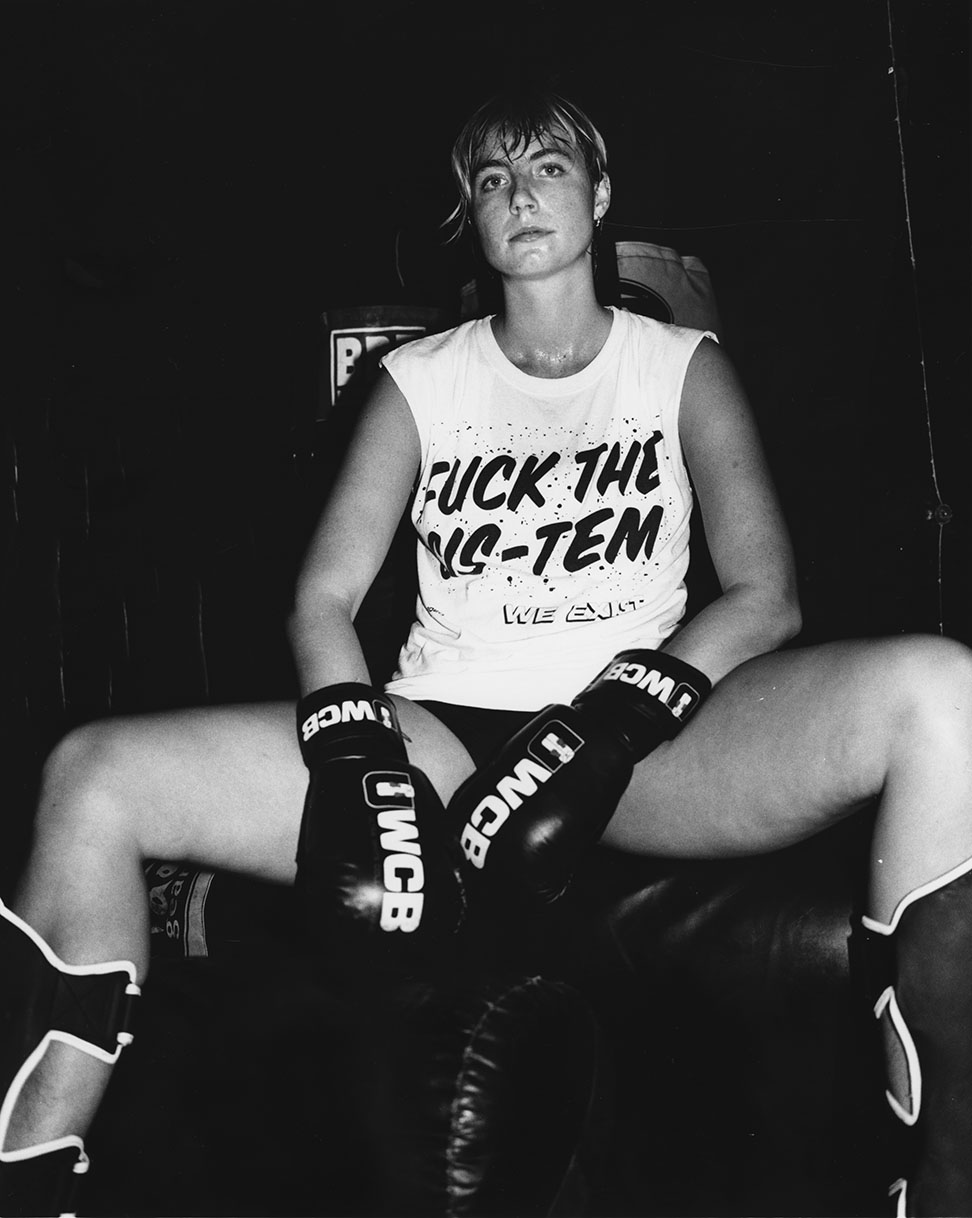

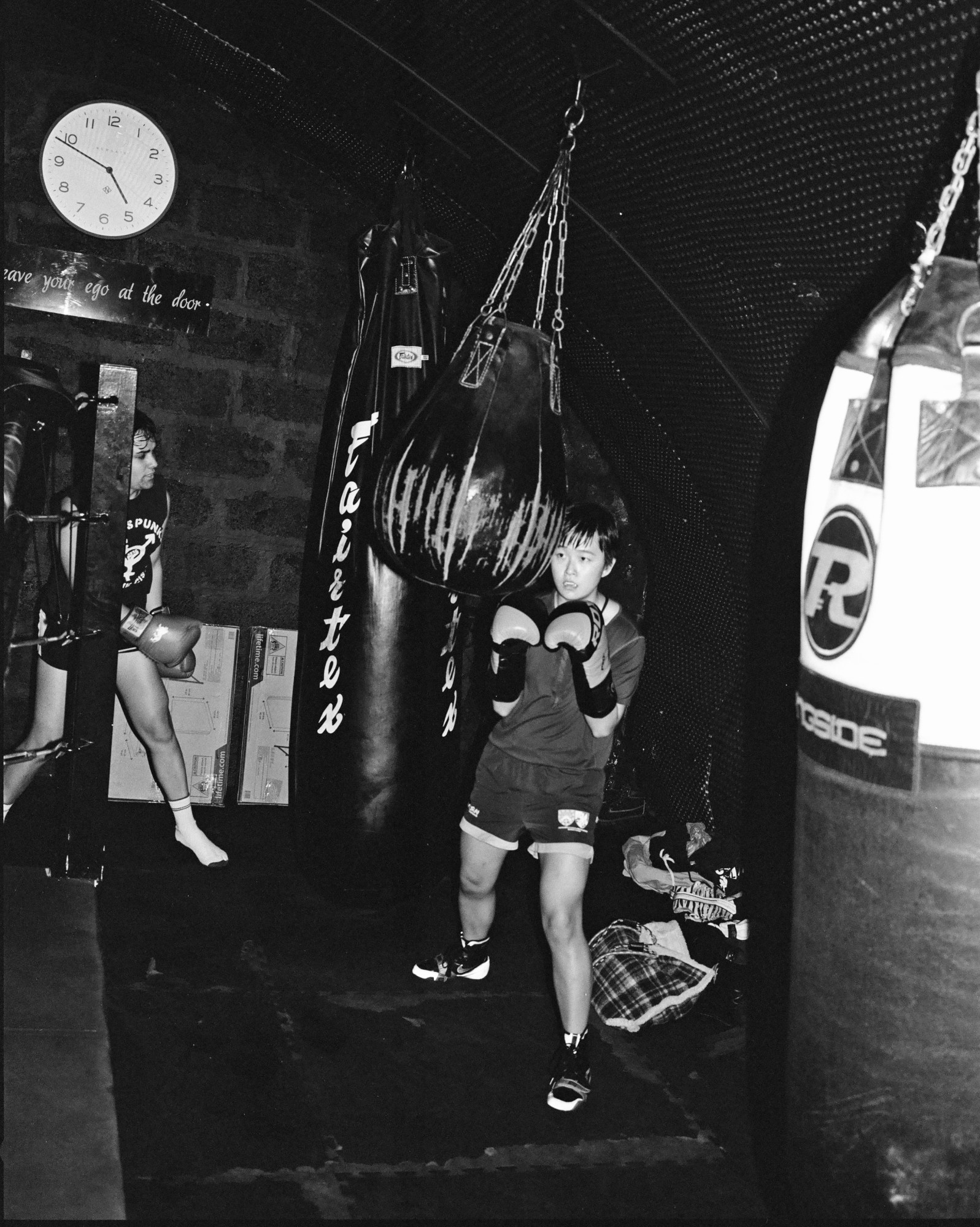

It isn’t often you find a martial arts gym filled exclusively with queer people. But, standing before me in the dark railway arches of Bethnal Green, a trans man and an amateur Muay Thai fighter are currently directing the movements of a group of LGBT+ participants and encouraging each of them to get their bodies into a ‘T’ position. “Yay, T!” someone shouts from behind. On the walls, generic inspirational quotes read ‘hit don’t get hit’, ‘respect all fear none’, ‘refuse to lose’, while slogan tees in the group say things like ‘fuck the cis-tem’ and ‘trans punks’.

I’m in attendance of a class hosted by non-profit community martial arts centre K.O Community Projects and Bender Defenders, a new street defence movement confronting rising hate crime against queer people (in their own words: “In London pre-pandemic we witnessed more attacks AND WE AIN’T GONNA STAND FOR IT after the pandemic”). Running weekly, these sessions offer more than just self-defence techniques, they’re also designed to provide a sense of catharsis for attendees who might often feel under attack in the outside world. As coach Luca Giraldi, 31, tells me: “This can be your space to release anything that happened to you.”

According to a report by Galop, an anti-queer violence charity, three in five LGBT+ people experiencing hate crimes want and need help, but only one in five are able to access any support. Worryingly, the number of incidents reported is increasing — UK Home Office figures show that the number of LGBT+ hate crimes reported has grown at twice the rate of other hate crime over the past two years. You can imagine the knock-on effect this has on depression and anxiety rates.

Cat Denby, 26, and Luca are both LGBT+ Boxing and Muay Thai coaches. They’re both queer and have suffered from poor mental health worsened by drugs and alcohol in the past. Cat and Luca have learnt to cope with these challenges with the help of martial arts. Now, they are creating a space to build a community beyond parties and club nights.

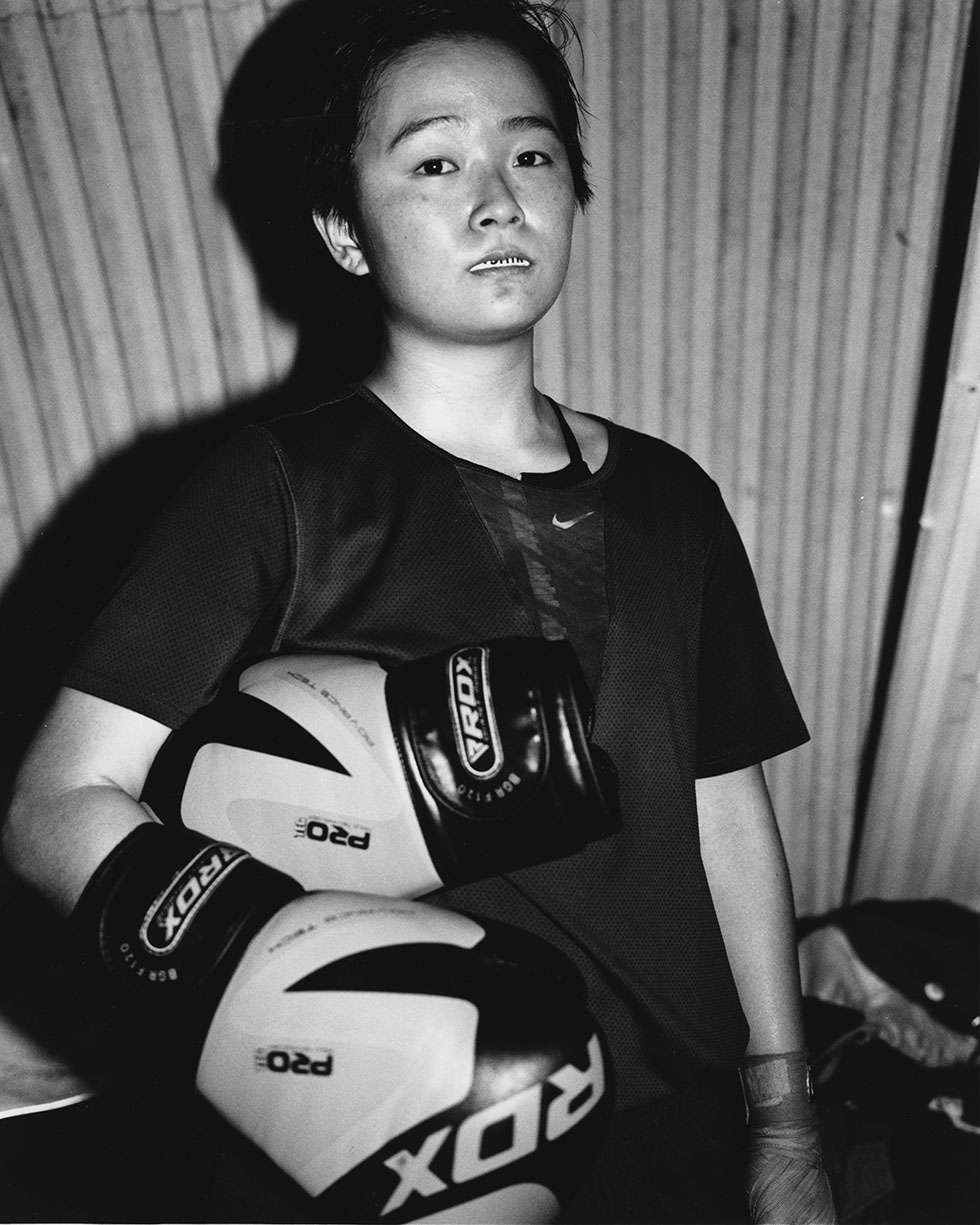

Anxious and stressed, once upon a time, Luca would pass a martial arts gym on his daily walk back from a demanding job. After a ‘fuck it’ moment and a few follow up classes, he was hooked. “I call it brutal mindfulness,” he says. “You can’t zone out; you have to be there for yourself; you have to be there for your partner. You have to remember combinations; you have to be quick. And you get to hit things. In those 90 minutes, I couldn’t think about anything else.”

Clarisse, 31, a regular who has been boxing for several years, advocates the sport similarly. “As queer people, we can often become detached from our bodies; they can become prisons,” she says. “Boxing can help you appreciate what your body can do for you and what it can take.” Despite being a solo sport, fighters need immense support in the ring and training. As Clarisse says, the community picks you back up when “you might cry because you feel like you can’t do it anymore.”

Luca and Clarisse’s words demonstrate how martial arts can be therapeutic for trauma. Alexandro Garcia Vargas captures this in his research into the psychological effects of martial arts training: fighters can re-enact violent events without feeling helpless, all while in a safe role-play scenario. They can become aggressors and defenders in a non-destructive way while fostering trust between partners and coaches. In this way, researchers have found that martial arts training can help people achieve “self-mastery.”

Despite the potential benefits of martial arts for queer people, as a community that disproportionately faces trauma, it is not a sport that has historically been accepting. As Luca and Cat acknowledge there aren’t many martial arts gyms that would make space for an LGBT+ class on their schedule. This can disrupt the psychological benefits of martial arts for queer people because attending a ‘regular’ class may remove the central tenet of safety. To go one-on-one with someone who is not queer, or not an ally, and who may not understand or respect boundaries could introduce a very real threat, and the role-play scenario might cease to feel like role-playing.

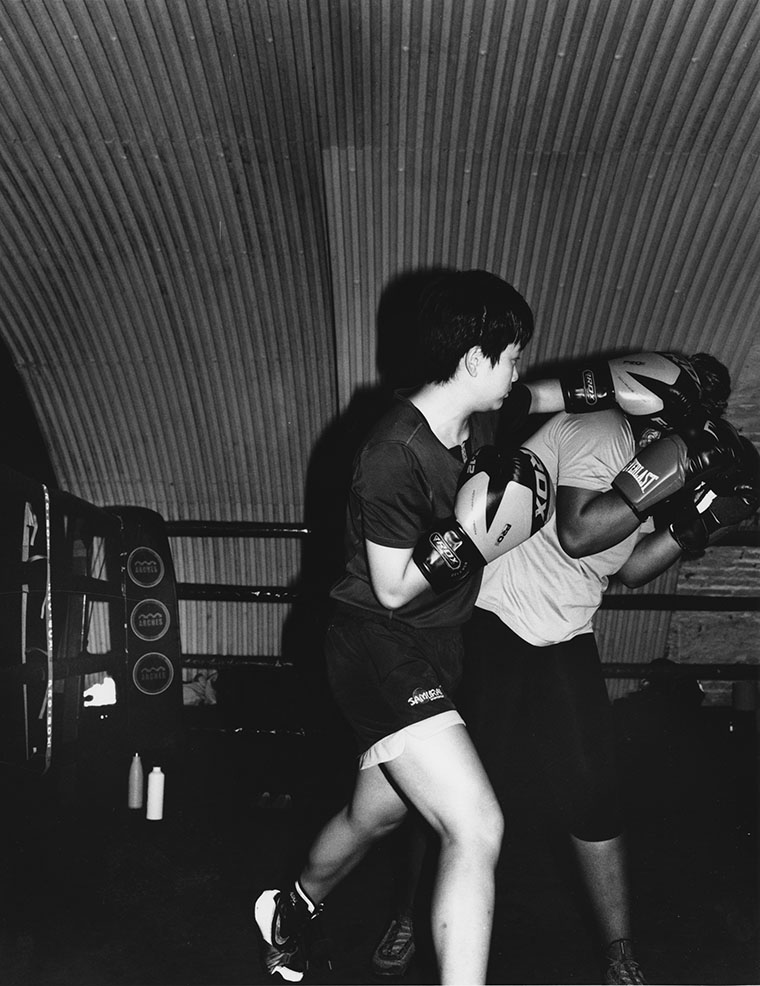

Cat and Luca are critical of martial arts spaces that set up LGBT+ classes without queer instructors. Unlike other queer boxing groups in the city, K.O’s class always begins with a round-the-room sharing of pronouns — safety, comfort, and acceptance must come first. As Luca puts it: “In order to provide something that is really unique, you have to have lived experience. You have to know what it’s like to be queer and to really need a safe space.” The team’s efforts for inclusivity are rewarded. Under the arches, there is a constant dialogue, not just between the coaches but between partners.

Inclusivity extends beyond queerness too. Cat and Luca recognise joining an exercise group can be intimidating if you’re less fit, and they want to bring in a wider scope of abilities. First time member Sally, 25, hit a wall after the warm-up. Cat clocked and changed the pace. Though the classes will push you, both coaches are sensitive to the wide range of abilities that attend and adjust their training accordingly.

Sid, 32, regularly trains in kickboxing. But at these classes, they find space for neuro-divergency that they don’t find in mainstream gyms. Here, if their top becomes a sensory overload, they will train in a sports bra, without worrying about the response from others. They are genderqueer at this class, but in a mainstream gym, they train as a woman.

By the end of the class, sweat is dripping from bodies and walls, the participants are tired, but the mood remains upbeat and light-hearted. Though the LGBT+ community is constantly forced to defend themselves outside these four walls, at 4pm every Saturday, politics is left at the door (with the TERFs). There is no agenda; they simply want queer people to feel safe.

KO Community Project’s LGBT+ boxing and Muay Thai classes run 4pm every Saturday at KO Combat Academy, Bethnal Green. All levels welcome, no experience needed, pay what you can afford, with a suggested donation of £5. More information can be found here.

Credits

Photography Jesse Glazzard