“When I started in the late 90s, there was this sense that history was over,” explains Tobias Zielony, one of Germany’s foremost documentary photographers. The impression was shared by many across the Western world: as the Cold War thawed and the existential struggle between capitalism and communism had supposedly been settled in the former’s favor, there was a naïve sense — theorized and problematized most notably by Francis Fukayama, author of The End of History and The Last Man — that the ideological conflicts of the bloodiest century in human history had been resolved. Of course, Zielony immediately interjects, peace didn’t last: “When September 11 happened, all of a sudden, the world exploded.” History’s engines roared back to life, and Zielony’s lens — subtly, intimately, incisively — captured the lived realities of people the mainstream media overlooked.

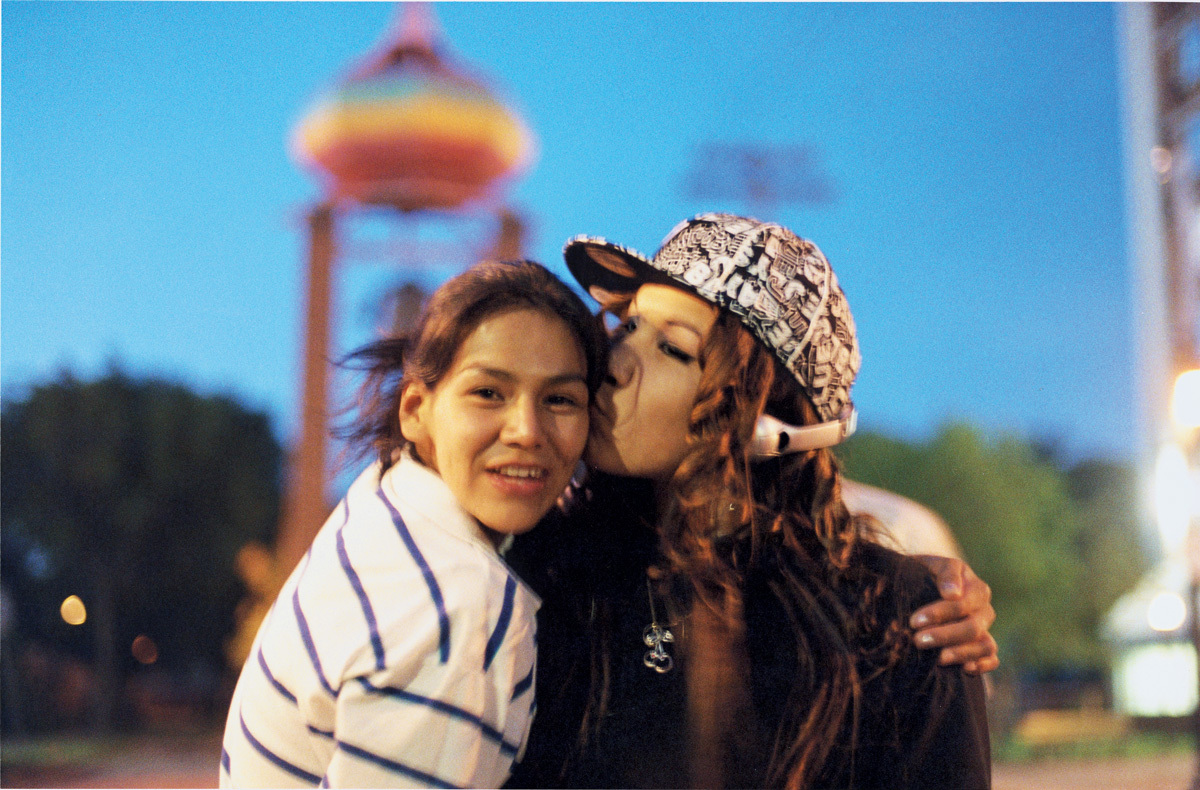

Zielony’s photography is not the cataclysmic war photography of Magnum, however. It is a meditation on life at the margins, a document of disillusionment, disenfranchisement, and disempowerment. If states, international relations, and wars form history’s A-side, then Zielony’s eye remains firmly focused on its B-side: stories rarely heard and always undervalued. His early work Car Park (2001) documents working class youth communities in Bristol’s estates; Trona captures the disenfranchised inhabitants of the Californian deserts; Manitoba explores indigenous communities in Canada; and Jenny Jenny — one of his most complex and ambivalent series — captures the multiplicity of identity cultivated and performed by sex workers in a Berlin brothel.

The Citizen (2015) made waves at the Berlin pavilion of the Venice Biennial last year and earned Zielony a nomination for the prestigious Deustche Borse Photography Prize. A photo series accompanied with printed newspapers, it documented refugee activists in Germany, shifting the focus from the Mediterranean, and broadening the scope of investigation to depict identity in diaspora, the unique struggles of refugees in their destination country, and the multiple forms of resistance led by activist movements. The portraits in The Citizen brim with a certain dynamism: one shot captures a woman reaching her right hand up the gnarled bark of a tree, her scarlet red nails disrupting the earthy tones of the image. Throughout, there’s a sense of movement that figures, aesthetically, the politics that drove the project.

“I didn’t want to portray people in a victimized or marginalized position,” Zielony explains, “so I decided to work with people who themselves had decided to become visible in the public sphere. They were demonstrating and organizing protest camps, even though they were working from a very difficult position — without papers and so on.” In capturing something more than bereft, tear-sheened faces or dehumanized queues of refugees in search of asylum, The Citizen explores agency where many others simply depict disempowerment.

The series is a shift in Zielony’s work: if the urban decay of his early work often looks at boredom and ennui of those capitalism left behind, The Citizen offers action and resistance. While Angela Merkel’s open door policy to refugees earned the acclaim of the Left, the reality of settling as a migrant in Germany was rarely heard. Refugees were restricted to specific towns or cities, their ability to work was limited, and the chance to study was non-existent. Young asylum seekers floundered without the freedom to build new lives. “The situation is improving,” Zielony notes with characteristic optimism, but largely because of the struggles of refugee activist groups like Lampedusa in Berlin, not the fading goodwill establishment.

While boredom might have been replaced by action, The Citizen nonetheless explores the enduring conceptual issues that have preoccupied Zielony for almost two decades. Pitched somewhere between photojournalism, documentary, and art, the series retains a degree of aesthetic continuity with his past work and poses the same conceptual questions. “It’s about how art can relate to politics, how politics can relate to some kind of reality out there,” he explains, a reality that photography is best placed to capture. “What stands out about photography is the direct link to reality and the way we receive the world with our eyes,” he adds.

Yet if his work reflects on the immediacy of reality and the vicissitudes of lived experience among the marginalized, it is also distinctly reflexive — an investigation into the medium of photography as much as the subjects he captures. “What is the special potential or responsibility or history of this medium?” he asks. What can be shot, how it can be shot, how it might be contextualized and how it should be distributed echo throughout the series; the newspaper accompanying the work is but one way of rendering such questions more explicit.

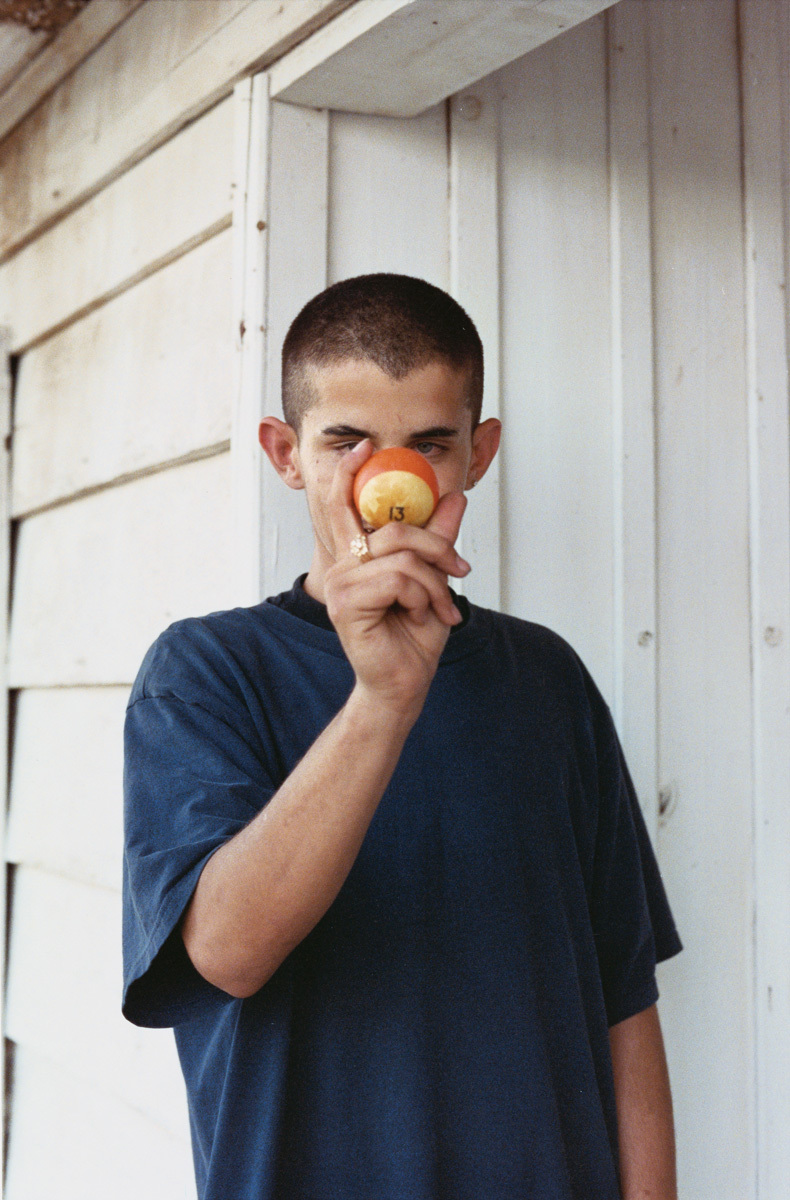

Perhaps the real charm of Zielony is his humility — his belief that the photographer is not some authoritative, objective observer, but a collaborator with his subject. “I have become more and more interested in what kind of poses I can evoke through my presence,” he says, “and what these poses mean to me maybe, but also where they come from in terms of the subconscious of the people I photograph. It’s about what is created through the meeting between me and the people I photograph, and how this relates to their imagination, or, let’s say, their idea of identity.” The process is collaborative, a dialogue between camera and subject that makes his work so vital, and so resistant to the petrifying stasis of much photojournalism.

At the heart of The Citizen, and Zielony’s work more broadly, is the perennial question over photographic realism. “I don’t know if it’s a word that exists,” Zielony says with a warm, disarming laugh, “but I am interested in self-staging — how people stage themselves within a public space.” He rejects the idea that any photograph is neutral, entirely without posing, and plays with the limits of documentary in each new series.

Whether in the self-conscious performance of sex workers inhabiting multiple roles and shifting identities in Jenny Jenny, or the alternation of candid and composed shots in The Citizen, Zielony poses the question of identity in all its complexity. His forthcoming project, an exploration of the power of the mask, looks set to be as challenging as his last.

Credits

Text Edward Siddons