When American visual artist Anne Collier began appropriating imagery and reimagining the ways in which we communicate through photography, social media wasn’t even a glimmer in a young Mark Zuckerberg’s eye. Over the course of her career, the landscape of image creating, sharing and manipulating has fundamentally changed. Search the hashtag “obsessed” on Instagram and you’ll find around 10,000,000 images. Search the hashtag “selfie”, and you’ll be presented with almost 355,000,000. Most of these images have been accrued over the last six years, but the origins of our paroxysmal compulsion to post and repost images of ourselves, others and the products we covet, lies firmly in Anne’s revolutionary body of work.

Studying under some of 20th century America’s most evocative, insurgent visual artists — Mary Kelly, John Baldessari, Paul McCarthy — at the California Institute of the Arts and UCLA, Anne has developed a unique and genre-blurring style of image-appropriation. Her projects examine the frontier on which we understand ourselves and our place in the public domain, as well as the cult of celebrity, the human condition our complicated relationship with culture and capitalism.

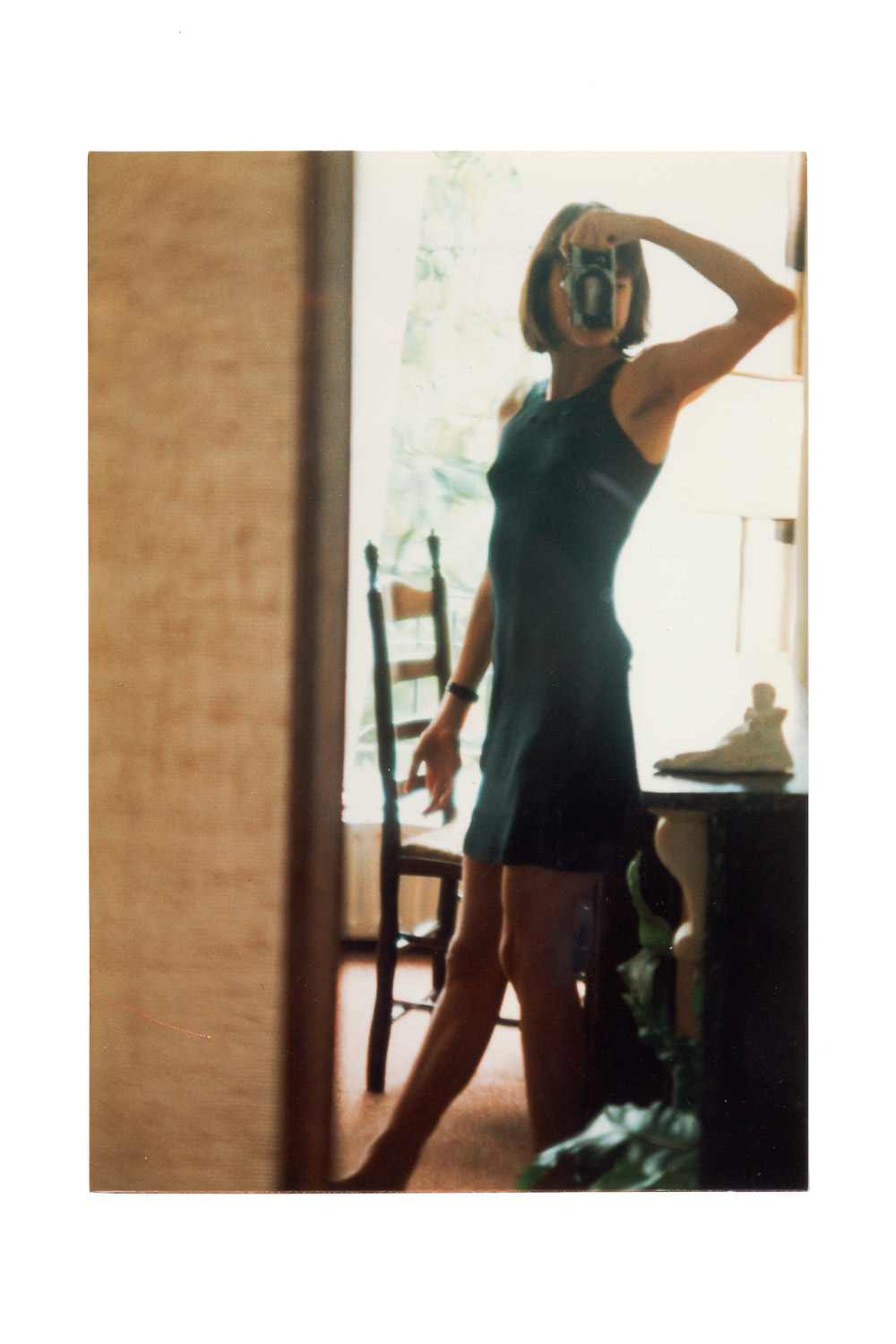

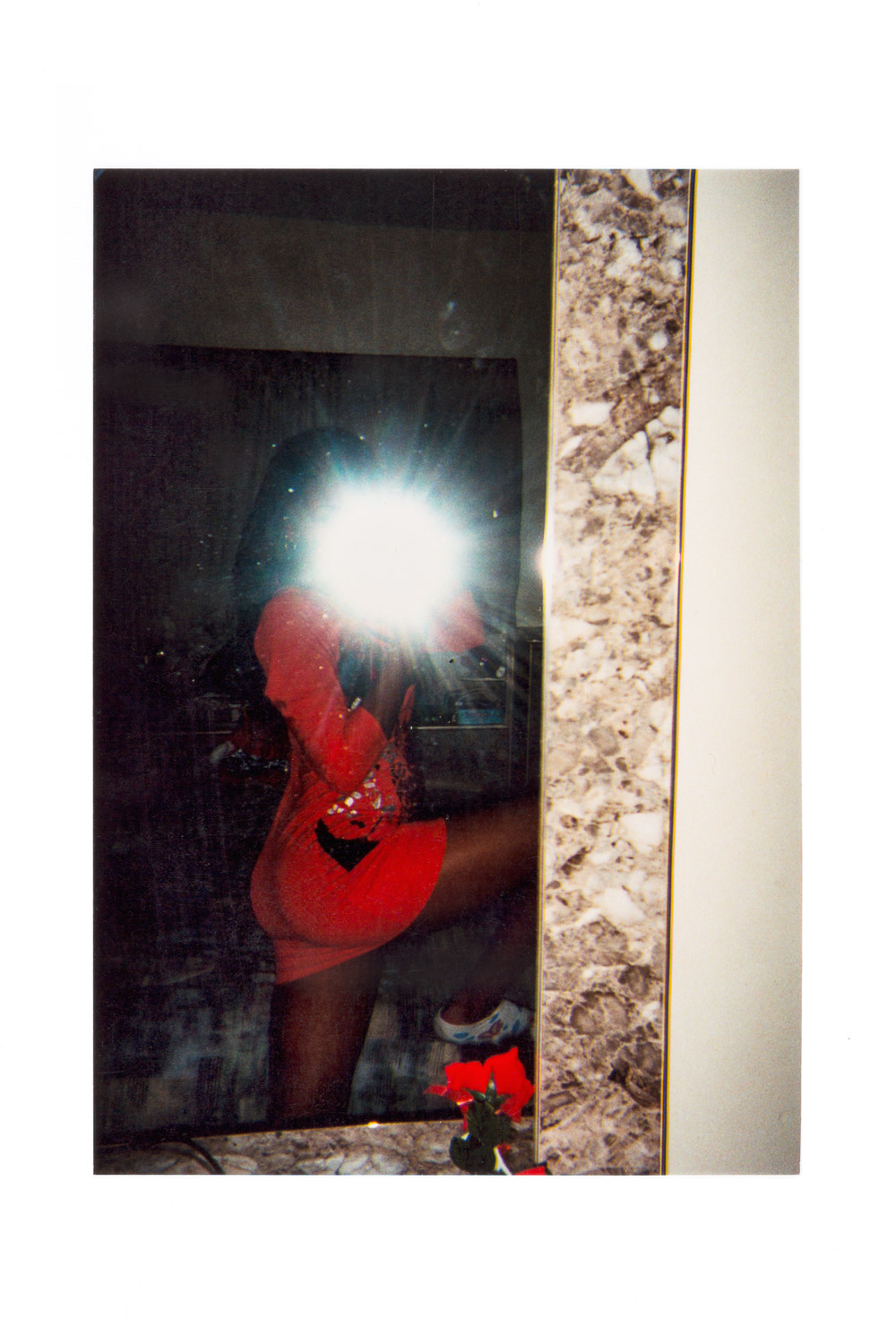

Her latest series of work, Women with Cameras (Self Portrait), compiles 80 found self-portraits taken by different anonymous women between the 70s and the early 00s. From car mirrors to public bathrooms, faces often remain shielded by the camera itself — the front-facing camera many years away — yet the style and atmosphere of each image tells a unique and varied story of each woman. Collecting the images from far and wide — thrift stores, markets, online — Anne soon became interested in the idea that these private images were essentially abandoned by their taker. The result is an engrossing study of our developing relationship with the lens. Here, we spoke to Anne about what she learnt from four decades of self-portraits.

Can you tell us a bit about where you grew up?

All over. I was born in Los Angeles in 1970, but my dad was in the navy, so we moved almost every year. San Diego, Sonoma, San Francisco, Memphis, Charleston, Indianapolis, Washington DC, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Panama…

How and when did you get into photography?

I got my first camera in sixth grade but my earliest relationship with photography was through images that appeared on record sleeves, posters, in magazines, and also in my family’s photo album. These vernacular manifestations of photography remain important markers for my own work.

Do you remember the first time a photographer’s work had a profound effect upon you?

Cindy Sherman. I saw her work when I was in high school, around the age of 17 or 18. Even without understanding the larger context (or history) of her practice it encouraged me to start thinking about myself in relationship to photography. Also at the same time I discovered Lucas Samaras, John Baldessari and William Wegman.

Did you study photography at university? Do you think artists and image-makers should study the craft at university?

I went to CalArts as an undergraduate, where I studied art — not specifically photography. I made photographs but also video works. I worked with some amazing people there including Michael Asher, James Benning, Al Ruppersberg, Morgan Fisher and the art historian Layne Relyea. Later I went to UCLA as a graduate student where I was in the photography department, which at the time was run by James Welling, but my other professors at UCLA included Charles Ray, Mary Kelly, John Baldessari and Paul McCarthy. My time at art school was an amazing education.

What makes a compelling, emotive image?

Something that resonates with your own inner experience combined with the outside world. It could be anything.

Do you think the emergence of the front-facing camera has enhanced and devalued our relationship with self-portraiture? Can you tell a bit about the story behind this project?

People have always made images of themselves. The images in my slide-show and book Women with Cameras (Self Portrait) all date from the pre-digital, pre-selfie era of photography. They represent the fundamental impulse to document ourselves, to record our existence. I started collecting amateur photographs of women taking pictures of themselves — self-portraits — about ten years ago, probably around the time that cellphone cameras were becoming more widespread.

The photographs I collected were mostly from the 70s to the early 00s. I would find them in thrift stores, at flea markets, and on online sites such as eBay. I was interested in how these ostensibly private images had entered into the public domain. I was interested in the fact that these images had been effectively abandoned by their original subjects — who were also the photographers. This idea of abandoned images is a recurring thread in my work, one that relates to photography’s relationship with memory, melancholia and loss.

Is there one image that means most to you?

Mirrors play an important role in almost every image. In some cases the presence of the mirror is evident, in others less so. You aren’t always aware of them. I like the idea of the subject positioning themselves in front of a mirror and then making decisions about how to pose, what to include in the image, what to leave out, when to press the shutter — the same decisions that all photographers make. The photographs have an uncanny sameness about them, even though they depict very different people, in different contexts, and at very different stages in their lives. There is an almost universal quality to the images.

What can we learn from four decades of women’s self-portraits?

The reasons why we might make images of ourselves probably haven’t changed that much over the past 40 years. What has changed is the technology that allows us to immediately share these images — through social media — with potentially anyone. This is the biggest difference. The analog images in my work were probably only originally seen by a very small number of people — the photographer, and maybe her friends and family. Whereas now, what was once private has, in many ways, become public. Women with Cameras (Self Portrait) is ultimately interested in this threshold — between the private and the public domain — and what role photography might play in such a conversation.

Purchase the book of ‘Women with Cameras (Self Portrait)’ here.