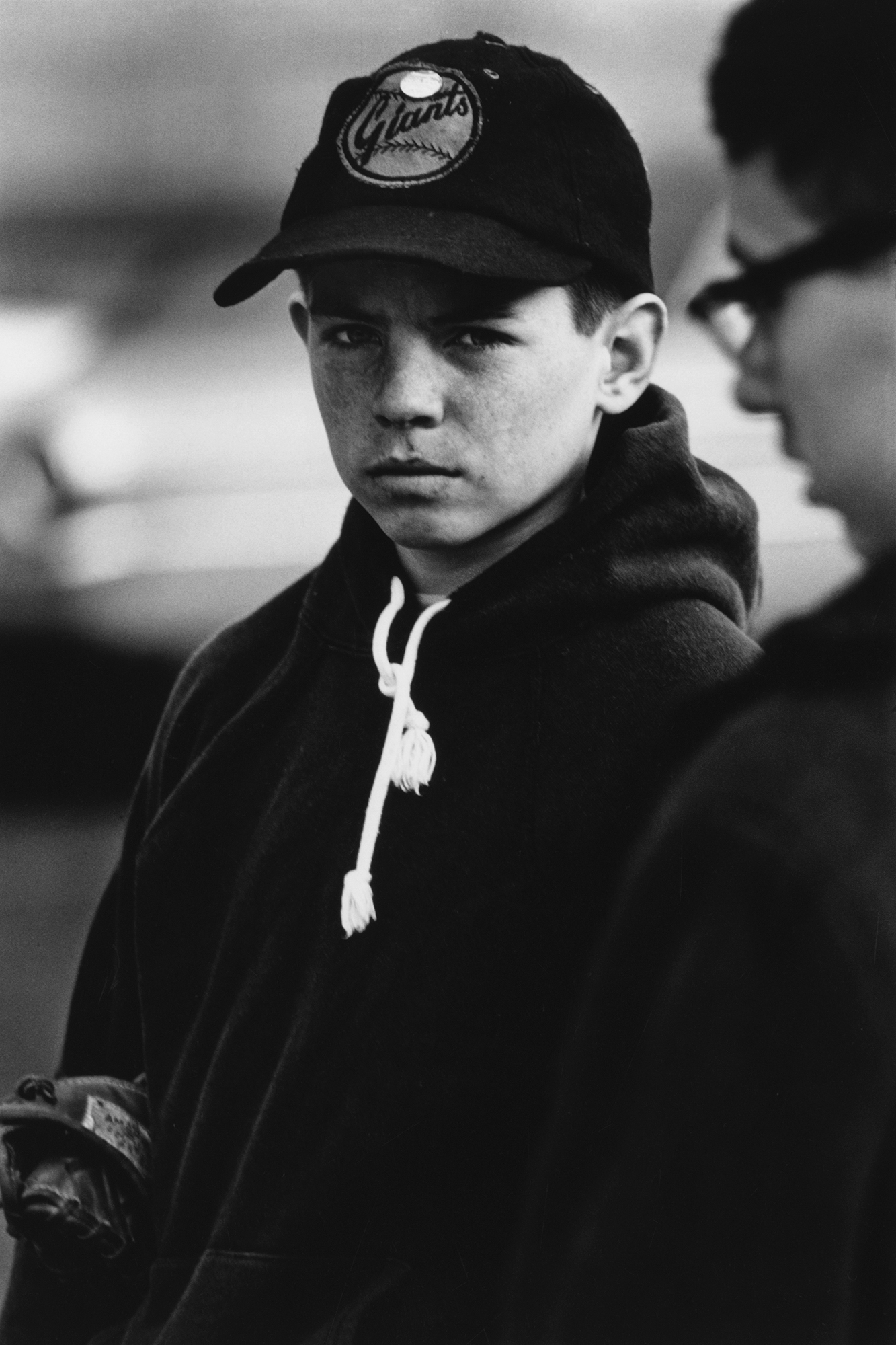

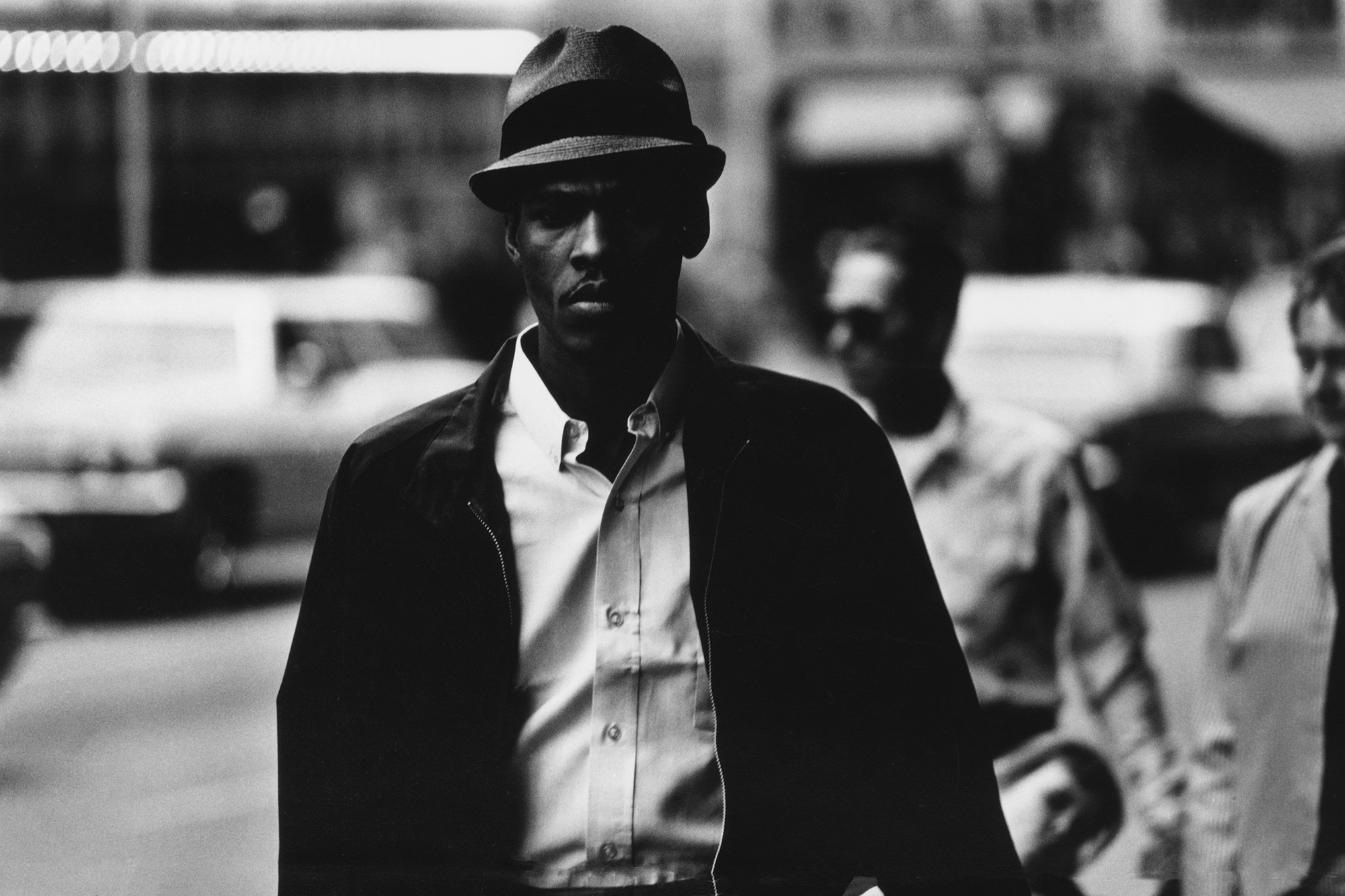

In Dave Heath’s seminal book, A Dialogue With Solitude, the photographer captures a post-war America at the beginning of a cultural and economic boom, on the cusp, and then amid a major civil rights movement. However, these things are rarely at the forefront of the work, instead quietly contemplated as background noise. Largely shot in North American cities like Chicago and New York, where Dave lived in the mid-50s after returning from the war in Korea (portraits of his fellow servicemen also feature, interspersed with scenes from the street), the book is a visual anthology that recognises the more introspective moments of everyday urban life.

Published in 1965 following successive Guggenheim fellowships in 63 and 64, the series arrived seven years after Robert Frank’s The Americans, considered by many to be one of the most influential photobooks of the 20th century (despite initial criticism on its US release). Confronting similar topics like class, comparisons between the two were almost inevitable, with many perceiving Dialogue as the lesser work. “That hurt, stung him pretty bad,” says gallerist Stephen Bulger, a former student of the late photographer. It quickly went out of print but was reissued in 2000 with the addition of a letter from Robert (the two were friends), and later informed the exhibition Multitude, Solitude: The Photographs of Dave Heath, which opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2015, nine months before Dave died on his 85th birthday in 2016.

“He was very cogent,” continues Stephen, who studied at Toronto Metropolitan University (then Ryerson Polytechnical Institute) between 1986-91, and today represents the photographer in Canada. “He was short with words, but every word that left his mouth was very important; you just had to listen for it. [At the university], he was known as the studio critique guru; his class was essentially a one-on-one critique of whatever work you were making at the time, with little handholding.” While Dave continued to teach at Ryerson until 1997, it had an adverse effect on his own practice, and he moved away from printing his images, instead working with slide shows and appropriating the work of others. After he left, he returned to the street and produced a series of digital colour pictures, publishing Dave Heath’s Art Show in 2007.

One Brief Moment, a new monograph published by Stanley/Barker, builds on the ideas of Dialogue, similarly informed by the photographer’s early life and the ongoing sense of isolation he carried. Born in 1931, Dave was abandoned by his parents as a young child and spent many years in orphanages and foster homes in Philadelphia. He arrived at photography in his teens through the spreads of Life magazine — and W. Eugene Smith in particular — and found a way to illustrate his experiences. “He was interested in documenting, sort of, his condition; it was a very personal statement,” Stephen says, referring to Dialogue but ultimately describing Dave’s oeuvre as a whole. “It was meant to touch on the universal, but really dealing with this angst that he had about being isolated in the world.”

A singular approach to storytelling continued throughout Dave’s career, as Stephen notes, “He wasn’t interested in the individual photograph; he would talk about sequencing as like writing prose. You want it to have commas and spaces because if a paragraph is filled with exclamation marks, the power of a big exclamation mark is diluted. He was very much using photographs as a language that was trying to tell a story or, at least, a sentence about something.”

Further documenting city life in New York and Chicago, but also in Missouri, Ohio and Kansas, One Brief Moment sees 72 of Dave’s photographs, from 1965 through to 67, brought together for the first time. Often tightly cropped, the photographs instead lean into his subjects’ emotions, curating a survey of expressions and interactions between people on the sidewalk. “Each picture is so packed with information,” Stephen says, “they’re great representations of the people on the street, most of whom had no idea they were being photographed. You can really scrutinise all of their interactions and the clarity of character that comes through.”

The new book closes with a quote by Dave from 1974, in which he assesses the motivation for his work as almost a balm for a previous episode at 25 when he tore up photographs of himself, his mother, father and foster family. “I wanted to purify myself, to clean the background out of my system,” he says. “And I think now that I shouldn’t have done that, because I’ve collected all these old photographs to replace those five. So in a sense, those five have generated themselves into thousands. In a way, it’s like trying to recreate, through these old photographs, a family album of my own for a family I never had.”

The account is sympathetic to the way he created work throughout his life, which Stephen suggests was about immortalising something bigger than himself. “He wasn’t trying to make one great picture,” he says, “he was trying to make a stream of really good pictures that amounted to something.”

Credits