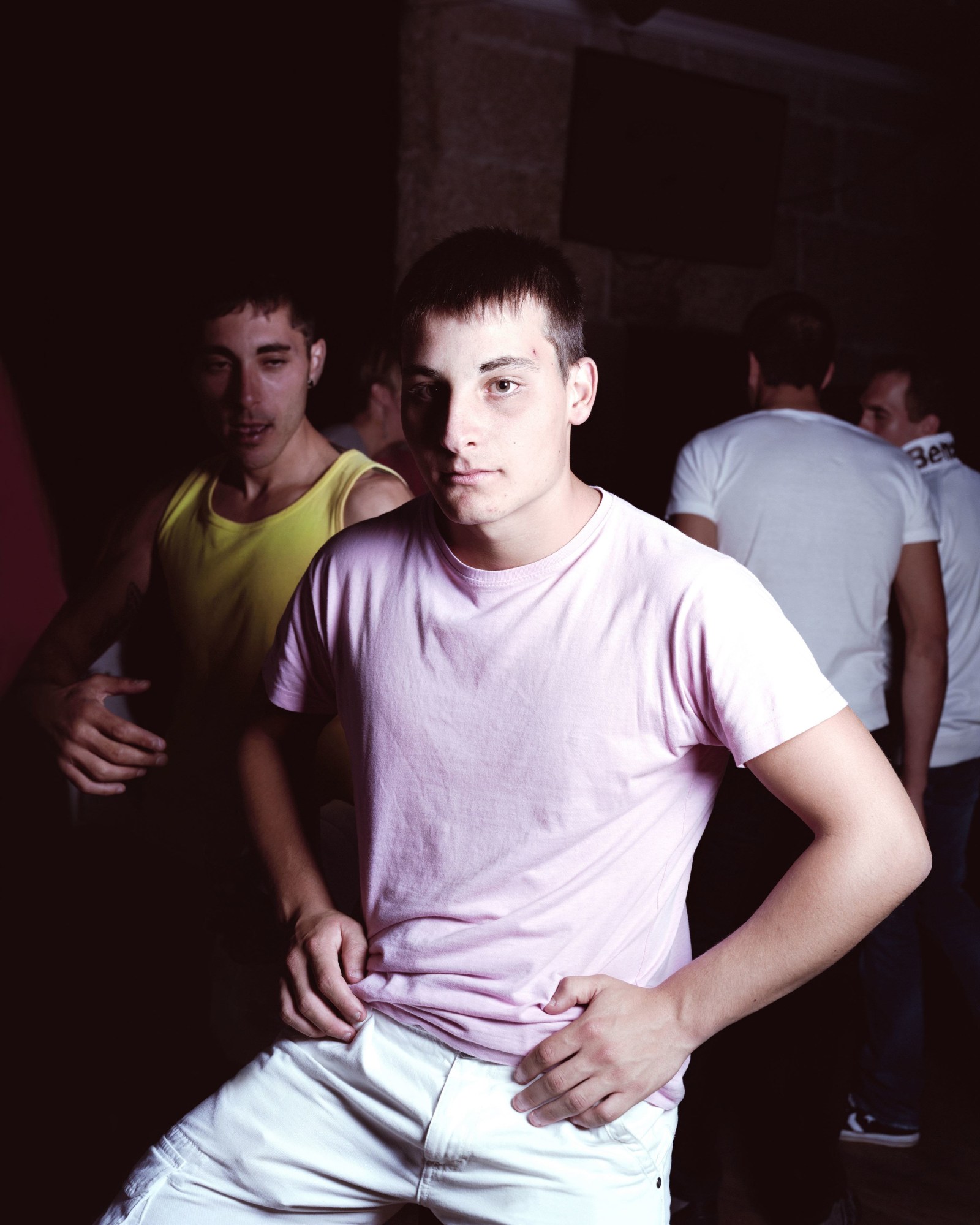

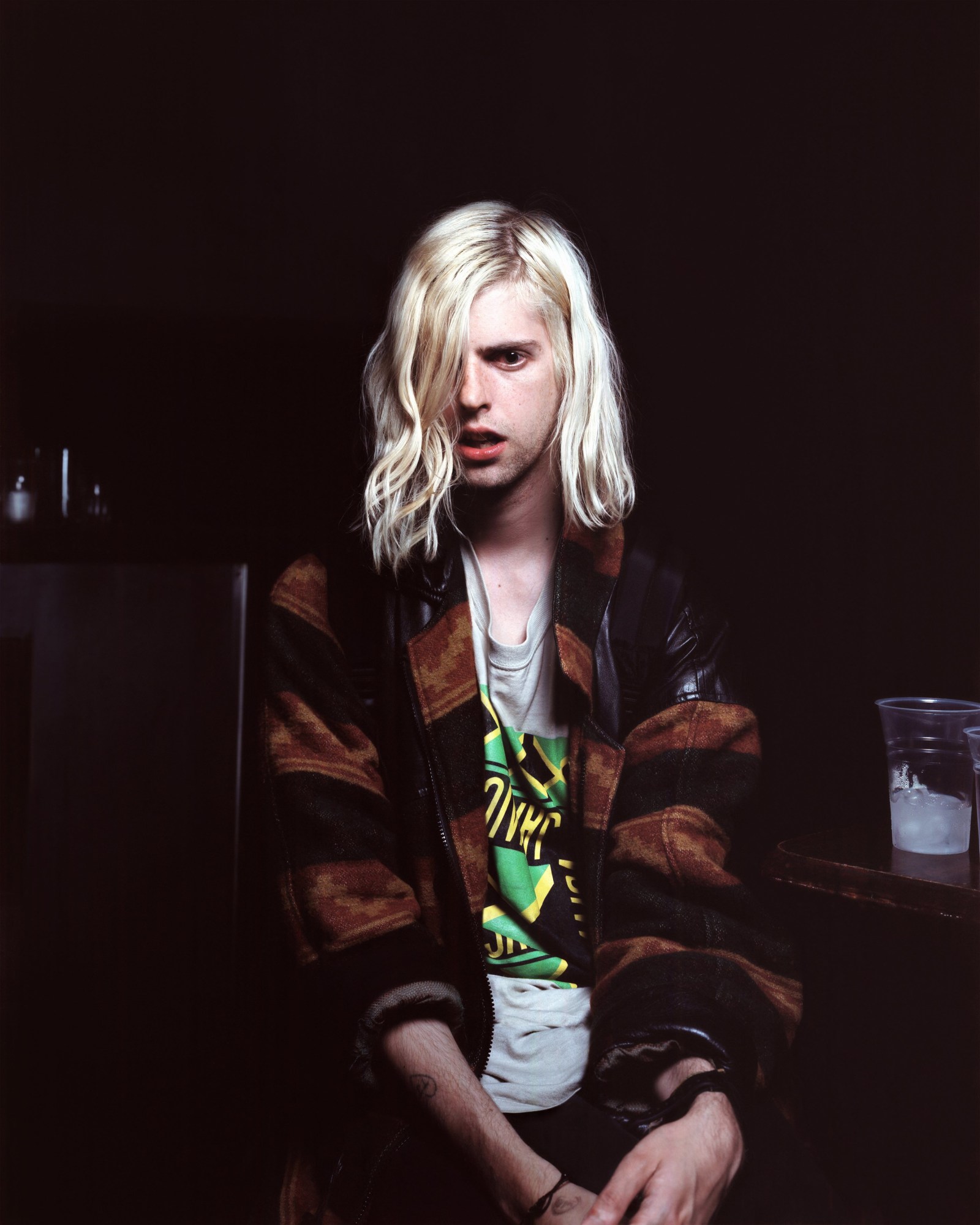

Jesús Madriñán has created an improbable hybrid: he has taken conventional portrait photography and transposed it into a nightclub setting. Spanish-born, Madriñán grew up with antique-dealer parents, surrounded by artifacts and classical paintings. Later, he studied fine arts in Barcelona and London. In his photography he reaffirms the nightclub not just as a place to party but also as a place to simply be — which was key for Madriñán himself as he was coming to grips with his identity and finding a refuge in nightlife.

Madriñán’s makeshift, mobile pop-up studio draws out psychological clues about the strangers who spend their nights in the dark of the club. His initial series “Good Night London” (2011) continued with “Boas Noites” (2013), photographed in the rural Spanish villages of Galicia. Now “Dopo Roma (After Rome),” the series Madriñán is working on presently, draws the work to its natural conclusion; its images, taken outside the club, show night thinning to daybreak. Madriñán shot these most recent portraits during an artist residency in Rome and showed them at Unseen Amsterdam this fall.

Although he photographed the three series in different countries (UK, Spain, Italy), the concept behind each set of images is the same: to provide a study of body language and perceptions of the self while out on the town — consciously constructed or not. Here, Madriñán discusses upending the prototypical studio environment and portraying youth in an authentic way.

How did the initial idea come about for “Good Night London”? Why was nightlife attractive to you as a photographer?

Growing up gay in a repressive environment, nightlife was the place for me to take shelter, even if I never felt totally comfortable in it. It meant hope, the chance of meeting someone, the comfort of being yourself. Still, there was always a sense of frustration in me at the end of every night. I felt strongly attracted to nightlife, but at the same time I didn’t completely understand it. I remember sitting alone at a nightclub, watching all around, feeling moved and inspired. The image of all those kids dancing around me was the beginning of everything.

What’s your process for taking images in clubs?

The portrait series were taken in several nightclubs that I used to frequent with my friends. I find it interesting how these artificial environments work; they’re a key element in the way teenagers construct their own identities. I tend to work with a large format camera and I set up an actual studio in the middle of the dance floor. Conventional studio photography is thus taken out of context. The calm of a studio is substituted for the noisy nightclub, where the sitters improvise according to whatever narrative they want. They are always strangers, and how they behave in front of the camera corresponds to how they want to be seen. For me, portraiture is an intimate relationship between the person portrayed and the lens, which happens to be the audience.

How different is taking a portrait in a public space to taking one privately?

That is part of the game. My work centers on the paradox of capturing life’s spontaneity, but using dependable techniques taken from the studio. It’s that contradiction of using meticulous skills applied to inevitably chaotic situations. A certain technique and a certain kind of lighting can transform reality. Appropriating Hiroshi Sugimoto’s words— [“However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real”] — I would say exactly the opposite: no matter how real a situation might be, once photographed, it is almost artificial.

You’ve lived in various cities; how different are people’s attitudes about being photographed in different places?

It’s true that people behave slightly differently depending on the place where they are from, but I have always worked in Western cities, so attitudes are not so different in the end. I always give my business card to the people I photograph and, for example, I found it strange that almost nobody in the UK and Spain contacted me after to ask for his or her portrait, while in Italy almost everyone wrote to me wanting to see the resulting picture.

Which other photographers and artists do you admire?

I love Felix González-Torres’s work, and I like Angela Strassheim, Alec Soth, Marlene Dumas, Nadav Kander, Nikolay Bakharev, and Sophie Calle. I also enjoy painters such as Emile Friant, Antonio Gisbert, and Sánchez Cotán.

“Dopo Roma (After Rome)” continues the theme of “Good Night London” and “Boas Noitas,” but outdoors, post-clubbing. Why this shift?

Yes, “Dopo Roma” captures subjects outside the clubs as parties begin to slowly wind down. I wanted to play somehow with the audience, not giving specific answers, presenting subjects against a dawn sky. The fact that I have worked in different cities responds to my own life, as I had to live in different countries, but I believe all these projects also work together.

In the introduction to “Boas Noitas” you describe your work as depicting “youth devoid of any idealization” — can you elaborate on this?

There is no idealization, on my part, in the way I present my subjects; it is a real and tangible youth. I give them the opportunity to decide how they want to be seen, so maybe, in fact, the idealization is on their side.

Even in your commercial work, portraiture is always the focus. Why is this format meaningful to you?

I’m interested in people from an anthropological point of view, and I understand portraiture as a document with a potential to give testimony of the society of a time. There is a huge capacity in each portrait to convey things. Besides, I see myself in all my portraits, so they allow me to better understand myself.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Jesús Madriñán