Self-taught photographer Daniil Kotliar was born in a small town on the outskirts of Nikopol, an industrial city in south-central Ukraine, in 1999. Nestled on the right bank of the Dnieper River, “Nikopol is where everyone from my village would be commuting for work”, he explains. “Working in its factories was one of the few things people could do for a living as we didn’t have much there.” Having grown up as the youngest son in a family with many sisters and brothers, raised by a widowed mother, Daniil describes his upbringing as anything but easy. “Let’s put it this way,” the image-maker says, “my town and childhood embodied the kind of reality people would want to turn around not to see”. In spite of the difficulties, his home granted him many of the memories he carries with him and regularly reminisces about today. Of all of them, it’s Malanka, Ukraine’s Orthodox New Year celebration, that Daniil remembers most vividly – so clearly he dedicated his debut monograph to it, 13th January.

Also known as “Old New Year”, or Shchedryi Vechir in romanised Ukrainian, this folk holiday corresponds to the New Year’s Eve of the Gregorian calendar. Taking place through the night of 13 January, Malanka draws on a Christianised popular tale of pagan origin chronicling the sudden disappearance of Spring-May, daughter of Praboh – the god of family, ancestors and fate in the pre-Christian, Eastern and Southern Slavic religion. As the story goes, the goddess, who was later renamed “Mylanka” from the Ukrainian word for loving, had been forced into the underworld by her evil uncle, the Devil, causing the Earth to lose its seasonal bloom. Upon her long-awaited return, which signifies the onset of spring – when the pagan celebration previously took place – the world’s greenery was restored as were people’s spirits. In modern Ukraine, this century-long tradition is reinvigorated by local communities spread across the country, each one readapting it through the filter of their own subculture. In Daniil’s case, Malanka manifested itself as a joyful break from the gloominess of ordinary life: on its eve, he would knock on each and every door in his village, throwing sweets at the lucky hosts in exchange for coins, food or more treats.

“Every time someone opened their door, I would sing a song and drop some candies on the floor, secretly hoping to get something in return,” the photographer laughs. “I would spend the whole night as well as the following morning wandering the streets on my own: everyone in my town knew me, so it was safe enough for me to be by myself.” Aware he could make some money out of it, his mother would let him skip a day of school to participate in the folklore, “which made everything even more exciting”, Daniil says. While this annual ritual had accompanied him throughout his childhood and teenage years, it wasn’t until he turned 18 that the image-maker stumbled across the Malanka iteration now serving as the subject of his first photo book. “At some point, a couple of friends showed me how the Old New Year feast was celebrated in south-west Ukraine, close to the Romanian border,” he recalls. “Set in the Bukovina region, this version of the tradition felt even more mysterious, surreal and stuck-in-time.”

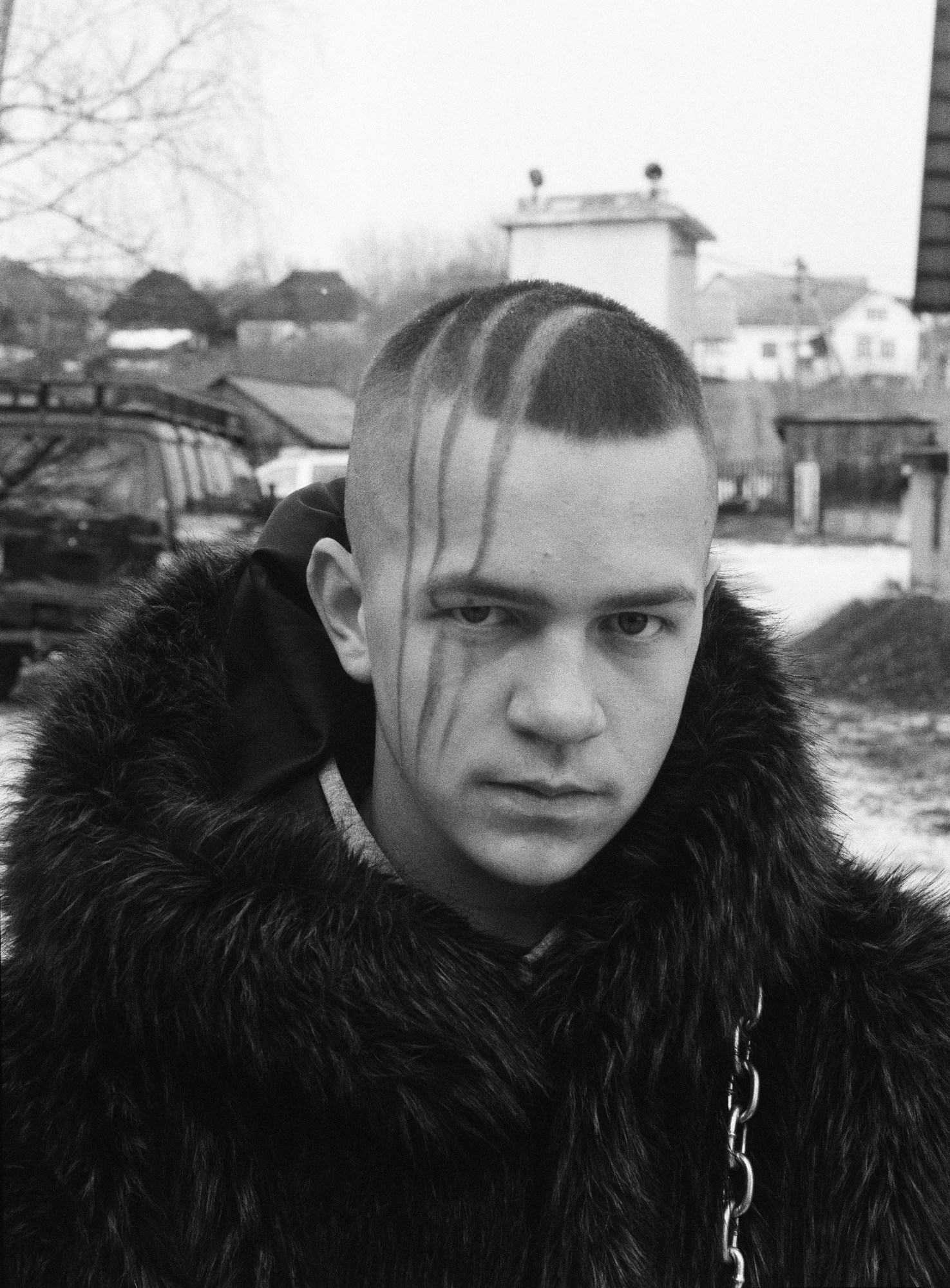

Published by AYVAN, an independent design and publishing platform based between London and Paris, 13th January puts the protagonists of the festivity into focus. Shot on black-and-white, grainy film loaded on both a Mamiya M645 and a 35-mm point-and-shoot camera, the photographs garnered in the volume document the intergenerational swathe of people coming together to celebrate the return of the good season. Captured against the rural backdrop of a Ukrainian village, the children, teenagers and elderly people filling the pages of Daniil’s book appear masqueraded in handmade costumes – including spooky creatures, demons, bears and St. Basil-inspired ones – or else adorned in meticulously crafted, beautiful uniforms and beaded headdresses. Reviving the town as they parade across it in their colourful disguises, the participants of the Malanka carnival stand as a symbol of their long-lasting connection to their local heritage, mythologies and roots. Of all the masks at the heart of the tradition, it is Spring itself that takes centre stage: unveiling itself to the public through a young girl wearing a silver star on her forehead; her youth, candour and spiritedness reminding everyone of how even the darkest of days give way to a new dawn.

While the melding of pagan and Christian festivities has made decoding the numerous historical references, symbolism and narratives converging into Malanka a laborious task, for Daniil, the ritual carries a universal message. “13th September is my attempt at immortalising the two sides of the human condition: the good and the evil, light and shadow, joy and loss, birth and death,” he says. And if the resurfacing of spring corresponds to a new beginning, “the children’s energy pulsating throughout the book is the closest thing I know to the resilience needed to outdo a cold winter”. Speaking on the reasons that brought him to develop this project, Daniil explains that the series came as a reaction to “commercial” visual depictions of the Old New Year rite. “I had dreamt of attending this pageant for years when, one day, I came across another photographer’s documentation of it,” he recalls. “It felt as if it lacked substance, as if those images were meant to sell the feast’s atmosphere to people coming from abroad without actually scraping beneath the surface.” Knowing that there was more to its story, Daniil promised himself that he would be narrating it through his own lens the following year.

Developed in January 2021 – only a year and a month before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – with its dense monochromatic palette, 13th January takes the Malanka celebration out of its framework of reference, restituting a transcendent, evergreen homage to Ukrainian culture. “From the very beginning, I wanted the project to be black-and-white, so that the images could feel atemporal and, therefore, eternal,” Daniil explains. “Using colour would have instantly given away the moment in time when the series was made: instead, I chose to let these photographs simply exist.” Intent on doing justice to Ukraine’s older generations, those who “keep the tradition alive”, while also spotlighting younger Ukrainians’ willingness to take it on their shoulders, the image-maker juxtaposed portraits of the two “faces” of the country in a visual dialogue between its past, present and future. “As Bukovina is so close to Romania, most of its youth will likely leave Ukraine to study abroad, either there or in another one of the nearby countries,” Daniil says. “My goal was to ‘freeze’ them right where they were as they welcomed the most mystical time of the year alongside their loved ones.”

If at first, working on this project allowed Daniil to fully embrace the otherworldly feel of his favourite Ukrainian holiday, finding himself in the south-west portion of the country soon opened up his eyes to the intricacies of its cultural spectrum. “Although 13th January was put together in Ukraine, visiting Bukovina for the first time made me aware of the infinite shades that compose our vibrant heritage and identity,” he says. “It is a crossroads of cultures, where the Ukrainian and Romanian ways of life constantly spill and merge into each other – a whole new world I didn’t know.” With the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in February 2022, the monograph instantly acquired a new meaning. A love letter to Ukraine and the resilience of its people, 13th January stands a proof of existence of the country’s manifold legacy: a tight-knit, community-specific melting pot of rituals that, in spite of the ongoing threats, can no longer be ignored or suppressed. Yet, as attested by the success of its recent launch and collateral exhibition at Paris’ Sheriff Gallery, the volume’s resonance moves well beyond Ukrainian territory.

“What I loved most about the making of this book was seeing people from all sorts of backgrounds recognise a part of themselves in its story,” Daniil says. “I had random passersby stop at the gallery just to tell me that, even in their own country, they had traditions similar to Malanka, which proves that, after all, what unites us is more than what sets us apart.” As he searched for words to describe what he hopes the book will evoke in those flipping through its pages, the photographer’s choice naturally fell on “empathy” – an emotion that, since the development of his very first series, Read the Faces, has come to define the direction of his entire visual experimentation.

“I started out by photographing people on the streets in and around my hometown,” he says of the protagonists of his debut project. “I was always drawn to subjects that had something to say, strangers who felt weirdly familiar – maybe because of everything we had both gone through, or perhaps because of how they carried themselves.” It was while shooting that story that Daniil understood that “empathy isn’t something we have from the very beginning”, but a gift that needs to be nurtured continually in order for us to be able to connect with other people.

“Photography is my way of making others feel the same way I feel, my attempt at finding some common ground we can both stand on,” he explains. “All I wanted with 13th January was to give people the opportunity to live some of their most precious memories once again as if it was the first time. To show the importance of culture and why it will always be a fundamental part of our lives.”

Credits

Photography Daniil Kotliar