Matthew Brookes has photographed a lot of alluring celebrities: Chris Hemsworth, Robert Pattison, Jake Gyllenhaal and Ryan Reynolds. The photographer — who has also done campaigns for Boss and Armani, and international covers for Vogue, GQ, and VMan — recently explored the world of surfing, capturing roaming spirits and sun-kissed silhouettes in his new book, published by Damiani, Into the Wild. The book’s proceeds will funnel back into the Venice Beach community: namely Safe Place for Youth, a charity which helps homeless kids get back on their feet.

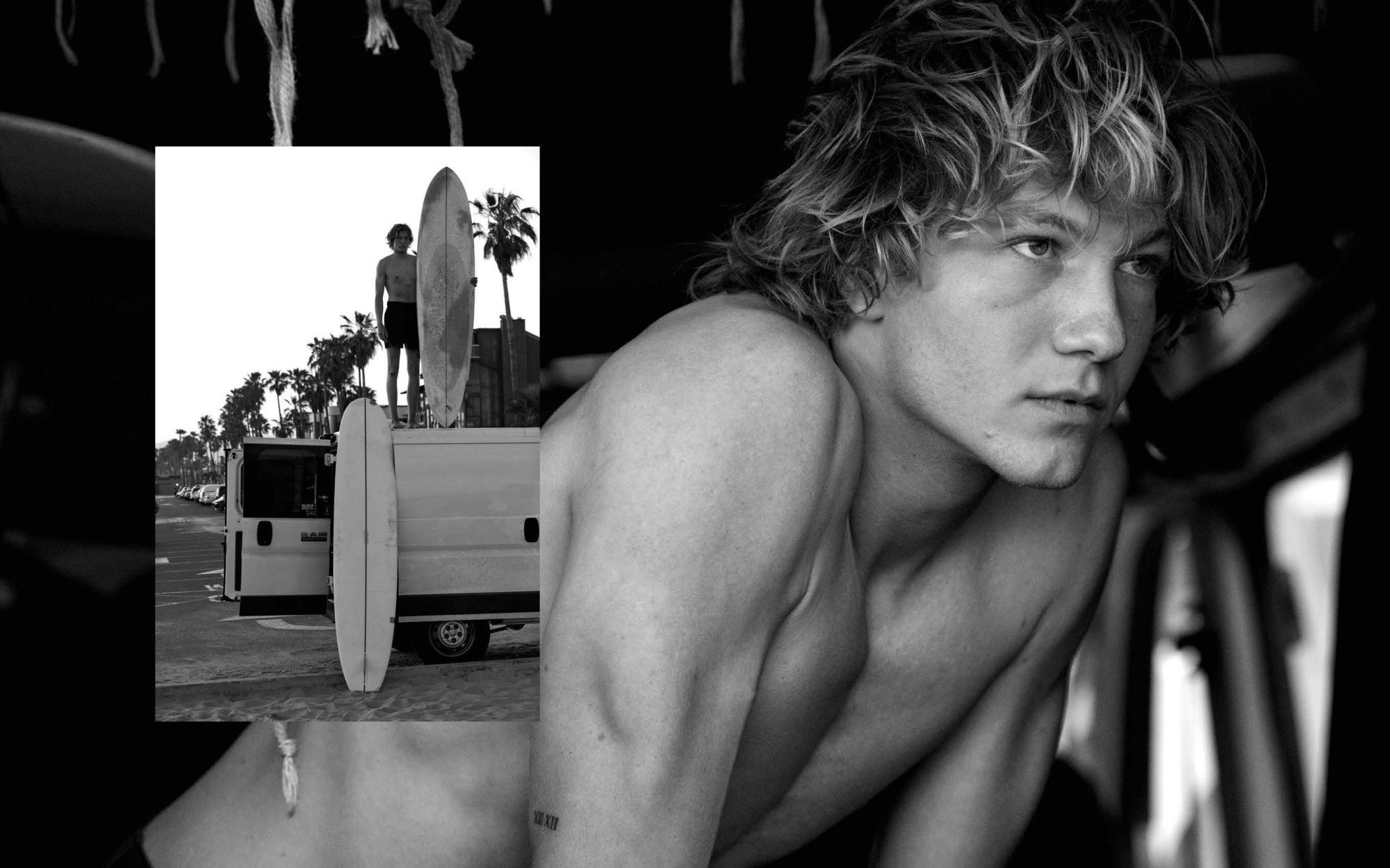

This particular California crew lives in pursuit of cresting coastal waters, and retreats to tricked-out personalized vehicles that enable itinerance. One surfer said of his van: “I view it more as an extension of me in a way. It’s like my shoes, or like ‘phone, wallet, keys.’” Exploring the visceral energy and low-key camaraderie of the scene, Brookes prizes glimpses of calm solitude over relentless adrenaline rush.

We exchanged with Matthew to discuss venturing into brisk pre-dawn waters, and fanboying over Peter Lindbergh.

You have a peripatetic background: born and raised in two countries, now living between two cities. How did your trajectory lead you to California?

It’s funny that you ask this question because it’s only recently, in looking back on my project of surf nomads, that I realized I’m a nomad myself. I was born in Sheffield, in England, and my family immigrated to South Africa when I was 9 years old. We moved around a lot when I was young.

Pre-pandemic I was taking, on average, 120 flights a year for work. After years of this, I felt at home in many places—or not totally settled anywhere… I’m not sure which? I moved from South Africa to Paris at the beginning of my photography career, which was 20 years ago. It was a slow start, but I came into my style as a young photographer after six years of hard slog. Once I shot my first perfume campaign, I gathered momentum.

I have lived between Paris and New York for the last 10 years. When the pandemic hit, I spent 2020 in Europe. Then, in 2021, I decided to move to LA for a complete change. My friends advised me to move to Venice Beach and there I discovered and immediately fell for the crazy unique atmosphere.

Which photographers shaped your eye and approach?

I never went to school for photography; I just picked up a camera and a manual on how to use it, and started shooting my friends. My only true photography education was looking at other photographers’ books, and trying to learn from how they shot. I fell in love with the classic black-and-white photographers: Avedon, Bruce Weber, Herb Ritts and Peter Lindbergh. Lindbergh was my idol. He managed to capture the raw beauty of women with no frills attached, as if capturing their souls. I remember looking at his work in a bookstore for the first time and tears came. What a master!

While making Into the Wild, were you purely an observer, or also a participant in the community, surfing and living in a van yourself?

Most of the time I was a pure spectator, but the surfers did take me on day trips up and down the California coast. There was a group of skaters who parked in my street in Venice one day: they lived in a school bus. These kids told me how they crossed America in their converted grungy mobile home full of bunk beds, a kitchen… the works. They were obsessed with the film Into the Wild—this is where my book title came from—and took me into the California desert and to the Sequoia forest in northern California, where they would skate in the craziest places. My book was originally about surfers and skaters, but I have so much material that the skating part will be the sequel.

How did you select your subjects?

The first surfer I met in Venice beach had the craziest van filled with surf boards, skateboards, a bed… I asked him if he traveled in his van and he said: “I live in it!” He explained to me how he and his friends have part-time jobs to make ends meet, but live for the waves. They travel, then sleep in parking lots next to the ocean to wake up next to it. He told me how he and his friends live for the “flow”—the surfer’s version of ‘the Force’ in Star Wars. I asked him if could introduce me to his friends, and he said: “sure!” I met the whole tribe, and they completely opened their world to me.

In terms of the shoots, did you follow any routines, or was it more spontaneous?

It was very spontaneous. After I photographed a few of them and they felt comfortable with the process, they started sending me messages: “The surf is good in this spot… do you wanna go?” I would follow, and in each spot there were other friends—so I would just go from one to the other, snapping shots while they surfed or hung out in the parking lots, using a documentary style.

The van life community is growing fast and furious on the coast of California, especially since the pandemic. Often the surfers have partners who live a “normal” life in an apartment, so they’d spend a few nights at their places, and would spend a few nights a week alone in their vans chasing waves and sleeping in beachfront parking areas.

Were the subjects comfortable in front of the camera? How did you coax them into their most “natural” disposition?

I think that’s the most difficult thing as a photographer: making people feel comfortable and gaining their trust. I never push too hard and I’m always very discreet with the camera. In the beginning, I just photographed them surfing. Slowly but surely, when they got used to me, they forgot I was there. Surfers love being photographed, to have a record of when they catch a good wave. If they saw a good shot, they’d say “Sick!”—surfer language for “I like it!”

You’ve previously focused on choreography and elegant exertion through dance. How does surfing compare to that athleticism and pure dedication?

I was blown away by the dedication of the ballet dancers, and I thought that surfers would be the opposite. But these guys and girls wake up with the sunrise every morning to surf (there is the occasional moonlight surf alone in the pitch dark). I found their commitment to the ocean inspiring. It’s quite a thing to wake up and jump into a freezing cold ocean and battle the waves—I tried it.

There seems to be this single-minded devotion to surfing: Would you describe it as an obsession? A religion? A lifestyle?

I would say all of the above. They live for surfing and the ocean as though they are part of it: watching the waves, reading the surf sets. They worship the ocean, and each has found their own secret connection to it. One surfer, Kandai, who’s from Japan, said: “I talk to the ocean through surfing.” Personally I love the ocean, but I don’t have the deep connection to it that these surfers have. It’s almost like the ocean connects them with the divine.

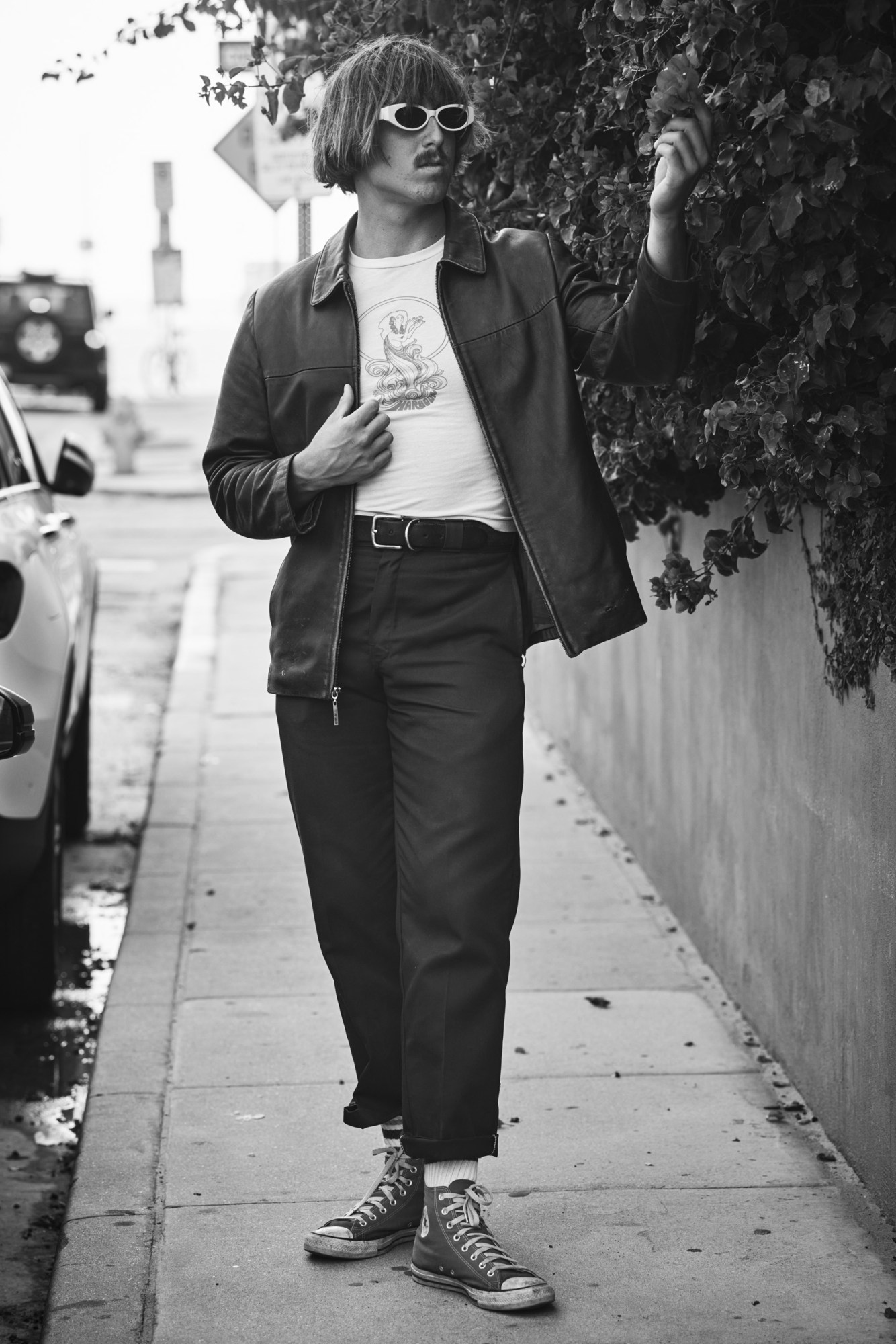

What do you think the series says about masculinity? On one hand, you have these classically ripped bodies—but then again there are super fun individual style choices like nail polish, rings, kerchiefs, glamorous sunglasses…

I don’t think you can define the way they dress as masculine or feminine: this is just their own personal style, what they feel like putting on for the day. From an outsider’s point of view, you could say that they were comfortable exploring their feminine side by painting their nails in all different colors or wearing a scarf over their head with a wetsuit, but I think they just enjoy being eccentric. Their version of what is cool does not seem to be gender-related. They had a kind of childlike naivety about playing dress-up.

Can you talk about the idea behind embellishing photographs with pastel colors?

I came across the work of a Spanish artist on Instagram called Juan Bertoni; I went crazy for it. I loved the way he drew on black-and-white pictures. I sent him a message saying that we should try a project together, and we immediately hit it off. I thought it would be a good complement because Venice Beach is like an explosion of pastel colors everywhere: pink, turquoise, yellow. I thought if I shot in black-and-white, and Juan drew on the images, I could show the grittiness and the playfulness.

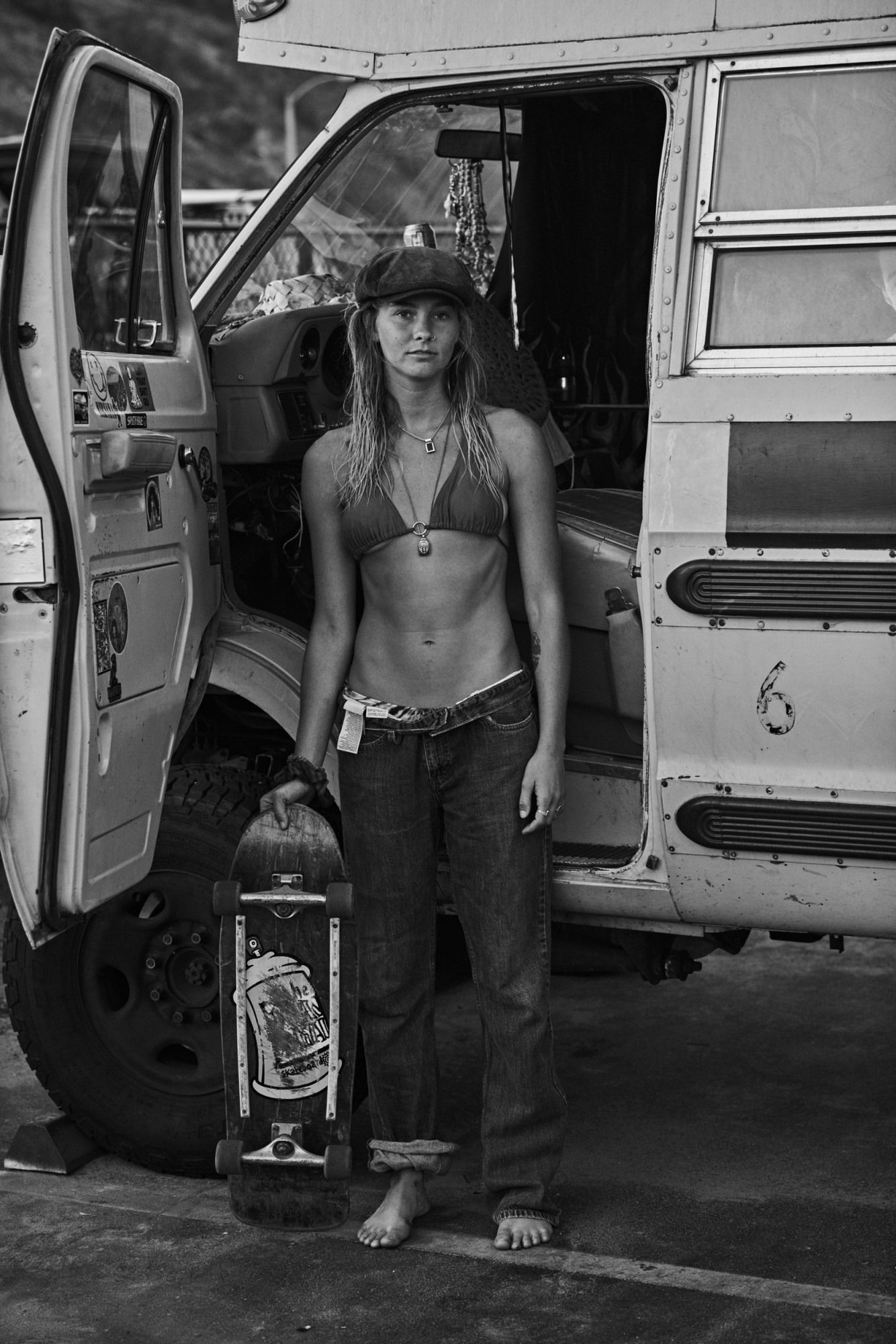

In terms of diversity of subjects, there are two women and two BIPOC men. Was this representative of the surf population you were seeing?

I would say that, on the whole, the surf community in California that I saw was predominantly caucasian. But within the surfer van guys and girls, it was far more diverse. I wanted to show an alternative to the stereotypical blond-haired California surfer.

Most subjects featured are young white men with few obligations except indulging what makes them happy. Did you have any worries about how this sector might be perceived?

That’s not what I got from these guys and girls at all, so if that is how people perceive this book, I’m afraid they missed the point. If they choose to live their lives for surfing, that doesn’t make them shallow. I think that, unless you live by the rules of the commercial world, you are judged and called lazy or less than. The point is to highlight the fact that some people are choosing an alternative way of living, and they are doing it in a positive way that makes them happy.

How familiar were you with other photographers who’ve captured surf culture? I think of Joni Sternbach as an immediate reference, among others… Was there anyone you were influenced by?

I actually don’t know the work of other surf photographers, because I just did not want to enter the subject with any subliminal images in my head. I wanted to capture this community as I saw them, and do it my own way. It can be hard to go into a subject artistically and have those voices saying, “Don’t shoot it like it has been shot before.” It’s much easier to start with a clean slate.