On April 29, 1992, South Central Los Angeles erupted. The four white officers charged with the assault of Rodney King, a 26-year-old African-American whose vicious assault was captured on video and caused renewed focus on endemic police brutality, were acquitted. A spark hit the tinderbox of poverty, oppressive policing, and racial injustice and riots tore through the city. In the six days of unrest, 55 were killed, over 2,000 injured, and swathes of South Central were laid waste.

In the aftermath of the riots, Dana Lixenberg — the Dutch photographer recently nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize — was assigned to Los Angeles by the Dutch weekly Vrij Nederland to document the reconstruction of the city. During the trip, the creative seed of a new project took root, a series documenting life in the projects. This idea formed the foundation of a project which metastasized into a 22-year professional and personal engagement with the residents of one of South Central’s oldest housing projects documented in her book, Imperial Courts, 1993-2015.

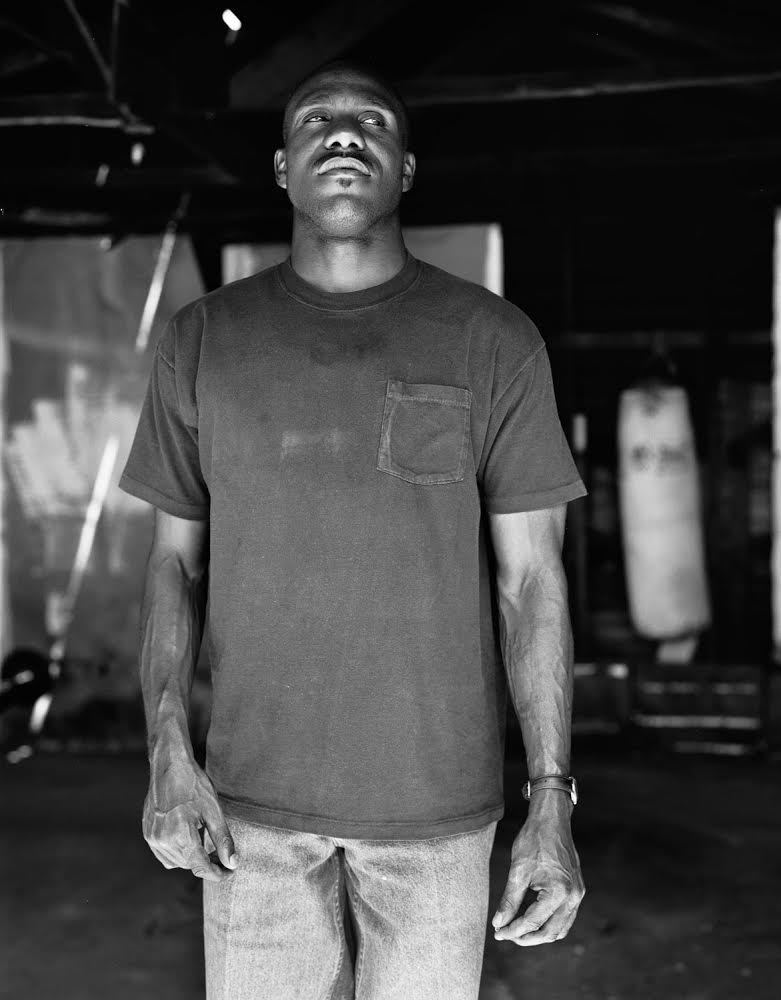

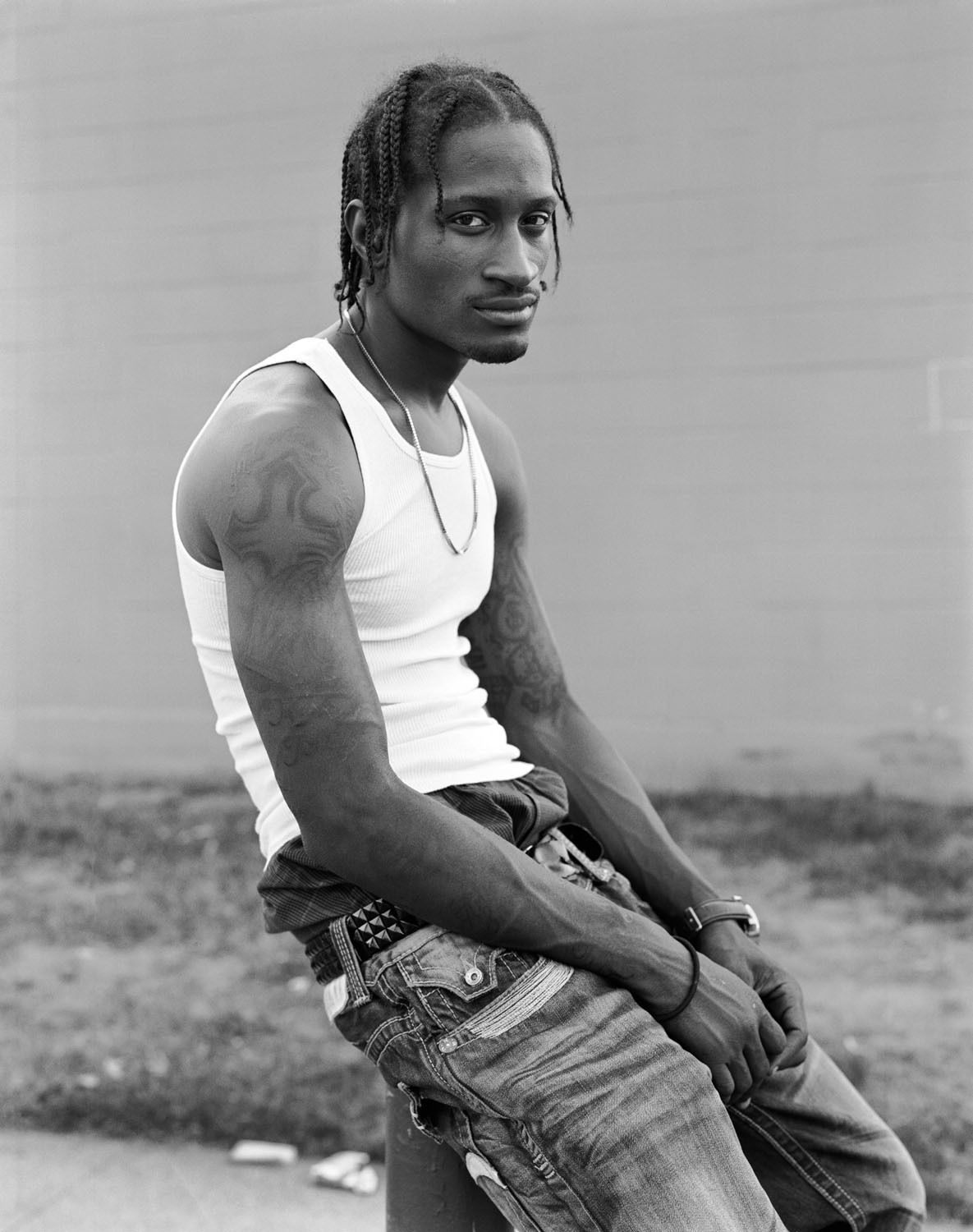

A monochrome epic, Lixenberg’s weighty volume constructs stark social documentary through ineffably intimate portraiture, presenting life at America’s margins across a time-span such projects rarely receive. Less a series of snapshots than a symphonic homage to the spirit of community, the book offers not so much a history from below as a history from within. Her subjects — many of whom she now counts as friends — reappear across the years, some with new lovers, old friends, and teenage children. Others don’t. The specters of incarceration, addiction, and gang violence haunt some of the work’s notable absences, gesturing at stories left untold.

“After the riots, the neighborhood was portrayed as a war zone,” Lixenberg explains over a call from her Amsterdam apartment, “somewhere you don’t enter as an outsider, somewhere that’s impenetrable.” The slew of media coverage during and following the riots abounded with shoddy reporting, explicit racial bias, and myopic analyses of the issues at stake. “I wanted to go and make this undramatic series of portraits of gang members because they were so mythologized,” she adds. Yet entering the community proved difficult.

“I wasn’t naïve about being white,” she recalls, “and of course there were questions about how I could relate to lives that were so different from mine. But as a photographer, you have to go beyond that. In many ways, I think being foreign helped in some respects — not being a white American, I perhaps didn’t carry that specific history with me.”

Lixenberg’s previous work in L.A. had introduced her to The Black Carpenters association, a small collective of contractors and activists based in South Central who played a vital role in the reconstruction of the community. Their influence in Imperial Courts only went so far, however, and to move freely through the pastel-hued concrete maze of the projects, Lixenberg needed the blessing of the community’s kingpin, the late Tony ‘TB’ Bogard, OG of the PJ Watts Crips.

Bogard, who had renounced gang violence and turned peacemaker, later brokering a truce between the Bloods and the Crips to which Lixenberg was allowed access (but did not photograph), was skeptical. “I remember Tony asking, ‘What do we get out of this?’ I said I didn’t know,” she explains. “I’m still not sure if I know. I just hoped the photos would say something that mattered.” After a test shoot of his friend Malik, Bogard was reluctantly convinced and Lixenberg was allowed into the fold. Eventually, Bogard allowed Lixenberg to take his portrait. Less than a year later, he was shot dead by a member of his own gang.

A selection of the portraits from her visit in 1993 were published in one of the first issues of Vibe, a magazine that transformed Lixenberg’s career. In the 15 years that passed before she could find her way back to Imperial Courts with her camera (though she had visited in the meantime), she took era-defining shots of Tupac, Aaliyah, Biggie, Eminem, and Lil Kim, honing her portraiture to a fine art.

“Deep down, I felt something was unfinished,” Lixenberg explains. While in 1993 she had no inkling that the project would develop into the transgenerational history that it became, the Courts exerted a subtle but inescapable pull and her earlier shots had become artifacts within the community. “The pictures began to have a history of their own,” she says with a smile, “they began to mean things to people in the community. They became part of their history. They started asking if I would come back.”

When Lixenberg returned, it was continuity rather than change that struck her. I ask if life for the residents had seen any tangible improvements under Obama’s tenure. Lixenberg scoffs. “The conditions haven’t changed. The schools are still crap and people don’t get the education they need and deserve. The kids are bright, and have all this energy, but really nowhere to go with it.” She recalls that, in 2014, the apartment blocks were emblazoned with huge numbers. Confused, she asked the Courts residents why. They explained that it was so that the ever-present police helicopters could more easily keep tabs on their lives.

Even if the political conditions in the projects hadn’t changed, Lixenberg realized her project had to. “It wasn’t enough just to revisit and have some of the same people 15 years later,” she recalls, “I wanted to go back and focus on the newer generations, rediscover the community, get to know them in a different way and become more aware of the familial relationships and connections in the community.” While incorporating new subjects, she incorporated new media: in 2009, Lixenberg began recording audio from the residents talking about their response to the portraits, and in 2012, began shooting video that would form the raw material for a three-channel video installation and a web documentary.

This involvement from the Courts community, the persistent inscription of their agency in the work — from how they carry themselves in the portraits to how they contribute and participate in the video footage — is perhaps the secret to the work’s power and the key to how it stringently avoids the twin pitfalls of voyeurism or fetishization of African-American struggle. From the individual, large-scale portraits simply printed in the first half of the book to the photographic family trees denoted by collated thumbnails in the latter pages, a sense of duality emerges. This is a book that is not solely for a global audience; it is, in some sense, for the residents above all else.

The dual function of the work as both social documentary to outsiders and community history to residents poses broader questions. Who deserves to be recorded? Whose culture is allowed into the history books? Whose images live on? Imperial Courts, 1993-2015, is one contribution to righting that imbalance, and despite the elliptical gestures toward the oppression containing and molding life in Imperial Courts, injustice is not the enduring message, and the residents never become passive, traumatized subjects. Poverty, police brutality, urban decay and political, disenfranchisement might undergird life in the projects, but the community’s survival — itself a form of resistance — is here triumphant.

Imperial Courts, 1993-2015 was published in Amsterdam in 2015 by Roma and can be purchased here. Works from Imperial Courts and the three other photographers nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize will be exhibited at The Photographers’ Gallery from March 3 – June 11, 2017.

Credits

Text Edward Siddons