Back in 1965, a then little-known journalist Hunter S. Thompson made his name when The Nation published his essay “The Motorcycle Gangs: Losers and Outsiders”, championing the Hell’s Angels. Dazzling readers with his dexterous display of literary gifts, the self-proclaimed gonzo journalist penned a heart-pounding tale of crime for the modern age, transforming the widely reviled bikers into iconoclastic American anti-heroes.

Simultaneously defending, celebrating, and reinforcing the gang’s abject lawlessness, the story became the talk of the town. Two years later, he followed up with Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, a deft non-fiction novel that cemented a singular image of bike gangs in the American psyche. Fuelled by libertarian ethics and a nihilistic ethos, these white, working class hyper-masculine rebels and renegades were the heirs to their colonising forefathers who took what they wanted by force. Even after Hunter S. Thompson was beatdown by the bikers, bringing the book to a close, he couldn’t help but be enamoured by their brutality.

Fast forward half a century though and white bikers have been rebranded as “mature, upscale, upper class citizens who exemplify strong morals and American individualism”, according to researcher Jason Eastman, a sociologist at Coastal Carolina University, perceived by some as fine, upstanding family men who serve in the military, police, and fire departments or work in prominent white collar jobs. Meanwhile, law enforcement, which sees themselves in the badass white bikers, perceives Black bikers as a threat — despite the fact that as recently as 2015, white Texas motorcycle clubs engaged in a gun fight that left nine dead, 18 wounded, and 170 bikers arrested on charges of organised crime linked to capital murder.

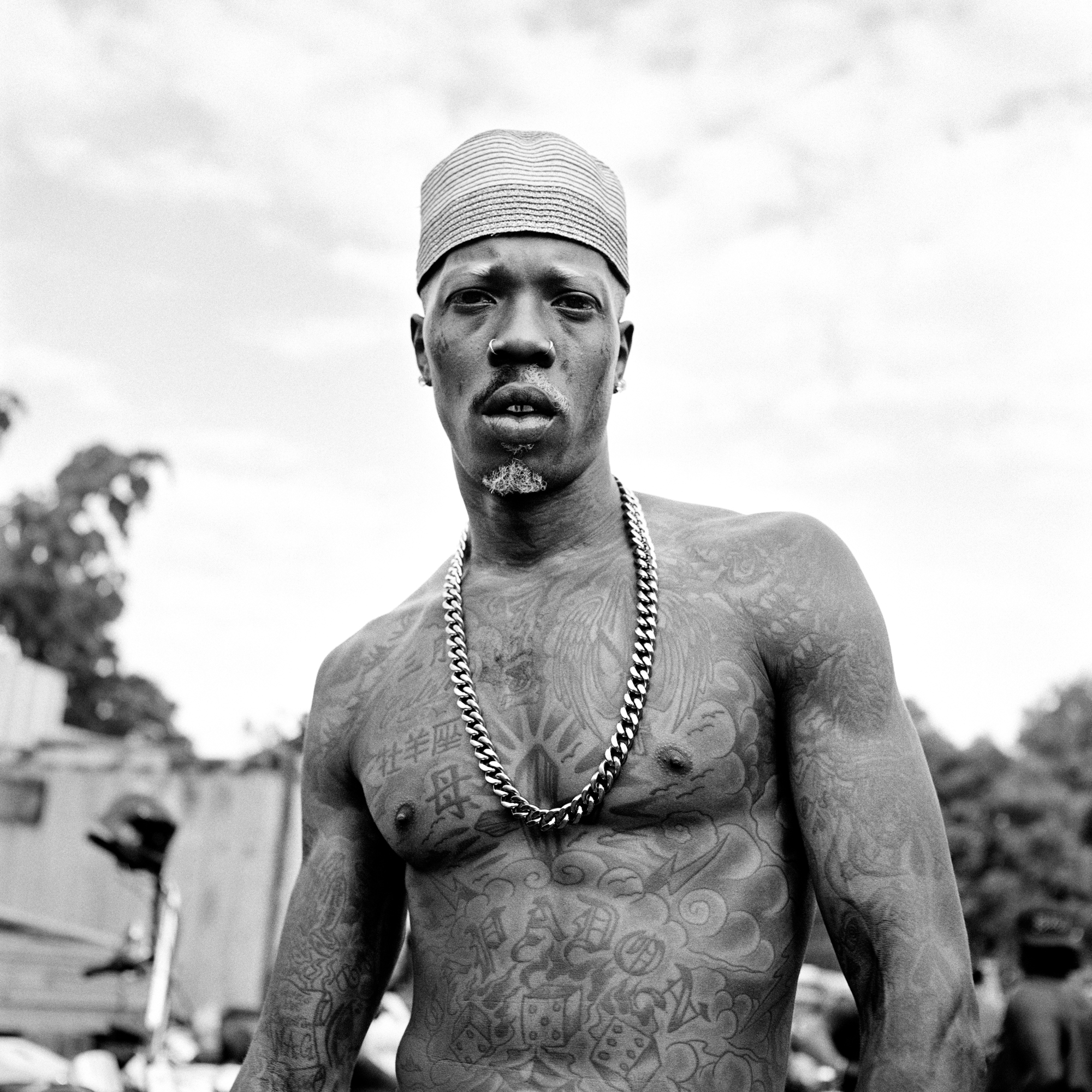

In the United States, when it comes to race, the gulf between perception and reality are profoundly misaligned. In 2014, New York-based photographer Cate Dingley became curious about the city’s Black motorcycle community, and started to ask around. After a woman dating a member of the Katz Motorcycle Club made an introduction, Cate spent the day at their Bushwick clubhouse, hanging out and making portraits.

“Afterwards, they told me they were going to a barbecue and invited me to come along,” Cate says. “I rode with them to a park somewhere in Brooklyn and there were hundreds of bikers from dozens of clubs already there.” After being introduced to the set, Cate spent the next year getting to know the Black Falcons, one of New York’s oldest Black motorcycle clubs. Established in 1962, the Black Falcons are committed to preserving their history and recognised in Cate her potential to contribute to their legacy through photography.

Once the Falcons vouched for her, Cate began connecting with other clubs. Over the next five years, she became deeply immersed in a world where bonds can be deeper than blood, weaving photographs and conversations with 10 bikers in her first book, Ezy Riders (The Artist Edition). A story of camaraderie and community, Ezy Riders is a portrait of the families we make for ourselves that stick together, through good times and bad.

“For us it’s like we have the same blood,” says Black Falcons member King Midas in the book. “We fight. We argue. We don’t like each other some days, we love each other. We hang out, we don’t hang out, we ride together, we don’t ride, things happen. But bottom line this is a family.”

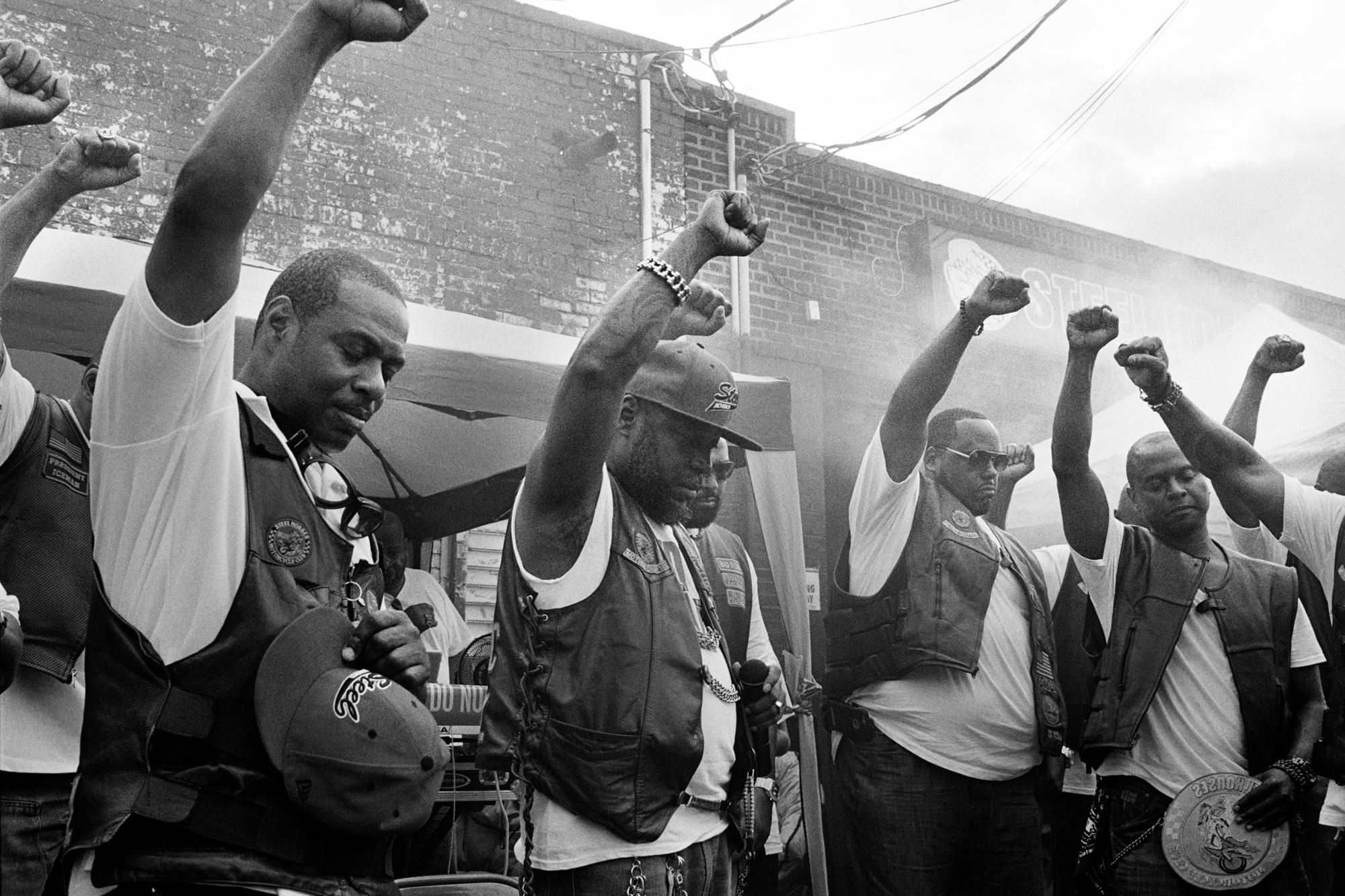

Whether attending bike blessings, charity runs, bikini bike washes, and anniversary parties, or just spending time in the clubhouses to observe everyday life, Cate lovingly chronicled the intergenerational ties that keep clubs united over the years. “They spend decades together,” she says. “They go to each other’s weddings and funerals, as well as that of their relatives. The club members bring their families to the events and everyone is hanging out. They babysit each others kids so the children all grow up with 30 or 40 aunties and uncles — how amazing is that!”

Although Black motorcycle clubs are a home for rebels, they are the exact opposite of anarchy. Although there are definite outlaws in the mix, Cate explains, “You don’t rebel in your club, you follow orders. There is strict adherence to tradition. The rebelliousness I am drawn to in the culture is the defiant act of breaking stereotypes. There’s great diversity within the scene, and they are very accepting and non-judgmental. It goes to show the passion and love for riding can touch every kind of person. In one club, the president drives an MTA bus and one of his members is a high-ranking banker. [Social status] is not important.”

But loyalty, integrity, and respect are important. The clubs offer a strong vision and organisation through hierarchical structures. Members value leadership and follow through, making them well positioned to uplift the neighbourhood. “Bikers are tough, but they’re also some of the most caring, giving people I’ve ever met,” says Cate. “They genuinely want to help the community because many times, that’s where they grew up. They’re uniquely positioned to do good because they know the people personally and are in touch with the specific issues happening around them.”

In Ezy Riders, Church Lady, pastor of the Taking It To the Streets Ministry, speaks about the importance of using her position to change the public perspective of bikers through gun give-backs, clothing drives, and family shelter support. “Community service is a very important aspect and should be in everybody’s lives,” Church Lady says. “If you live in the community, you are aware of the things that’s going on… and if there is any way that you can make it better, then that’s what you should do because this is where you live.”

The riders are also going through struggles of their own that make them sensitive to the issues facing the community. After serving 13 months in the Iraq War with the U.S. Marines, King Midas returned to the Bronx with PTSD. “For some of us the adrenaline rush is the peaceful place. When you’ve grown accustomed to it, especially if you were in a combat zone for an extended period of time, you’re used to being constantly on adrenaline,” he explains.

“So when it’s a stressful situation—I lost my job today—or, I’m beefing with my wife—kids are getting on my nerves—all those things for a lot of people it’s like—I’m gonna get on my bike. I’m gonna ride for an hour then I’m gonna come back and I can handle this…. Whatever was bothering me, I left it—90 miles ago, an hour ago, you know what I’m saying? That’s my peace.”