Until 1993, there stood a structure in Hong Kong like no other. On a small plot of land in Kowloon, a mass of buildings stretched skywards, interconnecting like a jungle canopy to form a single dense block. Reaching 14 storeys, its facade glowed with the fluorescent lights of hundreds of tiny apartments and shops. Packed inside were schools, workplaces, medical clinics, and factories; places of worship, relaxation, and hedonism – and more than 35,000 inhabitants living on top of one another.

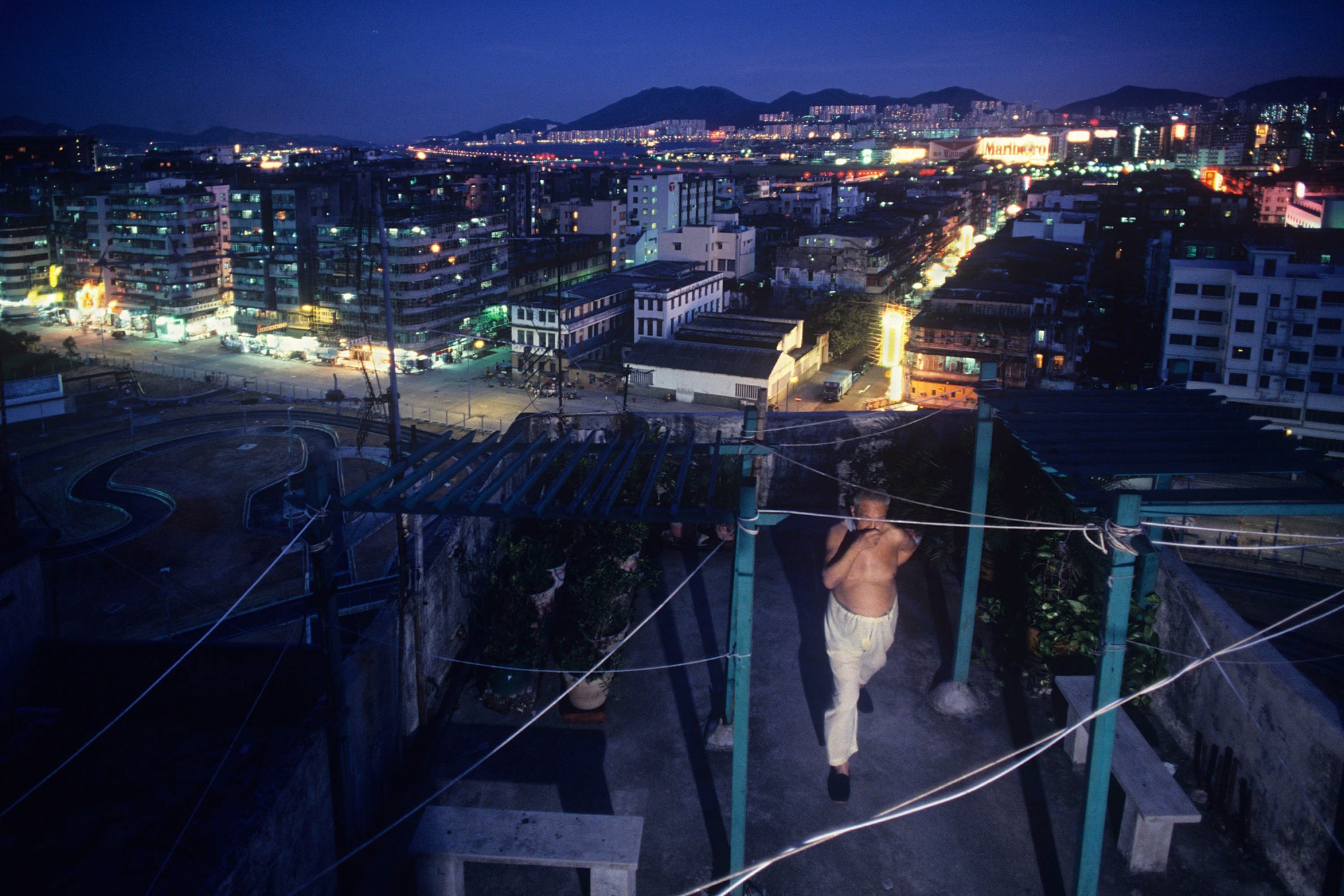

This was the Kowloon Walled City, a Chinese squatter settlement in the middle of British-ruled Hong Kong. A self-governed city within a city — which grew organically like a living creature, without the input of architects or engineers, without law, authority, or regulation — it was, at its peak, the most densely populated place on earth.

Vancouver-born photographer Greg Girard heard about the Walled City after moving to Hong Kong in his late 20s in 1982. As was typical at the time, its sordid reputation preceded it. Originally a Chinese military fort dating to the Song Dynasty (960–1279), the Walled City became an enclave of Chinese Sovereignty when the New Territories — one of Hong Kong’s three main regions and by far its largest — were leased to the British in 1898. Neglected by Mainland China and cautiously left alone by the colonial government of Hong Kong, an institutional vacuum opened up, and the city became infamous as a symbol of lawlessness and crime, heaving with gamblers, opium dens, brothels, and Triad activity. While its physical walls were demolished during WWII, its symbolic boundaries remained.

One night in 1985, while photographing the streets around the now-defunct Kai Tak Airport, Greg Girard stumbled across it. “I turned a corner and there it was: this huge, Medieval-looking thing at the end of the block. It looked like it had sampled the neighbourhood and turned into a kind of Frankenstein agglomeration of buildings,” he says. “It was just extraordinary because it so clearly broke every construction regulation there was. That’s when I realised it must be the thing I’d heard about, the Kowloon Walled City.”

Stepping inside, the photographer was swallowed up by a labyrinth of narrow alleys that dipped and twisted. Dingy green lighting illuminated an impossible tangle of tubing and wires overhead, while soaking refuse dripped down from upper floors, and sewage ran in the gutters underfoot. Chemical odours from plastic factories merged with the stench of raw and barbecued meat from pork and fish ball factories. Radios and televisions blared, and Mahjong tiles clattered. “It was a sensory overload,” Greg remembers. “It felt otherworldly, and yet totally normal to everyone living and working there.”

He didn’t photograph the enclave that first night, but continued to visit, little by little, getting to know its residents, many of them from Guangdong Province in south of Mainland China, and the fluid way it functioned. From 1987, the year the Hong Kong government announced the City would be cleared and its residents resettled, until 1992, he documented it in detail alongside architect and fellow photographer Ian Lambot, assisted by historian Emmy Lung. Full of photographs, interviews, maps and essays, Greg and Ian’s books City of Darkness – Life In Kowloon City (1993) and City of Darkness Revisited (2014) remain the most thorough record of daily life within — the title drawn from the Cantonese name for the City: Hak Nam.

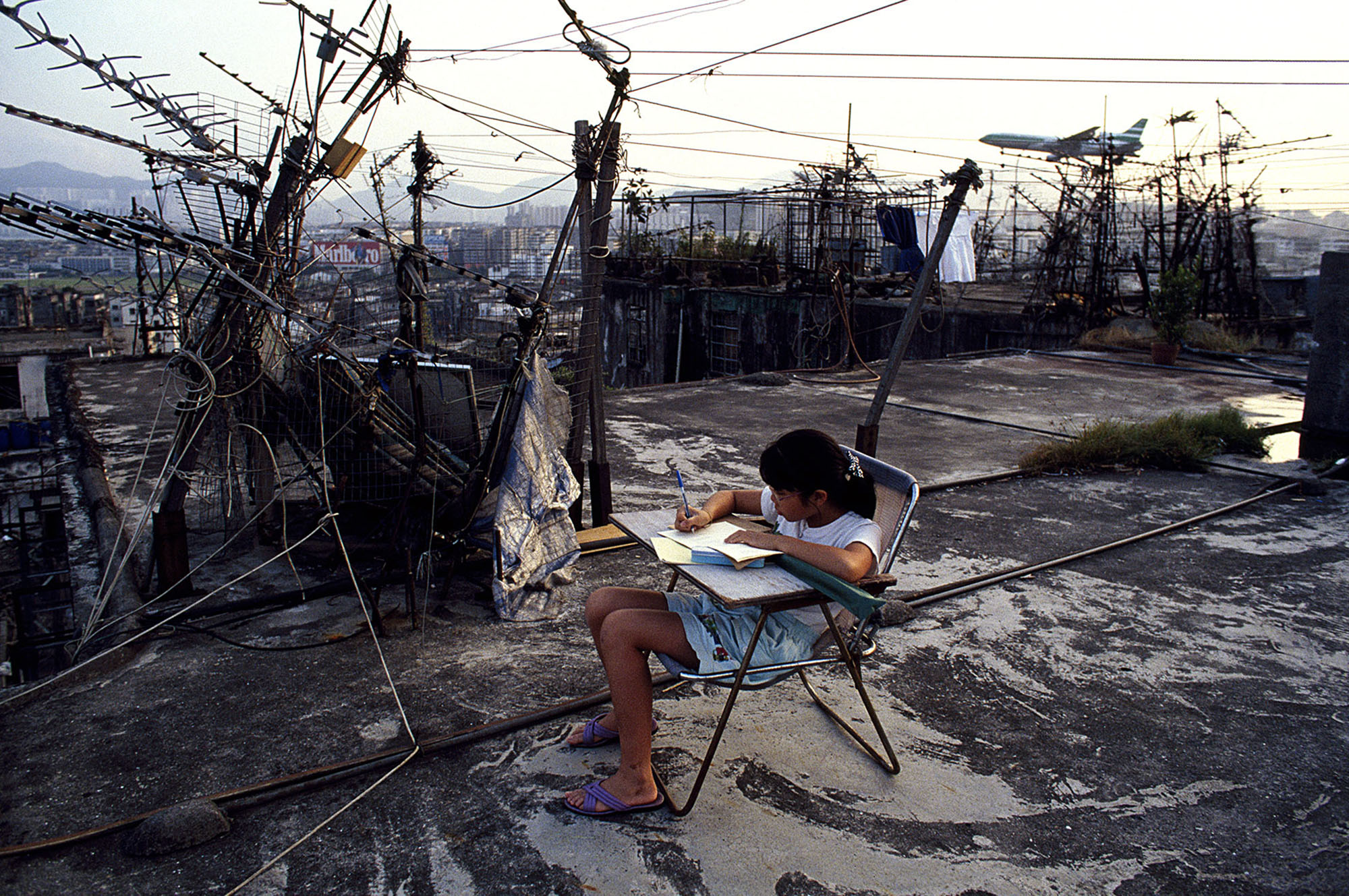

“The Walled City had this reputation for drug use, violence, gambling, prostitution. But by the 80s at least, if you spent any time there, you quickly understood that this was a place where people were trying to raise their kids, make a living and get by. It was like any working-class neighbourhood of Hong Kong, except this one was just physically so extreme. Our initial impulse was to show what it was actually like, since its reputation was so out of kilter with its reality by that point.”

Although the locals were wary at first, Greg gradually earned their trust. “I kind of intuited that the more gear you’re carrying, the more serious you look, and that would serve you better than trying to surreptitiously take pictures,” he says. “I decided early on to make the kind of pictures I was making for magazines like Fortune and TIME — if you’re photographing a celebrity or a business person, you light them properly. So I used a lot of lighting to really show what the place looked like, and photographed in colour rather than black-and-white. I didn’t want to romanticise it.”

Focusing on the rhythms of the “village-like” community within, the photographer captured workaday scenes of the postmen who expertly navigated the disorienting maze of passageways, the City’s countless unlicensed dentists, and butchers stripped down to their underwear in the heat and humidity, smoking cigarettes as they tended to pig carcasses splayed out on the floor. Contrasting with the dank depths of the place are shots of children playing on the roof among television aerials, discarded furniture, and washing lines, overlooked by their grandmothers and the jumbo jets that practically skimmed the City as they descended into Kai Tak Airport.

Immortalised in these images, the City’s rich visual vocabulary of shadowy alleys, jumbled signage and intersecting rooftops proved irresistible to graphic artists and designers worldwide. Since its demolition in 1993, it’s been sampled endlessly, inspiring the Narrows in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins (2005), setting the scene for video games like Call of Duty: Black Ops, and featuring in cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson’s novel, Idoru (1996). It sparked Manga series, theme parks, and even the name of a San Francisco sludge metal band who’d never stepped foot in Hong Kong.

“Its cultural influence was something we couldn’t have predicted at the time,” Greg says. “We wanted to present a fair portrait of the City and its close-knit residents, who made the best of an extremely challenging physical situation, and it became a kind of springboard for people to take it to the next level.” Beyond its romanticisation as a neon-lit, urban dystopia, he believes the City captures imaginations as a space that “exists outside the rules, where anything can happen.”

Today, a park covers the site where the Walled City once stood. Greg’s images, and the creative re-workings they informed, serve as a form of cultural preservation. “It’s ironic, isn’t it, that it often takes something to disappear for it to be appreciated. Had the Walled City lasted just a few years longer, I think a whole generation of young Hong Kong people would be all over it, filming it, photographing it, arguing for it to be saved or commemorated much better than it was.”

You can see more of Greg Girard’s work on his website and Instagram. His book, ‘Kowloon Walled City: Revisited’ is available to buy here.

Credits

All images courtesy of Greg Girard