Teenage boredom looked slightly different in the late 70s and early 80s. Put simply, no one had an iPhone. Kids hung out, they drank, they smoked, they stared pensively into the distance. Evidently they weren’t as terrified of being bored as today’s teens. They didn’t have Instagram delivering hilarious memes to them while they waited for the bus; they didn’t have Facebook to notify them about an event they weren’t attending while they watched TV; they didn’t have Google Maps in their pocket to aid them in their search for their pal’s house party in the boonies.

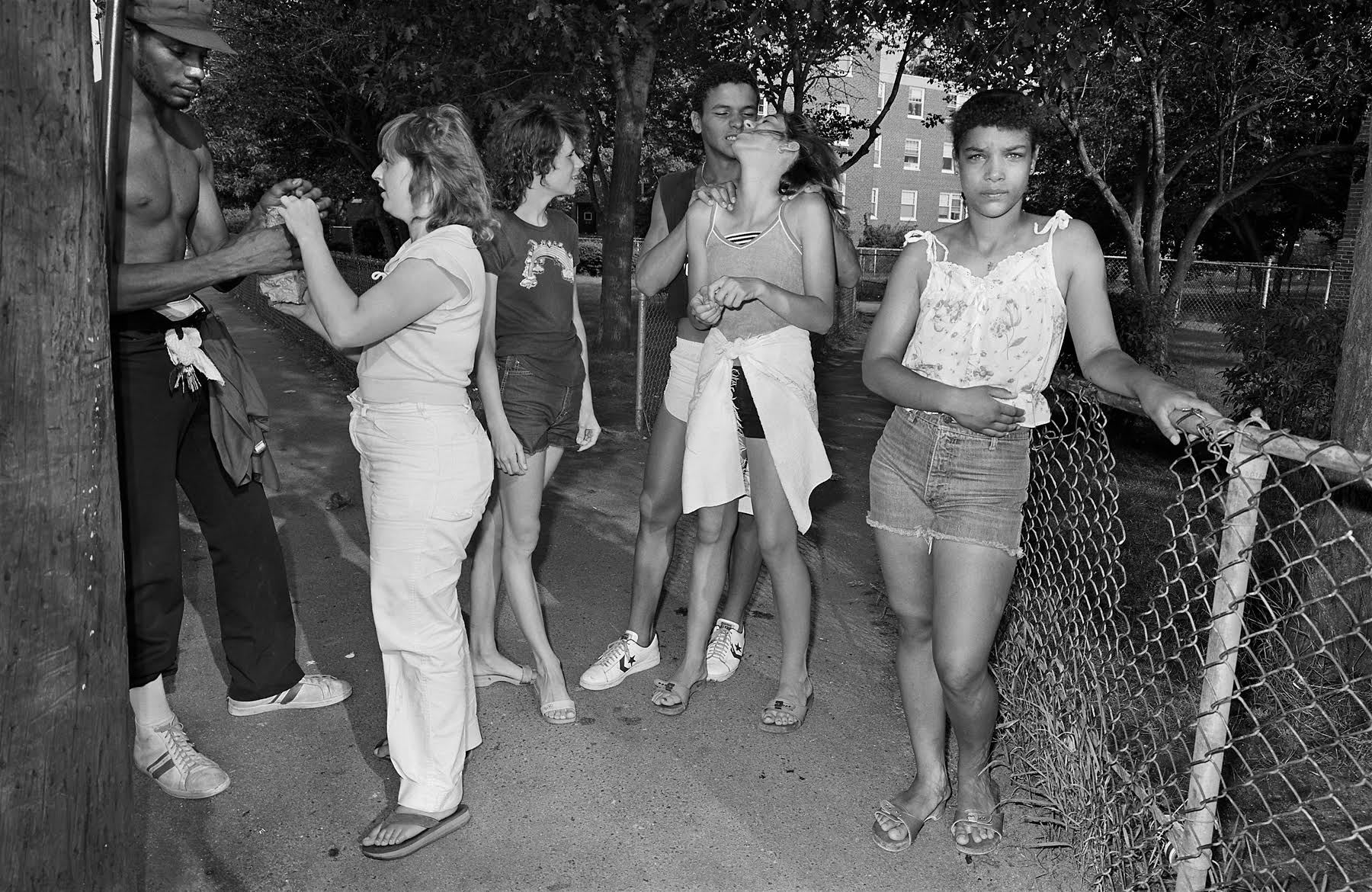

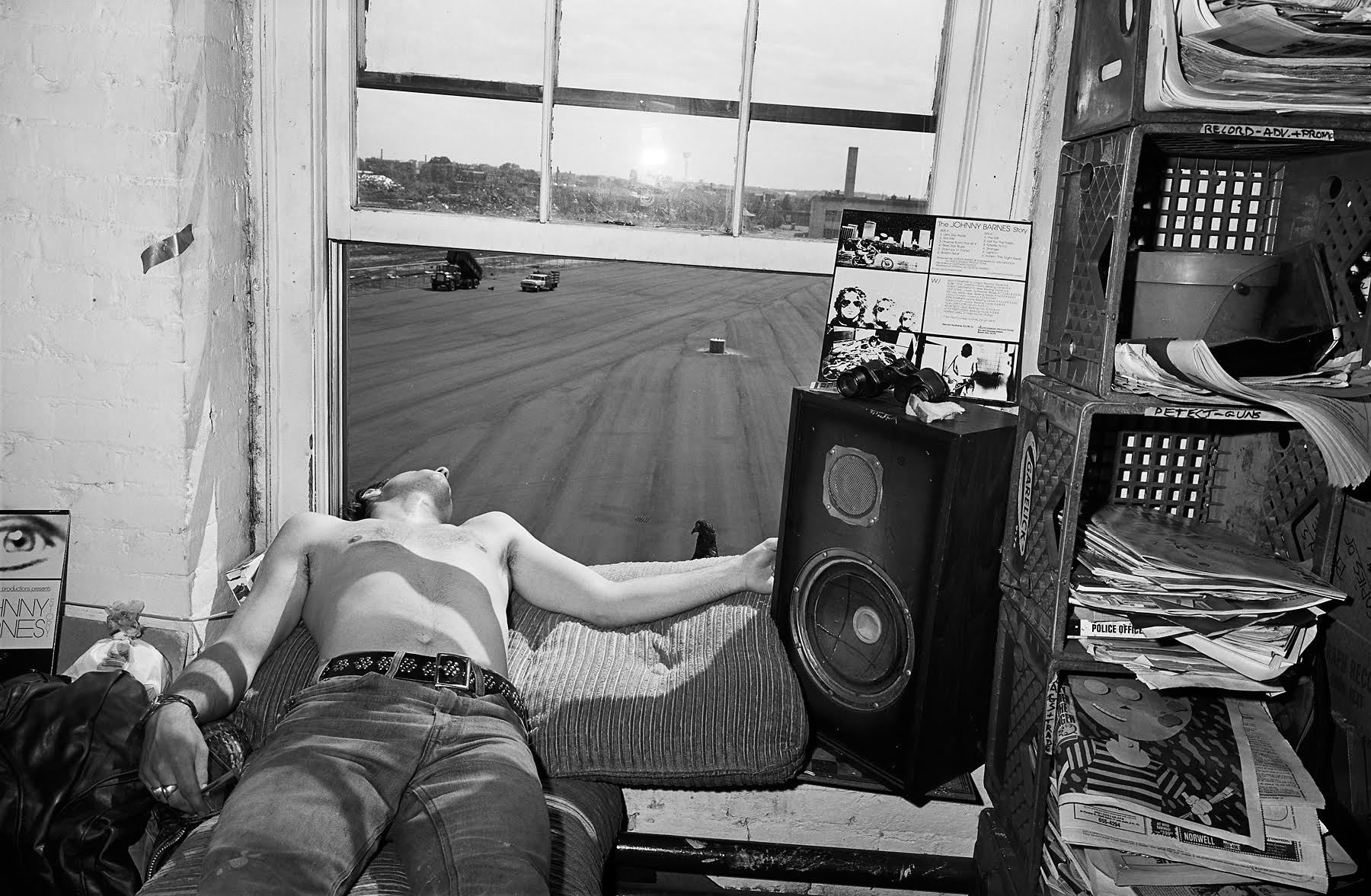

Ultimately, adolescent ennui today is best encapsulated by the image of a teen, head lowered, clutching an iPhone, battling boredom 24/7. Back in the 80s, however, it’d be something closer to what we see in the photographs of Sage Sohier. In her Americans Seen series, kids gaze out of the frame, lost for things to do, lost in their own inner worlds; they loiter, they lean on fences, they drink in the street. Sohier, then in her late twenties, ventured into various neighborhoods armed with a medium format camera and captured the daily life of pre-digital America. We called her up to get her thoughts on photographing teenage boredom, the innocence of the era, and her experiences exploring these sometimes-rough neighborhoods.

What was the idea behind Americans Seen?

I was a young photographer in my late 20s, and I was looking for people outside to photograph. It wasn’t that I had something to show exactly but, fortunately, in the editing process it became clear that there were certain kinds of things I was interested in. So despite the fact I was photographing all these disparate things, it ends up looking like a project that hangs together and I had a particular vision of America and of people hanging out. And I suppose I was discovering some of these neighborhoods in Massachusetts for the first time and just fell in love with them visually: the hilly mill towns and triple-deckers [a unique three-storey apartment building], things I didn’t grow up with in Virginia.

You photographed a lot of teens in these cities, and there’s a real sense of boredom in the way you catch them hanging out.

Yeah, and this was in the pre-digital era – no cell phones – so kids and teenagers were bored, and because of that boredom you’d find people trying to figure out things to do. Kids were playing, or teenagers were hanging out drinking or smoking. And you wouldn’t see that today; I mean, you don’t see people outside in the same way because they’re occupied on their computers or on their cell phones, which is both good and bad. I see it as a loss but it’s also nice that kids aren’t as bored. It’s harder to be a photographer these days, because you can’t just wander around and find people outside the same way.

With most of these pictures of children and adolescents, I became interested in a kind of performance aspect to it, where it looks like they’re acting a little bit. It seems natural but it also seems like they’re putting on a performance for themselves, in a way. And I feel like on those hot summer afternoons, when kids were bored, there was this sort of theatre of the streets that emerged from that boredom which was interesting.

One photograph shows a group of teenage girls smoking on a porch in South Boston, each of them lost in their own inner worlds. Were they oblivious to you?

They were sitting there in exactly the same way [before I took the shot] smoking and talking, and I think I probably spent about five or ten minutes with them, taking pictures; and often by the third or fourth picture they’d start assuming the pose they had before. I may have said to them, “You don’t need to look at the camera; I want to photograph you just the way you are.” But generally I always ask permission, because I was working with a medium format camera – a big camera – with a flash. I don’t sneak up on people, I always ask permission.

Being in your late 20s at the time, do you think it was easier for you to approach these girls and other teens?

It’s interesting and I’ve thought a lot about that as an older person photographing people. Young people seem fine with me now too, but I think it’s different. When you approach people now, everyone is so aware of the internet and YouTube, whereas back then, there was an innocence. There was less paranoia or fear then there is now, especially in the US where people worry about their kids being abducted. I see the pictures as a collaboration, and people seemed open to collaborating with me. If people asked me “what for?” I would say, “I’m an art photographer and I’m doing a project on people outside and hanging out.” People didn’t really know what that mean, but they were okay with it.

On a personal level, did you feel like you could relate to the teens, perhaps from a more reflective point of view?

Oh sure, of course. The picture is as much about me as it is about them. It’s a strange collaboration where it’s in some sense a true picture of them and in some sense a true picture of me and how I’m feeling. And then of course when the pictures are out in the world other people see something totally different in them. I’m always surprised when a friend looking at a photograph says, “Oh, that makes me so sad,” and I’m thinking, “this is not a sad picture!” Photographs are almost like a projective surface and people see their own experiences. That’s part of the power of photographs.

The shots date back to the late 70s and early 80s. What are your main memories of that period and those neighborhoods?

Back then I was struck by the beauty of things which aren’t inherently beautiful: these old brick mill buildings, triple-deckers, vacant lots, tree stumps, basketball hoops. I saw them as this wonderful stage set for making these portraits. There was something wonderful about wandering around looking for people, and I had the privilege of getting lost, which I don’t have anymore. It’s funny because even though I could easily not turn on my GPS, of course I do, but back then you really were out there on your own, you were lost, and you’d discover unexpected things and that was wonderful.

Were you ever scared, going into some of the rougher neighborhoods by yourself?

I was scared. There was one time when some teenage boys came up and grabbed my camera and for some reason I had a grip on the right-hand side and I managed to hold on to it. And then someone saw them, some parental type, and yelled at them, so it was threatening but not that threatening. And then, with the picture of the boys drinking beer, I did feel a little threatened. That was in a project in South Boston and here were these boys drinking, and I remember thinking, “Sage, you really shouldn’t do this; this is not smart.” But I couldn’t resist because they were so interesting. They were a little lewd and I had to deal with some of that — I was a young woman at the time — so it was a little uncomfortable, but it was okay. There’s something about being out there on your own and feeling a little lost. In some ways, it’s more conducive to discovering things. The most pleasurable thing about being a photographer, for me, is not the product — which of course is important and why you do it — but it’s really meeting all these interesting, strange people. I’m grateful that photography lured me out of my comfort zone and into other people’s lives in this wonderful way.

Sage Sohier’s Americans Seen photobook will be released in 2016 by Nazraeli Press.

Credits

Text Oliver Lunn

Photography Sage Sohier