There was a time when a man was only as good as his best suit. In Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, William Lee, an aimless gay writer and addict played by Daniel Craig, stalks the streets of 1950s Mexico City wearing a summer-weight beige two-piece. Soiled around the edges and soaked with sweat and dregs of tequila, it’s the skin of a dandy undone: compact enough to be folded into a suitcase, made for drinking, cruising and going home to your typewriter – and heroin.

Queer, adapted from William S. Burroughs’ autobiographical novella of the same name, is the second costume collaboration between between Guadagnino and Jonathan Anderson, Loewe creative director and JW Anderson founder. For Anderson, finding a suit that was authentic to the period, one with texture and wear, was critical to fleshing out the character. “It is a period of time that, for me, is fundamental in the birth of the modern male,” Anderson says. “A period that is very subtle, but ultimately, there’s a lot of depth to what menswear was going through.”

Far from the thigh-baring short shorts and “I Told Ya” graphic tee of this year’s tennis epic Challengers, Queer takes a subdued (and steamier) approach to dressing desire. As we witness Lee’s growing obsession with a young discharged Navy serviceman named Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), the former’s rough glamour is set in direct erotic tension with Allerton’s muscular tailoring and translucent, close-fitting knits. Backed by Anderson’s research, which ranged from the first mass-produced WWII military wear to works by painter Michaël Borremans and photographer George Platt Lynes, the result is a sartorial sleight of hand that reflects Lee’s shifting perspective of Allerton as an object of a reality or – perhaps – pure illusion.

As you’d expect from his zeitgeist-defining fashion work, Anderson is more than comfortable taking the intricacies of his narrative ideas widescreen. “It is an amazing moment to escape from my day job, ultimately,” he says of working in film, “a way to transport myself. I think it helps me have the curiosity to go back in again.”

Let’s start with William Lee’s beige suit.

Jonathan Anderson: In the beginning, me and Luca had this idea that everything in the film would be original from the period. The suit became really important in the journey. It was important to try to get that right, for Lee – or William Burroughs – because I felt like it was going to anchor the entire film. After a lot of deep dive research on it, [I realised] this is a major turning point in menswear. It’s the first moment where, after the war, men’s suiting becomes industrialised.

It’s sort of the birth of the modern-day suit, this idea that you could buy it off the rack. A lot of companies would work with department stores like Sears to make these polyester-slash-wool or linen or viscose suits. Burroughs, when you look at very early pictures of him, was wearing them. After a lot of research, we found one, finally, that for me had enough burnout in it, in the knees and in the sleeves. I wanted something that looked very lived in, and you could feel the wearer in it. I didn’t want something to feel too stark, ultimately. It kind of inhabited itself, it was like putting on a suit that already was a kind of characterisation.

The body is so present. When you watch Daniel wearing it onscreen, you can feel the sweat, the odour, coming through.

When you think of cinema, you want to be able to smell it. You want to be able to feel like it’s immediately in front of you. You can never really get this from something which is new. There’s no history to it. You get this idea of a depth of field within this textural quality: that slub within the weave construction. [And] in the beautiful lens of Luca, which is film, you get this idea of a sharp type of texture.

You know, it’s [about] addiction. It’s the addict, and this idea that you become so consumed that you forget about the person that you are ultimately, or what you are wearing. There’s a thoughtfulness to that.

“With Lee, I wanted to start with a pristine white shirt, the sharpness of something like cocaine.”

I wanted to ask about the particular shade of the palette. It is complementary to Daniel Craig, but it also feels sort of unobtrusive, anonymous.

With Lee, I wanted this idea that you would start with a pristine white shirt, the sharpness of something like cocaine. Then as you go throughout the film, he starts to become darker and darker in what he wears. By the end of the film – his demise, ultimately – he is in a black suit. In the very beginning, I had this weird fantasy that we would dye everything in heroin. But this didn’t work out. [laughs]

How do you see Lee and Allerton’s wardrobes in conversation with each other?

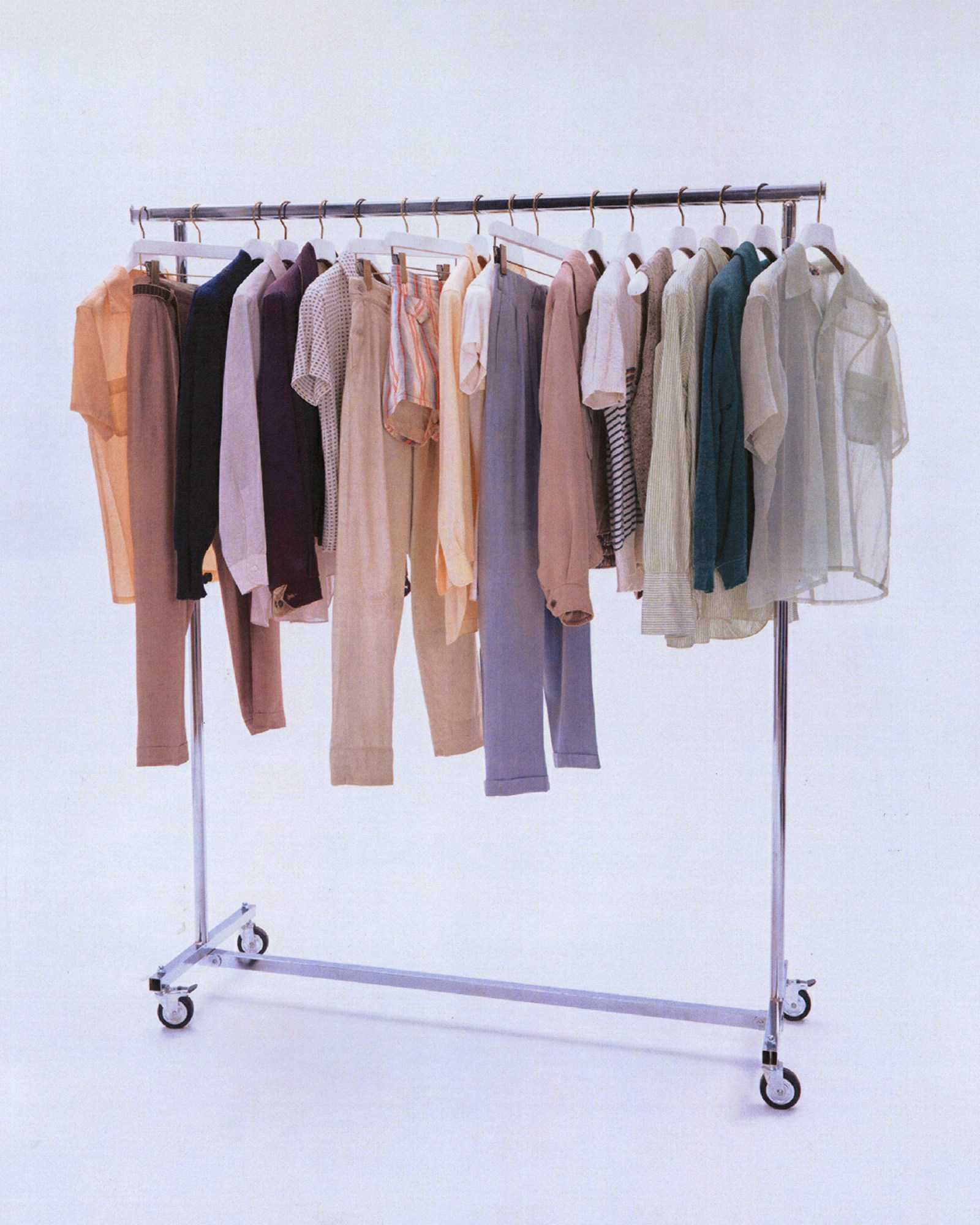

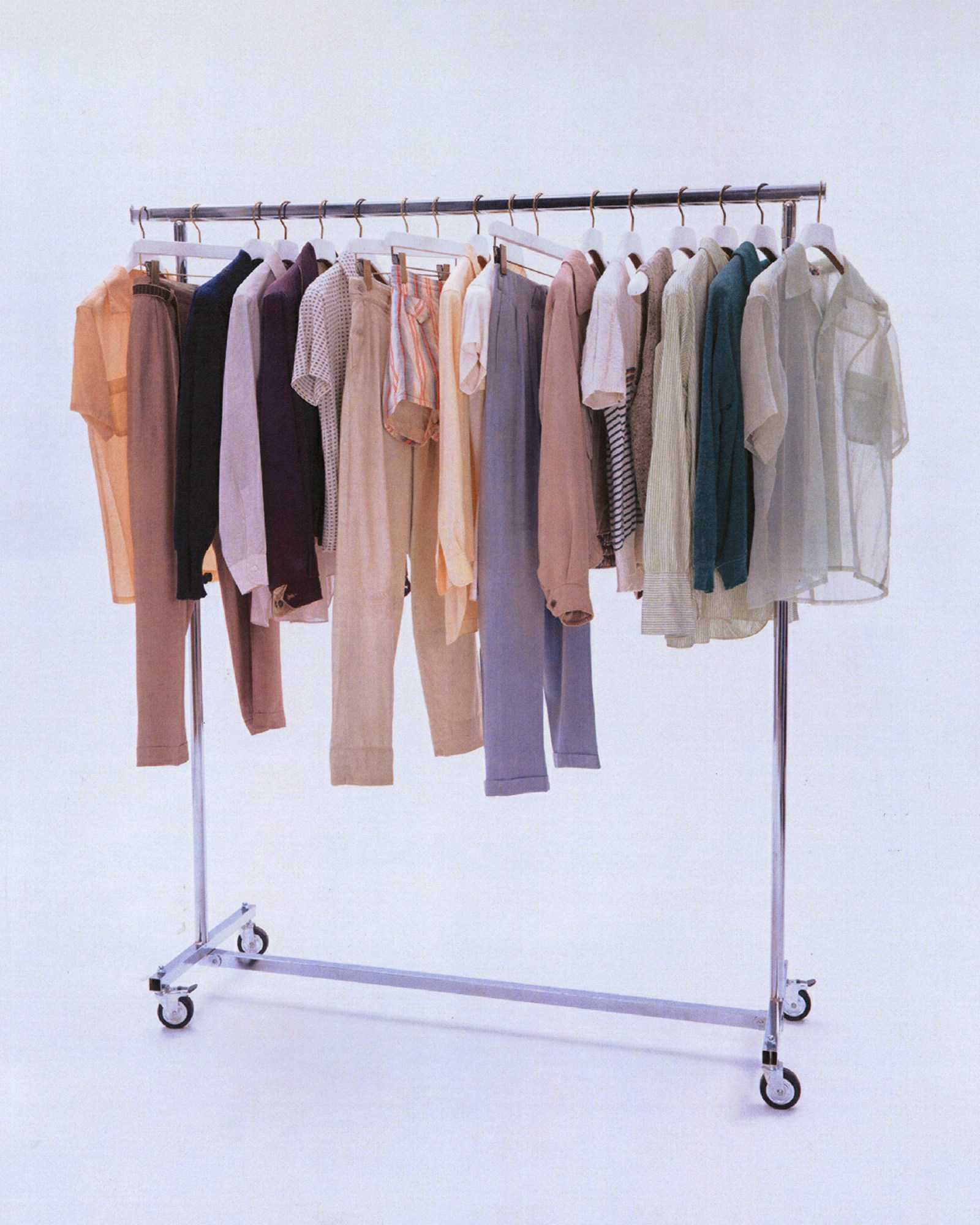

Ultimately you have to be able to grasp the character from the initial sight. For me, there’s a subtlety in the athleticness to Allerton, he is a lot more pent up. He looks more together, ultimately. But as you look at him, things have holes in it, or things are slightly just not as perfect as they seem. It’s this odd type of sartorial armour. When working with Drew [Starkey], it was quite nice to try to find this interchangeable wardrobe. Both Allerton and Lee’s wardrobe, you could fit into an entire suitcase; there were no duplications done of any garment. Every time I want to approach something, you’re trying to find a narrative within the execution of the clothing. It helps the storytelling aspect. So for me, Allerton had to have this odd type of precision, the belt, the trouser; suits in that period, where the waistband disappears inside the belt, and you get this incredibly elongated finish. Whereas, for Lee, everything’s falling off the body, it’s [almost] like there’s a carcass underneath. With Allerton, you have this idea of physique: how it relates to what is real, or not real.

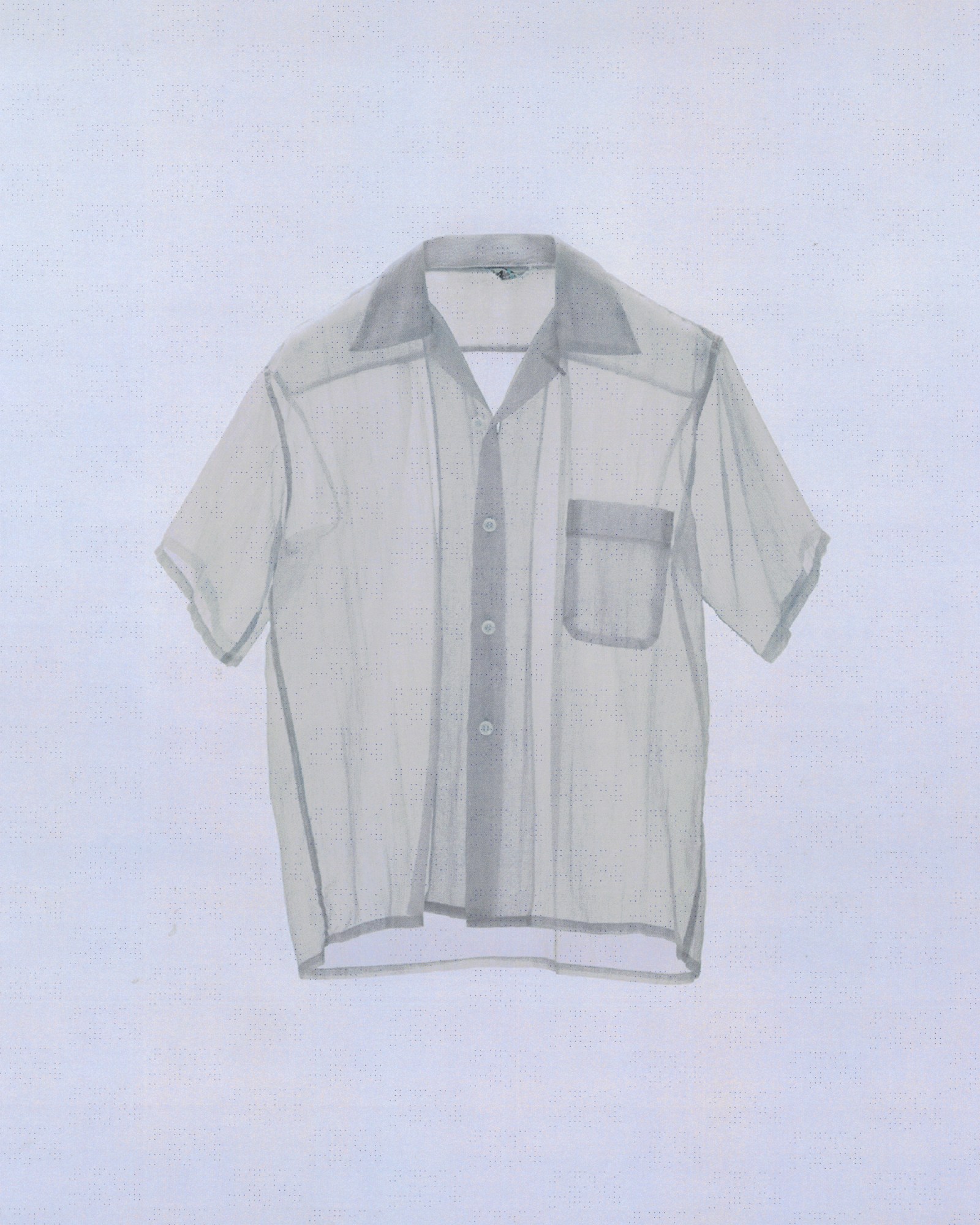

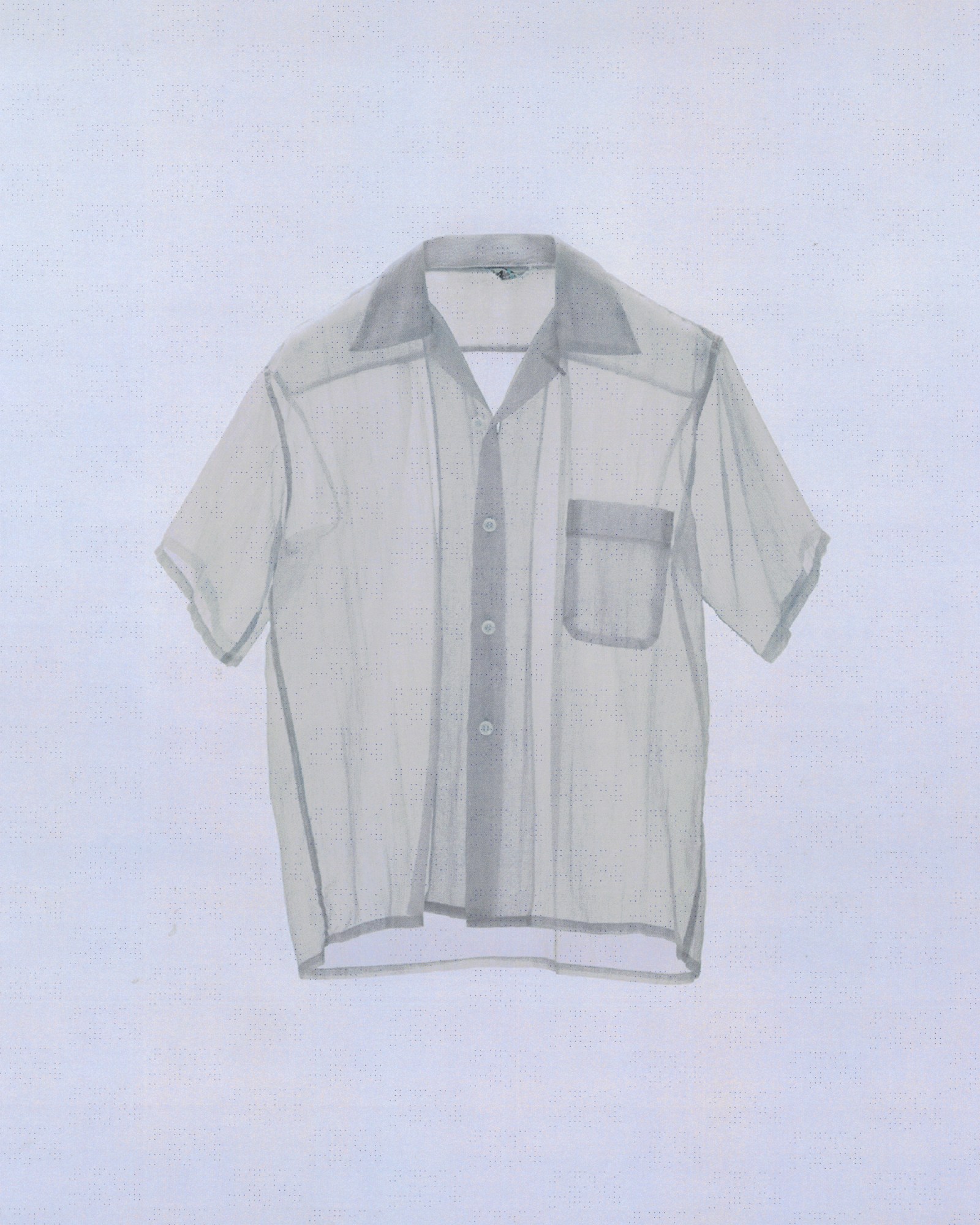

Also, in the book, you have references [of these characters] morphing into each other, and transparency. I found these incredible shirts from the 50s, which were translucent, and they had this very beautiful, opaque flesh colour, or pale, pale, pale green. What I liked is this seduces you into the idea: is Lee seeing something as a reality, or is he seeing it as a fantasy?

How much input did Luca have on the wardrobe trajectory?

Luca is one of the most amazing people when it comes to directors in terms of looking at the psychology of clothing. I think we underestimate the power of it, and what it says. Luca is able to capture that. He has a very textural mind, and really wants you to harness what you want to achieve in the film. I think this is why I love working with him. He trusts and he is there.

What about the collaboration with actors? I know Daniel suggested that Keith Haring watch in the final scene.

The key to working with an actor is to try to develop this other person. And someone like Daniel is such a dream to work with, because there’s a curiosity there that is renewing each time. Like when he came and brought the watch. I think Burroughs, in the end of his life, became incredibly, oddly vain, in terms of his status. People came on pilgrimages to come and see him. There was a knowingness of who he was. What Daniel captures in this, which I think is really, really difficult, is the psychological act of where Lee is.

What does working in film give you creatively that’s different from what you’re doing with your fashion work?

By doing both films, it’s helped me appreciate what I do, and expand. Instead of creating clothing, which then becomes part of a time period, you are delving into different time periods and relishing things that are not to do with you. I enjoy this kind of practice. It helps me have the curiosity to go back in again.

‘Queer’ opens in US cinemas via A24 on 27 November. It opens in the UK via MUBI on 13 December.