Like most I came to the work of Alice Springs, aka June Newton, through the work of her husband, Helmut. Helmut’s images are seared into the consciousness of fashion, his impact revolutionary, his place in history secure. Maybe it’s more correct, though, to say I came to the work of Helmut Newton through the work of his wife, June; specifically an hour long documentary, Helmut by June, made in 1995. I knew Helmut’s work, of course, but it was this film that made me fall in love with it.

June had, a few years previously, bought Helmut a video camera for Christmas, and seeing he wasn’t interested in using it, picked it up herself and began to record their life together; from their homes in the South of France to Los Angeles, at work, at play, at life. It’s as perfect a portrait as anything either of them captured in black and white with a Rollei.

captures Helmut at work, crafting his photographs, directing the girls who were the stars of evocative, provocative, sexual images; Sigourney Weaver, Cindy Crawford, and Claudia Schiffer all pose and pout for Helmut’s lens. But the star of course is Helmut himself, and the way June captures him at work; his precision with a camera in his hands, the way he directs the minutest elements of the image to create his world.

June’s film dissects Helmut’s work, reveals how the magic happens. As a portrait of a master at work, it’s second to none. But what June captures so intimately, what makes the film really timeless, are the moments of repose after the flash bulb has been turned off, the camera put down, and the stylist’s clothes packed away. That’s to say it captures the tenderness, love, companionship, and humor of their relationship. The things that are hardest to capture. These are also all the things that June herself would capture in her images.

June was working as an actress in her native Australia when she met Helmut, who’d relocated there for work. Being Jewish, he’d had to flee his native Germany in the late 30s, after being briefly imprisoned in a concentration camp. Helmut eventually relocated to London, to work for British Vogue, before heading across the Channel to work for Vogue Paris, where he made his name and found his aesthetic, etching his name into the history of fashion photography with images that defined the erotically charged French cool of the 60s Left Bank. It was a fateful day in 1970 that led to June becoming Alice Springs.

Helmut, contracted to shoot an ad for classic French cigarette brand Gitanes, had come down with a bout of flu, and unable to contact the model to cancel at the last minute, showed June how to use a camera and got her to craft the image. The rest is history. She chose the name Alice Springs, a pun on a town in Australia; a hot, remote, and barren place, in the country’s geographic centre. Of course June’s photography was anything but remote and barren.

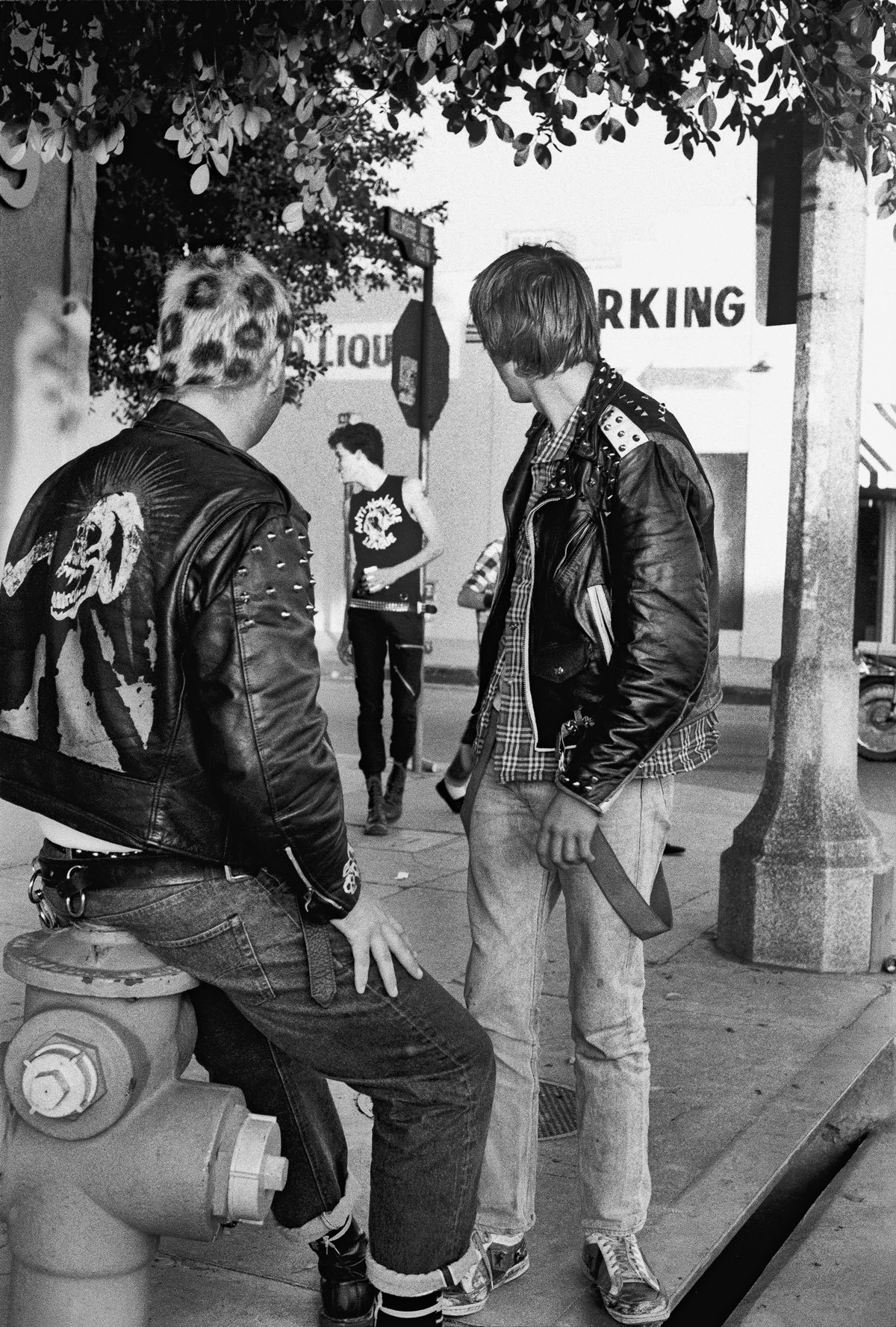

Over the course of her career she captured everything from the punk rockers and hip-hoppers of LA to the posh grand dames of the Upper East Side. June worked in fashion, portraiture, and documentary for magazine like Vanity Fair, Interview,and Vogue. She trained her lens on the leading lights of her time, from Yves Saint Laurent to Robert Mapplethorpe. All of which is the subject of a just-published new monograph on June’s work, and a new exhibition which opened at the Museum of European Photography in Paris last year, and is on until November at the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin. It’s the second of a two-part survey of June’s work as Alice Springs, and puts her in her rightful place as one of the unsung pioneers of the female lens.

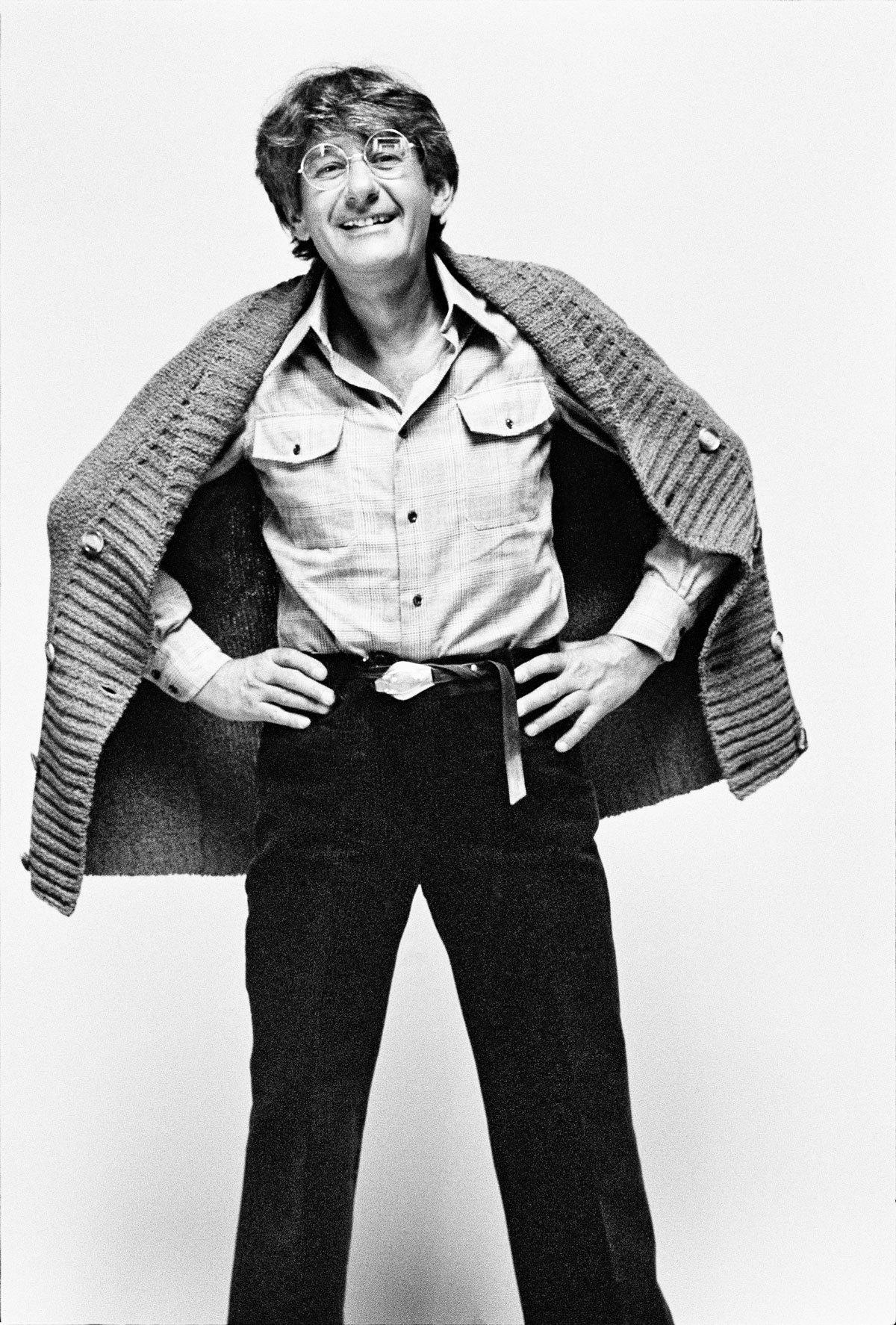

What’s clear, from the book and exhibition, is that June was a total natural with a camera. She had an expert eye for the unguarded moments that mixes with a Helmut-esque vision for a perfect pose; together they create something inscrutable and enigmatic that belies their surface simplicity. She often worked with Helmut, while he was on assignment, and there are plenty of magnetic images that capture Helmut at play and relaxing. She had a terrific sense of humor as an image maker. Observing her images, you can’t help but crack into a smile. There’s Helmut planting a kiss on the cheek of George Hurrel; with Bruce Weber, imitating him taking a picture; Helmut at work, looking either impish or bored; Helmut with Don McCullin and David Bailey, all looking very serious-photographer-like, except David Bailey has slipped his hand into Don’s pocket. There’s a beautiful image of Helmut, shirtless, goofing around with Pavarotti.

Not that we should merely think of June in relation to her husband. Just that much of her work was devoted to her life, and much of her life was spent with Helmut. She wasn’t just a great documentarian of Helmut’s life, but a great one, full stop. In the words of Helmut himself: “I don’t know of anyone else who takes the same kind of portraits… Hers have a unique quality… Her pictures of people are totally innocent.”

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography Alice Springs