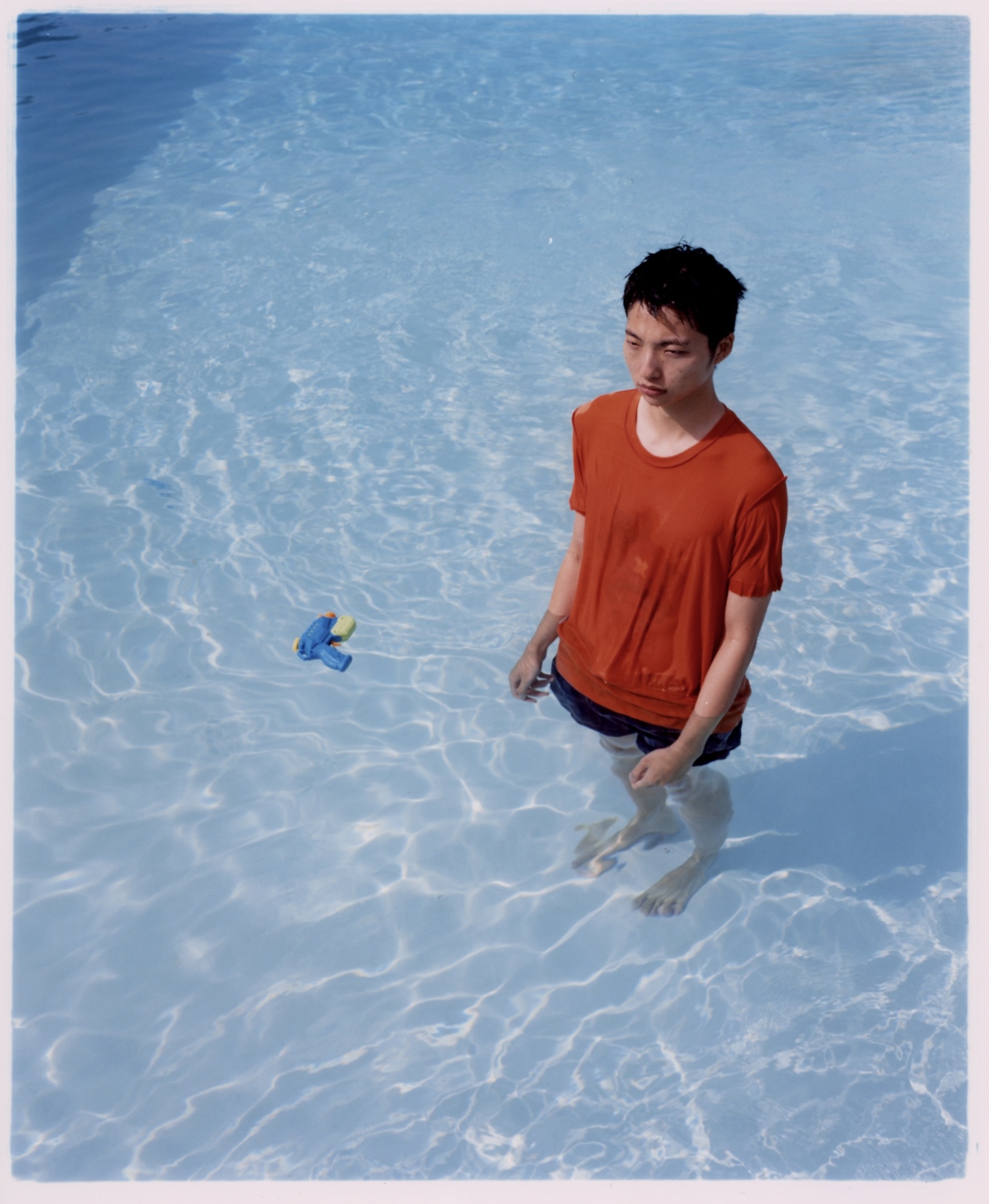

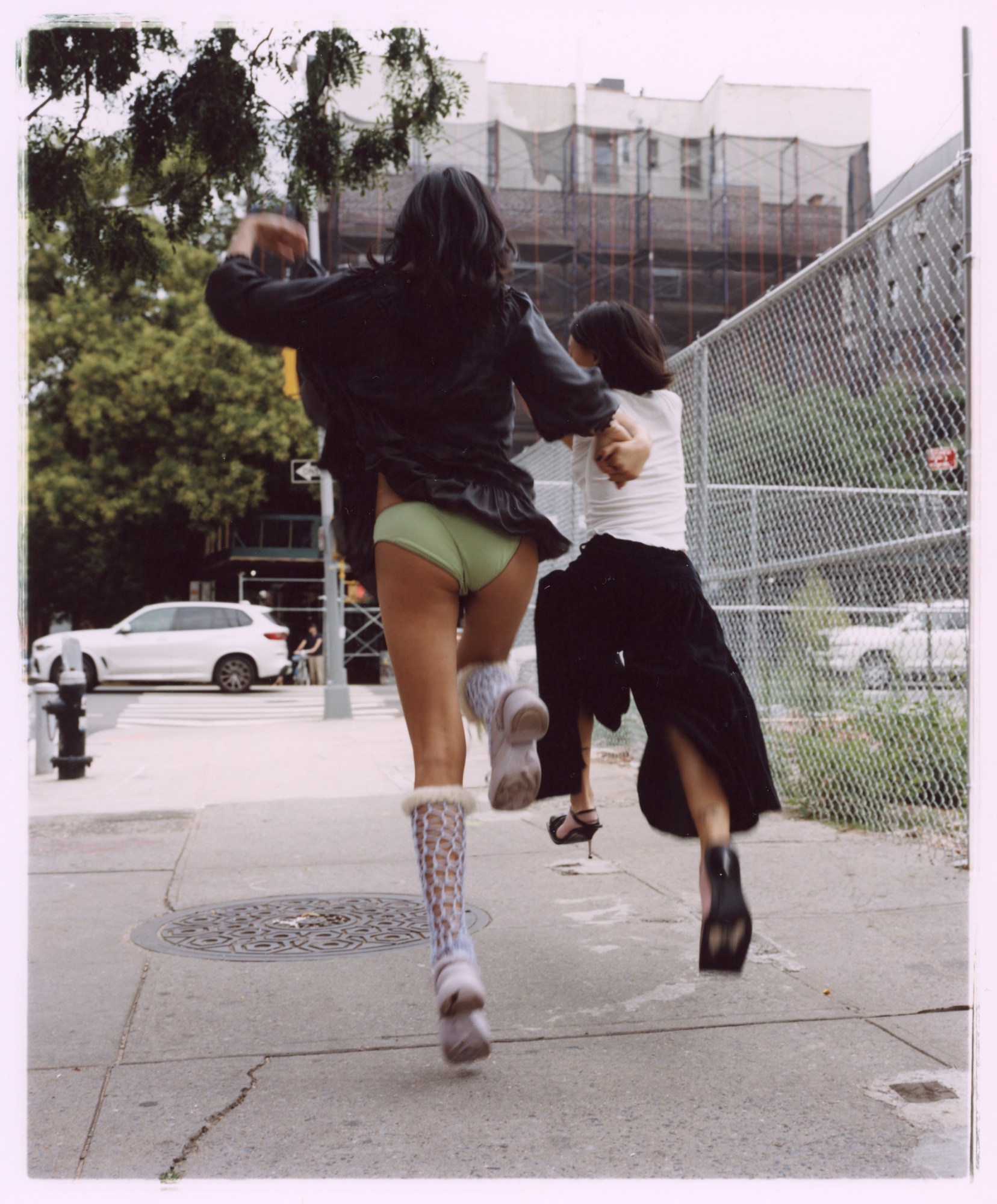

Ramona’s “mockumentary” photo series My friends are cyborgs, but that’s okay – a collection of portraits and staged scenes taken within her queer Asian community in New York – is an attempt to challenge these stereotypes of Asian identity in mainstream media. “These sci-fi films are full of sexualised, dehumanised Asian-looking cyborgs,” she says. “I wanted to take the figure of the cyborg, this thing that is part-organic, part-mechanic, and restage it to celebrate our hybridity.”

The 28-year-old artist began looking at her friends and noticing all the ways they stood out from the mainstream, all the ways they resisted stereotypes and rejected rigid boundaries and binaries. “Sometimes we stand out because of our racial identity, but it’s also often because of our personalities, our unique fashion sense, our unconventional lifestyles or creative work. I’m showing off our hybrid identities to create a narrative of cyborgs of our own.”

In critiquing techno-Orientalist narratives, Ramona was also inspired by Donna J. Haraway’s controversial work, A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century (1985). “We are all chimeras, theorised and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism – in short, cyborgs,” Haraway writes, and suggests that “women of colour” in particular “might be understood as a cyborg identity, a potent subjectivity synthesised from fusions of outsider identities”.

For Haraway, the idea of the cyborg challenges traditional boundaries between humans and machines, as well as the distinctions between genders and other social categories. She asks the reader to take “pleasure in the confusion of boundaries” and proposes that by embracing our cyborg nature, we might begin to break free from rigid societal norms and create new possibilities for identity and existence. “Haraway says that this kind of identity presents a new way of living. It’s transgressive yet progressive,” Ramona says. “I feel that’s true for my friends in this project. They are living new lives.”

In keeping with the theme of hybridity, Ramona’s images are partly staged and partly candid. When photographing her subjects, she travels to “wherever they feel the most connected and comfortable”, from bedrooms and bathrooms to gardens, parks, and pools, and asks them to imagine they’re a cyborg living in the real world: “What makes you most out of the ordinary? What contradictions and complexities do you contain?”

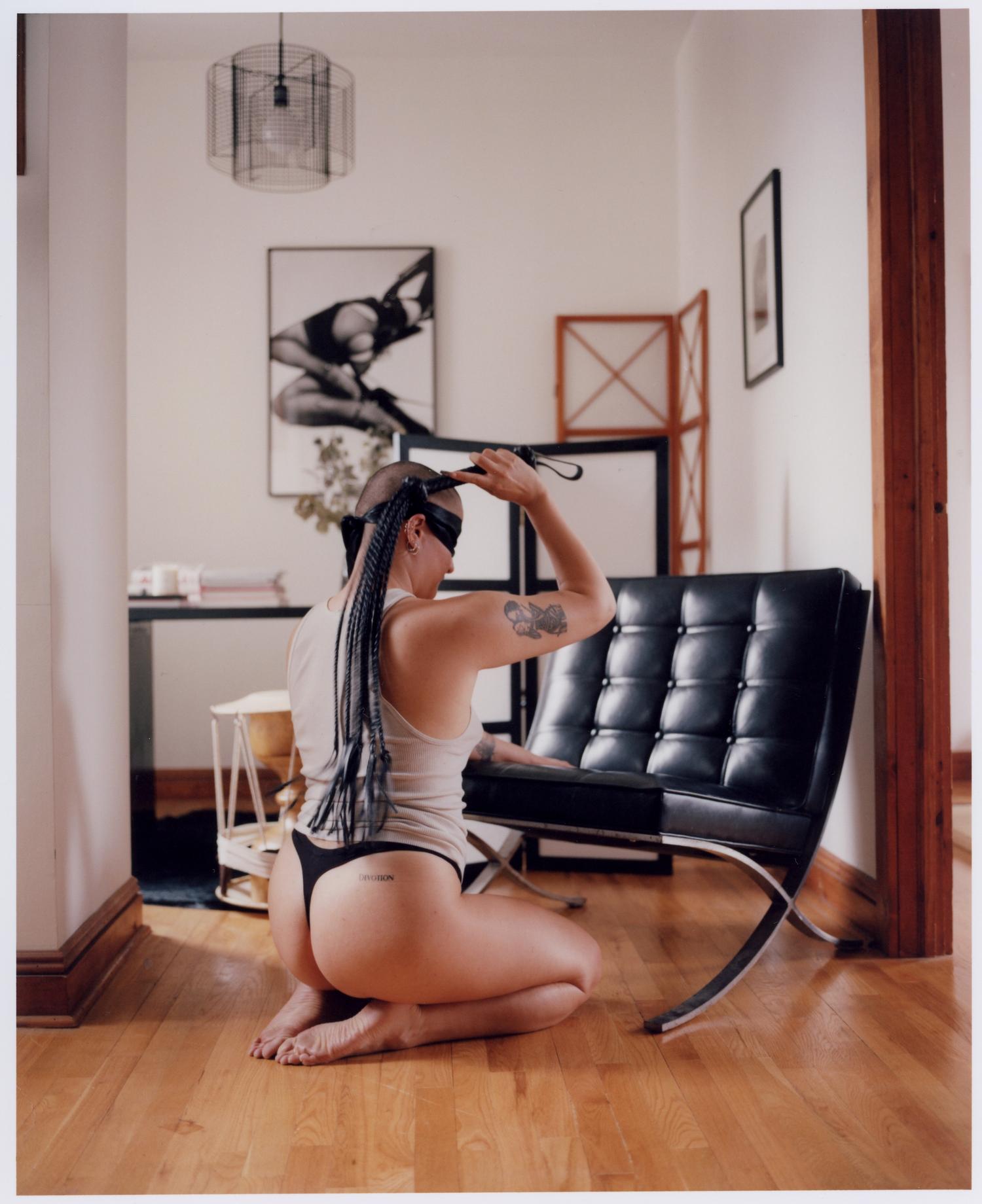

In one set of images, Ramona is invited into the home of Vanilla Honey, a queer Korean-American architectural designer active in New York’s BDSM scene who investigates the intersections of eroticism, subculture, and belonging. Ramona captures Vanilla Honey engaging in private rituals of self-inflicted pleasure and pain. “They really resonated with the project,” Ramona says. “They said they often feel out of place because they have so many desires that they want to express, but because of their Asian look, people don’t like to talk about it. They’re either super-sexualised or seen as not sexual at all.”

Here, Ramona brings up Alex Garland’s sci-fi thriller Ex Machina (2014), which pivots around subservient, fetishised ‘fembots’. The maidservant Kyoko, played by British-Japanese actress Sonoya Mizuno, is created to fulfil the needs of her master, be it domestic chores, sex, or dancing with him to Oliver Cheatham’s “Get Down Saturday Night”. Unable to speak English or express emotion, Kyoko is voiceless throughout. She is destroyed at the end, and not granted the same redemption as Alicia Vikander’s humanoid robot, Ava. “I was shocked watching this character. That film contributes to a long-lasting stereotype in real life of Asian women as sexualised but static,” Ramona says.

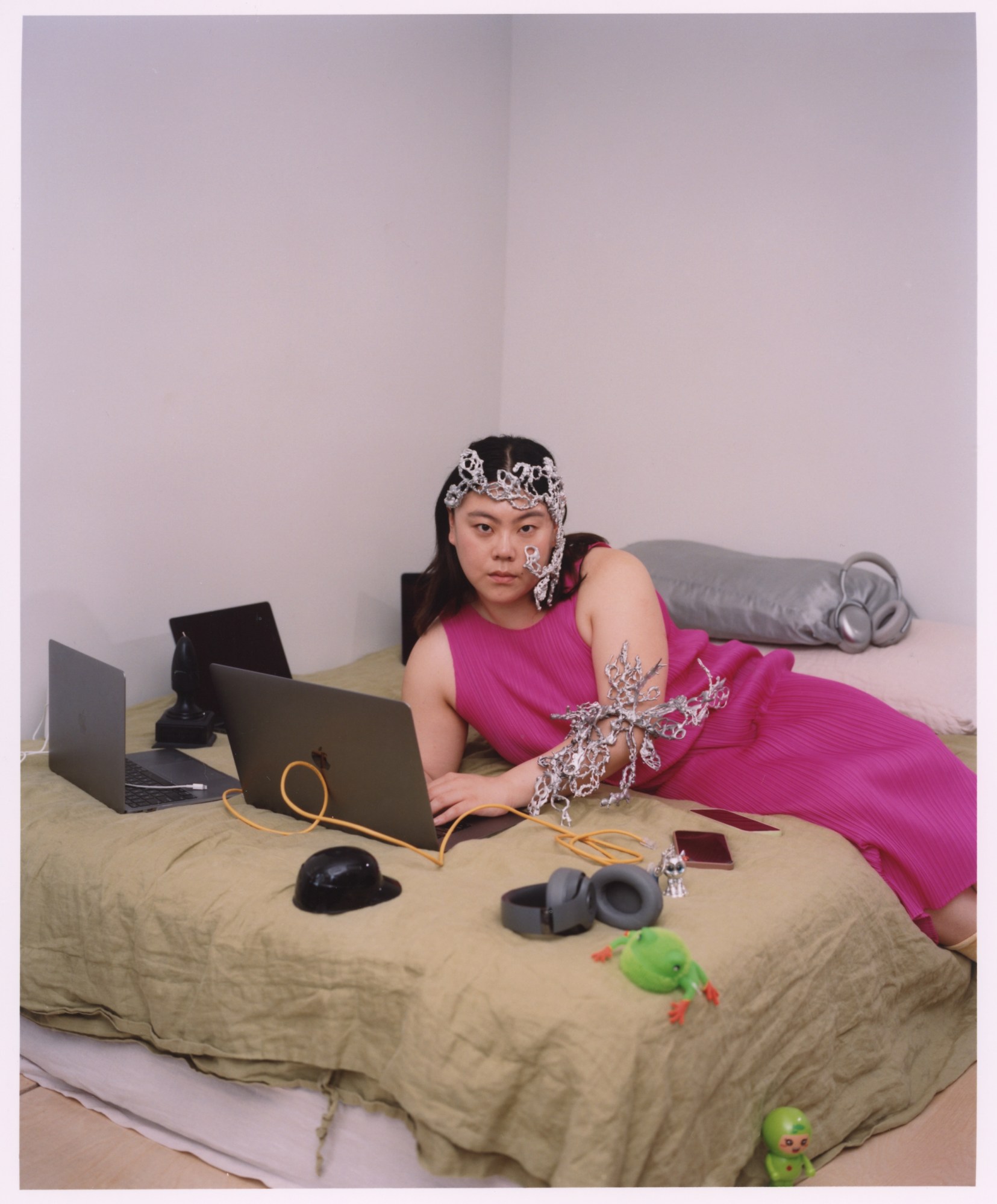

Another portrait depicts model and UX researcher Han Na Shin posing on her bed in body jewellery, surrounded by her many laptops. “By studying computer science and working at Google, Han Na sort of fits the Asian stereotype of being a model student and having a reputable job, but she’s also working as a plus-size model, which is very unconventional,” Ramona says. “She made me think of the cyborg identity in a really positive way.”

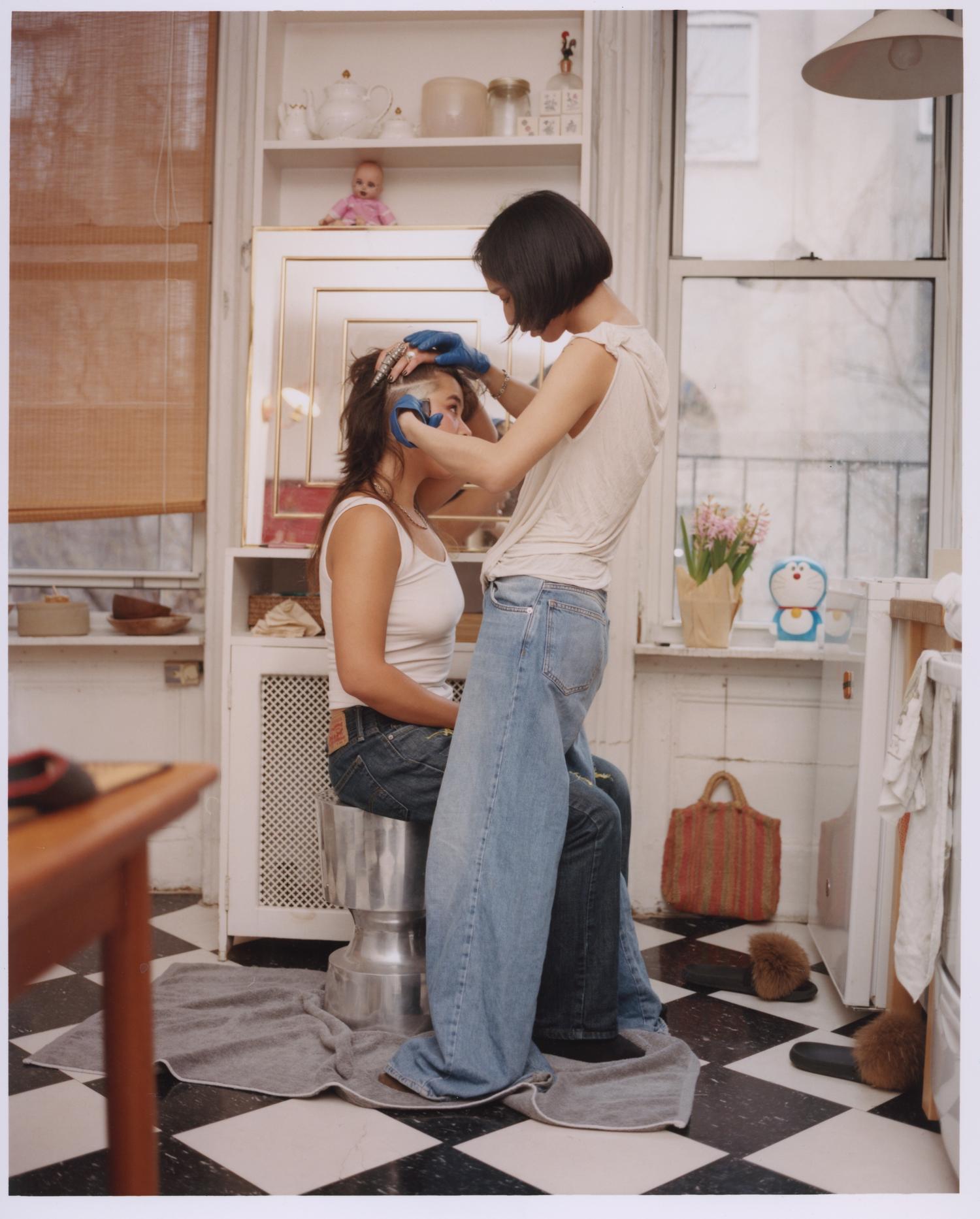

Tenderness ripples through Ramona’s images as she holds space for her subjects, whether in everyday moments of friends giving each other buzz cuts to avoid the expense of salon fees or sisters sitting around a kitchen sharing stories and photographs of their grandma’s career as a professional opera singer in China and the US. From reaching out to her friends and understanding their needs to hand-printing her film photos in the dark room, care is a vital aspect of Ramona’s image-making practice.

“For a long time, I only saw photography as an object that’s similar to other art forms, where you work on it yourself and present the end result to the viewer,” she says. “But when I started modelling after moving to New York six years ago, I realised that the process of making an image can have long-lasting effects on everyone involved. That’s when I began thinking about photography as an act of care.”

While studying for an MFA in photography at Pratt Institute, Ramona was struck by the work of theorist Ariella Azoulay, who calls for a more ethical engagement with image-making and proposes the idea of “the citizenry of photography”. Instead of being an object of art, Azoulay suggests, photography creates a form of citizenship or belonging for both the subjects depicted in the images and the viewers engaging with them. In Ramona’s words: “We need to care as much about the connections that are formed during the process of photographing as the final image.”

For Ramona, My friends are cyborgs, but that’s okay is fundamentally an act of connection. It’s her creation of “an imaginary community of cyborgs” to help others like her feel a sense of belonging, even as they stand out and celebrate their differences. In future, she’s committed to expanding the project outside the states and reframing Asian identity in a more global sense. In the meantime, she says, “I’m still waiting for a good sci-fi movie with Asian casting and an Asian setting that’s not super techno-Orientalist.”

Credits

All images courtesy Ramona Jingru Wang