Solus Vol. I – the project Pieter Hugo has been creating, on and off, for about two years – isn’t his biggest concern the morning we speak. Over a phone call from Cape Town, he describes how burglars broke into the house he and his family are staying in last night, meaning he got very little sleep. A little trepidatious, yet enthusiastic to discuss work that hasn’t yet been discussed, he quickly launches in: “Let’s give it a bash and see how it goes.”

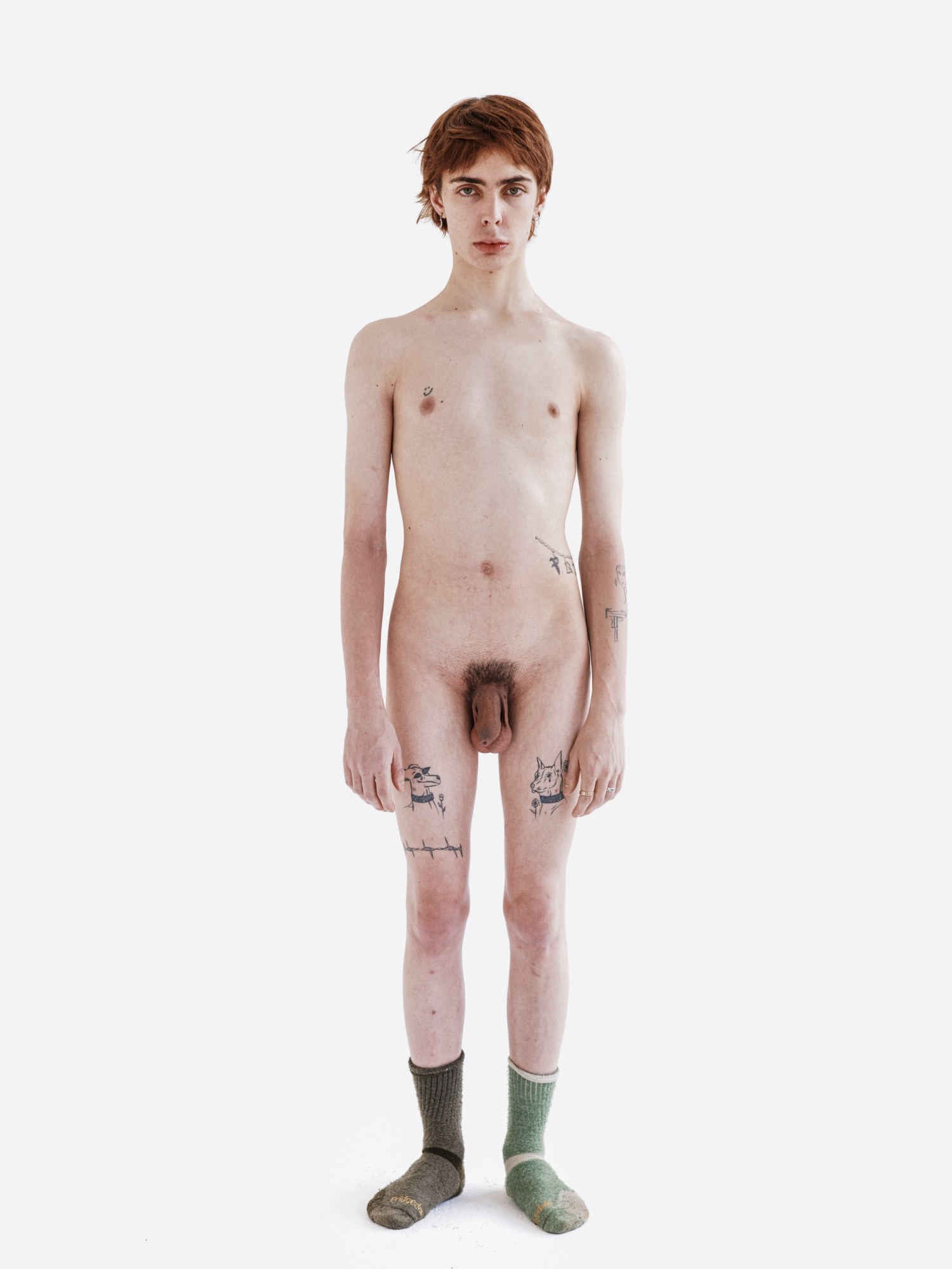

Composed entirely of studio-shot portraits — mostly headshots, though some are full-body and completely nude — at first glance this project feels like a shift for Pieter. Or, at least, a refinement. Here we find little more than a camera, a model, and a studio. There are no dramatic landscapes or latent symbolism, like the kind found in La Cucaracha, his contemplation of life and death in Mexico that was exhibited just before the pandemic, or the bulk of his archive. Yet all his subjects bear the signature Pieter Hugo gaze – a piercing look that bores deep inside you – found anywhere he turns his lens: in Mexican snake charmers; Jamaican porn stars; Nollywood actors; his children; himself. Holding the gaze of different models – cast by the agency Midland in Paris, London, New York, Cape Town and Johannesburg – with little else to distract or disarm, the effect is even more startling.

Originating from a journalistic background and shifting into the role of an art practitioner as his career passed, Pieter’s popularity and assignments from fashion brands and magazines took him somewhat by surprise a few years ago. Looking at the work fashion is so keen to tap into and reproduce right now, that of Kyle Weeks, Rahim Fortune, Kristin Lee-Moolman, Sam Rock, Jackie Nickerson, for example, a tension between fact and fiction seems present. Pieter, who began shooting in the early 90s, has interrogated this method of image-making. So perhaps Solus Vol. I could be viewed as a pared-back version of what Pieter has always been trying to say with his work. As he himself puts it, “I’m concerned with people and their appearance. I’m a portraitist. What people are wearing and how they present themselves is at the core of my work.”

Shot between 2019 and 2021, this project was first conceived two years earlier, on the set of a fashion shoot commissioned by M, Le magazine du Monde. Looking at the polaroids of the different models pinned up on the wall on set, it struck Pieter that the faces looking back at him were far more interesting than the ones that had gone through the “machinations” of the fashion industry – i.e. the hair and makeup and styling – and ended up in front of his camera. From there, he and Walter and Rachel of Midland, who had cast this M story, began discussing what could become of this idea. “In a certain way, I guess, the work has been ahead of me,” Pieter says. “I’m still catching up to it because there was an impulse to make the work, but I didn’t really know what about it was compelling. It’s taken me a couple of years to catch up to that impulse. So we started photographing.”

Pieter began in Paris, then London, and then New York. But, as with any ongoing project that commenced two years ago, Covid brought everything to a halt. Around the same time, he began questioning his role – the exchange between photographer and model – at such a tense moment, socially and politically. The pandemic was raging, and “the Black Lives Matter protests were happening,” Pieter says. “I felt like, as a white male, it was a good time to just shut up and listen and not a good time to put out work. I took a long break, a hiatus from this series, and when I felt a bit more even-keeled, I reached out to Rachel and Walter and said, ‘I think we should start working on this again’.” Travel was still impossible due to South Africa’s strict border policy and Red List status. “But they said, ‘Well actually, as it turns out, one of Walter’s really good friends who’s done casting for him happens to be stuck in South Africa as well.’ And I thought, okay, let’s expand this to Cape Town and Johannesburg. Just disrupt the narrative from the obvious fashion centres.”

When I spoke with Pieter last about a story he made of his family in lockdown during this downtime, mid-2020, these concerns with his place in photography were particularly raw. He was very reflective – so I ask if he can trace those changes or contemplations he had over that period in this particular work. “I don’t know if it is, in this series, such a strong relationship to the shifts that occurred during that period,” he says. But this series does say something about his past, and how he once looked to the future, he adds. “I came out of this 1994 era of South Africa getting liberated, and there was this incredible naive optimism at that time, which is subsequently falling apart. And always in post-revolution, it’s the scum that rises to the top. I guess in this project, in this era, within this epoch of strangeness and inclusivity, it’s just refreshing to have a reiteration of that, I think. It kind of just reminded me of what I identified with and what I wanted the world to be when I was younger.”

When asked about what that feels like now, living in South Africa, Pieter references the country as part of the “New World”. “It doesn’t have the historical baggage to what a country like the UK or France will have,” he says. “And what you also have is, when we had those elections, there was immense goodwill globally and locally to make things work. And a major readjustment for people to be inclusive, to be tolerant, to accept things like gay marriage — we had it written into our constitution. You know, it was an incredibly liberal experiment. Which, and as much as I identify with it, didn’t quite play out the way I think the architects of it had envisaged it to. But the premise of it I still very much agree with and identify with.”

“I’m still figuring this project out,” Pieter adds. “For something that’s so simple — it’s just portraits of people against a white background, how much more simple could it get really — but I’m still figuring out what it’s about.” There’s plenty more to say about these images beyond what we’ve discussed – the “hybridisation, or the convergence, of people’s heritage that can be examined via a portrait” for example, “and how the environment, whether it’s through physical factors or aesthetics, has imposed itself on people’s bodies.” A quote at the book’s opening that questions the very function and existential purpose of taking someone’s photo too throws up some interesting questions about this project.

But really, there’s just power in staring into someone’s eyes and seeing what looks back. As Pieter puts it: “There’s something about if one is held in somebody else’s gaze in the right way, there’s something so beautiful about it; something so life-affirming.”

Credits

Photography Pieter Hugo