When photographer Sunil Gupta arrived in London in 1978, he realised the queer scene in the British capital was nothing like what he had been used to in New York, where he had been living during the 70s. After the Stonewall Riots of 1969, in the years before AIDS made its mark on the community, Sunil became accustomed to seeing people openly cruising New York, his famous Christopher Street series from 1976 capturing the gay men of the city as they confidently and nonchalantly walked its streets. “People were on display,” Sunil says. “They wanted to be seen and identified.”

London, on the other hand, felt different. With licensing laws that restricted the opening hours of pubs and ‘pretty police’ (policemen in disguise that would target gay men suspected of sexual wrongdoing), it was a comparatively hostile environment for queer people. Same-sex relationships had been decriminalised in the Sexual Offences Act of 1967, but only if you were over 21, were having sex with just one other person, and doing it all ‘in private’. “The times were really bad to go out,” Sunil remembers. “It was illegal to cruise, basically. If I walked over to someone to try and pick them up, it became an offence. How else were you going to meet anyone?”

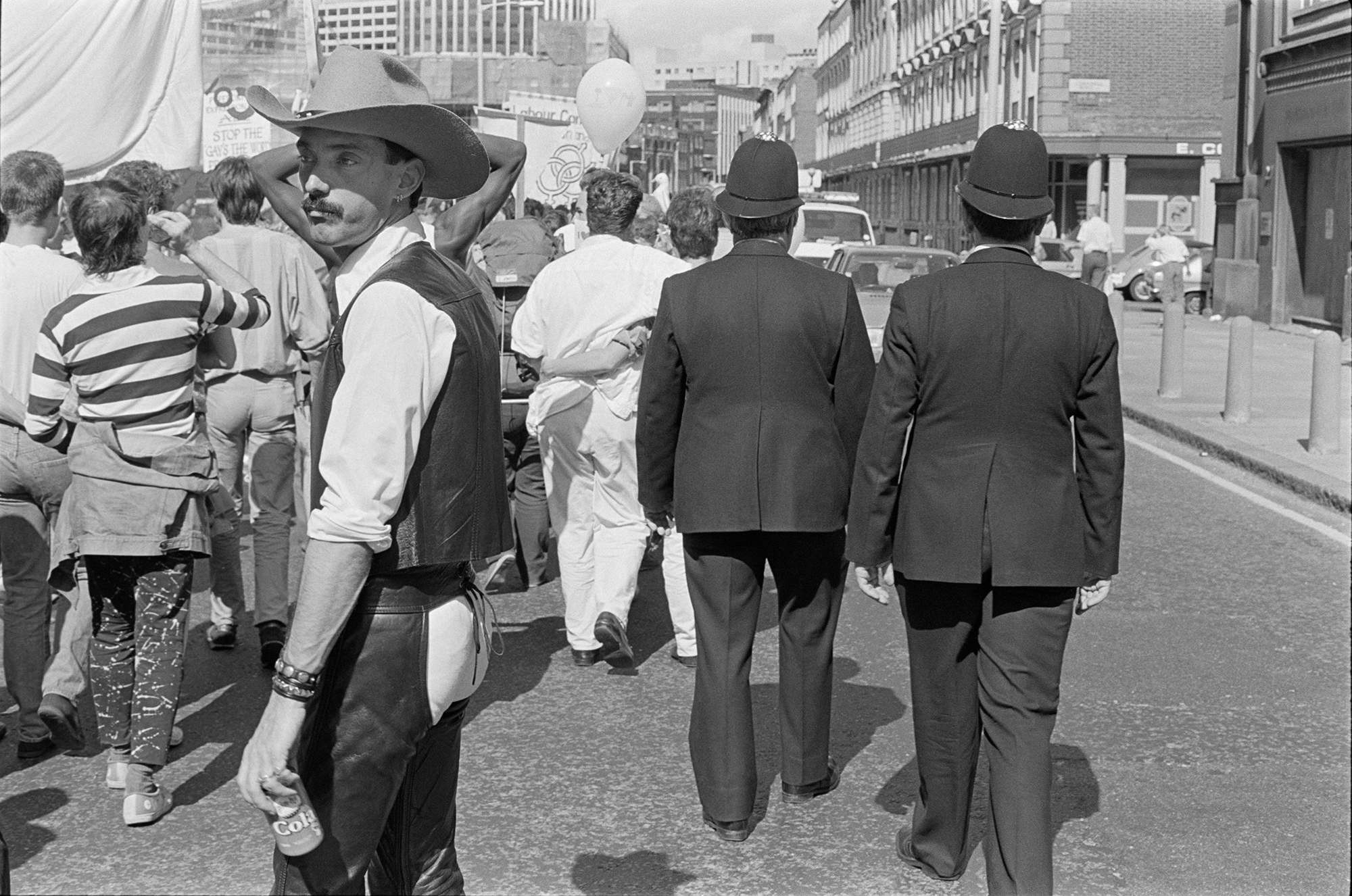

Things began to slowly change in the capital with the establishment of the London Gay Liberation Front in 1970 at the London School of Economics. “It was a small number of people at first,” Sunil says. In the early marches, small groups would walk down Oxford Street and end up at the University of London. They were mostly just undergraduate students. “But in the 80s, protests began to grow,” he says. With time, people started gaining collective confidence, and built up the momentum to protest on the streets — and not only about LGBT rights. “We joined rallies about peace and nuclear disarmament, as well,” Sunil says. “All the strikes during the Thatcher era.”

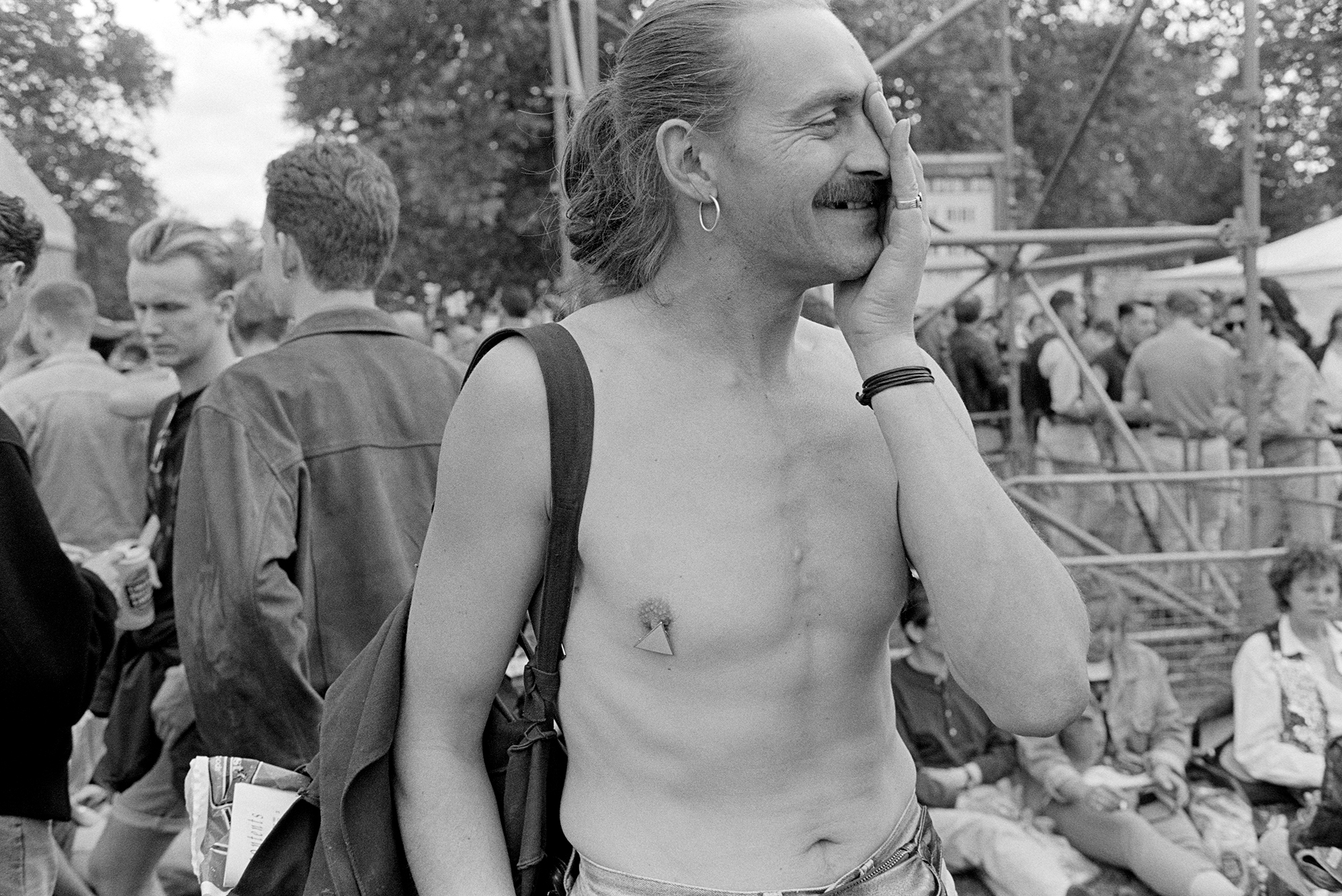

During those marches, Sunil would stop and take photographs. He took portraits of people smiling as they held ‘Body Positive’ banners, blurred shots of crowds on street corners emerging out of tube stations, and stills of couples embracing each other as they walked in procession alongside others. Sunil wanted to capture these events through his lens, from an insider’s perspective. “At the time, there were many discussions about pictures of marches, of people and the media taking pictures from the outside,” he says. “I felt that, as a photographer, I didn’t want to contribute to that kind of media representation. I wanted it to be something more personal and more subjective, just documenting our history.”

These photographs appear in Come Out 1985-1995, Sunil’s new photobook that looks back at his memories of the protests and Pride parades that took place in London in that decade. Fleeting details in certain photographs create a distinct sense of place: the words ‘National Gallery’ inscribed on the walls of a museum, or the neon Philips and Panasonic advertisements formerly wrapped around Piccadilly Circus.

Some of the pictures featured in Come Out were taken in the neighbourhoods of south London, where Sunil lived. “We were all living and hanging around in the same places,” Sunil says. “For a while, the marches would end in Brockwell Park in Brixton [or] in Kennington Park. We would march down that long Kennington Road. People wanted to end up at a party in their community, more than in the middle of central London, to make the marches more accessible and also be in our local part of the city.”

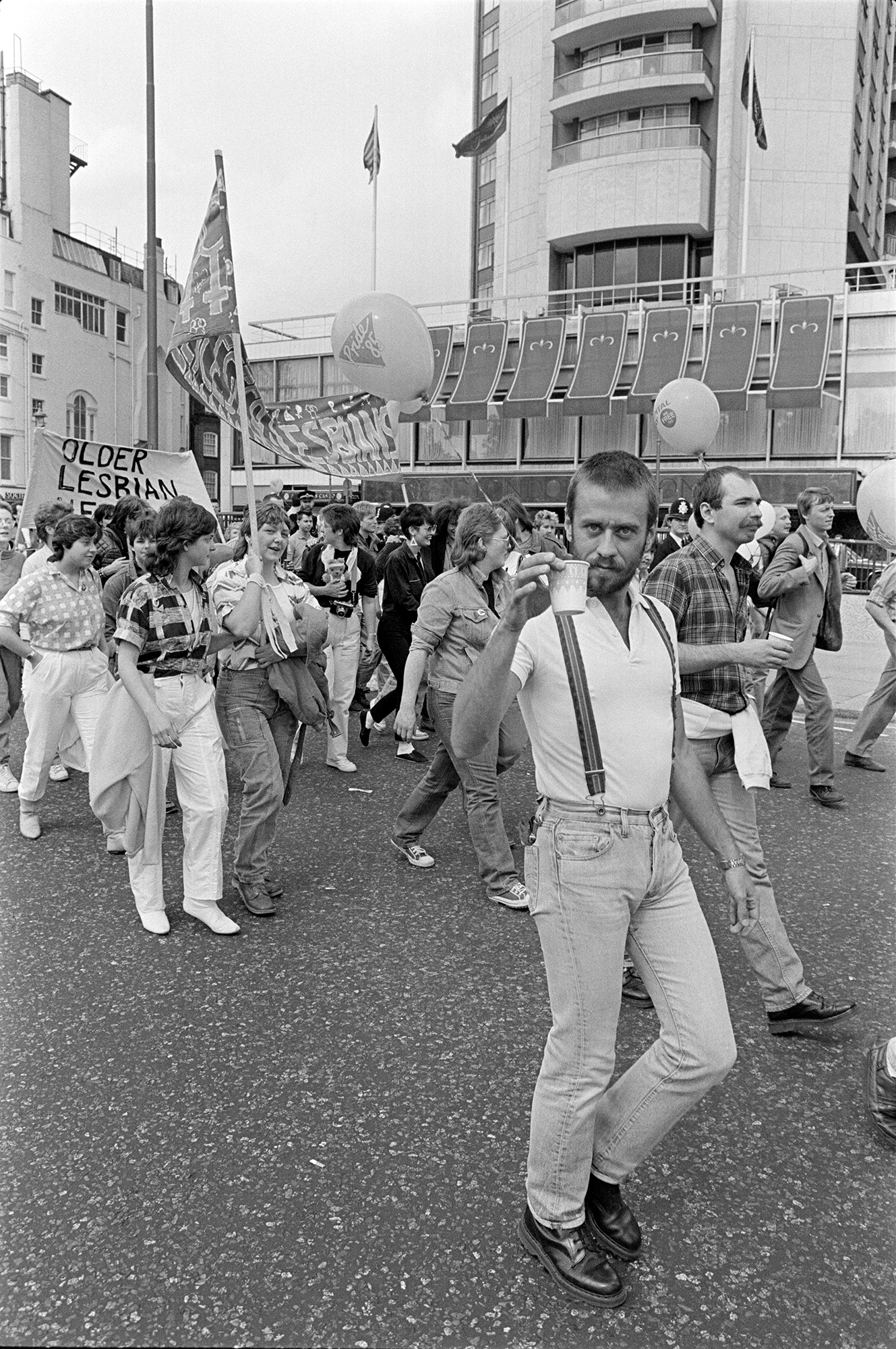

To pin down that sense of community, Sunil photographs the people he knew from that era in the places most familiar to them. In one photograph taken at Pride 1985, a man cheers to the camera, a paper cup in hand. In another, a woman is caught mid-sentence, speaking directly to the camera. Sunil often encouraged them to react to the camera’s click. “I was trying to shoot something from within, so these are people that I mostly knew or recognised,” he says.

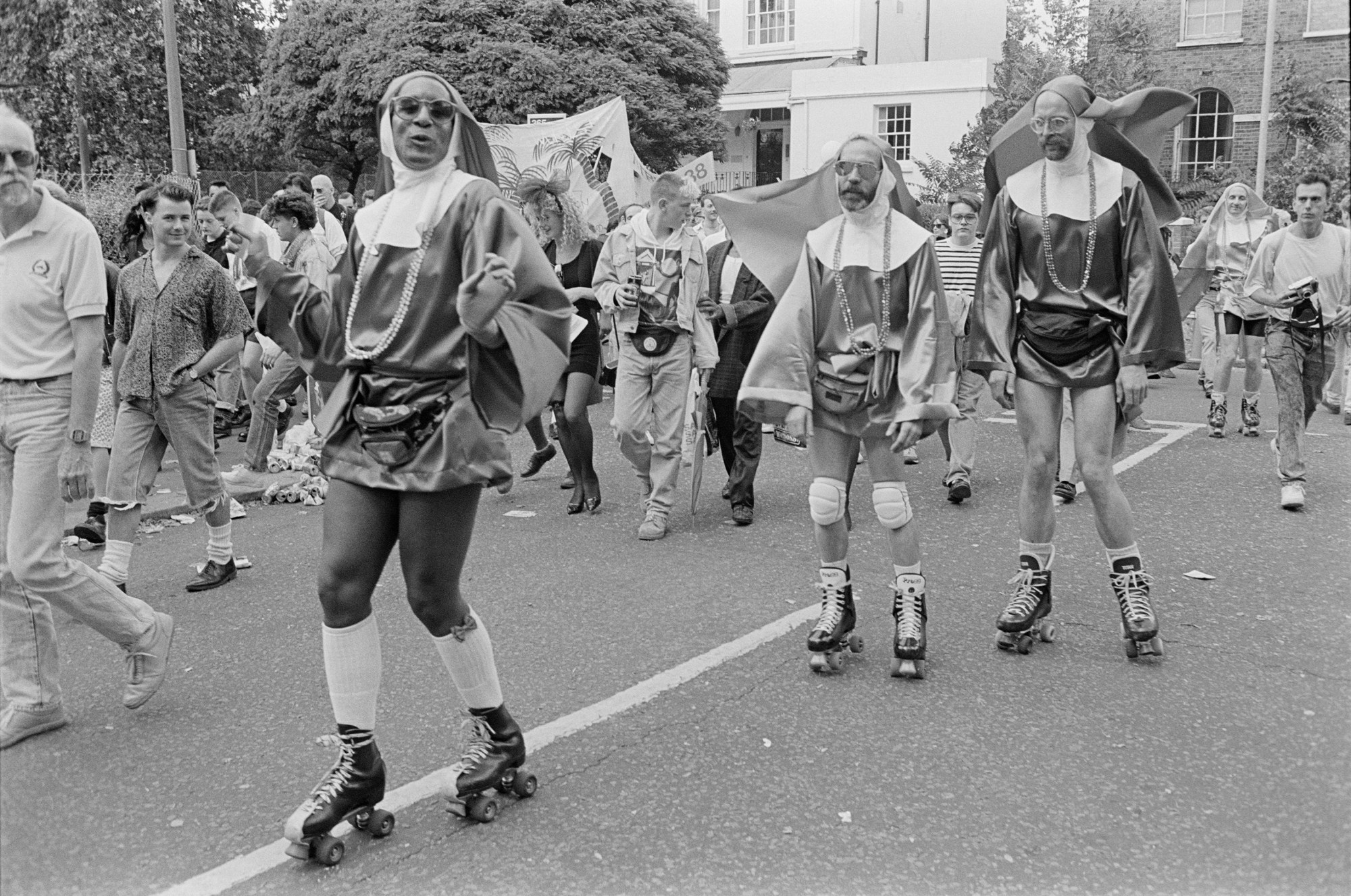

Sunil interweaves years, places and protests together in Come Out. Stills of people wearing bondage suits or dressed as nuns appear among photographs of people holding banners supporting the Miners’ Strikes in 1985, or posters condemning Section 28 in 1988. The years in which the photographs were taken are only suggested through small textual details in the images themselves, like ‘Pride 85’ written on a balloon or ‘Pride 90’ printed on a man’s T-shirt. “Come Out wasn’t meant to be a proper document of the decade. The exact year doesn’t matter to me,” Sunil says. “It’s more about the period. These are just taken from a bunch of photographs that I had shot at different marches that I never had had the opportunity to share because they were quite personal. When I took them, I didn’t want them to be in the media and for them to talk about those people — because they were my people. Now, the people have become old enough where I can make this book. It’s really just about my tribe, my people.”

‘Come Out’ is published by Stanley/Barker and is available to buy here.

Credits

All photographs lifted from ‘Come Out, 1985-1995’. © Sunil Gupta, courtesy Stanley/Barker