The idea that online oversharing is unhealthy is hardly new, but 2020 saw a new, sharper-edged articulation of the concept. It all started with a Twitter account called Women Posting Their L’s Online, which was dedicated to screenshotting tweets posted by women which ostensibly concern a failure of some kind, serving these up for mockery to an audience of over two hundred thousand people. These L’s include things like getting cheated on or being a sex worker, neither of which should be considered a failure. The account has faced harsh criticism for being misogynistic, and it’s hard to see how anyone could seriously argue otherwise. It showcases both a gleeful revelling in women being unhappy and an unwillingness or inability to admit when women themselves are making a joke.

The account’s popularity (owing undoubtedly to the fact lots of men are misogynists) birthed a new trend. There’s E-Girls Posting Their L’s and the since-suspended Coomers Posting Their L’s (given that ‘coomers’ are a kind of pathetic and overly horny young man, this one represents a misandrist twist). Most shockingly and unforgivably of all, there was even one dedicated to poking fun at journalists — thankfully now deleted. These accounts are largely terrible and still remain a niche affair, but the term posting L’s has made its way into the cultural lexicon, a development which has encouraged people to look askew at a style of confessional posting which was once considered par-for-the-course. This goes hand-in-hand with a wider sea change. Separate to these often cruel gimmick accounts, more and more people seem to be coming to the conclusion that performing abjection and extreme self-deprecation online isn’t working for them. However much posting L’s might be tangled up in misogyny, I think this is broadly a good thing.

When it comes to posting L’s online, I’m a grizzled veteran, a former World Champion gone to seed. I have posted some truly deranged things on the internet, but more recently, I’ve managed to stop doing this much. This is partly because I now have a boyfriend and therefore have fewer L’s to post, but I also had a few wake-up calls. The first was Twitter messaging me from its official account to ask me if they could use a tweet of mine — which concerned going on a date with a man who had a boyfriend in a desperate attempt to make someone else jealous — on a billboard on the London underground. The second was receiving an ominous text from my mum, which read, “one of my friends has just texted me about your Twitter. Try to remember you’re not having a cosy little chat down the pub with your friends.” The third was the fact that I became a famous celebrity.

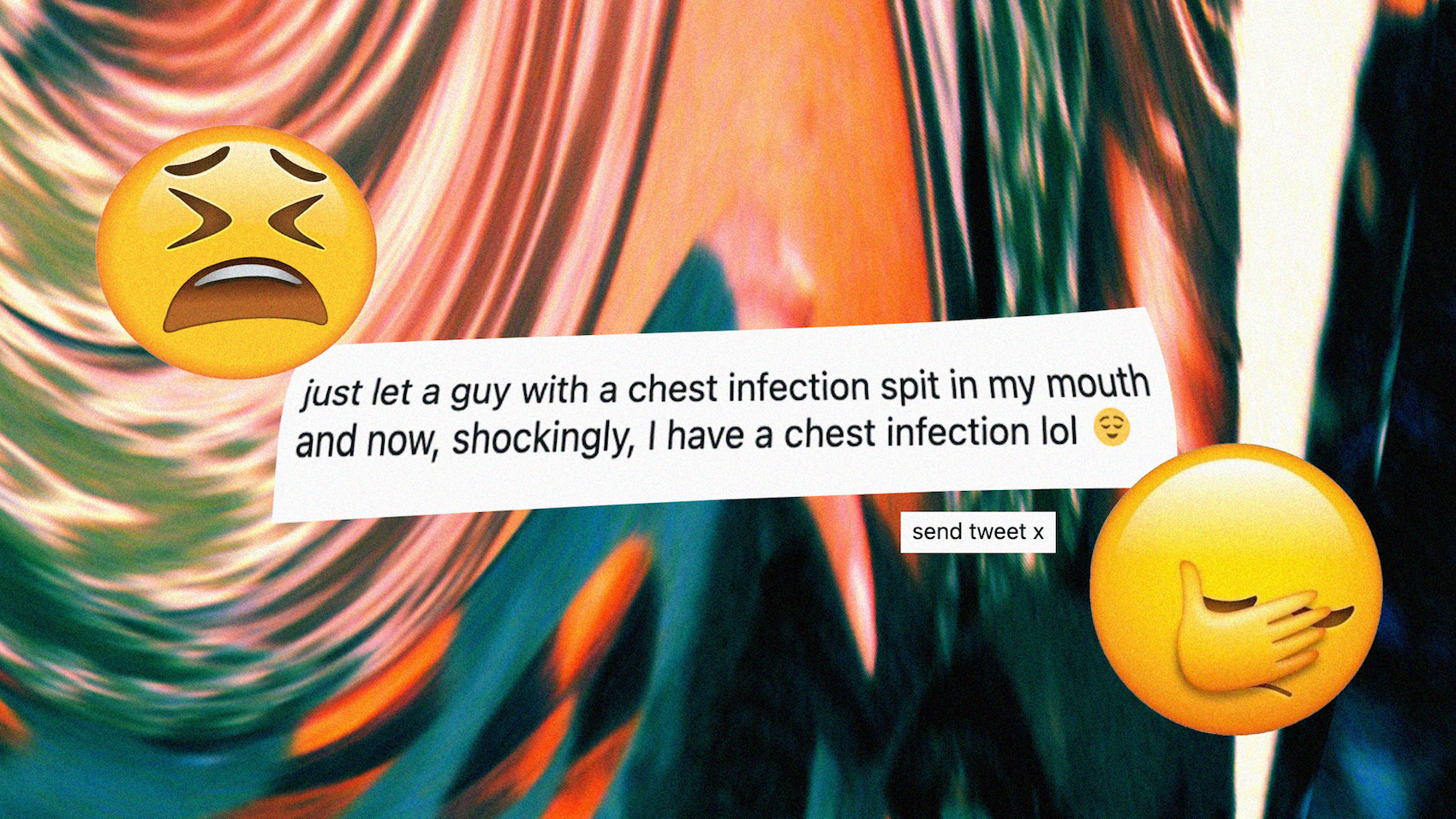

Most of the L’s we post online concern the world of dating. Reeling off a post about your romantic abjection can be a good way of venting in the short term, but it’s also a way of putting out a narrative about yourself that becomes harder and harder to stop believing (not to mention that other people, including anyone you might be looking to entice, can see it too). Take it from a man who once tweeted, “just let a guy with a chest infection spit in my mouth and now, shockingly, I have a chest infection lol”, depicting yourself as abject can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. “Sometimes these posts are just sad,” writer and journalist Hannah Williams, a committed advocate against posting L’s, tells me. “They’re often about how [they’ve been] treated badly, and I think sometimes there’s real pain behind them. Part of the reason people do this is because, to some extent, they feel a little ashamed and they don’t really want to reflect on it. Or they want people to laugh at it because it makes us feel better to think that the behaviour we’re exhibiting is actually just a big joke, rather than maybe a symptom of something we don’t want to deal with.”

“Reeling off a post about your romantic abjection can be a good way of venting in the short term, but it’s also a way of putting out a narrative about yourself that becomes harder and harder to stop believing.”

Posting L’s is usually a way of telling a certain story about yourself. To narrativise your life in this way is an attempt to create distance from it but — newsflash, honey! — you’re not actually the main character in a sitcom about a hot mess living in the big city. The credits don’t roll after a neat thirty minutes. You’re still doing the things that make you feel bad, and still sitting alone in your room thinking about them afterwards. In the face of this, writing a pithy social media post doesn’t provide much solace. Yes, it’s possible to turn pain into art. But “posting” isn’t really art. I understand the temptation to portray yourself as young, wild and absolutely craaazzzzzyy, but doing so risks standing in the way of getting the things you actually want. “It’s a very understandable instinct to immediately make yourself the butt of a joke so that nobody else can,” Hannah says. “But at the same time, you don’t have to make humour out of everything, for the consumption of everyone. While it’s obviously good if posting makes people feel less alone, I worry that it’s all being treated with this kind of joke-y social media register that means it’s seen as normal to be degraded when it isn’t.”

I think there are also some dangers here when it comes to mental health. You’ll be pleased to know that I wouldn’t describe experiencing mental illness as an L, but it certainly has a relationship with self-exposure. On the internet, we often see a kind of wry, ironically despairing register that goes hand-in-hand with being genuinely and unironically fucking miserable. The dominant piece of advice when it comes to mental health over the last years has been ‘open up and talk about how you’re feeling’. This is probably good — if limited — advice when it comes to friends and family, but you don’t owe that level of openness to everyone. After a bad spell of mental health problems, Dan, 26, made a conscious decision to be more cautious about what he shared online. “I justified it by thinking it’s good to be honest about struggles with mental health instead of pretending life is only positive,” he says. “I still think this, but I also think I took it too far sometimes and just lost any kind of filter between brain and keyboard. I was using Twitter to vent so much that that became pretty much the only purpose of the account. Especially during lockdown when I felt lonely, I was going on it while drinking and then waking up the next morning seeing overly honest posts that made me cringe, and in some cases, made people worry about me. Basically, I just realised that being a downer publicly was causing more stress than it was relieving.”

As unjust as it is, there is a stigma against mental illness, and the existence of this stigma means that talking about your own experiences in public is never an entirely risk-free endeavour. The fact that there exists a thriving subculture of accounts dedicated to humiliating people posting their lowest moments is surely a testament to that. Being open, honest and unashamed about your problems might help to improve these social attitudes in a fairly abstract and intangible way, but you specifically aren’t obliged to take up that mantle, and particularly not at times when you’re feeling vulnerable. And there’s probably more effective forms of campaigning than making jokes about your desire for “a crumb of serotonin”. If you’re really going through it with your mental health, you might not be in the best position to decide what is and isn’t an appropriate level of self-exposure, which is fine, and nothing to be judged for. But I think we should be more sceptical of the idea that openness is a positive or healing thing in itself.

“As a friend of mine fond of posting his L’s told me, ‘it’s a way of managing them, taking the shame and putting it into a broader context that feels like character development’.”

The catharsis posting L’s brings is rarely meaningful or lasting, but it’s undeniable that it can be really funny (one area in which the Women Posting Their L’s account falls flat is that many of the tweets it screenshots are simply good banter: we are being invited to laugh at these women but instead find ourselves laughing with them.) Lacerating self-deprecation has always been a rich source of humour, and I wouldn’t dream of issuing some kind of pious injunction against it. Sometimes the bleakest experiences make for the funniest jokes. As a friend of mine fond of posting his L’s told me, “it’s a way of managing them, taking the shame and putting it into a broader context that feels like character development. Adding a comic twist helps to take the sting out.” But you have to actually be funny to pull this off.

And even if your unhappiness is funny, or can be spun in such a way, there’s still the question of whether making it public is going to be a net benefit in your life — stand-up comedians are not, after all, typically renowned for being well-adjusted or happy people. It could be the case that you’re just humiliating yourself for the amusement of a braying audience of strangers who don’t even like you that much. Certainly, we shouldn’t make the mistake of imagining that everyone who follows us on social media is rooting for us or has our best interests at heart. I know that there are people out there who would be only too delighted to hear that I’m doing badly. Without wishing to inspire paranoia, it’s not wildly implausible to imagine that this is true of just about everybody with any kind of social media account, whether they’re a TikTok celebrity or a regular Joe on Facebook with a resentful ex-partner. Why give these people the satisfaction? I could talk publicly about my often poor mental health, I could tweet “I’m having a really bad time, guys. Please send cat pics!” But what would be the point? I don’t even like cats.

Sometimes, as I have written in i-D before, self-exposure can be a meaningful way of revealing subjectivities that are often marginalised or ignored. It can also be extremely funny and even insightful. And the literary and artistic canon would be slim indeed without people posting their L’s. There’s a reason Pride and Prejudice‘s Charlotte Lucas — “I’m twenty-seven years old, I’ve no money and no prospects. I’m already a burden to my parents and I’m frightened” — has found a natural and obvious home on TikTok in 2021. But I think we’d do well to have the integrity to take our own unhappiness seriously, at least for the most part, and save the posting of L’s as an occasional treat. It’s impossible to be truly mysterious with any level of visibility on social media, but if I could give my younger self one bit of advice, it would be: try to hold at least something back.