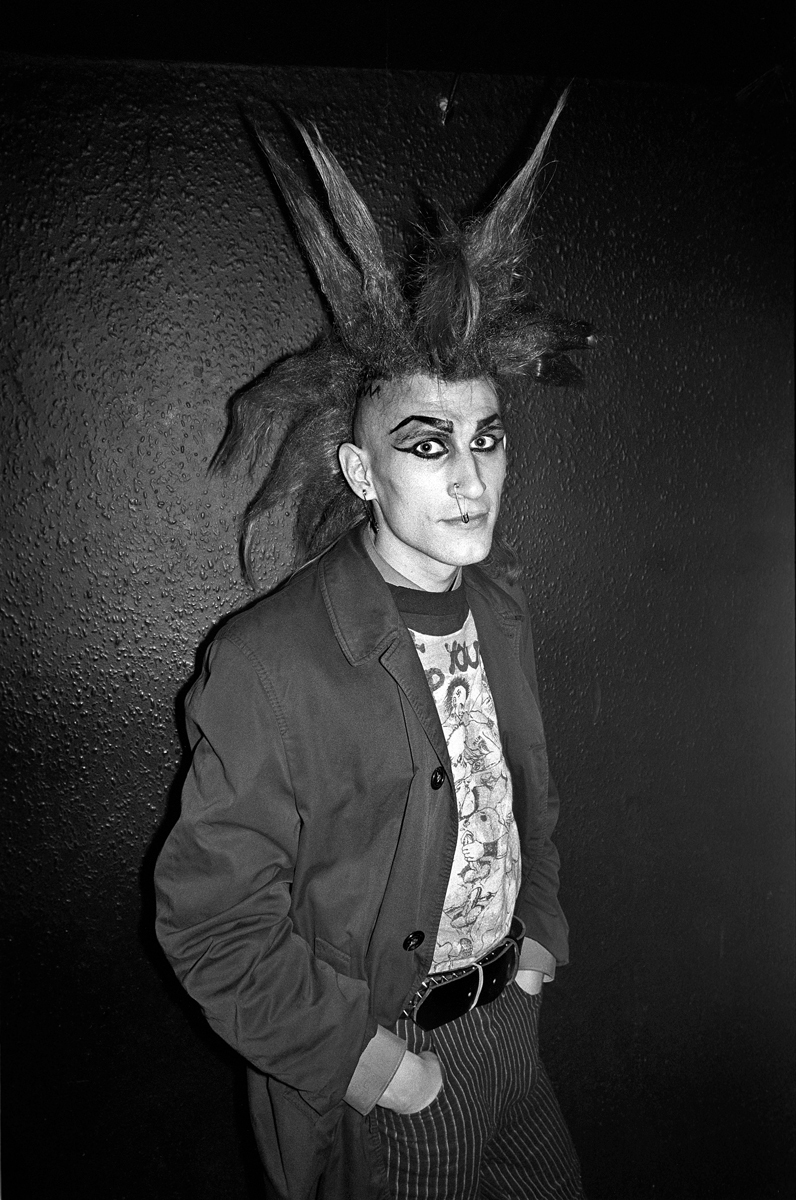

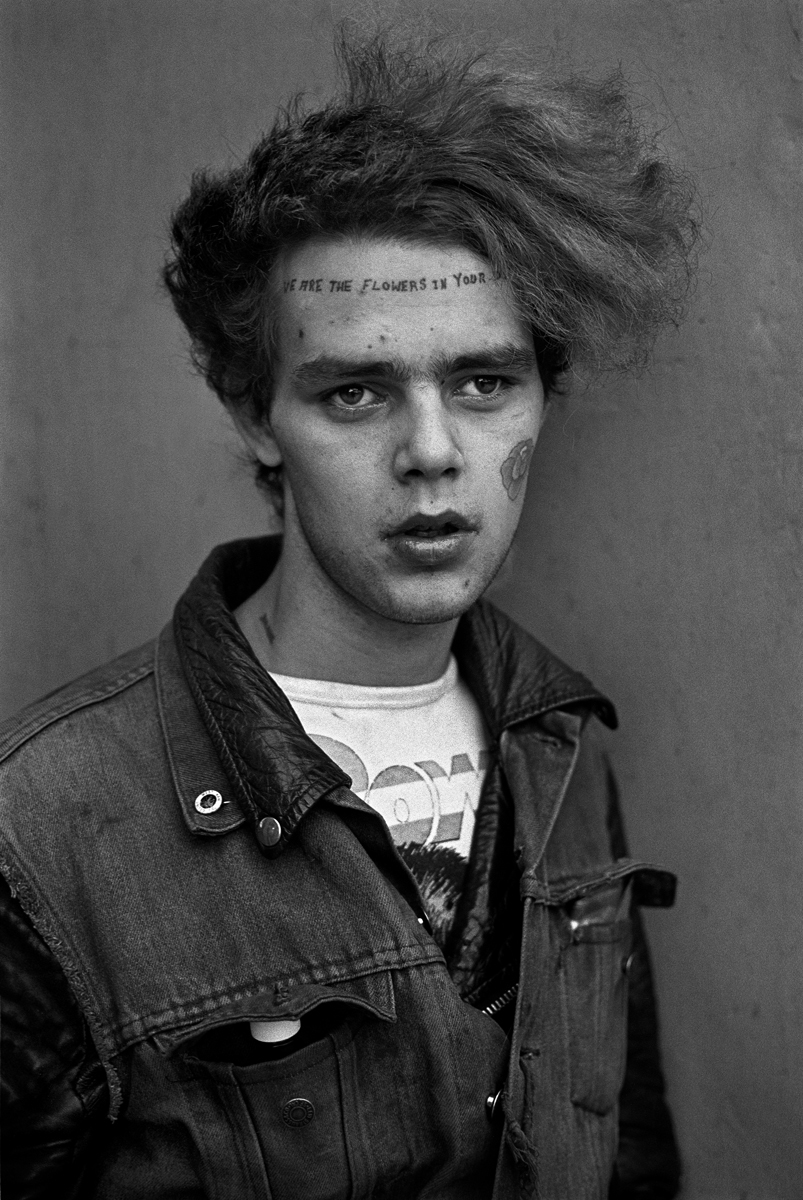

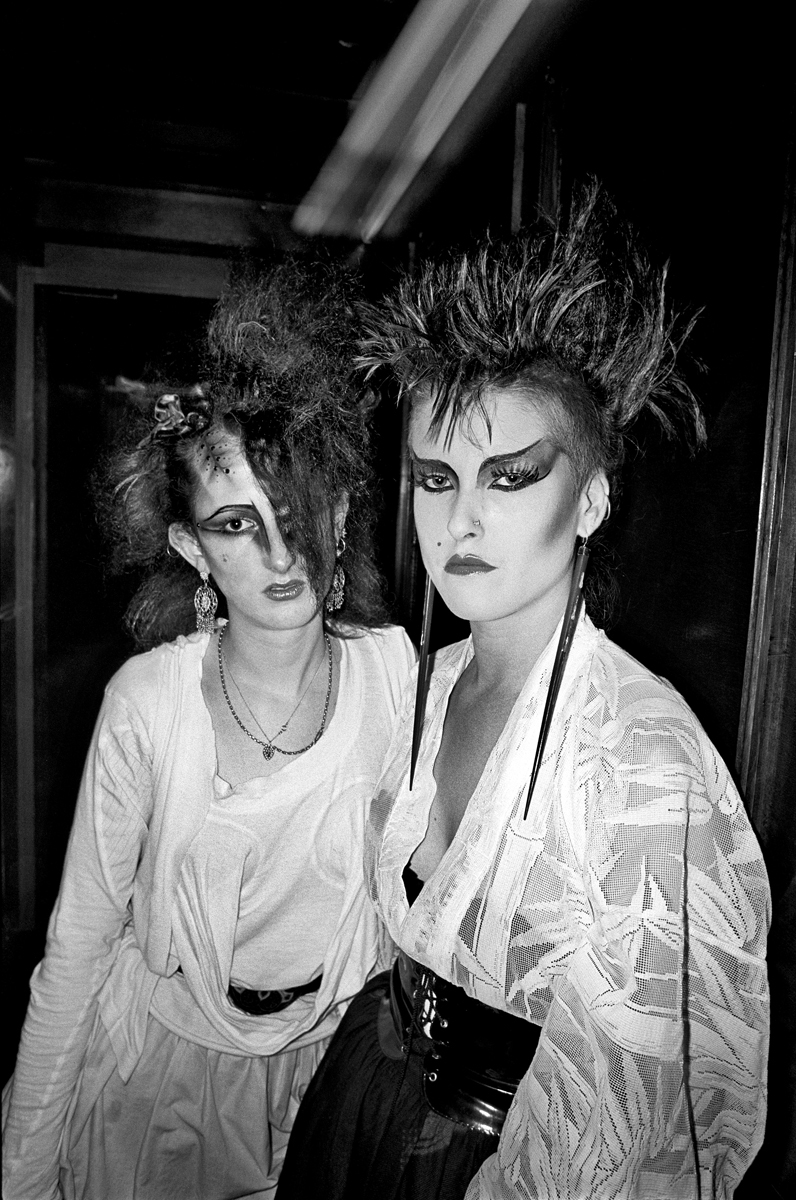

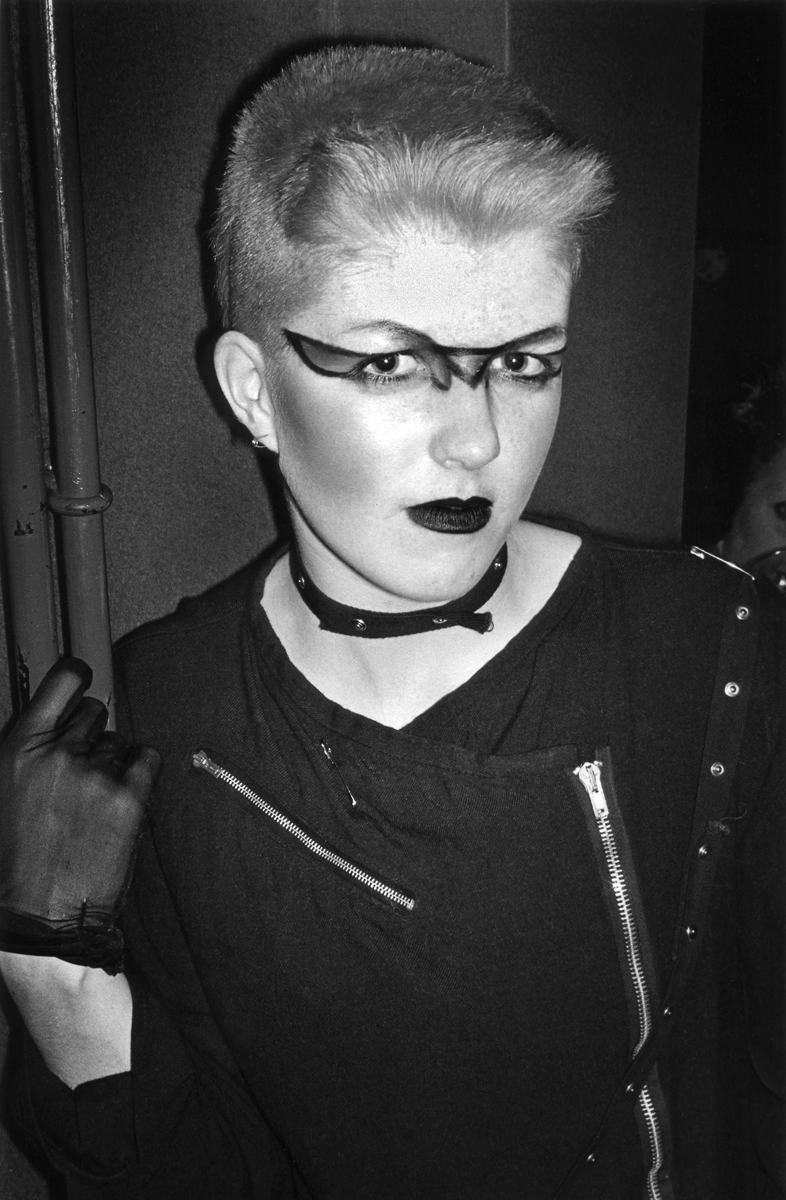

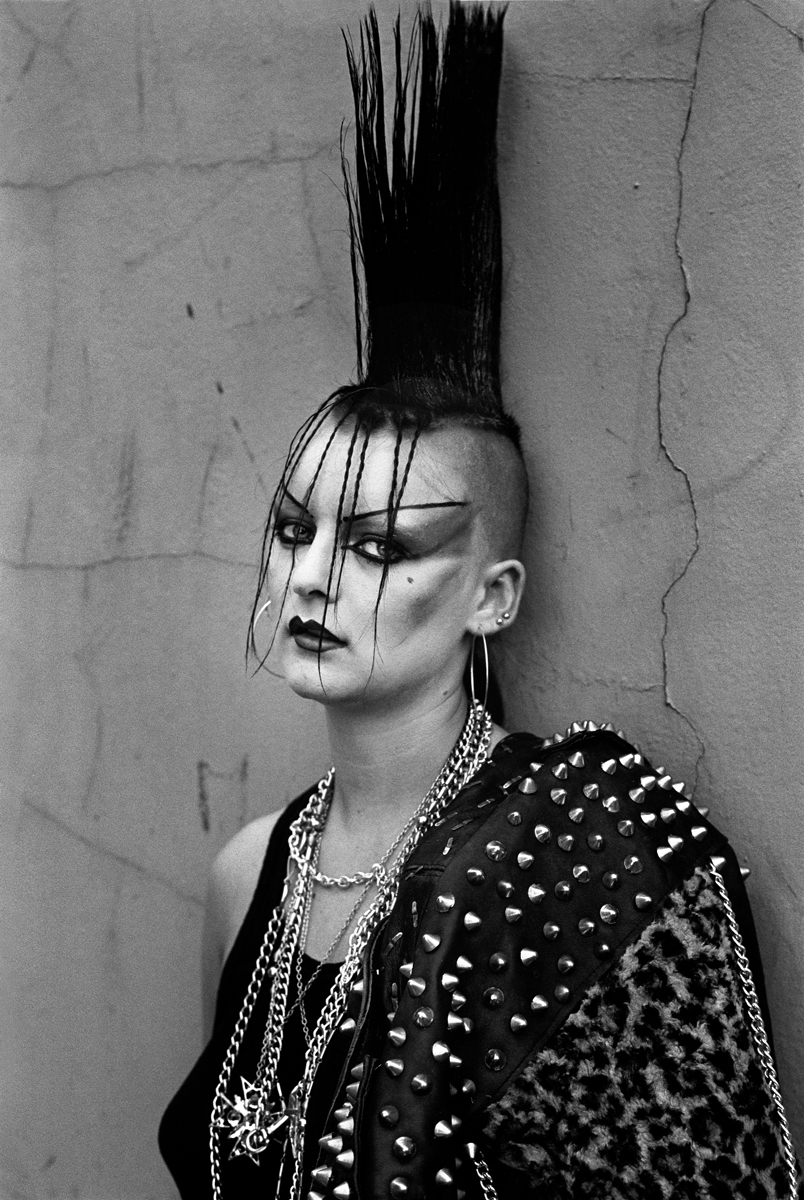

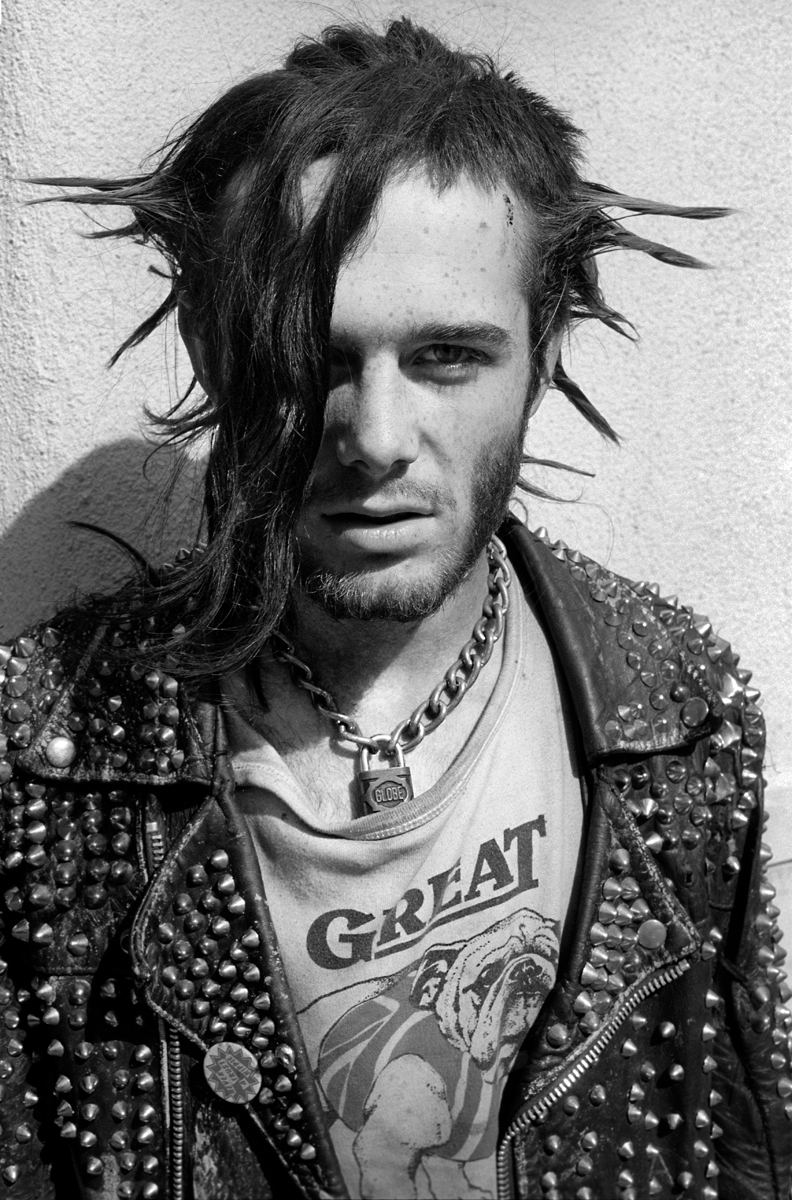

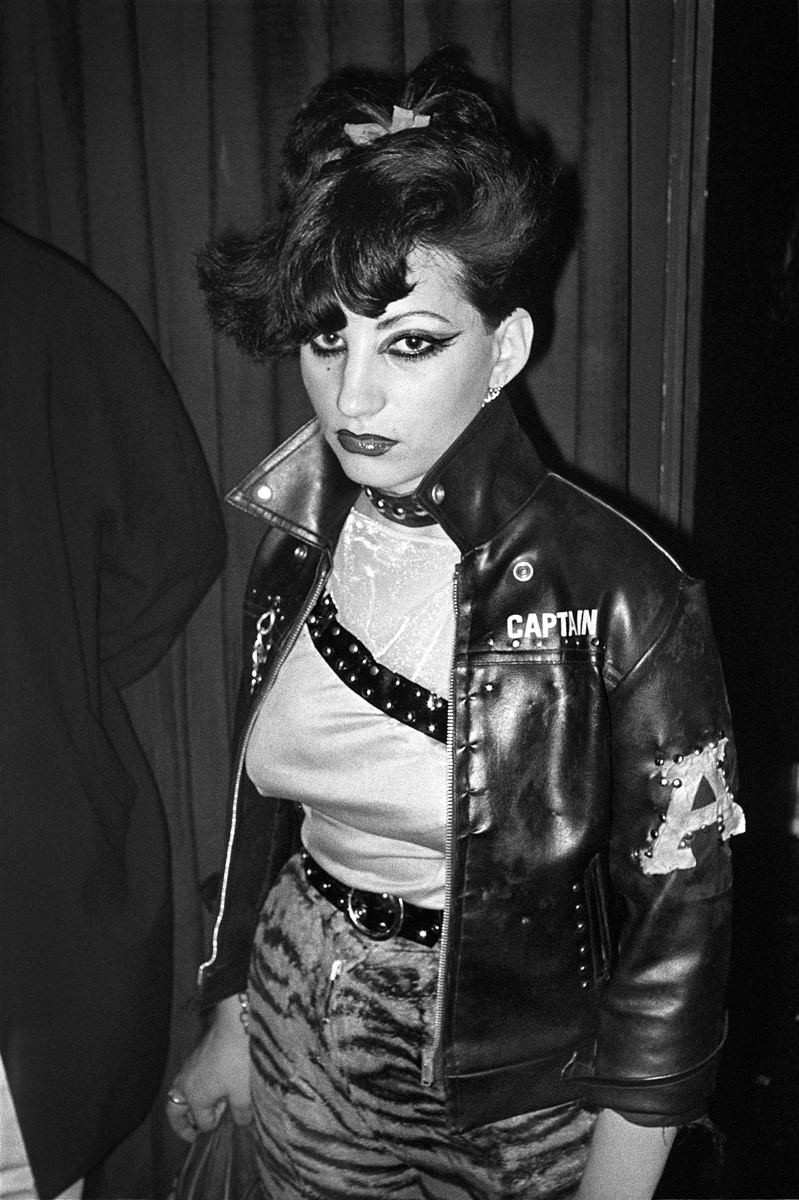

Some photographers’ most evocative images are shot while hanging out with their friends. Others, like Diane Arbus, are voyeurs looking at their subjects from the outside. Derek Ridgers never fell into either category – or any category, for that matter. He started shooting London’s underground youth subcultures during punk’s late-70s big bang, fascinated at the sight of spiky-haired teens slamming against the railings at his own first punk show. Though the ponytailed, cardigan-clad 20-something had long been a fixture at live gigs.

As an accidental insider, Ridgers was spellbound by this defining cultural explosion, and yet somewhat cynical of it. He might be the only punk-era icon still around who’s not nostalgic for pre-Thatcher nihilism – in fact he kinda loves the idea of “weekend punks” who slick up their office-appropriate bowlcuts for one night being soaked in spit and sweat. Well, as long as they don’t make him listen to their iTunes Most Played. As he shares some of his most iconic portraits, Ridgers tells i-D about his visceral connection with skinhead culture, his dad’s attitude to long hair, and where these crazy-haired kids are now.

You’ve talked about starting photography because you wanted to get closer to the bands. Do you remember the moment when you started becoming more interested in the mohawked kids than the music?

Yes. Actually, I remember the exact moment. It was the late autumn of 1976, during a set by the punk band The Vibrators at Kingston Poly in West London. I was right up against the stage and the rest of the crowd was right up against me. The band came on and immediately the crowd started to go completely wild, pogoing and jumping up and down on one another. Pulling crazy faces and rolling around on the floor.

By 1976, I’d been going to rock shows for ten years – Hendrix, Floyd, The Stones, The Doors etc – and never seen anything like that before. I was a little taken aback. But it was undoubtedly photogenic, I could see that straight away. I wanted to photograph the crowd more than the band but I didn’t, at that time, quite have the balls to do so. It took me a few weeks to work up the courage to try to shoot the punks.

You never really fell in with one particular subculture. Was being an outsider integral to your success as a photographer?

Looking back, I suppose it was, but it certainly didn’t occur to me at the time. I was an only child and I would have dearly loved to have been a part of something, anything, when I was younger. From around 1965 or 1966 I tried in succession to be a mod, a hippie, a skinhead and then back to a hippie again. But I was never much good at any of them. During that time, I was at school and then art school and living at home with my parents, and there were always pressures from my dad to have either shorter or longer hair – normally shorter.

All I was left with now was an admiration for soul and ska, a love of virtually anything to do with hippiedom and a visceral connection with skinhead culture – though certainly not the politics. I’m still very much a hippy in my head. I’ve had a ponytail forever and this will be the third decade since it was last in fashion. I’m old enough now that I don’t care. I may very well be the only one from the baby-boomer generation who is a mélange of all of the above subcultures.

Do you ever get nostalgic looking at your photographs from the dawn of punk?

No, not at all. To some extent punk only happened because of the rather depressing social climate of the time. A very right-wing Labour government, followed by the overt nastiness of Thatcherism. Unemployment, power cuts, the miners’ strike, the three-day week, IRA bombs and rubbish piled up high in many Central London tourist spots. How could one be nostalgic for that era? Of course, it’s even worse now. Far worse. But I still don’t look back at those times with any great affection.

Do you sympathize with people who get annoyed by today’s commodification of punk and appropriation of punk aesthetics?

No, not really. It didn’t ever really belong to them did it? And, even if it did, why can’t other people inherit that same spirit? Or revisit the zeitgeist and make it fit their own circumstances? Like Los Punks in East L.A. I reckon there will be some of those kids who have never even heard of the Sex Pistols, just as some young photographers have never heard of Richard Avedon or Irving Penn. And, in 2017, does that really matter if their lives are enhanced even a little bit by their own personal understanding of what punk means?

In my honest opinion, Malcolm McLaren, Vivienne Westwood, and the Sex Pistols didn’t invent punk, and neither did Richard Hell. They helped it to evolve is all. Just like the Dead and Airplane didn’t invent the Summer of Love. Everyone wants to take ownership of what formed them in their youth, of course they do. But so what if people work in a bank all week and gel their hair up on a Friday and become weekend punks? Who really cares and how does it affect me and my history? Good luck to them. Some of the weekend punks look wonderful, one can almost smell their shampoo from here. Just don’t make me do it myself and don’t make me listen to Psyk Ward or Las Cochinas.

Have you noticed a shift in the way young people approach dressing up and going out, since the advent of Instagram?

Yes, very much so. These days people still dress up, show off, and act outrageously, but they often don’t even have to leave their own bedroom to do it. Their public stage is now Instagram and Facebook. Back in the days of the original punks and New Romantics, people would dress up and go out on the bus. They’d often run the gauntlet of public derision and sometimes worse. Back in the day, London could be quite a violent place, and it still is, in some places.

Someone like Leigh Bowery could come out of his North London flat virtually naked, save for a bit of body paint and a few twigs, and he’d travel to all the clubs on a bus. He was a big bloke but that still takes some cojones. And the clubs from those days were mostly dingy, dark, dirty little basements which were so wall-to-wall packed that you couldn’t even move around. Some were so loud you couldn’t hear yourself think let alone communicate with the person stood next to you. And yet, people still did it. They went out every night and they loved it. And they’d still do it today, if they could. Except so few of those kind of clubs exist now.

What do you find exciting as a photographer today?

Everything. Every single thing. You simply can’t be any good as a photographer if you become jaded. I shoot a lot less these days but I’m far more enthusiastic than I ever was in the punk era because these days, I recognise the transformative effect photographs can have. Working for The Face in 1980 completely changed my life.

I simply wasn’t interested in being a photographer when I was young myself – despite being totally entranced by the film Blow-Up and its momentary flash of female pubic hair. Back then I wanted to be a painter, or a famous art director, and a big part of me still does. I love all the visual arts with a passion, even typography. But, as I said, photography changed my life and it continues to do so to this day. Photography has given me a fabulous life but I promise you, I haven’t taken it for granted. Not for a moment.

You’ve actually made contact with a few of the crazy-haired kids you shot all those years ago. Are you ever surprised by how much they’ve changed or remained the same?

Both. Shocked is a better word than surprised. I’ve been most shocked by two things: One, How many of them didn’t make it. This is especially true of the young men I photographed. Tuinol Barry for one. He took the life and eventually the life took him. It’s great that he’s remembered but it’s such a terrible shame that they all aren’t. Two, I was utterly gobsmacked by how little some of the original female punks and new romantics had aged. A few of those I met 40-odd years ago look to have aged by about 10 years. Sometimes not even that. Princess Julia, for instance, looks as beautiful and sexy as she did 40 years ago. What kind of weird magic is that? It would be cruel to name any of the others because I’d inevitably be leaving some of them out. Many are on Facebook though, so you can see for yourself.

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

Photography Derek Ridgers