Today, the West’s obsession with Japan is pretty well established. From music, to fashion, beauty, and movies, our fascination is loving but at times also reductive. But in the mid 90s, it was a different story. Before Sofia Coppola set Scarlett Johansson adrift in Tokyo, or manga penetrated the U.S. mainstream, the reigning narratives about Japan were still dominated by images of the atom bomb and salary men. With this in mind, three young filmmakers set out to provide a different perspective.

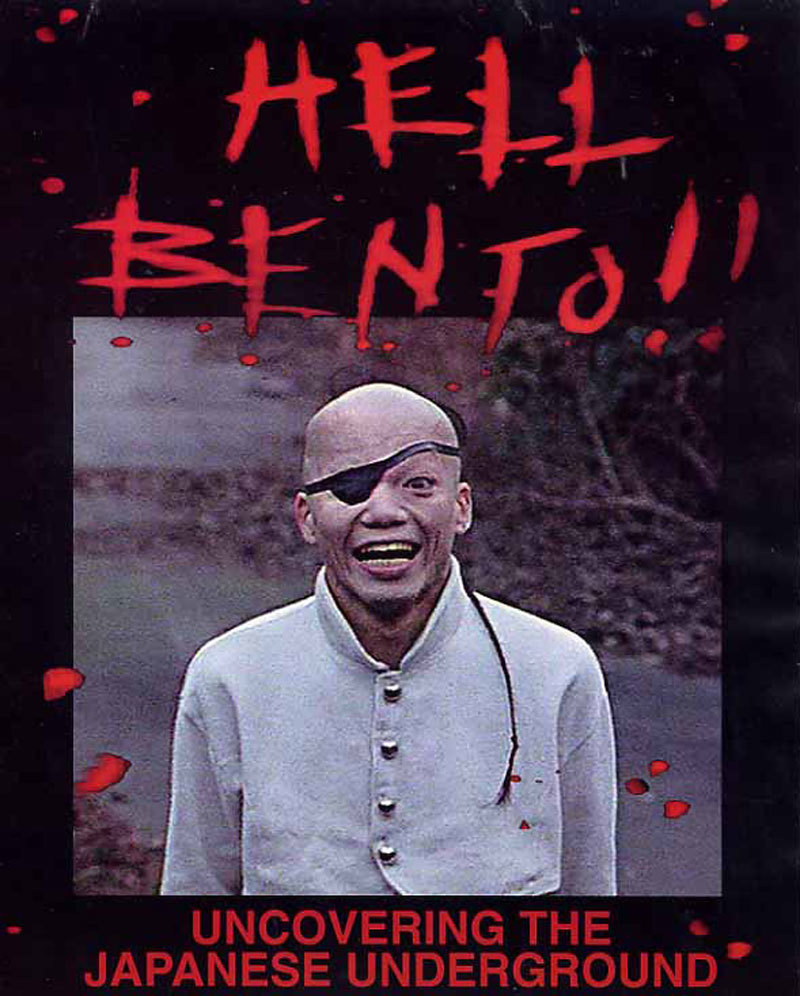

Anna and Adam Broinowski and Andrew Sully’s path to making Hell Bento sounds unbelievable today. The siblings, whose parents were diplomats, had spent part of their childhood and teen years in Japan. Their lives there were informed by an electric counterculture scene that was largely unexamined in the West. One day, they found themselves in a cafe scribbling down initial ideas for a documentary on a napkin. On a whim, they built it out into a one-page fax, and sent it to SBS (Special Broadcasting Service, an Australian television network), explaining they wanted to create a film exploring the Japanese underground. SBS liked their train of thought, and gave the trio $250k to make a one-hour film that would become Hell Bento.

Across one short hour, the filmmakers explore Japan’s noise music, bondage scene, 1950s “orientalism,” the LGBT community, a growing drug culture, the Yakuza, and the far-right nationalist movement. We’re also introduced to future heroes The 5.6.7.8’s, Guitar Wolf, and Merzbow. It’s a busy 60 minutes.

Ahead of Hell Bento‘s screening at a new Sydney festival For Film’s Sake later this month, i-D Australia called up Anna Broinowski to talk about Japan in the 90s.

In the mid 90s, the public cultural perception of Japan was very different than it is today. You’d partially grown up there and were more familiar with the nuances. But what were you really setting out to show with Hell Bento?

We were driven by a need to explode Western clichés, of which there were a lot. There was still a lot of bad feeling against Japan from the Second World War, and it angered us that there was this whole other side to Japanese culture that the world had no idea about. We were really enthusiastic about our friends in countercultures. We wanted to capture all of these ideas that were coming from these icons in Japan who were our age, our peers — who were revolutionary and amazing.

There were the Otaku Futurists, who were talking about the holy trinity of software and hardware. They were predicting social media long before it happened; they were hacking and all sorts of stuff. The queer counterculture we explored in Osaka was talking about AIDS when the Japanese government was just ignoring that it even existed. We just knew there was something new and amazing about these worlds.

A lot of this stuff hadn’t really been explored out of Japan. What were the complexities of being a foreigner trying to export these ideas?

We were really aware that, as foreigners, were were going in there and poaching this stuff. We didn’t do it in a way that was like, ‘let’s laugh at the funny Japanese.’ My brother and I shaved our hair, dyed it blonde, and carved Japanese characters into the back of our heads saying ‘exit.’ We were making fun of ourselves as outsiders. The Japanese countercultures looked at us and were like, ‘ok fine, they’re in on the joke.’

There’s a lot of talk about our obsession with Japan, but the film also explores how that is inverted. A lot of the characters are holding this wonky mirror up to Hollywood and the mainstream media. Did it change the way you looked at your own culture?

What I found was how critical they were about American imperialism, cultural imperialism. There was this underground group of Harley Davidson riding hipster types in black leather whose whole thing was to reclaim Japanese culture against the American imperialists who had taken over Japan. Back in the 90s, Japan was very much like Germany after the War — it was in denial. It didn’t want to go back to its nationalist self because that had ended in disaster. It wasn’t fashionable to be patriotic in Japan or in Australia.

Another thing we found interesting was how people like The 5.6.7.8’s were embracing American culture, but also parodying it. The lead singer of the band, a woman called Yoshiko [Fujiyama], was saying that her ideal woman is Jayne Mansfield for her decadence, she loves that. They were doing this sick exaggeration of American culture.

How do you feel about the way people approach and obsess over Japanese culture today?

I can’t pass judgement on that any more than I can pass judgement on any culture generalizing about another culture. It happens; there are stereotypes all around us. I like the fact that Australians seem to be plugged into the wackiness, the craziness, the beauty, and the nuance of Japan. I like that I have a friend who is a corporate person and is just doing Ikebana as a hobby. It feels to me that this is a very different world now from that which we made Hell Bento.

Australians are very familiar with Japan; beyond the stereotypes, there is quite a bit of knowledge now, which is wonderful. Maybe the new generations may have flattened out our idea of Japan, but it’s nowhere near as ignorant as what it was then. That’s a good thing and exciting.

A lot has changed since you made this film. Are you still connected to these people and places?

I’ve been back there a few times and I’ve gone to my old haunts, a lot of them are still there. I mean, it’s my other half. Some of the people we caught were really underground heroes. The director of the cabaret that was happening in Kyoto, I don’t think he’s with us any longer, but he was a hero of AIDS awareness in Japan. We were just very lucky to be there at this pivotal time where these movements we captured were under the radar, but about to bloom to the surface. Some of the people we met were quite extraordinary.

I think what interests me about Japan now is that the ones who were the underground are now coming to the mainstream. Under Trump, Japan is becoming Nationalist again, and that’s a scary thing. Because when the Japanese decide to be serious, they’re very serious. Watching that beast waking up is scary, but that seems to be happening in countries across the world.

How do you feel watching Hell Bento now?

I mean, it’s pretty dated now. When we made it time-lapse was the latest thing, but watching it now it looks so slow and daggy. Hopefully when people watch it they’ll enjoy it as a kind of retro artifact.

‘Hell Bento’ is screening with ‘I Will Treasure Your Friendship’ on April 27 as part of For Films Sake.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret