Stripping will forever be defined by Paul Verhoeven’s 1995 tour de force of trash, Showgirls, in which our hero Nomi Malone is swallowed up by a Vegas Wendy House of knackered glitz, reptilian personae and sweat. The movie is a gloriously gaudy exotic dance fantasy, but what of the small-town reality? Two shows opening this month — at New York’s Higher Pictures Generation and Magnum Photos in Paris — focus on unseen colour pictures from Carnival Strippers, a series by the Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas, offering a visceral yet tender, historic counterpoint to Paul Verhoeven’s hard, high-octane camp.

In the summer of 1972, fresh from Harvard, the 24-year-old Susan took a road trip across America, planning to photograph circuses and state fairs with the immersive kick of Frederick Wiseman’s 1967 documentary Titicut Follies on her mind (the movie was about a patient-led talent show held at an inhumane correctional facility). In Maine, Susan encountered two large tents advertising “men only” girl shows and spent the next few summers travelling to small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina to record what happened on and off the makeshift stage. Interviewing the strippers themselves, their managers, and their families, the resulting body of work integrates numerous ideas of being a young woman in a period of early feminist thinking. She says, “I was filled with questions like any woman of that time about women’s liberation. I was wondering who I was in relation to these working women with the privileges I had. It was a really intense set of questions that I think I’ve carried with me through my life.”

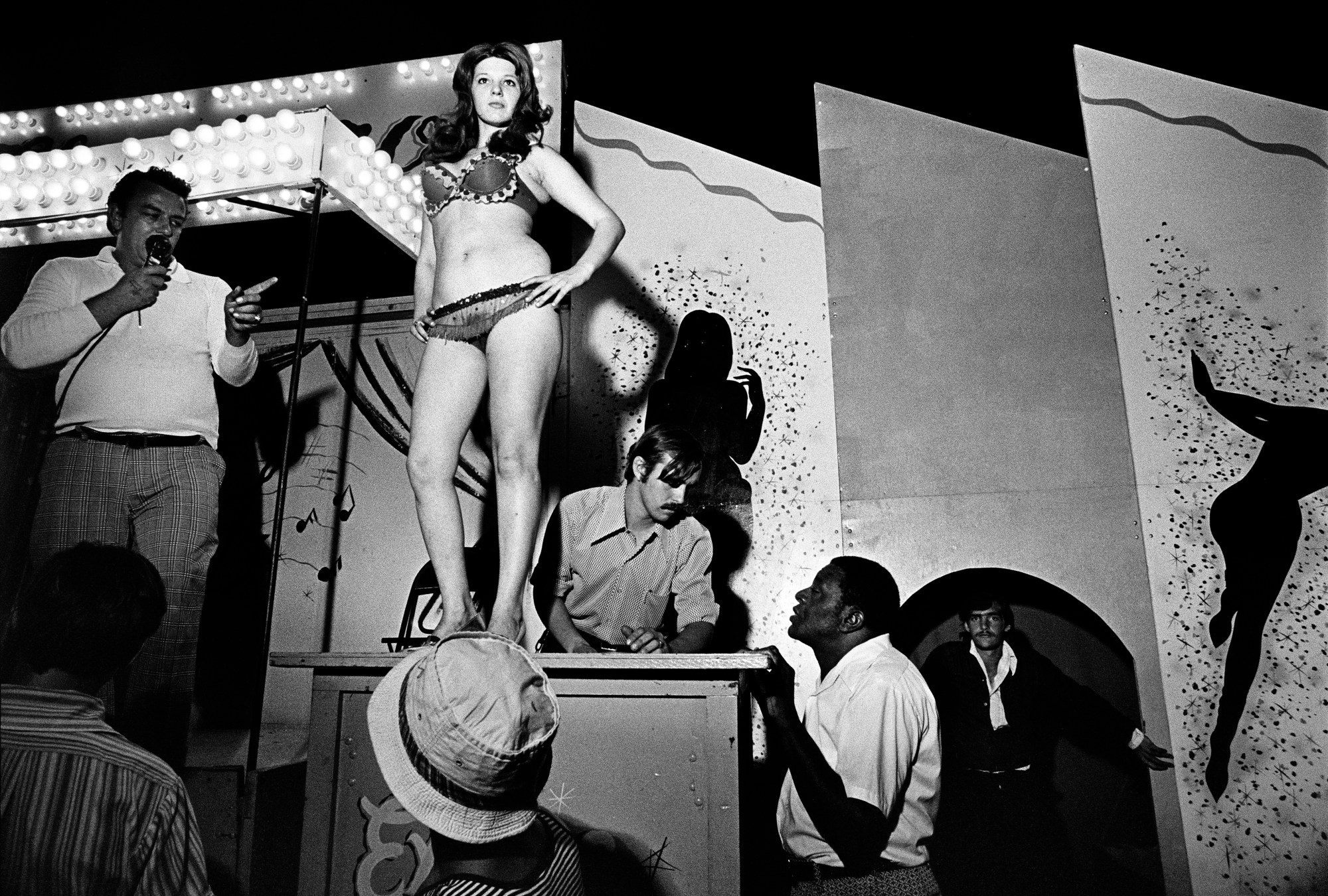

Originally published as a book in 1976, Susan’s black-and-white photographs of strippers performing to masses of gawping men reveal the struggle for independence in a complex era of change. They uncover the same anxieties that crowd every scene of Showgirls, albeit without the movie’s glossy machismo. In both is the same yearning for recognition. The desire to be seen.

Susan is best known for her coverage of the insurrection in Nicaragua in the 1970s and her documentation of human rights struggles in Latin America. Carnival Strippers is really a body of work about belonging. The monochromatic palette of the original book reveals the softness of the women’s bodies in a way that blurs their tough conditions. Cramped backstage areas lit by a single lamp seem immediately more cinematic. The black-and-white images are somehow more beautiful, more forgiving of their circumstance, than their colour counterparts. “Black-and-white was sort of the way we saw the world,” Susan says. “War was [always] pictured in black-and-white; I mean, how could you possibly see the blood? I didn’t invent shooting that in colour but, nonetheless, I was criticised heavily for it at the time. You’re talking about the romance of black-and-white, but people claimed my colour Nicaragua pictures beautified war.”

The colour images from Carnival Strippers expose a new layer of meaning, revealing a kind of tawdriness of the curtain or the blue tinsel. Hastily stitched together clothes. Bodies that are in bloom. The women in them hold us in an unflinching gaze.

Feminists at the time perceived the girl shows as exploitative places and framed the women as victims. Susan was more interested in recording how they were seen within their own world. In order to gain access into the tents, she performed a “mock man flasher act” so she could migrate through the various physical spaces amongst the male patrons. It was her way of rendering what she saw as a kind of ethnographic process. “I was drawn to know what motivated them. Partly, but not wholly, their reasons were economic. Yet they revealed other aspects of what it meant to be a woman and to have to use their body in that way. What I saw from inside was that the girls pictured themselves differently. I felt a tension between how they perceived themselves and how society was looking at them — not just by men but by the women’s liberation movement.”

Carnival Strippers Revisited — a new and expanded edition of the original book — has just been published by Steidl and includes ephemera collected by Susan at the time she developed the project. “I’m someone who has always been interested in revisiting work and the process, the relationships,” she says. “My only regret in this particular moment is that I was unable to find any of the people I came to know then. Those women have now passed and there’s some sense that this is unequal, and I wish we were in it together. What I have as a ‘together’ is the audience — and a new audience — coming to it fresh. I’m looking back at contact sheets and rediscovering colour, revisiting transcripts that I obviously edited at the time. I’m trying to understand the universe I was in the midst of. I’m not sure what I think about the colour yet. I’m just enjoying reflecting on it.”

Susan Meiselas: Carnival Strippers Revisited will be at Magnum Photos in Paris from 17 February 2022 to 30 April 2022 whilst Susan Meiselas: Carnival Strippers Color, 1972-1975 will be at Higher Picture Generation in New York from 19 February 2022 to 16 April 2022. You can also purchase the book from the Magnum Photos website.

Credits

All images © Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos.