On a mission to prove that nightlife is alive and well, our Clubbing Isn’t Dead series explores the late night happenings of different cities, scenes and live-streamed video conference platforms.

As trivial as it sounds, one of the things I miss most about the halcyon age before coronavirus hit is the experience of going to clubs. The heat, the sweat, the proximity, borrowing a water bottle from a stranger and happily gulping down their saliva — it all seems unimaginable now. Two weeks into the lockdown, I look back now and think of every time I left the club early as a tragic waste.

This is far from being a unique lament: as well as being a leisure activity, clubbing acts as an important pressure valve for lots of people — something which I would argue is particularly true for queer people. Thankfully, a number of DJs and promoters have risen to the challenge of recreating the club experience within the new parameters we find ourselves in. Last Saturday, I decided to check out Club Quarantine, one of the indisputable leaders of the trend. Club Q is based in Toronto and was co-founded by four queer Torontonians: comedian and producer Brad Allen, digital creator Mingus New, DJ and musician Casey MQ, and recording artist Andrés Sierra. Their creation is providing a vestige of hedonism for bored and locked-down queers across the world.

Having already hosted appearances from the likes of Charli XCX, Tinashe and Kim Petras, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to describe Club Quarantine as a global phenomenon. Given that the LGBT+ community have always been at the forefront in developments in internet culture — from early dating and hook-up apps providing a template for their straight successors, to the strong presence we’ve always had on social media — it’s no surprise that queers are at the vanguard of coronavirus nightlife. It’s a nice idea but, more importantly, is it actually fun?

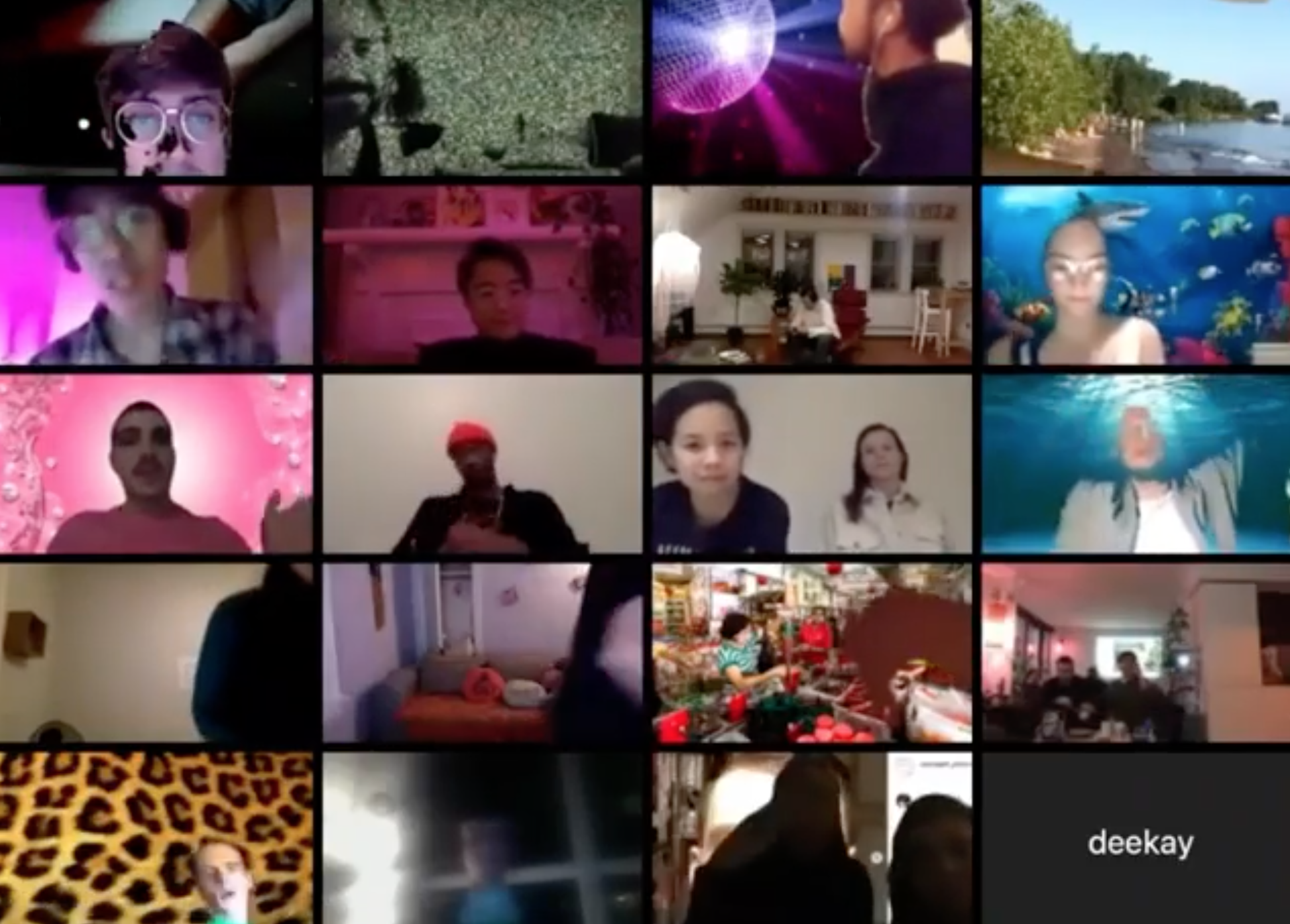

Club Quarantine is broadcast over Zoom — a video-chat platform designed for corporate meetings and working from home. Unlike the cheerier Houseparty, the interface of the app itself has a chilly corporate aesthetic which seems ill-fitting for an untrammelled night of decadence. When you log in, you can see yourself in a little box on the top of the screen and if you click on a grid you can see a segment of everyone else who’s tuned in. The main screen is alternately streaming the DJ and people chosen at random. Knowing you can be seen by other people feels surprisingly exposing, but not entirely in a bad way — the simple fact of being on display gave me a kind of energy boost. This is the chief difference from simply watching a stream or a Boiler Room set on YouTube — you feel less stupid dancing alone than you would do dancing to a stream. Maybe it simply appeals to a narcissistic desire to show off for an audience on the internet, but other people dancing to the exact same music as you are does provide a communal experience, or at least a glimmer of one.

“When I first tried Queer House Party [a similar night to Club Quarantine], I thought it would feel really contrived and that we would just be alone in the living room starting at the TV, but it was a really joyful and fun night,” says Cara English, who works for trans youth charity Gendered Intelligence and is an enthusiastic early adopter of this genre of night. “It took me by massive surprise,” she says. “I had a friend and his flatmate ‘at the party‘ too and he said it was the closest he’s felt to seeing people in real life in weeks, like we were actually at the club together. I don’t think it’s the same as being at an IRL party but in many ways it was better. If people were wasted they couldn’t annoy you, no one could smoke around you.”

Perhaps the most important aspect of queer clubbing is the sense of community it provides, the opportunity to socialise with people like yourself. How does this translate in a digital context? Surprisingly well. You can also send a message to anyone there, and there’s a communal group chat at the side, where you see people saying things like ‘I’m so glad I found this.’ and ‘I felt so lonely before’, and making affirmative statements about trans rights, which made me more inclined to abandon the cynicism I had when I initially logged in. You could flirt with people, you could theoretically meet and fall in love with someone, which does allow for that ‘anything could happen’ atmosphere which makes clubbing so appealing. My contribution to the group chat mostly consisted of such penetrating insights as ’Wheyy!!’, ’what a tune!’ and ’does anyone know the name of this DJ!?’. But it probably wasn’t the forum for in-depth analysis of those Financial Times graphs about global infection rates — I don’t think the conversation really needed to be any deeper than it was.

Just like any queer club night worth its salt, there’s a real variety in who is using it and what they appear to be getting out of it. Some people are dancing topless in over-the-top outfits, gold lamé hot-pants and stuff, while others are just vaguely swivelling in their desk chairs. Some people are racking up lines of white powder and others are sipping cups of tea. Surprisingly no one was exposing their genitals — I would have thought that digital flashing would be an unavoidable aspect of a platform like this. Some people are with their friends and look like they’re having genuine, non-digital fun which simply made me feel envious rather than less lonely. I guess the problem with the concept is that it looks like much more of a fun thing to dip in and out of when you’re actually hanging out with people IRL, which means it doesn’t really solve the problem of social distancing isolation. But I also found the idea that this was happening every night comforting. Even outside of the context of the pandemic, this would be an excellent thing to do if you just found yourself too skint to go out on a Saturday. It’s also highly accessible to disabled people, which is great. For these reasons, I hope this night and others like it (most notably, Queer House Party) outlast the pandemic.

Inspired by Club Quarantine’s success, established queer promoters are now looking to Zoom as their next venue. Hannah Williams, co-founder of South London queer night Suga Rush, is currently in the process of setting up a digital version of the night. “We decided to do this for two reasons,” she says. “Firstly, we want to get people to donate to our old venue The Chateau’s relief fund for their artists and workers, because obviously the situation is bleak right now for unemployed and precariously employed people.Secondly, we want to do it because it’s quite silly and should be quite cute and fun — it would be be nice to do something lighthearted rather than trawling through Twitter to read more horrendous news articles from the last few hours. Also, I think people want an excuse to dress up and look hot again.”

Even for experienced promoters, organising a club night of this nature poses a completely new set of challenges. “I think there’s something, perhaps inherent to tiny queer clubs, about seeing everybody being so unconcerned and present,” says Hannah, “that creates a kind of mutual understanding in clubs. I’m worried we won’t be able to recreate that and I’ll miss that a lot. I’m worried about looking like a dick. I’m worried no one will turn up. I’m worried I won’t be able to play the music properly or my laptop won’t work! But I guess it’s all a learning curve.” Cara agrees that there are aspects of the conventional night out experience which are hard to capture. “Sometimes you need the sweat, the deafening reverb and the wasted conversations with strangers in the smoking bit and the falafel on the way home,” she says. “When the night ended and we just found ourselves in our living room, we thought ‘oh… this is convenient and all but where’s the night bus drama?’”

The experience of a digital club night can look pretty grim and cheerless on a screenshot, but what a static image fails to capture is how vibrant it actually feels. Every single panel is pulsing with life. So what use is it to say that I ultimately found it nowhere near as satisfying as the real thing? Could anyone really have expected otherwise? Just like Houseparty isn’t as good as an actual house party, a queer club night on Zoom is never going to be as fun as an actual club. But it’s the best we’ve got and it’s really nice that people are trying.